A Marriage Finely Tempered in the Misery of a Survival Drift

The story of MAURICE AND MARALYN BAILEY by Charles Douane from his excellent website WAVETRAIN

Aug 8/2025: There was a time when survival drift stories involving bluewater sailors were not unusual. From the early 1970s to the late 1980s, as bluewater cruising became increasingly popular, but the technology involved remained relatively primitive, we saw a steady trickle of them. These days, what with modern sat comms and global 406 EPIRB coverage, sailors forced to abandon boats offshore can expect to be rescued in just a few hours. Back in the “good old days,” however, it might take weeks or even months.

A new book by British journalist Sophie Elmhirst, published last year as Maurice and Maralyn in the UK and this year as A Marriage at Sea here in the US, retells the story of one of the longer ordeals—a 118-day drift endured by Maurice and Maralyn Bailey after their Golden Hind 31 was sunk by a sperm whale east of the Galapagos in 1973. Elmhirst is certainly not a sailor, but she does a good job nonetheless relating the nautical aspects of the story without insulting the intelligence of informed readers. But what she is most interested in is not the technicalities of how the Baileys survived, but rather how the experience affected their relationship.

The Baileys certainly did not fit the typical cruising-couple stereotype, wherein an eager husband lures a semi-reluctant mate into living afloat for a while. Maurice was leading a very isolated life prior to meeting Maralyn—“a pattern of detached bachelorhood,” he termed it—and was estranged from his family, though they lived close by. He had little to no self-confidence and socially was very awkward. Once they were married, it was Maralyn who eventually pushed the idea of selling the house, buying a boat, and sailing across oceans in it. This in spite of the fact that she knew little about sailing and couldn’t even swim.

They actually made a good team. Maralyn provided optimism and enthusiasm, while Maurice, a perfectionist at heart, focused on technical details. With Maurice obsessively following all the advice on offer in Eric Hiscock’s books, the couple lived very frugally for four long years while they prepared their little boat for sea. They fully appreciated all the pleasures of the cruising life once they finally cast off lines and got into it, and this process of shared sacrifice and just rewards only strengthened their bond.

The real test, of course, came when their boat sank from under them between Panama and the Galapagos. Maurice, having worked so meticulously to prepare the boat, at once saw its loss as a huge failure on his part. He was certain they were now doomed and plotted ways they might kill themselves to forestall their suffering. Maralyn, meanwhile, could not conceive of not surviving. She took the lead in plotting their subsistence existence, worked hard to keep them both mentally engaged, and insisted, even as they drifted helplessly across the eastern Pacific, on planning out the details of their next boat and voyage.

The Baileys christened their boat Auralyn, a mash-up of both their names. She was a plywood Golden Hind 31, launched in 1968

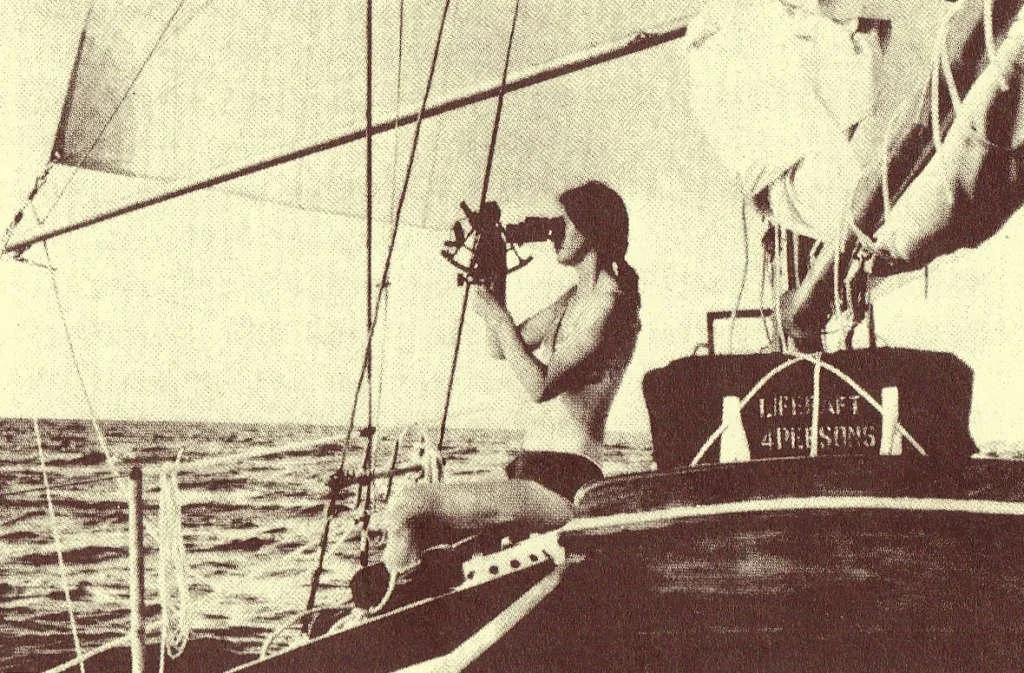

Maralyn takes a sextant shot while on passage

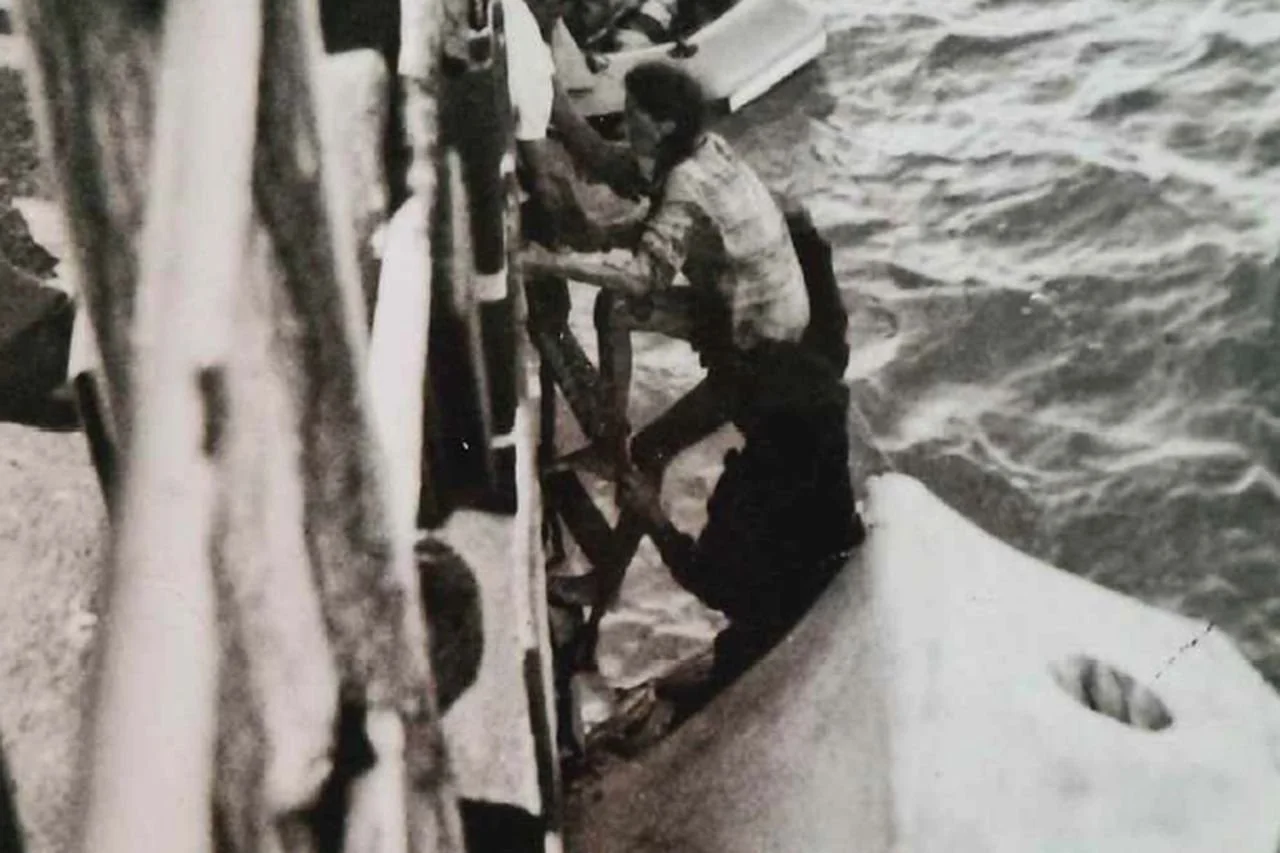

The liferaft and inflatable dinghy that sustained the Baileys during their survival drift, photographed soon after they were finally found by a South Korean fishing vessel, Weolmi 306, on June 30, 1973

Maralyn boards Weolmi

The Baileys and the South Korean crew who rescued them

Their 118-day drift took a circuitous route

In the end, Maurice effectively helped Maralyn find her strength, and Maralyn helped Maurice find reasons to keep on living. They fused together as one, in a very real sense, and when finally they were rescued and were immediately caught up in an awful maelstrom of global publicity, they came to regret that their special time together, lost in a natural wilderness with only each other for company, had come to an end. As such, their story serves as a sharp contrast to that of Bill and Simonne Butler, who spent 66 days adrift together in a liferaft in 1989. Where the Baileys stepped out of their raft with a stronger marriage, the Butlers, once out of theirs, immediately filed for divorce.

Throughout her book, Elmhirst documents the evolution of the Baileys’ relationship thoughtfully, empathically, and with an excellent eye for telling details. A good part of her narrative concerns what happened after the Baileys were rescued. Amazingly, as Maralyn always insisted they would, they did go to sea again in a new boat, with crew and this time to Patagonia, which is always a challenging cruising ground. My sole complaint with the book is that Elmhirst simply glances over this part of the story. She tells us only that the crew had many complaints about Maurice as skipper and leaves it at that. A more explicit explication would certainly be appreciated. Instead Elmhirst rushes on to tell us in some detail about the end of Maurice’s life, after he lost Maralyn to cancer in 2002, which is a sad story indeed.

Appropriately, I read this book (the UK edition, which I picked up on a recent trip to Ireland), while cruising about the Maine coast on Lunacy with wife Clare and Baxter the dog. Clare expressed some interest in the story, but—tellingly, perhaps—did not take up the book when I was done with it.

Sign up to WAVETRAIN to read more of Charlie’s excellent material