Finishing the year with a Rhyme

I know that rhyming poetry is considered “uncool” these days.

It’s probably bad rhyme that’s responsible for this shift in literary taste over the last century.

Ellen Roberts the well know editor said “The apparent ease of Dr. Seuss’s verse and his mad-cap nonsense have inspired so many untalented poets to mimic him that editors now cringe when they see a rhyming manuscript.”

But the distaste for rhyme goes back further than that. Early modernist poets like T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein reacted strongly against Victorian and Edwardian verse, where rhyme was often predictable and ornamental, and they argued that it encouraged poets to choose words for sound rather than for accuracy or emotional truth. Free verse came to stand for honesty, immediacy, and a closer fit between thought and language. In a culture that prizes authenticity and the conversational, rhyme can feel conspicuously artificial, a reminder that the poem is a man-made creation, rather than a moment overheard.

Because rhyme is so audible, weak or lazy rhyme is impossible to hide; sing-song rhythms and tidy couplets easily slide into the territory of nursery rhymes or greeting-card verse. As literary institutions increasingly favoured free verse, rhyme has become associated with the old-fashioned or the conservative. But when handled with real skill, rhyme can feel inevitable rather than clever, adding tension and resonance rather than resolving things too neatly. It can remind us that poetry is the art of craft, as well as feeling.

A Wanderer's Song

by

John Masefield

A wind's in the heart of me, a fire's in my heels,

I am tired of brick and stone and rumbling wagon-wheels;

I hunger for the sea's edge, the limit of the land,

Where the wild old Atlantic is shouting on the sand.

Oh I'll be going, leaving the noises of the street,

To where a lifting foresail-foot is yanking at the sheet;

To a windy, tossing anchorage where yawls and ketches ride,

Oh I'll be going, going, until I meet the tide.

And first I'll hear the sea-wind, the mewing of the gulls,

The clucking, sucking of the sea about the rusty hulls,

The songs at the capstan at the hooker warping out,

And then the heart of me'll know I'm there or thereabout.

Oh I am sick of brick and stone, the heart of me is sick,

For windy green, unquiet sea, the realm of Moby Dick;

And I'll be going, going, from the roaring of the wheels,

For a wind's in the heart of me, a fire's in my heels.

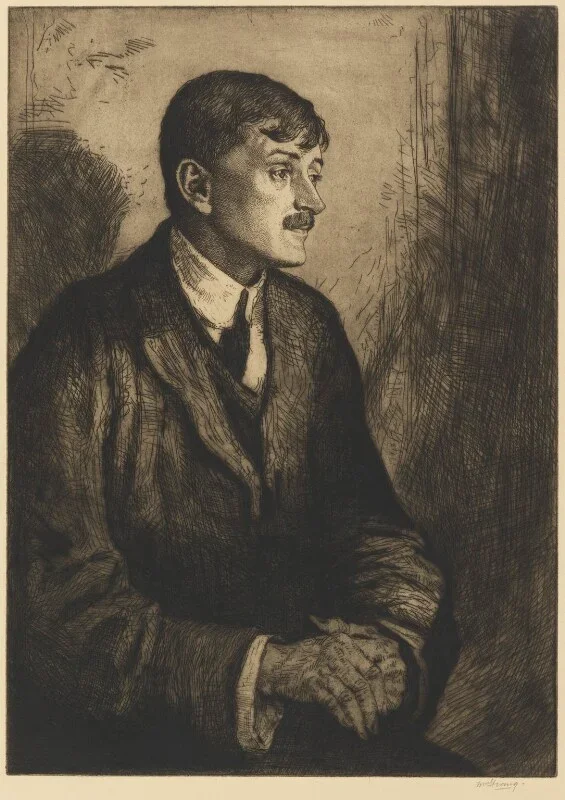

John Masefield wrote the poem above in 1902. He is famous for salt-stained poems like this, which get their authenticity from his lived experience. Orphaned young, he ran away to sea as a teenager, working as an apprentice aboard a ship bound for Cape Horn, where he endured brutal cold, exhausting labour, and stood long nights on watch—experiences that later surfaced in the muscular rhythms of poems like Sea Fever.

Years later, as Poet Laureate, he was teased by polite London society for his unrefined nautical themes; he replied that the sea had taught him more about truth, endurance, and beauty than any drawing room ever could.

The line “I must go down to the seas again” was not nostalgia—it was memory, and for Masefield, poetry was simply the act of telling the truth in the language he learned on a rolling deck… even if it did rhyme!