Sundance to Cairns - Part II

By Ian Marcovitch - Crowdy Head to Scarborough

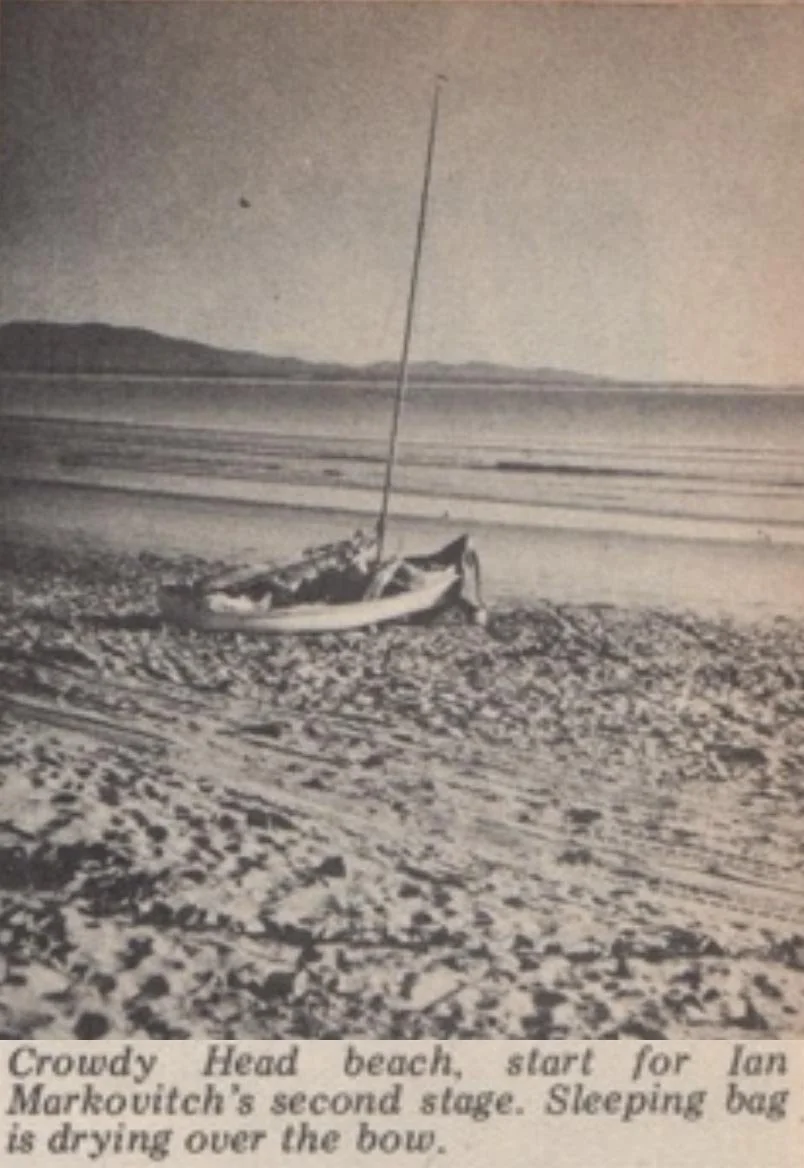

Crowdy Head is a long way from Sydney when you are sailing a small centreboard boat – alone. Reaching this far, just north of Taree, was a milestone for me. I knew now I could handle nearly everything and I was confident and ready to push on.

When I awoke on Crowdy Head Beach I found I was not alone. An old house nearby was surrounded by assorted board-toting cars and surfers looking for early swells were moving around. After breakfast I sailed smoothly off the beach in a light westerly as they, cursing, scurried about the coast looking for a swell. The wind swung round to the SW and I set the spinnaker. It was becoming a pattern, the spinnaker only scared the breeze away, or maybe signalled it to swing ahead.

The northerly breeze settled down and, with evenly split tacks, we made progress. The frustrations of my works to windward thus far had prompted me to rig the boat for optimum windward performance. To this end I’d raked the mast, tensioned the jib luff, and sheeted the jib about eight inches inboard.

We made way but the short seas were so steep half the boat would be caught in mid air and then come slamming down. I attempted to ease the motion by bearing away a little, but quickly realised the only smooth course would take me to Tasmania. Despite the slamming and pitching, we kept moving north. All this time I was out on the straps and, with the sunburn and chafing, my feet were complaining.

Darkness came quickly. We pitched and lurched to windward with riots of phosphorescence boiling about us. Thankfully encroaching waters quickly disappeared through the self-bailer.

When we reached the light beacon we’d been working toward, there was no beach tucked away nearby, so it was on to the glow of Port Macquarie. Strange as it may seem, I found it hard to navigate into harbours at night. The bright lights blot out the features of the coast you are looking for. This was my problem at Port Macquarie, and after poking around waiting for the moon to rise it was the incoming tide which eventually took a hand and swirled us in. Once ashore I watched the Easter festivities, and treated myself to a chicken dinner.

I was still on the beach long after returning from Easter Sunday service because every person I asked reported different weather forecasts.

Well into the morning, having taken two youngsters who had been fishing nearby for a spin, I decided to sail. The wind was SE and Sundance revelled in her off-wind freedom. My big consolation of the day was to see MH67, a trim yacht twice our length, beating southward, slamming up and down just as relentlessly as we had done yesterday.

Monday was one of my best runs so far — some 60 miles from Hat Head to Coffs Harbour. Once the breeze hauled down from the SE the spinnaker went up, and my thoughts were accompanied melodiously by the slurping music of the self bailer.

Coming abreast of Nambucca Heads with the sun still high, all thoughts of calling in were blown away as I grappled with the spinnaker.

The breeze was piping up. White heads frothed sporadically. The bursts of planing were more determined, the boat straining like an ensnared beast, with water spuming from her gunwales. We rushed along the coast. It was wonderful. The best rides are always accompanied by a fear-struck intestinal strangulation.

That kite had to come down. The wind was too strong. “George, hold the tiller!” I might have said. Why is it just as the foot of the kite is in reach the boat threatens to capsize, and as you scramble to gather it in the kite flaps away?

Sometimes old “George’’ would suddenly let the tiller go, adding to the confusion of whipping lines, flapping, and rolling lurches. The kite this time flew well out to leeward, tugging to toss us over. But a quick catching of the sheet just as I released the halyard saved the day. We stayed moderately upright.

The close reach to Coffs Harbour kept me out on the straps. The shallow waters beneath threw a messy chop but occasionally we found a swell going our way. Long socks and shoes protected my feet, and I was really enjoying the toss and tumble game with which the day was ending. I felt quite triumphant as we eased off to broad-reach into Coffs Harbour.

There was a possibility of showers during the night, and so I rigged one side of the “space blaket” along the gunwale then lay my sleeping bag on the other half of the “blanket” which was drawn on the ground towards the keel. In this way the boat was used as the primary shelter, with the blanket keeping off light rain.

The seas north from Coffs Harbor, right up the coast, are far more choppy than those southwards. A few days later we were beating against a NE and the chop was so steep a couple of times the stern was in one wave and the bow ploughed into the next, sending sheets of water over the length of the boat. At times like this I couldn't help but admire the boat’s design; with head winds, steep chop, and single-handed, we still made ground to windward at sufficient speed for the bailer to stem the risingt tide at my feet.

This beat to windward was the culmination of a very long day. Early in the morning at Yamba a heavy burst of wind and rain had literally caught me napping, and, after a futile attempt to dry my sleeping bag over a fire, I decided to get moving. So, in the company of a pair of porpoises, Sundance and I turned north from the Clarence River. We had a few hours to sunrise, and when, late that afternoon, we eased off to plane on the swells running through the breakwater into Ballina a lot of overtime had been chalked up. However this overtime had not resulted in many miles, and I was a little disappointed.

After buying provisions in Ballina and sending off letters, I was all prepared to curl up under a dinghy on the beach. However on arriving back at Sundance I was shanghaied by Jeff whom I’d talked to when I first landed. He’d come down to invite me back to his caravan for the evening.

Over copious coffee cups, Jeff, his wife Noelene and I talked about our sailing experiences, and it was quite late by the time we turned in. Next morning I was treated to my first civilised breakfast in many days. Jeff and Noelene were heading back to Belmont as I prepared to set off.

It’s amazing what a good night’s sleep can do, especially if it is topped with a filling breakfast. The wind was blowing freshly from the northeast didn’t worry me as I rigged up, though I did set the smaller jib. So long as the weather didn’t look like getting any worse I felt that we should get to Byron Bay or perhaps even Brunswick Heads, if the winds changed. But I set off tentatively, ready to turn back if the seas should seem worse than it looked from the shelter of the river.

We lifted the incoming swells as we moved away from the bar. The seas outside looked rough. Then from wall to wall a swell heaved up and, higher, higher, it broke. Foolishly I figured it would be possible to outrun the spinning round pressed Sundance to accelerate before it. Too late! I made an abrupt dive down the face of the breaker yet under.

The water was flat as I surfaced. I swam to the upturned hull, and having clambered on to it I surveyed the scene.

My biggest worry was the south wall of the breakwater. We were still in the breakwater area and it looked as though we’d be carried on to it. An ebb tide carried us clear. No other waves broke, and once clear I struggled to right the boat. Because the mast was broken it couldn’t provide the buoyancy necessary to bring the boat up to the horizontal position. Consequently the great stability of the hull made it impossible to re-capsize it by my weight alone.

With the jib sheet in one hand, and spinnaker sheet in the other from the port side, I braced my feet on the starboard gunwale and stood out trapeze style using the sheet as my wire. This alone didn’t provide sufficient leverage to right the boat, so with each passing wave lifting the port side slightly, I bounced my weight to accentuate the effect. It was apparent this was wasn’t sufficient, so I conserved my energy until I saw the wind too added force when the gunwale lifted. The combination of my levered weight bouncing when a large wave arrived, and the sudden strong wind gust, worked, and I walked up the hull as she lifted, and flopped right way up.

What a mess! I set about clearing up and trying down. We’d drifted some distance down the coast, and I had to decide whether to try to go in to the beach, or head down the coast toward Evans Head or Yamba. The beach was out — look at what a wave had already done. South it was to be. To my chagrin the centreboard which had been there after the capsize was now gone. To improve steerage I put one of my hatch covers down the empty casing, and then eating dry biscuits, steered for Evans Head.

At this point a large trawler came bearing down on us from Ballina. We were to be rescued. All the gear now had to be untied and thrown aboard the trawler. A number of times it looked as if rescue was worse than my predicament. The trawler alongside pounded with its heavy gunwales slamming down at Sundance, bobbing like a bottle near rocks.

A sling soon had Sundance up on deck, and tied down for the return to Ballina. I hadn’t been worried by the incident, taking it rather as a typical sailing mishap. But now that I’d been “rescued” I was expecting a dressing down from the crew. It didn’t come; instead I was told the stories of others far less fortunate who had lost everything on the Ballina Bar.

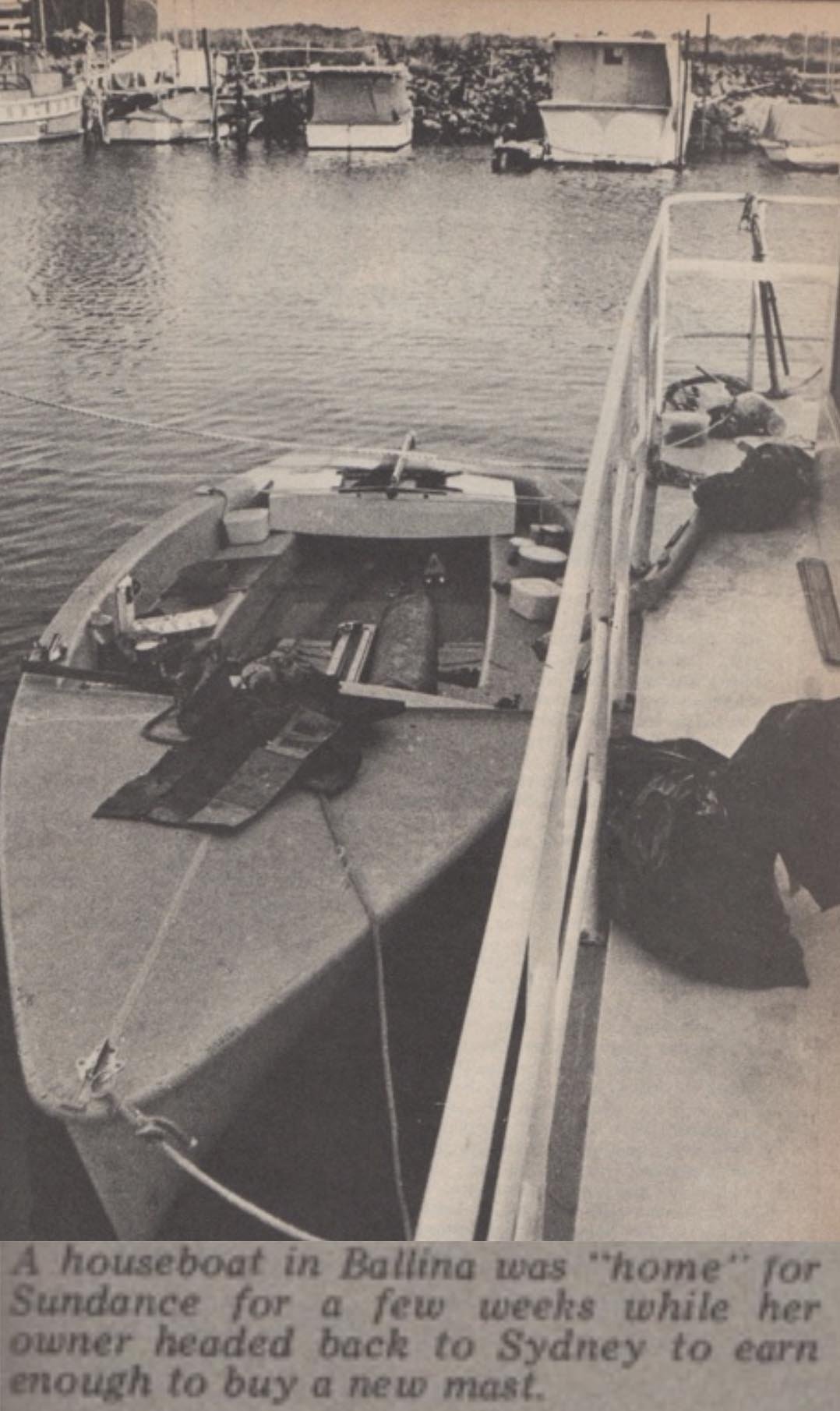

Back in port I cleared up everything, and dismantled the mast. One Jim Cox, who’d come on the trawler in search, offered me the use of his houseboat to store my things. For this I was very grateful as it looked like being a couple of weeks before I could return from Sydney with a new mast and centreboard. It would take me that long to earn the extra money. The afternoon sun soon dried the wet gear, and I stored it on Jim’s houseboat for my return.

After a night’s sleep on board, I left on Saturday morning to hitch to Sydney.

The trip back was a far more dangerous undertaking than sailing alone up the coast. The driver of one car found that 100 miles an hour (160.9 km) was a bit fast when we began sliding across the expressway. Then in Sydney I almost killed myself on my push-bike. I quickly scraped a few dollars together and had the new mast and centreboard sent to Ballina. Now for the “safety” of the sea.

Another hitch-hike and I returned to Ballina on May 10. The next few days I spent repairing the sail and fitting out the new mast. I was disappointed to find one of the hound fittings on the new mast was secured by only a single pop rivet instead of two. I wasted a morning to secure a quarter inch (6.35 mm) diam pop rivet, and ended up temporarily fitting a self locking steel bolt. This I coated with vaseline hoping it would not corrode before I could fit a pop rivet in Brisbane.

I said “thanks” to Jim and “good-bye”, and after church that Sunday I again set out from Ballina. This time I felt quite on edge as I approached the breakwater, and with the sea looking frothy outside I was almost relieved when one of the hiking straps gave way. By the time I’d repaired it I felt tired, and the sea didn’t look so rough.

We cleared the breakwater safely, and in the brisk southerly I was relieved to have company. A large trawler and a small yacht were sailing past, and I set out to catch them. The wind was quite strong and as the seaway was square before it I decided to tack down wind rather than run wing-a-wing in the irregular seas. I didn’t catch the trawler but the smaller yacht I left far behind.

The wind increased and white caps laughed at me, and nearby a steeper swell would collapse into foam. Sundance ploughed into troughs, bows only inches clear, only to lift smoothly and plane. If I hadn’t so recently pitch-poled I would have enjoyed myself.

To add to the confusion of the sea a school of dolphins picked me as their play mate. They took great delight in showing me how much sleeker they were by cutting across in front of us, or darting past sometimes with only inches to spare.

After all this—when I found I had only just cleared a couple of submerged rocks off Byron Head—I barely twitched.

Byron Bay is beautiful. As yet it is uncluttered by the degradations of civilisation. It so happened both in the evening and early morning the fishermen netted their catch where Sundance was beached. For my efforts in lending a hand on the net, I had fish for tea and breakfast. They were quite intrigued by my voyage, and wished me the best of luck. But they also warned me about the Tweed River entrance, “Almost as bad as Ballina.”

The next day was both confusing and annoying. The wind swung in a complete circle through the day, going from westerly in the morning through the south to the east and north until at Tweed Heads it was again blowing from the west. In retrospect this doesn’t sound so bad, but at the time I didn’t think to anticipate a wind change so much lest I end up in Fiji on the southeast waiting for the swing to northeast.

I had some difficulty fixing my position on the chart, and this led me to steer wide of the reefs south of Tweed Heads when I was not yet there. As I came further inshore up the coast I then ran into the reefs I had tried to avoid. It isn’t nice finding yourself in an area where lunging waters erupt over unseen rocks. The sun picked this moment to dip into a light squall. I wasn’t very happy as I picked my way back out to sea and past the reefs. As we set course northward I saw the gathering gloom I thought, “This is it—an all night effort.”

However, a couple of hours beating to windward brought up the red and green beacons of a channel. With my heart in my mouth we moved around, lifting to the invisible swells that rushed in to smash on the breakwater walls. The tide was running in and whether by luck or timing we soon found ourselves sailing smoothly up the channel. On and on we went—there was nowhere to pull up. I saw a spot and with torch beam flashing like a blind man’s cane, I tried to get us in. Crunch! We ran into a submerged oyster lease.

Clear of the oysters I noticed the depth of water in the boat was increasing. Thinking the bailer might be open I tried to retract it. To my horror, I saw in the torch light a mangled piece of stainless steel, useless amid the gushing water.

Eventually I found a spot near a launching ramp. Thus I landed at Tweed Heads. I talked with a fisherman about the trip and he finished the conversation: “Take this extra flask of water, you can’t have too much”. I thanked him.

In the morning I removed the self bailer and bolted a piece of plastic ice-cream container over the aperture in the hull. Not wanting to miss the top of the tide I scurried off down the river to the bar—but there was no trouble.

It was strange to sail past the towering buildings of Surfers Paradise, picking my way through the flotilla of holiday fishermen. Quietly tacking against the wind past all this rumbustious holiday world, I felt like an observer from Mars.

Having planned to traverse the Southport Bar, and knowing its reputation, I approached warily. The tide was ebbing madly, and rapids and waves were everywhere with the water not more than three feet deep. The situation couldn’t have been overcome by anything larger than Sundance. After sailing back and forth in front of the bar, I found a smooth run on the southern side where the sea swell wasn’t breaking. I took Sundance through this opening to the beach. I then walked her along the shore around the edge of the Bar till we were safely in the Broadwater.

Wednesday, May 15, was quite a day. From Broadwater it seemed my best bet was to follow the eastern channel. With a fair southerly behind I had hopes of reaching Scarborough at the other end of Moreton Bay.

The wind picked up and we were chewing out the miles. Used to the open sea I didn’t like the direction of a channel dictating me the time to jibe.

Consequently one ill-timed jibe left me in the drink. No problem, except, not having a self-bailer meant a lot of hand bailing.

Here in the wilds of the channels I got quite a surprise when, just after rounding a small island I saw a fellow Corsair and a Vagabond beached. We couldn’t sail past, and were waved in by their crews.

“Hi! Where are you going?” they asked.

“I hope to get to Scarborough,” I replied.

“That’s a long way to go — especially by yourself. Where have you come from?” they asked.

“Sydney,” I said, trying to sound as off-hand as possible.

“Tell us another one,” they chortled.

“Well, would you believe I stopped a few times between here and there?” I said.

“You’ll have to tell us about it — and in a Corsair too! Anyhow, come and ’ave a cuppa,” said Jim Grant, the man whose family and friends I had sailed into.

Jim ended up giving me a good map of Moreton Bay, his friends lent cast of beer and some biscuits. It was more than hot coffee which left a warm glow in me as I parted from new friends to face the freshening southerly.

I don’t like running square in fresh conditions, but in a place like Moreton Bay it’s better to run square than get fouled up on a mud bank. Despite my trying to set safe courses in the channels, we often found ourselves ploughing ruts across hidden mud banks.

The next two days I spent with friends at Scarborough while I repaired the venturi bailer and scouted round for a pop rivet for the mast. My search was in vain and so I used a quarter inch stainless bolt pulled from inside the mast instead.

The time was also used to lay in information on what I considered the second half of the trip. As a New South Welshman, half the battle seemed to have been fought in reaching the border — now all I had to do was sail to Cairns.

Look out for the third and final part of this epic adventure in next week’s SWS