Striving for Truth in a Post Truth World

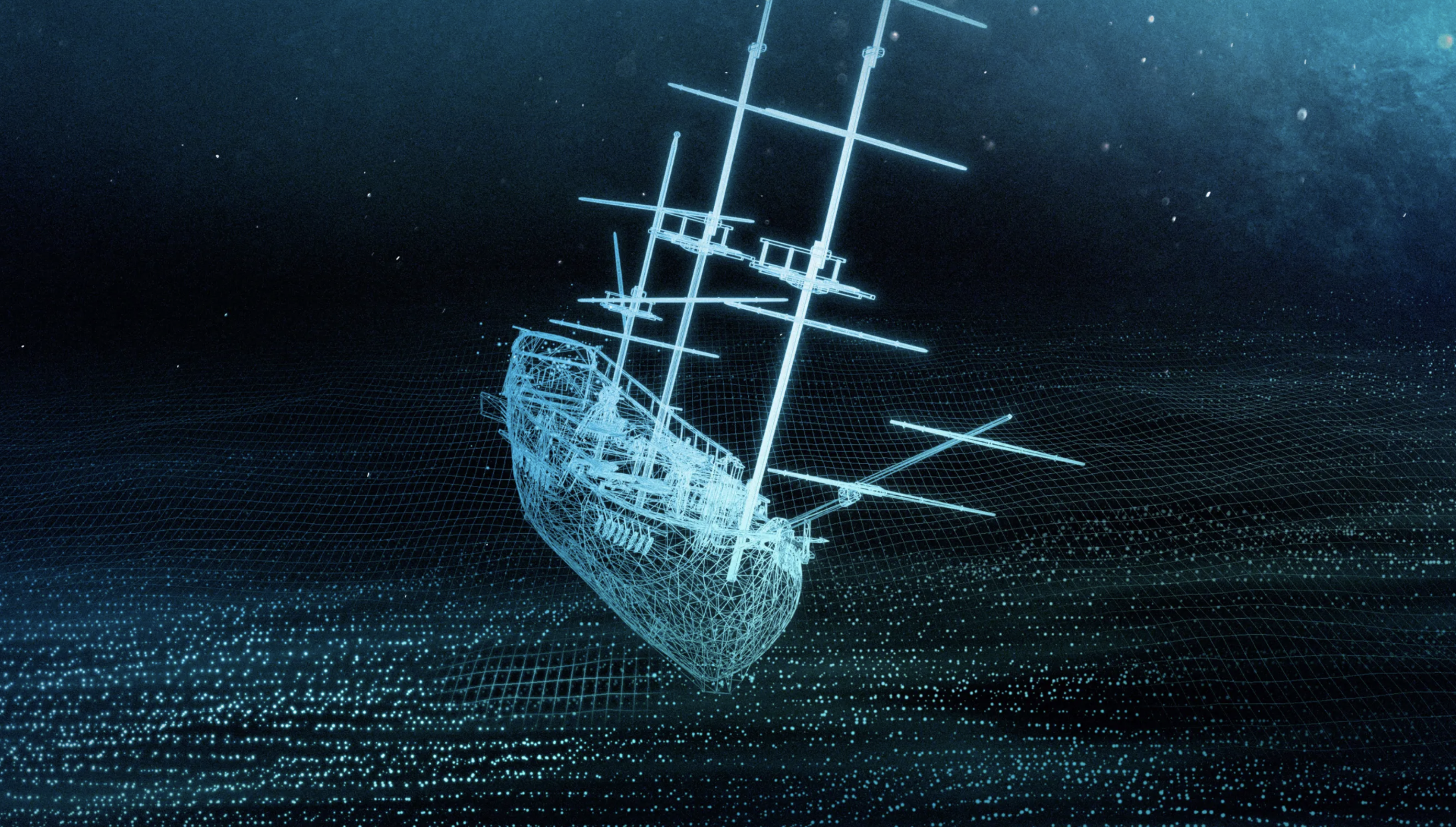

A digital model from a photogramic survey of the ENDEAVOUR.. CREDIT:DEEP DIVE

A few weeks ago SWS published an article rejoicing in the claim that Cook’s ENDEAVOUR had been found. Like many in Australia, we may have gone a bit too early. As believers in science and solid research before sensational media releases we thought it was important to rebublish this piece which appeared in this weeks AGE newspaper.

Shipwreck site is new battleground over truth about Captain Cook’s Endeavour

FEBRUARY 21, 2022

Kathy Abbass was furious. For 22 years, the American researcher had toiled over the fate of one of the most important and contentious ships in history: the HMB Endeavour, which British explorer James Cook sailed to Australia in 1770.

It had been a labour of love for Abbass since 1999, ever since she uncovered archival information at London’s Public Records Office suggesting that the Endeavour’s remains lay in waters in the Rhode Island harbour city of Newport, the sailing capital of the United States.

But just as her team at the Rhode Island Marine Archeologist Project were getting closer to solving the mystery once and for all, the group’s research partner, the Australian National Maritime Museum, conducted a press conference on February 3 to announce to the world that they were sure the wreck was the iconic Endeavour.

A pre-visualisational digital model of Lieutenant James Cook’s vessel the ENDEAVOUR. CREDIT:DEEP DIVE

Abbass, the lead researcher for the study had been given a copy of the museum’s report days ahead of the announcement, but still couldn’t believe what she saw as audacity. Two weeks after she made global headlines by accusing her counterparts of acting on “Australian emotions and politics” rather than science, she and her allies in Rhode Island remain unimpressed by the museum’s conduct.

“We’re totally thrilled to have the participation of our Australian mates, but there are ethical protocols within the field of archaeology that everyone should respect,”

said Joe McNamara, a Democrat in the Rhode Island House of Representatives who is also a project volunteer hunting for another significant ship in the American Revolution: the HMS Gaspee.

Rhode Island House of Representatives Democrat Joe McNamara: “We’re totally thrilled to have the participation of our Australian mates, but there are ethical protocols.”CREDIT:FAITH DUGAN

“I realise the excitement that everyone is feeling, but when that announcement is made, you want it based on science, backed up, and indisputable. With Dr Abbass, that is the criteria.”

Abbass is still not talking publicly about the maritime stoush, opting to spend her days in her lab in the Rhode Island town of Bristol conducting a comprehensive data-analysis, which is expected to continue until mid-April.

Kathy Abbass, Director of the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project.CREDIT:JENNY MAGEE

But the final report, due to be released before June after it’s reviewed by Rhode Island’s Historical Preservation Commission, will address the researcher’s claim that the Australia’s National Maritime Museum breached its contract with the Rhode Island project team.

The Rhode Island Marine Archeologist Project argues it is the study’s lead authority and therefore has the intellectual property rights for all the data – a claim that the Australian museum strongly denies.

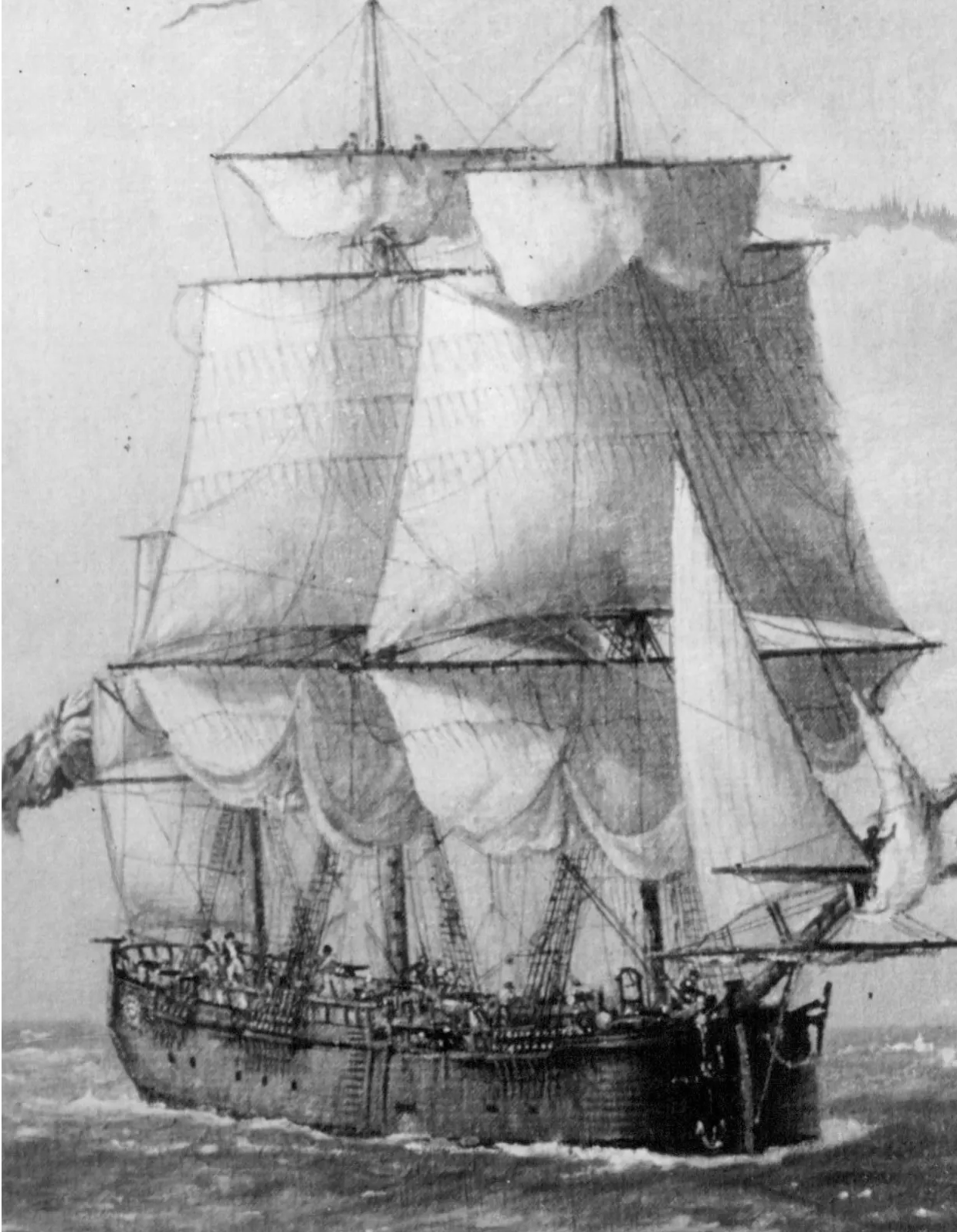

A painting of HMB ENDEAVOUR by John Alcott.

And despite the Australian National Maritime Museum’s insistence that the ship had been found, documents also suggest a series of “cautions” remain. Among them is the “possibility that modern intrusions have damaged or disturbed the sites” making indisputable identification a challenge.

Scavengers have carried off artefacts that “may mean that particularly important diagnostic pieces that could identify a shipwreck are now missing”. The Australian National Maritime Museum was forced to amend its latest report after including the exact site of the shipwreck on a map, which Rhode Island authorities warned could lead to more looting.

The wrecks on the seabed of Newport’s Outer Harbour in the 18th century are not of interest only to Australian historians. Some of the vessels played a part in the American Revolution.

“Given the subtle nature of the 18th-century sites and the difficulty to find them, RIMAP can not yet say with certainty that it has found all of the transports that still exist in Newport’s Outer Harbor,” the project has warned in an online document.

Several shipwrecks lie off the shore of Newport Harbour, many of which played a part in the American Revolution. CREDIT:FAITH DUGAN

So was the Australian museum’s announcement premature, as some in the US suggest? Has there been a breach of contract, as Abbass has publicly claimed, and if so what happens next? And if the final resting place of Captain Cook’s ship is off the coast of Rhode Island, who gets to claim it?

On the snow-capped north side of Goat Island – far removed from the historic mansions, boutique shops and cobblestone pavements that line Newport streets – there’s a nondescript sign overlooking the water.

“Off This Shore Lies Capt. Cook’s Endeavour Bark,” it says.

The sign was erected two years ago by Gurney’s Resort, the upmarket hotel on the island that has become a hotspot for weddings, long lunches and quiet getaways.

The only marker for the site where the ship identified as the ENDEAVOUR lies. CREDIT:FAITH DUGAN

A few hundred meters away, just in front of the picturesque Newport Bridge, a series of “No Anchor-No Dive” buoys mark the study area that is now at the centre of an international maritime spat.

If it turns out the Endeavour is resting off this shoreline, it’s unlikely that what’s left of the vessel will ever return to Australia again.

Only 15 per cent of the ship remains and it belongs to the state of Rhode Island, its management overseen by the Historic Preservation Commission.

It will stay in Newport’s outer harbour, yet another drawcard for a town that has attracted many wealthy tourists, from president Dwight Eisenhower to actor Johnny Depp.

It was in these waters in 1983 that another famous vessel, Australia II, changed the sailing world forever by defeating the US in the America’s Cup for the first time in 132 years, ending the longest winning streak in sporting history.

AUSTRALIA II wrested the America’s Cup from the US in Newport Harbour in 1983. CREDIT:AP

“The most spectacular boats in the world come here,” said Newport Harbour Master Stephen Land, whose job it is to direct daily boating in the area.

“There aren’t any out there now because of the weather, but in summer, you can’t even see across the harbour – there are so many of them. I think it’ll be really great if it turns out we have the Endeavour as well.”

Some locals, such as James Poutney, a waiter from Providence, said he had never heard of the Endeavour. Others, such as Gurney’s Resort general manager David Smiley, said he hoped confirmation of the wreckage would boost post-pandemic tourism.

“Boy, let’s hope it’s the ENDEAVOUR, as that would be a great thing for Newport to talk about and promote, so I’m keeping my fingers crossed,” he said.

Others are cautiously optimistic, noting that it is not the first time scientists believed they had finally found the final resting place of Captain Cook’s ship. Among them is Ruth Taylor, the executive director of the Newport Historical Society. In her office, Taylor points to a frame, featuring a fragment of the Endeavour’s sternpost – or so it was thought.

Ruth Taylor keeps the misidentified fragment of wood that travelled to space as a reminder to not jump to conclusions. CREDIT:FAITH DUGAN

The tiny piece of wood was carried aboard the Apollo 15 spacecraft, also named the Endeavour, during its first moon shot in 1971. It was later discovered that the fragment had been misidentified.

Taylor said she kept the frame on her wall for years as a reminder never to jump to conclusions. Interested observers also know there’s a fair way to go: as the Australian National Maritime Museum’s report this month pointed out, five out of seven research criteria to positively identify the Endeavour have been given the green light, but one more dive expedition might be needed to positively identify some pieces of timber wreckage.

This year’s field work will “clinch the deal”, Taylor hopes, but she also notes that Cook’s ship has had “a mixed life” – a symbol of adventure, but also of colonisation and subjugation.

“Like all colonial efforts, it started something that could be described as awful and, when it came back here, it was a prison ship for American prisoners of war, at least for a while,” she said.

Operator: Royal Navy

Builder: Thomas Fishburn, Whitby

Launched: June 1764

Acquired: 28 March 1768 as Earl of Pembroke

Commissioned: 26 May 1768

Decommissioned: September 1774

Out of service: March 1775, sold

Renamed: Lord Sandwich, February 1776

Homeport: Plymouth, United Kingdom

Fate: Scuttled, Newport, Rhode Island, 1778

Class and type: Bark

Tons: 366

Length: 97 ft 8 in (29.77 m)

Beam: 29 ft 2 in (8.89 m)

Depth of hold: 11 ft 4 in (3.45 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship 3321 square yards (2777 m2) of sail

Speed: 7 to 8 knots (13 to 15 km/h) maximum

Boats & landing craft carried: Yawl, pinnace, longboat, two skiffs

Complement: 94, comprising: 71 ship's company 12 marines 11 civilians

The Navy purchased her in 1768 for a scientific mission to the Pacific Ocean

Departed Plymouth in August 1768, rounded Cape Horn and reached Tahiti in 1769.

She then sailed to the islands of Huahine, Bora Bora, and Raiatea west of Tahiti. In September 1769, she anchored off New Zealand.

April 1770 Endeavour became the first European ship to reach the east coast of Australia, with Cook going ashore at Botany Bay.

She was finally scuttled in a blockade of Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island in 1778.

“So there are parts of the history that are dark and like many historical events, it starts to feel a little disingenuous to just be celebratory about them. We just kind of have to recognise them.”

After Cook sailed the Endeavour into Dover on July 12, 1771, at the end of his famous two-year voyage of discovery, the British Navy sold the ship to a private owner, who renamed her the Lord Sandwich and sent her to transport British troops and German mercenaries during the American Revolution.

The ship was one of 13 vessels deliberately scuttled by the British in Newport Harbour in August 1778 to create a blockade that would thwart the French fleet.

Two centuries later, the Australian National Maritime Museum started working with the Rhode Island Museum Archeological Project to investigate a two square mile area where they believed the vessel sank.

It was a laborious task. Five archeological expeditions between 1999 and 2004 failed to gather enough evidence to identify the wreck site.

A breakthrough came in 2016, when Australian National Maritime Museum’s Nigel Erskine discovered archival evidence that substantially narrowed the location within the harbour and limited the study area to just five of the 13 transports sunk in 1778.

After several more years of mapping, documenting and excavation, on February 3 this year, the museum decided to announce, on a “preponderance of evidence approach”, that the final resting place of Cook’s Endeavour had been found.

These included a length of measurement from the ship that corresponded exactly with the Endeavour; timber sizes consistent with the make of the ship; and scuttling holes along the line of the keel.

Within an hour of the museum’s announcement, an outraged Abbass issued her angry rebuke, labelling the revelation as reckless, premature, and a “breach of contract”.

”What we see on the shipwreck site under study is consistent with what might be expected of the Endeavour, but there has been no indisputable data found to prove the site is that iconic vessel, and there are many unanswered questions that could overturn such an identification,” she said.

The Australian National Maritime Museum managing archeologist Kieran Hosty puts it down to a difference of opinion. He admits the two groups have had a contract in place since 1999, but it expired in October “and no matter what RIMAP and Dr Abbass think, the information is not owned by them – it’s owned by the state of Rhode Island”.

“She believes that the only way of identifying the site is through a positive artifact,” he said. “But because of the nature of the site, the chance of finding that is extremely remote. The only way we can identify the site is to look at the archaeology of the ship’s hull, which is what we’ve done.

“We’d just really love to see the site protected and interpreted in some way, and we’re very open to conversations with Dr Abbass – even if she disagrees with our findings.”