The Kauri Gum Diggers

By Malcolm Lambe

Ever heard of Kauri gum? No, me neither — until I stumbled across an old photo of a couple of kauri gum diggers living in a boat – complete with a tin and mud fireplace/oven in the stern. What's a “kauri-digger” I thought.

Houhora Harbour- Circa 1910-18

The story of kauri gum is a uniquely New Zealand one — a tale of golden resin, human grit, and the promise (or illusion) of fortune buried in the mud or in some cases – up a tree. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, kauri gum was a vital component of New Zealand’s export economy, rivalling even the lucrative wool industry.

The Origins of Kauri Gum

In November 1769, the great British navigator James Cook first found what he thought was mangrove gum at Mercury Bay in the Coromandel. He was wrong — as missionary and “flogging parson” Samuel Marsden later recorded, the resin came from the mighty kauri tree. By 1842, explorer Charles Heaphy was noting its use in varnish, and before long, gum from New Zealand’s northern forests was being shipped to London to make marine glue, fire-kindlers, linoleum and, most profitably, varnish. Its still used in varnish today. They say violins and other musical instruments painted with kauri gum varnish have a particularly good timbre.

By the mid-1840s, a full-fledged export industry was under way. Kauri gum, prized for its clarity and workability, was soon selling to manufacturers across Britain and America. Māori and European settlers alike began scouring the Northland soils for this strange, glistening treasure.

Māori Uses and Traditions

Long before Europeans saw profit in it, Māori called the resin kāpia and found countless uses. Fresh gum from trees was chewed like toffee; older gum was softened in water and mixed with the milk of pūwhā (sow-thistle). Its easy flammability made it ideal for torches and fire-starters. Burnt kauri gum also produced a fine black soot used as pigment for moko — the intricate facial tattoos of high rank. The soot was also used to close wounds.

How the Gum Forms

Kauri trees (Agathis australis) — giants that can live for over a thousand years — constantly ooze resin from wounds, cracks, and fallen limbs. It’s their way of sealing damage. Over centuries, this resin drips down and collects around the roots and forest floor, gradually hardening. When ancient kauri forests died, their remains were swallowed by swamps and sands, preserving the gum like buried treasure.

In New Zealand, kauri forests once stretched across the northern half of the North Island — from the Coromandel to the Aupouri Peninsula. Successive forests rose and fell over millennia, leaving layers of resin underground.

Captain Cook once dubbed the Aupouri the “desart (sic) shore,” a fair call given its rolling dunes and windswept emptiness. Yet beneath that barren surface lies proof that the land was once rich with life. Successive kauri forests once covered it, each growing, dying, and sinking beneath layers of peat, pumice, and sandstone. The most recent of these, carbon-dated to around 3,000 years ago, now lies buried in a tangle of swamp — a puzzle, since living kauri can’t abide wet feet. Even today, at low tide in Houhora Harbour, the stumps of those ancient trees still out from the channel.

Where It Was Found

The only true kauri gumfields in the world are found north of a line running from southern Coromandel to Kawhia. The richest deposits lay in the far north — the Aupouri Peninsula, that long sandspit flung between the Tasman and Pacific.

By the time the forbears of the Maori arrived, kauri forest covered only pockets, and larger tracts of the area between Kawhia in the south and Kaitaia in the north. Apart from an isolated sprinkling in the vicinity of Spirits Bay in the far north, the peninsular area between Kaitaia and Cape Reinga was denuded.

When the diggers came, it was a desolate land: endless dunes to the west, swamps and scrub to the east, and hardly a green tree in sight. At Aupouri, the Ninety Mile Beach called by Cook “the desart (sic) shore” because of its then rolling sandhills, bears underground evidence of having been clothed several times with successive layers of kauri forest. The most recent layer, carbon-dated as 3000 years old, lies buried in a jumble of peat swamp, pumice and sandstone. Most of the gum is to be found in swamps, yet living kauri do not like wet feet. At low tide, ancient logs stick up out of the channel of the Houhora Harbour. Once, though, these lands had been an immense forest of kauri. When those trees died — perhaps through fire, shifting land, or climate change — their resin sank into the bogs. Centuries later, it would be the diggers’ turn to dig it back up.

A Golden Industry

Digging for gum within the Houhora Harbour circa 1910

By the 1860s, exporting kauri gum was big business. From 1870 to 1920, it became a major source of income for Northland’s settlers and Māori alike. By the 1890s, some 20,000 people were involved, 7,000 of them full-time diggers.

First on the fields were the Northland Maori, joined later by Maori from the King Country, Waikato, and the Bay of Plenty. By the 1880s, word was out around the world, and diggers flooded in from Yugoslavia, China, England, France, Malaya and Germany.

British diggers and runaway soldiers from the New Zealand land wars mingled with fez-wearing Bosnian Muslims, who were mistaken for Turks, and Finns who were mistaken for Russians.

But the ethnic group which had the greatest presence was the Yugoslavs. Known then as Austrians, later as Dalmatians, they were a collection of distinct and separate peoples from the states of Dalmatia, Macedonia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, and Montenegro.

But it was a brutal living. “The life of a gum-digger is wretched,” one buyer wrote in 1898. The work was backbreaking, the income uncertain, and the weather merciless. Gum was like gold — but most who chased it ended up poor.

They came from everywhere: professional men and pensioners, family men and drifters, the sober and the drunk, the hopeful and the hopeless. They came north chasing a dream. Most found mud, mosquitoes, and disappointment.

A collective of Australian gum diggers at Tom Bowling Bay - Circa 1910-12

Life on the Gumfields

Diggers worked with little more than a spade, a spear for probing the soil, a few sieves, a gum knife, and sacks to carry their finds. They built crude huts (whare) from mānuka poles, sacks, and raupō fronds, with beaten-earth floors and bunks made from stretched sacking.

They trudged home at dusk through the tea-tree scrub with their pikau (a sack-backpack) heavy with gum. On the flats, gum was found two to six feet down; in the swamps, as deep as twelve. Experienced diggers sometimes struck rich veins — but more often, the earth yielded little.

From 1910, diggers were required to buy a licence costing five shillings. Gum-buyers, too, had to pay for theirs — one pound a year. Bureaucracy found its way even into the bogs.

The same collective “rolling the sod”, a simple form of strip mining.

Women, Children, and the Hurdy-Gurdy

It wasn’t only men who toiled on the gumfields. Women and children worked long hours digging, sorting, and “picking sticks” — the gum-cleaning process done at home. Later, the work was helped by crude mechanical gum-washing machines known as hurdy-gurdies.

From Mud to Beauty

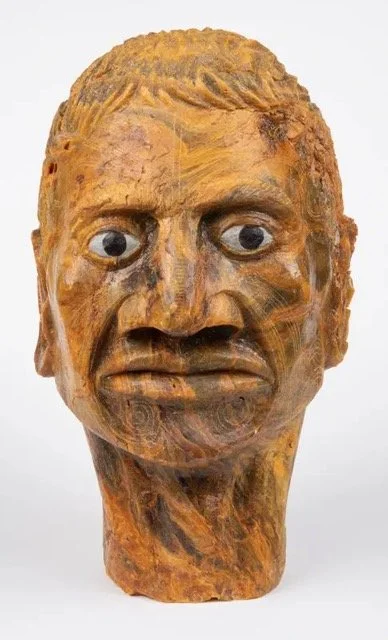

From the Ned Evans collection of the Far North Regional Museum in Kaitaia, - A realistic KAURI GUM CARVING of a Maori chief’s head, with tattooed face and staring eyes. Under Maori custom it was not permitted to make a perfect image of a particular person, so the carver was required to make a flaw — in this case a distorted ear which hardly showed.

Though most gum went overseas for varnish or industrial use — even for lining fruit and jam tins — some diggers turned the raw resin into art. In their spare hours they carved, scraped, and polished it into glowing curios: miniature lighthouses, dancing figures, Māori heads. Once polished, the dull, cloudy lumps came alive — golden, translucent, sometimes with insects or leaves suspended inside like ancient time capsules.

Spider trapped in Kauri Gum.

The gum could even be softened and moulded into balls with pictures embedded inside, or drawn into delicate golden “hair.” Local fairs offered prizes for “Best Polished Gum,” “Best Gum Ball,” and “Best Curio.”

Lighthouse carved from Kauri Gum

Decline and Legacy

By the early 20th century, the easy pickings were gone. The gumfields were mostly exhausted, and synthetic alkyd-based varnishes, developed in the 1920s, with their ease of application and fast drying times, superseded copal/kauri varnishes. And the advent of vinyl sounded the death knell for linoleum.

The merchants of Auckland — the real profiteers — had long since made their fortunes, while the diggers themselves drifted away, broken men with nothing left but calloused hands and stories.

Today, the gumlands are farmland and pine forest. Yet beneath the soil, buried kauri logs and pockets of resin still sleep, remnants of a world where hope and hardship were measured in golden lumps prised from the swamp.

Kauri gum was New Zealand’s first great export boom — a fleeting gold rush without gold — and the men and women who dug it up carved their names into one of the grittiest chapters of the country’s colonial past.

Old varnish tin . "Manufactured by Brooklyn Varnish Manufacturing Company, New York.. Made from the resin of the Kauri, an evergreen tree found in New Zealand, waterproof and never turns white"

The Kauri Gum Commission Report of 1898 advised setting aside an experimental farm for gorse pasturing, with a view to reclaiming gum lands, saying that land which could not feed one sheep to the acre had been made to carry and fatten five or six sheep to the acre when planted with gorse. Northland is now glutted with the pest, and lacks the economic strength to get rid of it.

But there is still hope. Recent advances in technology and research are breathing new life into the Kauri gum industry. Scientists and researchers are exploring novel applications for Kauri gum, particularly in fields such as biodegradable plastics and eco-friendly adhesives.

New extraction methods are now being designed to tread more lightly on the land. Precision tools and drone mapping are allowing diggers to locate and recover gum with minimal disturbance to the fragile kauri ecosystems. The goal is simple but vital: make the process efficient and profitable without scarring the forests* that produce this ancient treasure.

I can't help but think about those two gum-diggers living in the boat (see pic). And wondering whether they cooked pizza in that oven - (you idiot Lambe). Be more like a hangi I suppose - where they cooked lamb and kumaras.

I found out something else though - old gumdiggers would put green kauri gum in paper moulds and bury it under the cooking fire in their camps. “They knew just when to take it out, depending on what shade they wanted. When it was cold they would then carve it into beautiful things and polish it.” Do you reckon that's what they were doing with that fire?

* Waipoua Forest contains some of the largest remaining kauri trees. However, much of the original New Zealand kauri forest has been lost due to logging and other human activity.