THE SUN WATCHERS

By Sal Balharrie

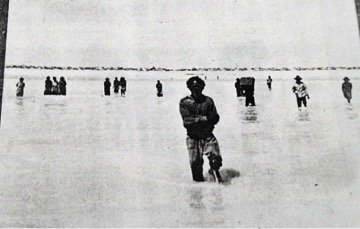

Members of the Wallal Party carry precious equipment ashore.

Unless you still sail from A to B using celestial navigation, every day we tap into mapping technology based in Einstein’s theory of relativity. Einstein had asserted the principle in 1919 but scepticism remained.

It was to be a team of Australian scientists in 1922, camped out on a beach at Wallal, north of Broome who proved Einstein correct, once and for all, by photographically mapping stars during a solar eclipse.

'A quick run down the coast brought us to Wallal. At least someone said that it was Wallal. All we could see was a stretch of golden beach that disappeared to nothing to right and left while on it the great rollers crashed their way only to be broken up in a smother of white foam.'

E Brandon Cremer, United Theatres, cinematographer on the expedition, 1922

This is an incredible story of collaboration and adventure with one shared aim – to prove a scientific fact. The simplicity of the goal was what galvanised the mission, communication and organisation. While the objective was exquisitely simple, the execution was fraught with issues and the potential for failure huge.

‘The party had grown to 30 scientists and their wives, 2 filmmakers, a photographer, a Broome policeman and ten naval officers. With 35 tons of luggage it was very cramped aboard the schooner GWENDOLEN so the ladies were accommodated on the steamer GOVENOR MUSGRAVE, which towed the GWENDOLEN south to Wallal, 300 kilometres away.’

Four teams headed for Wallal. The Lick Observatory team led by William Campbell, included his assistant Robert Trumpler, Dr C Adams, the New Zealand Government Astronomer, J. Hosking, a Melbourne Observatory member and Professor Alexander Ross, Foundation Professor of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Western Australia. Perth Observatory sent another team. The Toronto University team was led by Professor C A Chant. The Indian team comprised of astronomers John and Mary Evershed of Kodaikanal Observatory in South India. A photographer, a filmmaker, two self-funded British amateur astronomers and the Australian Navy team under Commander H L Quick made a Wallal group of more than thirty.

Across Australia, Adelaide Observatory sent a group to Cordillo Downs in South Australia while Sydney Observatory sent a team to Goondiwindi, near the southern border of Queensland. Dr Campbell assisted these Australian astronomers with their eclipse plans and equipment so that results could be compared.

‘The landing was rendered very difficult by the surf, which was heavy, and bumped the whale boat badly as it came to shore. . . a number of cases were swept away by the surf and were badly soaked.

Daily Examiner, 5 September 1922’

With a key date for observation calculated as September 22, 1922, Seven international teams set off for four locations, all hoping to catch the upcoming eclipse. A British expedition from the Greenwich Observatory went to Christmas Island to try to improve on their 1919 results. A joint Dutch-German expedition joined them.

'the eclipse track reaches Australia at Ninety-Mile Beach, a hopeless part of the coast, and strikes into the great desert. There are no facilities for landing. The desert is inaccessible, except to camels. There are no railways within hundreds of miles, and motor cars are out of the question.'

- Charting the eclipse path, H A Hunt, The Total Eclipse of the Sun, 1922.

The GWENDOLEN arrived off Wallal at sunrise on 30 August. Landing on 80 Mile Beach involved transferring everything to land using a lifeboat. A combination of the large tidal range (up to nine metres) and surf, made it even more difficult. Dr Campbell, ‘the greatest living observer of eclipses’, was the first off the boat with Lieutenant Commander Quick, keen to get preparations underway.

When the lifeboat grounded they jumped into the water and waded to shore carrying the chronometer and other delicate instruments. They were greeted by a group from the Wallal Downs pastoral station, the Wallal postmaster/telegraph operator and, around ‘two scores of aborigines.’ All were put to work carrying the precious packages through the water to shore.

'The camp is anything but a picnic place . . . the ground is loose grey sand, and, with the clearing operations and the passage of the donkey teams, the air is filled with powdery dust, which finds its way into the food and everything else.'

The Argus, 1 September 1922

Campbell chose a suitable flat site for the observation station and camp west of the Government well and surrounded by low trees and scrub. The Navy team set up the camp, s selecting sites for the twelve sleeping tents, two mess tents, two store tents and the cook’s galley, adjacent to the four observing stations. They unloaded the schooner ‘manfully and efficiently’, assisted with the erection of instruments and their shelters and generally took over camp operations. The Perth team used Wallal Downs station, about three kilometres away, as the base for their accommodation and instruments.

Food and meals were provided by the Navy with ‘near fine dining’ offered. At 6.30am each day the camp was roused by a naval officer who walked amongst the tents ‘shouting an old getting-up call used on board ship.’ Work started after a quick breakfast. They had only three weeks to prepare for the big day.

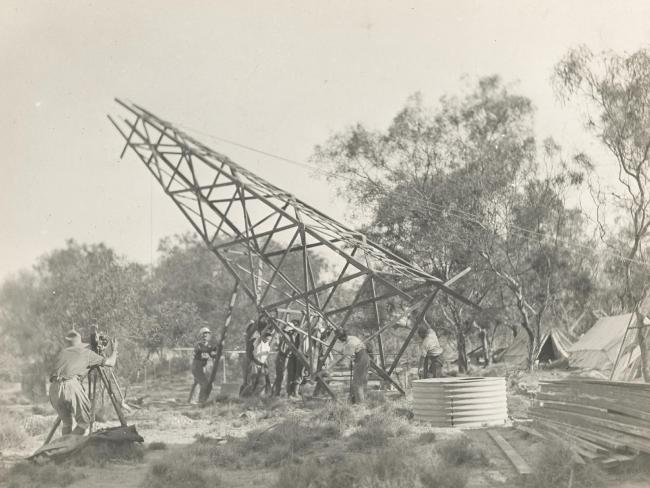

Everybody had an allotted task. From early morning until nightfall scientists could be seen ‘using pick, shovel, or astronomical instruments with equal enthusiasm.’ The women supported the scientists in a range of roles. Although the main emphasis was on testing Einstein, coronal studies of various kinds were also to be undertaken. A variety of auxiliary devices providing temperature, pressure, humidity and wind measurements were set up and tested. Time signals came from Bordeaux to Wallal Downs via telegraph and were then relayed by wireless to Campbell at the top of the 40 foot camera tower.

Dust was the major drawback with the living area soon dubbed ‘Dust Camp’. The instruments were located among the trees, but the living quarters were in an open area.

Strong winds and feet stirred up dust that blew into everything. Aboriginal people assisted by covering the ground with sand and branches and sprinkling water near the instruments.

The chief task was the erection of structures to hold the instruments, then their alignment. The ‘Tower of Babel’, so named by the naval officers because it was “constructed in five different languages” supported the 40 foot Lick Observatory coronal camera. More supports were needed for the “Heavenly Twins” - Lick’s twin 15 foot and 5 foot Einstein cameras. These cameras with precision lenses were specially designed for the eclipse by Lick Observatory. Each camera required a canvas shelter for shade as well as protection from strong winds and dust.

The main Canadian Einstein camera with a focal length of 11 foot was smaller than those of the Lick Observatory but it too required protection with a high wall and a roof that could be pulled aside for observations.

The two amateur English astronomers, dubbed ‘the British Cavemen’, created interest by setting up most of their instruments underground.

The Indian team built three large concrete piers for their 21 foot focal length camera and other equipment, protecting them with tents and a wooden structure.

The Perth Observatory team a few kilometres away determined the longitude of the Wallal site from radio signals. Their small twin cameras and twelve inch reflector were also set up to photograph the corona and investigate shadow bands, those thin streaks, light and dark, that move across the ground before and after totality.

The weather was perfect in the lead up to the eclipse with the clear nights needed for adjusting observations. The second week saw numerous rehearsals for the big day:

'Mr James Kean, one of the naval party, would stand on a box with a chronometer before him. A certain second would be chosen for the beginning of the total phase, the zero hour, and at precisely six minutes before that epoch Mr Kean would call out ‘Six minutes before!’ Everyone would assemble be at his post. Four minutes later he would call ‘Two minutes before!’ – Then ‘thirty seconds before!’ Director Campbell would be looking through the finder of his Einstein camera and when he would (in imagination) see the moon just cover the sun and the corona flash out he would shout ‘Go!” Then Mr Keane would count the seconds, One! Two! Three . . . Fifty-nine! One Minute! One! Two! etc until some seconds after the time totality was supposed to end. This practice continued until the fateful day arrived.'

Professor Clarence Chant, Toronto University

Two minutes before totality. The landscape assumed in turn a yellowish tinge then a greenish blue, then a purple colour, and the shadows cast by the narrow crescent sun were sharp and harsh.

The weather was perfect. At 13.40 hours, on 21 September 1922, ten minutes before the moon’s silhouette passed across the sun, the signal for action sounded. After final adjustments to instruments, slides for cameras were placed in position, shutters tested and retested and all gathered around their allotted instruments to await totality. The Aboriginal people, it is said were frightened and kept out of sight.

The temperature dropped by about eight degrees, there was an absence of bird life and even the flies ‘appeared to become quite paralysed, so that one could pick them up as if they were dead.’ At the moment of totality the eclipse program started and it was progressed ‘with clockwork precision’. There was only five minutes and 15.5 seconds to obtain the evidence that would prove or disprove Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Dr Adams, New Zealand Astronomer assisted by his wife took exposures from inside the Lick 40 foot camera, the navy’s Mr Keane provided audio time signals and Campbell was in charge of the smaller Lick Einstein twin cameras with two naval officers changing the glass plates. Trumpler guided the 15 foot cameras with assistance to operate the plate holders. Not one second was wasted.

At the end of the day Campbell, Chant and the Perth Observatory team all expressed satisfaction. The British amateurs were disappointed because their self-recording magnetic instrument had failed to register. The Indian team later expressed regret that they had been unsuccessful under such ideal conditions and all their plates had failed ‘for one reason or another.’

Campbell was confident that the photographs that they had collected would be ‘of great value to science’ but he could not as yet say more.

'Men of science feel the necessity of absolute conviction before venturing public expression of results.'

W. W. Campbell

The most important phase in the project was yet to come. Hopes for an announcement in Broome were dashed. The development of the huge glass photographic plates was started at Wallal but temperatures in the darkroom tent could not be controlled, night air was often moist and dust was an issue.

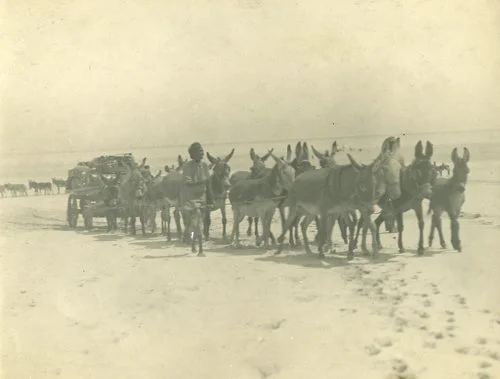

They decided to take the plates to Broome where suitable space could be found to develop them as well as a source of ice for cooling. The camp was dismantled and the instruments and plates carefully packed and taken by donkey team to the shore. Getting the luggage through rough seas and onto the schooner moored some miles off shore caused delays. The Wallal sun watchers returned to Broome on the 28 September.

The plates were developed in Broome but the large number of stars recorded meant that more time was needed to study, measure and compare them with those that Trumpler had photographed in Tahiti. The 270 kilograms of glass plates were packaged for transport to Sydney and would not be shipped to the United States until 19 November 1922.

The British, Dutch and German expeditions to Christmas Island all failed due to cloud. So it was on the Wallal results that Einstein depended to prove his theory of general relativity.

The media clamoured for news and the scientists were under intense pressure. Campbell reiterated that there would be no hasty announcements. They did not start work on the plates for some time. The precious cargo arrived at the Lick Observatory in December 1922 but Trumpler did not return home until February 1923. It was only then that both he and Campbell could throw themselves into processing the plates.

Campbell and Trumpler independently selected and measured three pairs of Wallal plates showing from 60 to 80 stars. They then compared them with those plates taken by Trumpler in Tahiti, three months before the eclipse. They found that the displacements of the stars close to the eclipsed sun had a mean value of 1.74 seconds of arc. The value expressed in Einstein’s theory was 1.75, almost exact agreement.

On 12 April 1923 Campbell cabled Einstein in Berlin to say that the Lick Observatory team had confirmed his prediction. A cable to the Astronomer Royal expressed Campbell’s confidence that there would be no need to repeat the Einstein test at the upcoming September 1923 eclipse. Chant’s Toronto team also released its results. Although not as definitive, they also confirmed Einstein’s prediction.

Einstein’s quest for truth was over. It had been proven at Wallal, with the support, interest, generosity and hospitality of the Australian people.