The Weather Guru

Our short story last week on Roger Badham’s OAM has turned into a trifecta of articles. This week, thanks to the generosity of Andrew Wilson, we bring you an interview from his 2020 book “Blue Water Classics”.

Its a rare insight into the world of modern forecasting and makes me realise there’s more the weather than downloading Predict Wind.

Next week we’ll bring you the story of BRIGAND Roger’s generous and fascinating South Australian restoration project.

Image Andrew Wilson

My name is Roger Badham and I’ve forecast for more than 40 Sydney Hobarts. And it’s not just forecasting these days; it’s the whole strategy and tactics of the race. The tactics is boat-on- boat and the strategy is boat-on- weather, or the environment.

In the old days, the CSIRO used to send a guy up to talk about currents and whatever, and the whole data thing was missing.

That was before computer models and whatever, so your input was obviously more vague, but it actually put a lot more emphasis on you, the person, providing the information. These days, the weather forecasts are completely dominated by the computer models, because they forecast three to five days ahead with pretty good accuracy. In

the broad sense, they’re pretty good. The same with the ocean currents, too. There’s a lot more digital and exacting data going out across the race period, but when you get down to the nitty- gritty and the fine detail, you’ve still got to think.

OR BE LUCKY?

The winners don’t acknowledge luck and the losers will always say they had bad luck. Every time. It often comes down to: Do I tack on this shift? Or don’t I?

In the first six hours, all the 50-footers and 40-footers, and all the big boats, they’ll all be in a group. Are you going to tack out on a shift that the other guy will just say, “No, I’m going to go a little bit further on port, and come in a little bit closer and that’ll give a bit of separation”? And that separation can then magnify as you go down the track a bit. And that’s the boat race.

Primarily, to win the Sydney Hobart it helps enormously if you get to the Derwent at the right time of day, which is at about two o’clock in the afternoon.

BECAUSE THE SEA BREEZE IS IN.

Yes. And so you carry the breeze all the way up the river. That can take an hour away from a competitor of another class – if you can arrive at the right time, because the Derwent is open, as a rule, between 1pm or 2pm and maybe 10am to 12pm.

SO YOU CAN PICK THAT FROM THE START, WHICH CLASS WILL GET THERE PROBABLY AT THAT TIME.

You can often pick that from the start, and say that the 50-footers might be favoured the next day. It’s becoming easier in that regards, but to pick the boat within the class... Well, there are good boats, the new boats, and the good boats have good crew. They make less mistakes by physically handling the boat and also they have the good navigators. Good navigators are bloody hard to find.

Because navigating is not just staying on this course, it’s everything. In the old days, it was 90 percent just knowing where you were, and making sure that you were where you thought you were. Now, where you are is one percent, and it’s 90 percent about where you want to be.

You’re working with the strategists, or the clever people at the back of the boat, and the skipper, trying to put your boat in the right position, in the next three, six, twelve, whatever, hours ahead. It can come down to sails – you might choose something better than the other guy. It’s short-term good sailing versus long-term strategy of where you want to be. Again: Do we attack on this shift? Or, No, the strategy is going to win out here; I want to go until I definitely see the breeze come left. Often – not always – it can be port tack biased, the route, so therefore starboard can often be a bad tack, and to hang out for the breeze to lift you and take you around.

“OFTEN THE ROUTE CAN BE PORT TACK BIASED, SO THEREFORE STARBOARD CAN OFTEN BE A BAD TACK.”

Also, there’s the night-time shift, when you’re on the breeze: Should I go right to the coast, hoping to hold the left-hand shift if it’s south-east going easterly? Or are you better to try and hold off a bit, the current’s a bit better out wide, maybe a little bit more pressure, but to get out there I have to put in a short starboard, which is not a good look. Or you have to soak people before the southerly change in trying to get out to where you want to be.

YOU’RE ESSENTIALLY A GUN FOR HIRE, A WEATHER FORECASTER. HOW DOES THE RACE PLAY OUT FOR YOU? WHAT DO YOUR CLIENTS ASK OF YOU DURING THE RACE?

I hope that no-one will ask and I can retire! But they start asking usually by June (smiles).

In June the owners start locking you in and asking you what you can do, what do I need to do, that sort of stuff. Some guys coming from overseas want to lock in your thoughts, or want to know what they should be doing and preparing for. Some people want previous race statistics that they can run through. All sorts of things.

I don’t do all the boats in the Hobart either, but generally the well-heeled crews are the ones that usually have good people on board. They’re the ones that I’ve worked with over many years. There’s a whole list of things you’ve got to have for the boat, and one of them is weather forecasting: “I’ll get Clouds [Badham’s nickname] to do that.” That type of thing.

The number of people who ask for a forecast increases as you come to about a week prior to the race. They’re all thinking about the weather then. In the old days, it was the same thing, but I didn’t do it by email in the old days. I’d do it with a phone call and you’d send some stuff out. Or you’d just do something on the morning.

I REMEMBER TALKING TO YOU LAST YEAR, TRYING TO CATCH UP WITH YOU AFTER THE START OF THE HOBART ON BOXING DAY, AND YOU WERE FLAT OUT.

It’s always a busy day. It’s hectic. About a week out, I do an email service. I send an email every day, an update, where I give an outlook of what I think the race is going to be, on day one, two, three. And obviously as we get closer and closer, it gets more and more accurate. I also home in every day on a different aspect of the race.

Each day I’ll pick a topic – currents, or the sort of clouds that you’ll see, anything that’s relevant to the race – and what they should be learning or thinking about.

My feeling is that by the time Boxing Day morning comes, and they get the full set of notes and have done their homework for the previous eight days, they should be weather-free. They should be fully cocked and then it’s up to them.

“EACH DAY I’LL PICK A TOPIC – CURRENTS, OR THE SORT OF CLOUDS THAT YOU’LL SEE, ANYTHING THAT’S RELEVANT TO THE RACE.”

The happiest time of my Boxing Day is 1pm. They have the official briefing from 8:30am until 9am. I turn up at the Club at 9am, and sit out on the sea-wall to the south, and they all come out and pick up hard copy of what they’ve already got by email.

There’s one file that might be a late one that they haven’t got since I sent the notes out at 5 and 6am, and that’s available for them on a thumb drive.

Also, any late charts, or excess charts that I didn’t send by email. There’s a whole set of stuff that’s useful. It might end up being twenty megabytes or so that can go on the thumb drive.

They’ll all want to discuss things, shoot the shit. Regular people that I often only see once a year, or talk to a lot on email or on the phone.

Basically, everyone is usually on their boats and gone by 11am on Boxing Day. Then you usually get quite a few phone calls between 11am and 1pm: “We’ve just gone over this” and, “What do you think about this?” “It’s 70 degrees in the Harbour – what do you think the chances are of it going to 50?”

DO YOU WATCH WITH INTEREST TO SEE WHO WINS?

Oh, shit yeah. On a typical Hobart, there are 80 or 100 boats or so. I’ll be looking after 40 or 50 of them. I’m guaranteed to have the winner. Not guaranteed – but you know what I mean – the likelihood is that I will have forecast for the winner.

DO YOU HAVE MORE INTEREST IN CERTAIN TYPES OF WEATHER PATTERNS THAN OTHERS?

Not more interest, but there’s a lot of degrees of difficulty. There’s always little bits that you’re highlighting where you say, “I’m going for what’s going to happen here, but this could happen and you got to watch for that.”

The classic one is the south- westerly changes in Tasmania where you get that lead trough off the east coast of Tassie, or even the north-east coast, and it’s soft in there [i.e., a lack of breeze]. Sometimes that softness off the east coast can extend right out to the rhumb line. That’s 50, 60 miles offshore.

You might have some cloud lines or some cloud influence that you’re thinking about there as well. There’s a lot of things in that situation.

As a rule of thumb, it’s a death knell to go to the Tassie coast too early. On some occasions, it can actually work – some occasions – mostly not.

WHERE DO YOU GET ALL YOUR INFORMATION FROM?

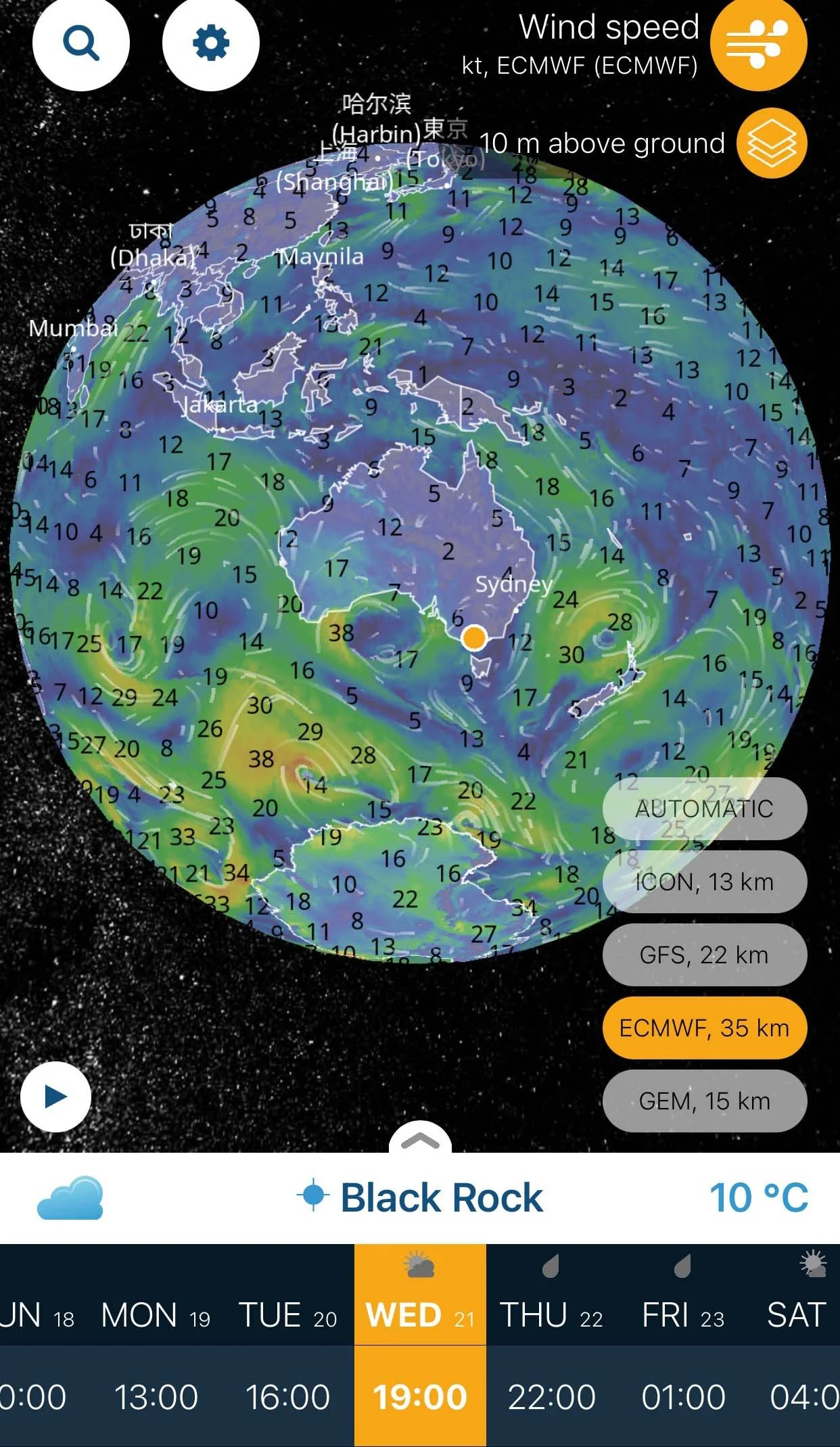

These days it’s just the computer models.

IS IT PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE?

Some are and some aren’t. Some of them you have to pay hefty dollars for. But these days there’s a service in New Zealand, Jon Bilger’s PredictWind. He pretty much purchases all the grib files and has them available on his website. I pay quite hefty amounts commercially to buy all the files, because I don’t just use them in Australia, I use them globally. You pay for some of the models, but for the Hobart, they can use most of those models.

DO YOU CONSIDER YOUR CAREER AS A SCIENCE OR AN ART, OR IS IT A BIT OF BOTH?

I’ve always got more knowledge than they do. I have a lot of knowledge and a lot of experience now in forecasting marine weather, so therefore I would say now it’s a science, but it’s a science where you can still get it wrong. It’s not absolute. Just by the chaotic nature of weather and the fact

that things change over time. And errors creep in and they magnify over time. But in the earlier days, it was a combination of science and art. It’s become much more disciplined with the computer models now being more accurate.

HOW DID YOU GET INTO WEATHER FORECASTING?

I started when I was young. I was at university. I have a degree in maths and physics. I did a PhD in numerical meteorology, a postgraduate and post-doctoral work in that. I went into business with a colleague. We wanted to do environmental consulting, but we were forty years too early. We couldn’t find many customers. This was in the mid-’70s. We had some customers doing different things. But a lot of people said, “Do you do forecasting?” Because the Bureau of forecasting was then the forecast of the day – with an outlook of the next day. And we said, “No, we don’t do forecasting.” But it got to the point where we said, “Well, maybe we will.”

We picked up a lot of clientele doing forecasting in agriculture, some marine work. But particularly in the media – radio, television and newspapers.

I remember I got Frank Bethwaite [boat designer, author and Olympic meteorologist, who died in 2012] to come along and talk to a NSW Meteorological Society meeting in 1973 after the 1972 Olympics. He spoke, and I rang him a few days later and said, “Look, you spoke about trying to nail down these wind shifts on the Olympic course; there’s a lot of really good work that’s been done in the States on this theory.” He wasn’t interested at all. But that got me thinking.

When Don Watt and I were working for Channel 7, Ted Thomas, the managing director, called me in one day and said, “I’d like you to get in the boat park on the weekends if you could; I’ve just signed up this young guy to sail skiffs.” That was Iain Murray.

I worked with Iain Murray all the time he was in 18-footers from 1977 through to 1982. They [Murray, Andrew Buckland and Don Buckley] won everything

in that period, including an unprecedented six JJ Giltinan Championships [unofficial Worlds].

That got me into marine and sailing stuff again. In 1982, I went full time into yachting meteorology.

I remember getting Iain ready for the 1983 America’s Cup with Syd Fischer and Advance. I also spoke to Chink [John Longley], with Australia II, and said, “Do

you want a meteorologist?” And he said, “Oh.” I said, “It’d be useful over there.” And he said, “Oh. How much would it cost?” I had a family already, and I said, “A couple of months of employment, some gear and everything else, it’ll cost you a few thousand dollars.” And he said, “We can buy a new genoa for that. No way!” Things have changed rapidly since then. Rapidly...

I was the official race forecaster for the Sydney Hobart for a few of the years; it would have been in the late 1980s. I did the official briefing and so on...

When the America’s Cup was in San Diego, I was there, forecasting for that. It was also Christmas time, so the official forecasting for the Sydney Hobart went back to the Bureau. They were pleased to do it then; they wanted a bit of a profile from it.

WERE YOU ANNOYED TO LOSE THE HOBART GIG?

I thought, I don’t care. I do very little forecasting here in Australia, really. From the mid-1980s, most of my work has been with teams offshore: America’s Cups, around-the- world races and that type of thing.

I did the Invictus Games here in Australia. Someone asked, “Can you do some forecasting for the sailing?” And then they asked, “Can you do all the outdoor sports?”

“‘IT’LL COST YOU A FEW THOUSAND DOLLARS’ - AND HE SAID, ‘WE CAN BUY A NEW GENOA FOR THAT. NO WAY!’ THINGS HAVE CHANGED RAPIDLY SINCE THEN.”

In Australia it’s usually a few regattas with the Blue Water series and the Hobart.

WHEN YOU WERE FIRST STARTING, WERE MORE OF THE SAILORS ACTUALLY MARINERS, IN THE SENSE THAT THEY COULD READ THE WEATHER THEMSELVES?

I’ve worked with the best sailors in the world. Pretty much all of them have an absolute feeling and instinct about the wind and the nature of the wind they’re sailing in. But if you scratch the surface, they know bugger-all. And if you could put a bit of science into it, they could learn a lot more.

But when things turn to custard, the good sailors come out. I remember talking to one sailor after the ’98 race, a good sailor who I still work with. I said, “What was the main thing you took away from that race?” And he said, “I’d look more carefully at who I sail with.”

WHAT YEAR HAD THE WORST WEATHER THE RACE HAS SEEN IN YOUR OPINION?

1993 was by far the hardest Hobart ever. They can talk about any other year, but it was blowing a southerly six hours after the start, and it was still southerly at Tasman Island.

It was just bang, bang, bang. They had gale-force winds, strong winds, and the sea... Basically, with every boat, either the sailors failed, or the boat failed, or it just got too hard.

97 winner of the 1993 Sydney Hobart

BECAUSE IT WAS A SOUTHERLY SO LONG, WAS THAT IN A SENSE EASIER FOR YOU TO FORECAST?

That was in the days when the computer models were getting going. They were there, but they couldn’t be relied on a long way out.

There was a small low pressure system. It was definitely a low, but it wasn’t like the ’98 low, which was highly intense and had unbelievable winds. It just had gale-force winds that followed the fleet down through the whole race. So they were trapped with it the whole way. That’s quite unusual. There’s been a lot of races where there’s been some hellishly strong winds in different places: Tasmania, Storm Bay, whatever. But that one was unusual, just in the fact that there was such longevity to the system by a long way.

With 1998, it was the intensity of the low pressure system that developed. The forecasts on the morning were not good. The modelling was getting reasonable by then, but it wasn’t fantastic. The Bureau had its own modelling

“WITH ’98 IT WAS THE INTENSITY OF THE LOW PRESSURE SYSTEM THAT DEVELOPED. THE FORECASTS ON THE MORNING WERE NOT GOOD.”

and the model would run every twelve hours. So the model that came out overnight had this nasty low develop, but it was off the east coast of Tasmania and went away to the east.

The only model that got it right was the US model. It nailed it pretty well. It didn’t have quite the intensity of winds, but it certainly had 50-knot-plus winds, right around this intense low in Bass Strait. I put that in my notes. I put the model in and I said, “If this comes true, it’s really bad. But if you look at the European model, and the Australian model, it’s probably going to be off Tasmania, not in Bass Strait.” The difference was chalk and cheese. Because one was where they were going to be – and one was where they weren’t going to be.

3PM on 27th December 1998

CAN YOU GO INTO SOME MORE DETAIL ABOUT MODELLING FOR ME?

The air and the ocean are fluids, so therefore if you can measure everything at time zero, you can then solve the hydrodynamic equations.

There are six equations that govern everything there is about fluids, in terms of the transfer of the heat, and momentum through it. And the vorticity of the air, the compressibility of the air, the instability of the air and the water. When you solve those equations you can theoretically progress in time and see how far out you can keep track of what you forecast.

This has been known for a long time. There was a very clever meteorologist in the 1920s that actually did this by hand, solved the equations and spent several years doing the mathematics.

He said, “What I need are 80,000 people in the Albert Hall in England and for each to have one job...” In other words, he was saying, “I need a computer.”

He tried to forecast the weather twenty-four hours ahead at his home in Europe. He was out by an order of magnitude, so he didn’t get it right. But he broke several laws, mathematical constraints, that hadn’t even been invented or discovered at that time.

It was long realised that you could solve this thing if you could have computing power. The first computer that was really running was ENIAC in the States after the war, in the late ’40s, early ’50s. One of its first jobs was working with some of the cleverest meteorologists that were ever around.

The sophistication of the computer model was just to say: Let’s take the atmosphere in two levels. There’s ground level to 20,000 feet, and then 20,000 feet to 80,000 feet. It was a very simplified model – something you could do these days on a spreadsheet. Back then, the computers were very clunky and not very powerful.

Since then to now, the computer horsepower is just unbelievable.

The fact is that the modern global computer model has grid points across the whole world

every ten kilometres. And it’s not just two levels thick through the atmosphere; it’s eighty levels thick. Eighty! There’s a grid point every ten kilometres, eighty levels thick, and twenty levels down into the ocean.

The whole thing is running. You’re turning the sun on and off, and you’re spinning the earth, and you’re solving the equations that keep track of all the weather systems.

This is all solved through the computer. They put in time zero, where they take all the world’s information, which mostly comes from data from satellites, both on the sea and on the land, and then also all the human observations and satellite wind observations. Every observation goes in at time zero, which is 12 Zulu and 00-Zulu GMT,/UTC which corresponds here to 11pm and 11am in summertime. That’s the initial time. All the data goes in, and the computer cranks ahead for a couple of hours and spits out what’s going to happen in the next ten to fifteen days ahead, based on pure hydrodynamics and the initial conditions.

And the most important thing is the initial conditions: Did I get that exactly right?

And the answer is, No. You can never get it right. You can have an observation from Sydney Airport, from Sydney Observatory, from North Head, but not the locations in between. You don’t get it exactly right, because your grid points are every ten kilometres.

You’re always hungry for data. You just don’t have enough. In fact, half the run-time of the model is spent just getting the initial conditions right.

The modern model doesn’t just run once, it runs maybe 30 or 40 times, because what they do is then tweak the initial conditions’ data. They say: Let’s say that this wasn’t quite as it is now; let’s just change a little bit here and there and run it again and see what the difference is. So you see where there’s big differences in the model and you see where it’s quite stable.

That’s called ‘ensemble model’.

SO IT’S A MORE RELIABLE COMPUTATION? IT’S LIKELY THE WEATHER IS GOING TO GO IN THAT DIRECTION BECAUSE, WHEN WE TWEAK IT, IT KEEPS GOING IN THAT DIRECTION?

Exactly. The big players are the US with NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] and the UK Met Office. There’s also a mob called the European Centre for Medium- Range Weather Forecasts, which is funded by the European nations.

That first started in the mid-’70s, and they started operationally forecasting in 1979 – and that is still the world leader. They put a lot of money into this thing – and a lot of effort – to stay number one. If you look at the time between

the mid-’70s and now, they have a model now which is operational four times a day, but mainly twice a day, globally. This is a system that in its total history is worth billions and billions of dollars in terms of man-hours.

Australia, up until the late ’90s, was a major player in meteorological modelling. We had our own. About ten or more years ago, Australia said, “Our modelling is not as good as the other guys.” So we now run the UK Met Office model under license, which is called the Unified Model. It runs on a global scale, it runs on a regional scale, and on a small scale of the cities. It’s unified within.

SO BASICALLY, WE’VE BOUGHT A WEATHER MODELLING APP FROM THE BRITISH, BECAUSE OUR WEATHER MODELLING APP WAS CRAP.

The New Zealand office bought the British app as well.

SO WHEN WE WATCH THE NEWS, THE INFORMATION THAT IS BEING BROADCAST HAS ACTUALLY COME ALL THE WAY FROM THE UK.

It’s from here in Australia, but it’s under license. And the seven-day forecast that you see, it’s very likely that the last four days is probably the European model. Because theirs is better.

FASCINATING. YOU MUST HAVE A VERY INTERESTING PERCEPTION OF THE PLANET AND HOW IT OPERATES, KNOWING WHAT YOU KNOW?

In terms of actual meteorology of the planet, real-time meteorology of the planet, there wouldn’t be many people who would do what I do. I forecast for yachting all around the planet, every day.

“THERE ARE PLACES THAT I KNOW REALLY WELL. ANYWHERE WHERE THE AMERICA’S CUP HAS BEEN, I’VE SPENT FOUR YEARS STUDYING IT.”

I’ve also been to most of the sailing places in Europe, from Sweden down to the Mediterranean, quite a number of times. So if someone says they’re going to do a regatta

in the Med, I know what the weather normally does there in the summertime.

When I retire, hopefully tomorrow (laughs), that knowledge will go to the grave with me, I guess.

The computer models are still better than I am, but you’ve still got to take into account your experience of sailing in that particular location.

There are places that I know really well. Anywhere the America’s Cup has been, I’ve spent four years studying it. I’ve done a PhD study on all those places, every one of them.

I used to develop my own little statistical models that ran in conjunction with the global model. In fact, in the early days, they didn’t have global models, so it was me.

I’d develop statistical models that were good. That’s what I still do. I had a meeting when I was in New Zealand about doing exactly that for the next America’s Cup. I’ve worked with team New Zealand for 20 years now. Makes me half Kiwi, really!

EVERYONE HAS SOME SENSE OF AWE OF THE WORLD, BUT YOU KNOW IT FROM A MUCH BROADER AND MORE INTIMATE LEVEL AS WELL, DON’T YOU?

One of the funniest things that I’m in awe of sometimes is the duality. I might be forecasting for somewhere in the North Sea, and also somewhere in South America – at the same time. You can see the same systems developing that are a little bit abnormal. You might get some sort of blocking pattern, with an intense low in the wrong place, and the atmosphere is doing it at the same time in a number of different locations. It’s sort of weird... It happens enough that you start to think, What are the drivers here?

That’s where the climate modelling comes into its own, in terms of looking at things like global warming. If you don’t believe in global warming, you don’t believe in glasshouses.

It’s just getting warmer. The water is getting warmer. The big thing will be the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic.

“EVERY NOW AND AGAIN, DURING THE YEAR, SOMETIMES ONLY A WEEK OR TWO BEFORE THE RACE, YOU SEE A NASTY SYSTEM IN BASS STRAIT AND YOU THINK: IF THERE WAS A YACHT RACE NOW, THERE’D BE CARNAGE.”

The Gulf Stream runs up the US coast and then it runs across the Atlantic, and feeds in across all of Europe, around England and across and into the North Sea. The little mini-Ice Age they had in the 1400s, or whenever it was, was because the Gulf Stream meandered off for a while and the whole place froze over.

You get to a point of imbalance where the Gulf Stream is not going to behave exactly as it used to. And we have the same thing. Our east coast current is a western boundary current. It’s exactly the same phenomenon, but it’s not as dynamic.

It comes down the east coast with warm water, and spills into eddies, but it doesn’t then trail off and go all the way across the Pacific. It gets absorbed into the system. The southern hemisphere is totally different to the northern hemisphere. The northern hemisphere is mostly land with some oceans. The southern hemisphere is mostly ocean with a bit of land.

If you look at the southern hemisphere looking down from the poles, it’s basically water with a few blocks of land. The few blocks of land are Australia, South Africa, and South America with the Andes. They’re the big players in terms of the dynamics of the southern hemisphere.

And Antarctica’s not symmetric – it’s quite asymmetric, so you tend to see that the whole circulation is asymmetric across the planet.

Every now and again during the year, sometimes only a week or two before the race, you see a nasty system in Bass Strait and you think, If there was a yacht race now, there’d be carnage.

But because the race is only held from Boxing Day, the likelihood of getting something really nasty is pretty low, but occasionally you nail it.

DO YOU FEEL A SENSE OF RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE SAILORS WHEN YOU SEE INTENSE SYSTEMS LIKE IN ’93 AND ’98?

A huge responsibility. Since ’98, you see other yacht races postponed by twenty-four or forty-eight hours. The CYCA was the first club to really introduce that, and it’s now copied by most yacht clubs around the world. I’ve forecast for a number of around- the-world races where starts have been postponed by twenty-four or forty-eight hours.

SOME DIE-HARD YACHTIES WOULD SAY: “I WANT TO GO OUT, I WANT PUT MYSELF TO THE TEST WITH THAT.”

It’s a trade-off. In the end, it’s better that they do [postpone the races due to weather]. The modern plastic or carbon boats just don’t withstand the constant pounding of waves. In the end, something breaks. There’s a certain number of repetitive thumps you can get before you either start to see some delamination occur in the hull, or a fitting will break, be it on the mast or the deck, or whatever. That’s just a fact of life. They’re built to the tolerance of: I want to win this race and I’m going to expect normal conditions; I’m not expecting extreme conditions for a prolonged period of time.

WHY DO YOU THINK THE SYDNEY HOBART IS WATCHED BY MILLIONS OF PEOPLE AROUND THE WORLD, AND SAILORS GO BACK TIME AND TIME AGAIN TO RACE IT?

First of all it’s at Christmas time, so there’s nothing else happening. And that’s worldwide. There’s no other yachting happening on the day after Christmas Day. None at all. So everyone can focus on the race.

Second, the average Australian likes to see what happens, but they hate the yachties because they’re all rich bastards. Whereas most of the yachties in it aren’t rich bastards, they’re just yachties, but a lot of owners are rich.

“TO WIN THE SYDNEY HOBART, IT HELPS ENORMOUSLY IF YOU GET TO THE DERWENT AT THE RIGHT TIME OF DAY, WHICH IS AT ABOUT TWO O’CLOCK AFTERNOON.”

Third: It’s the only race that goes from 34 degrees south to 43 degrees south. At that time of year, you’re going across the region of high pressure. You’re basically going from easterlies to westerlies. That makes it a really interesting race because you’re going to transition between the two.

You’re going through the ridge into high pressure, going from stronger winds with an easterly or northerly quadrant, to stronger winds, maybe with a westerly or south-westerly or southerly quadrant. In between it can lighten off, or you can get a messy front that gives the ridge that you’ve got to go through, which is soft, or the front transitioning one off the other goes through, which means you can get a blow.

But the race is getting shorter. It used to be a seven-day race, and then a six day-race. Now it’s basically a two-and-a-half-day or three-day race at most.

The leaders get there in under two days. Because it’s faster now, you can stay in more of the one weather pattern. Over four days, you’re more likely to see

the transition; over three days – probably, and two days – maybe not. Typically, at that time of the year, the transition from one high to the next high will be about four to five days.

Apart from the F1 car racing – that came through yachting in the last ten years – I’ve only done marine. It’s all I’ve done here, for better or for worse.