“We the Navigators” at Fifty

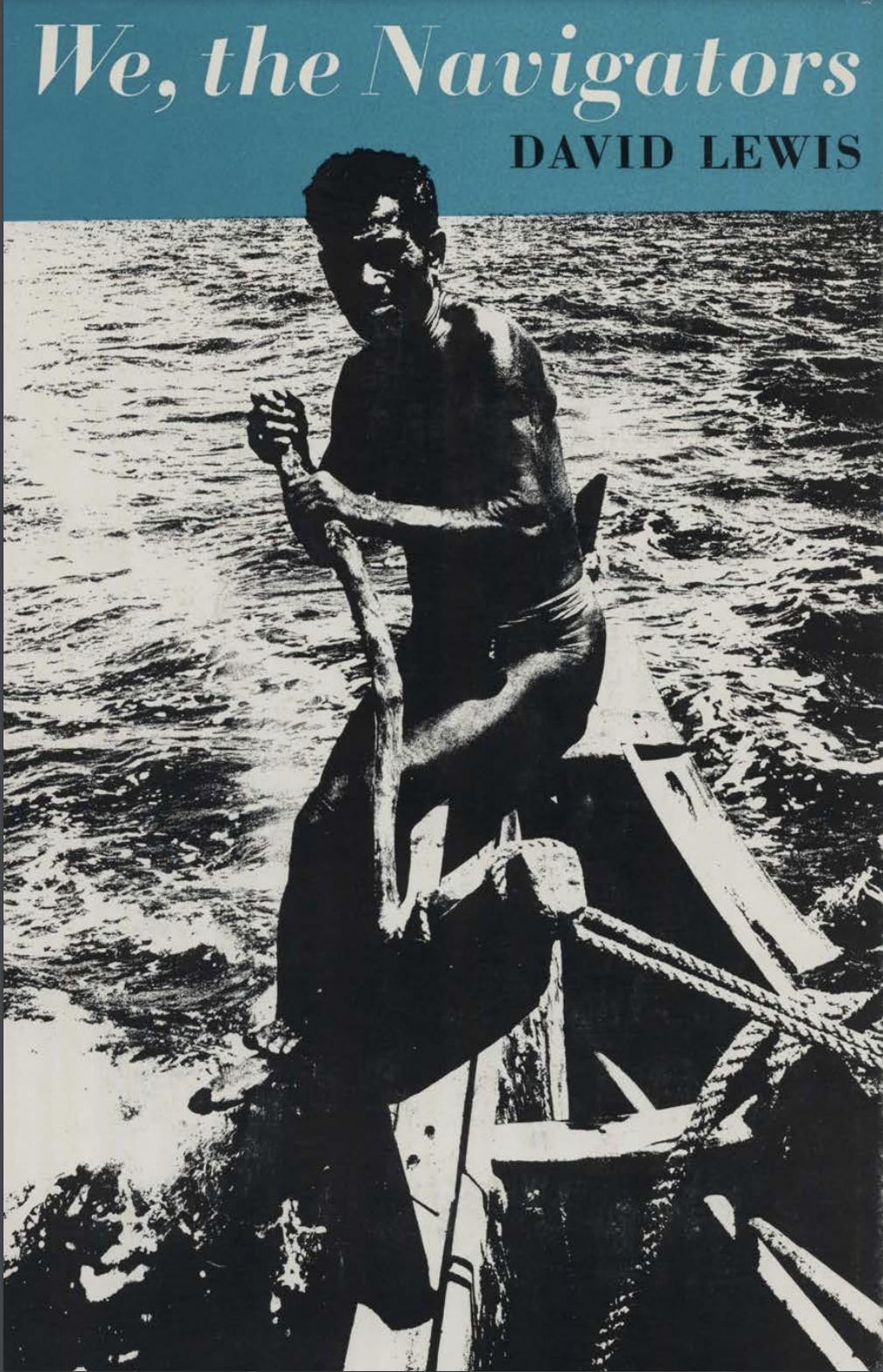

I was browsing a second hand bookshop in Auckland this week and came across an old copy of “We the Navigators” by David Lewis. I had read the volume decades ago and remember it as being almost too good to be true. Perhaps existing in the grey area between academia and storytelling, it addressed the intriguing question of how the peoples of the Pacific navigated the trackless seas.

It’s twenty years since Lewis died and exactly fifty years since the book first came out.

Amazingly this book, published by ANU Press is part of the digitisation project being carried out by the University, to make past scholarly works available to a global audience. You can (legally!) click on the image above to download a full copy

I was worried that his ideas may have been overtaken by more up to date thinking but a chat with Peter McCurdy, the respected New Zealand marine historian, reassured me that his theories are watertight to this day, and stand up to modern scrutiny.

Lewis was a fascinating man and this twenty year old obituary by Colin Putt paints a revealing picture.

David Lewis is dead. Into his long life he packed as much adventure and achievement as any man, but he will be most remembered for making known the traditional systems of navigation used by the Pacific peoples and for leading the movement of private enterprise into the bureaucratic preserves of the Antarctic.

Lewis was born in England, of a Welsh-Irish family, and brought up in New Zealand and Rarotonga, where his unconventional father sent him to the Polynesian school - for ever after he was really a Polynesian under the skin. He always called himself a New Zealander.

In his late teens he took to mountaineering and skiing in New Zealand. He was short, sturdy and tough, well suited to the strenuous mountaineering of those days.

He left New Zealand in 1938 to finish his medical training in England, then joined a British paratroop regiment as a medical officer. After the war, married and working as a doctor in London, he became involved in setting up the new National Health Service.

He seemed then to have left the Pacific and the mountains behind, but then his marriage broke up and he was set adrift.

Lewis would admit later to having been often married, and to numerous less formal relationships. Throughout his life he was an enthusiastic, happy, unashamed womaniser but he was as much seduced as seducing. Women were strongly attracted to him; a succession of beautiful, intellectually superior and strong-minded types sought him out.

Before the failure of his marriage he had been bitten by the sailing bug and when the first single-handed trans-Atlantic race was announced in 1960 he decided that now, without family ties, he could get a small yacht and enter.

This he did and in spite of a chapter of accidents he finished third (Francis Chichester came first) and wrote a book about it. His style was very readable and he was embarrassingly honest about his own mistakes and shortcomings; the book was a success and was to be followed by 11 others.

After the race he returned to England and medicine, but not for very long.

His bedside manner was unusual - sometimes he would advise a patient to "see a proper doctor". When living on Dangar Island in the Hawkesbury River, examining a patient with his best professional manner but dressed only in bathing trunks, he might look up to see his hens in the house, fouling the carpets, and he would roar at them, "You bastards".

When he decided to go adventuring with his second wife, Fiona, and two small daughters, he built the ocean cruising catamaran REHU MOANA and cut his ties to the National Health Service.

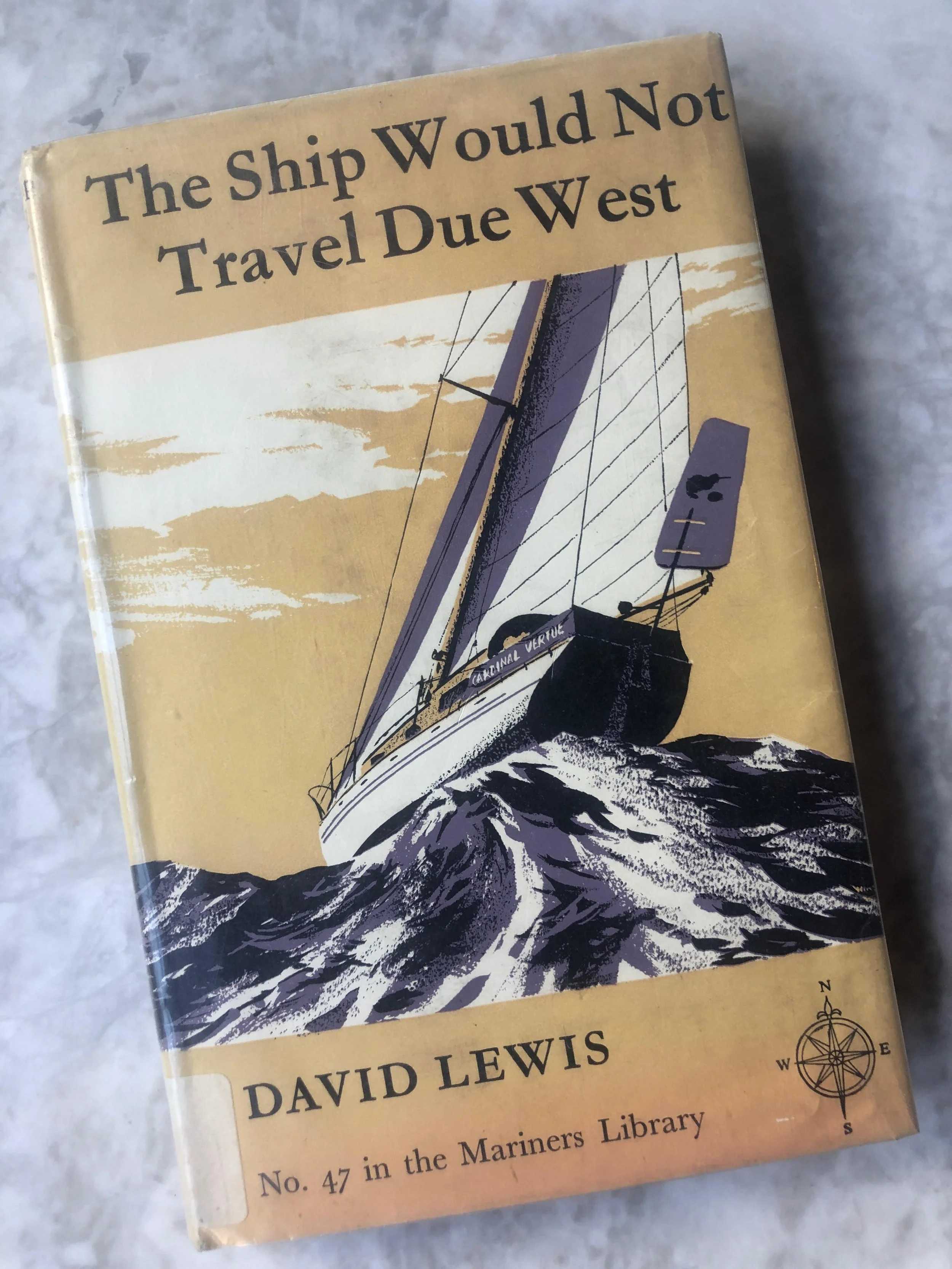

David and Fiona aboard CARDINAL VERTUE

After a fairly disastrous maiden voyage towards Greenland, he entered the 1964 single-handed trans-Atlantic race, picked up his family in the United States, and set off to circumnavigate the world by way of Magellan's straits, the South Pacific and the Cape of Good Hope.

He had always been interested in the old navigational methods used to explore and populate the Pacific, and used what was then known by Europeans of these techniques to make the Tahiti-New Zealand leg of the voyage without using a compass, sextant or chronometer.

Back in England, after completing the first circumnavigation by a multihull, Lewis sold the REHU MOANA and in 1967 bought ISBJORN, a ketch-rigged fishing boat. With a research grant from the Australian National University and with Fiona, two daughters and 19-year-old son, Barry, as crew, he set out for the Pacific again to study traditional navigation techniques.

For 200 years sailors from the Atlantic hemisphere, amazed at the Pacific peoples' ability to find their way across their vast ocean, had dreamed up ingenious theories to explain it, but Lewis tackled the problem differently. He went to a Micronesian island whose sailors were known to make voyages in their canoes without modern instruments, and in due course he was invited to a meeting of elders, where he was asked, "What is your name, where are you from, and why are you here?"

His iron will and stubborn persistence were always masked by a humble, apologetic manner - he was, indeed, "the mildest-mannered man who e'er cut throats" - and he quietly replied: "My name is David Lewis, I come from the village of London in the island of England, and I have come to sit at the feet of your wise men and to learn how to find my way across the sea."

They recognised him as one of their own, took him on their canoe voyages and taught him their navigational lore. Their navigation skills had never been lost but had been in continuous use up to the present day, unrecognised by Europeans.

In ISBJORN they accompanied him to islands further afield, where he met and learned from other native navigators. Their navigation depended on a memorised nautical almanac referring to many more stars than our own. They used only vertical and horizontal observations and therefore did not need a sextant, and for a compass they used their almanac of "amplitudes" for the rising and setting of stars.

Lewis recorded all this in his research thesis, and in his books We, the Navigators and The Voyaging Stars.

Others began to study under the native navigators. The arts of canoe building and voyaging, which had died out in many parts of the Pacific, were revived, and Lewis earned respect as an anthropologist.

He still hankered after another, bigger sailing adventure. His dream was of circumnavigating the Antarctic continent single-handed, which he planned to do in ISBJORN.

His son Barry prepared to bring her to Sydney. ISBJORN, after several years in tropical waters, was in a bad way and foundered in a storm, uninsured. Barry was unable to save her after a watertight bulkhead failed, but the crew was unharmed. Lewis, without a ship or money, managed to get a small steel yacht, which he renamed ICE BIRD, and prepared her for the voyage in desperate haste.

ICE BIRD was given to capsizing in big seas, and did this in the high latitudes, losing her rig and damaging the cabin side. Nothing was heard from Lewis for 13 weeks but, against all probability, frostbitten and exhausted, he brought her into Palmer Base on the Antarctic Peninsula under a jury rig. There she was repaired, and he set out to complete the voyage, but was capsized again. This time he brought her into Cape Town and handed her over to Barry, who took her back to Sydney while Lewis wrote ICE BIRD - which became a bestseller and was translated into many languages.

Like Fred Hollows and some other New Zealand medical students who had grown up in the Depression years, Lewis became a communist. He was opposed, not to capitalism alone, but to any ruling system whose bureaucracy victimised the underdog - he was equally critical of British colonial government in Jamaica and of Russian government in east Siberia.

In his Antarctic voyage he found that the governments which had claimed sectors of the Antarctic were bitterly opposed to anybody, even their own nationals, entering the territory at all.

After that voyage, his next project was to get private expeditions into the Antarctic despite the bureaucrats, and we were treated to the wonderful spectacle of a communist successfully leading a private enterprise against entrenched government.

In Australia in 1975 he began to set up the Oceanic Research Foundation with the object of sending private expeditions to the Antarctic. Cunningly, he used the same tired old pretext of scientific research with which the governments justified their occupation of the territory, to justify his own irruption into it.

Fellow adventurer Dick Smith immediately saw the value of Lewis's enterprise and helped him with organisation and finance, and soon he had the ocean racer SOLO with a crew of eight on their way to the Ross Sea.

After this successful start, SOLO was replaced by the converted fishing vessel Tunny, renamed Dick Smith Explorer. In her, Lewis made a summer expedition to Commonwealth Bay and wintered over in Prydz Bay, in the Australian sector.

Crews of up to 12 were sailing with him, but Lewis was almost as unfortunate with them as Jason was in crewing the Argo. Some set the ship on fire, wrecked the machinery, sent out bogus distress calls, steered a reciprocal course, mutinied and even tried to kill him. Lewis never left anyone in doubt as to who was the captain, and dealt with these difficulties with a firm hand.

The many small craft he sailed were another continuing worry. It has been said that no ship ever left port that was in all respects ready for sea, but Lewis's were less ready than most.

The very nature of his projects required him to prepare for voyages in great haste and short of funds. In his own words, "problems that were not solved were pushed aside". It therefore came as no surprise when CARDINAL VERTUE broke her mast at the start of the 1960 trans-Atlantic single-handed race, REHU MOANA's rig fell down on her maiden voyage, ISBJORN foundered before the first Antarctic voyage, thereby undoubtedly saving Lewis's life, Ice Bird capsized repeatedly, DICK SMITH EXPLORER was rolled twice in the Ross Sea, CYRANO sailed better sideways than forwards and put Lewis in hospital with stomach ulcers, and TANIWAH broke her foremast on her first voyage and sank.

Lewis always brought his crews home intact. He was a typical Polynesian sailor, getting into trouble through haste and neglect, then, with near superhuman courage and seamanship, fighting his way out of it.

He knew the right time to quit, and when he had seen the Oceanic Research Foundation through its first three Antarctic voyages, and others were following through the breaches he had made in the bureaucratic defences, he left to continue his researches into traditional navigation among the Inuit on both sides of Bering Strait. With this completed, he retired to New Zealand to write his autobiography, Shapes on the Wind.

By this time his many achievements had been recognised by the academic, adventure, sailing and anthropological worlds, and he was made a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

In the second edition of Shapes on the Wind, he tells how he returned to Australia after the loss of TANIWAH in New Zealand and got himself a small cheap yacht with the help of Dick Smith.

Smith writes:

"David Lewis was the most wonderfully fantastic scallywag I have ever met. His love for the ocean can only be balanced by the love of beautiful women for him.

"His ability to charm people, not only myself but many others, into raising the funds for his many adventures should be an example for all young people who want to follow in his footsteps."

Lewis fitted out LEANDER and travelled quietly up the Australian east coast, with his eyesight failing, until, at Tin Can Bay, he became blind. From there, with the help of friends, he continued cruising to Rockhampton and among the Keppel Isles, then returned to Tin Can Bay, where he died, aged 85.

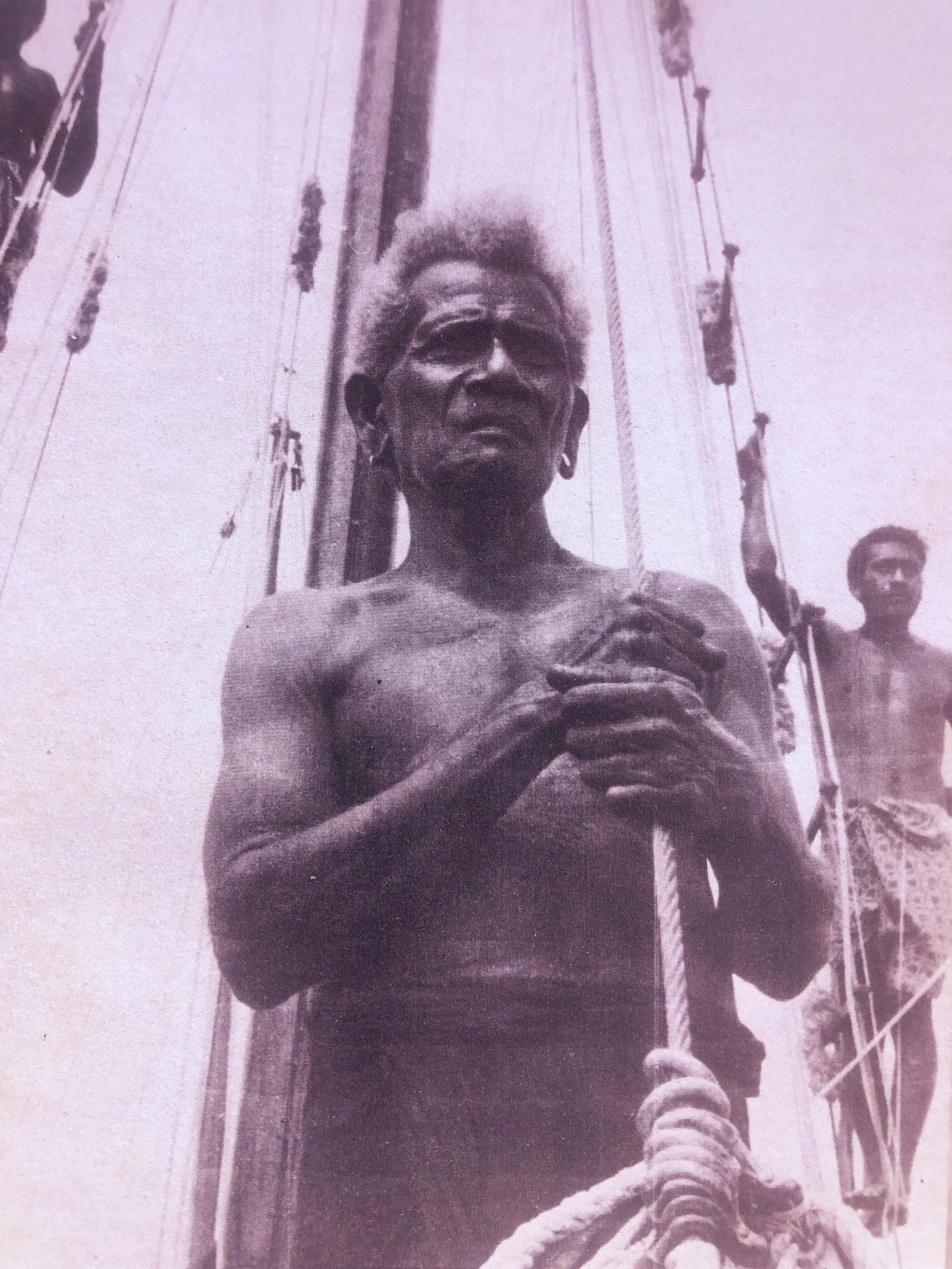

The book “We the Navigators” arose from Lewis’ decision to test his understanding of Polynesian navigation techniques by sailing the 2200 miles from Tahiti to New Zealand without any modern instruments (except the smallest of charts and a sky map). After arriving with a landfall only 26 miles in error, he learned that there were contemporary sailors in the Santa Cruz and Caroline Islands who still sailed large distances by the traditional methods and obtained support from the Australian National University to visit and sail with them. He did this in a 39-foot gaff ketch, ISBJORN, which he placed under the direction of the navigators Tevake and Hipour.

Tevake conning ISBJORN between the coral heads of Nufilole Lagoon.

These navigators spoke very little English, were illiterate and did not understand maps but were able to take him eventually on a 450-mile trip from Puluwat to Saipan and to return and teach him many of their techniques.

There is so much to admire about David Lewis but is his ability to combine “boys own” action with deep intuitive thinking is what makes him special. He was no academic, theorising from an ivory tower, nor was he an unthinking thrill seeker. I wish I had met him. Hopefully his work will continue to inspire people like me for at least another 50 years.