Well Written - Part II

In this second part of our series on underrated maritime texts, we visit one of my favourite accounts of racing, rather than cruising wooden boats across oceans.

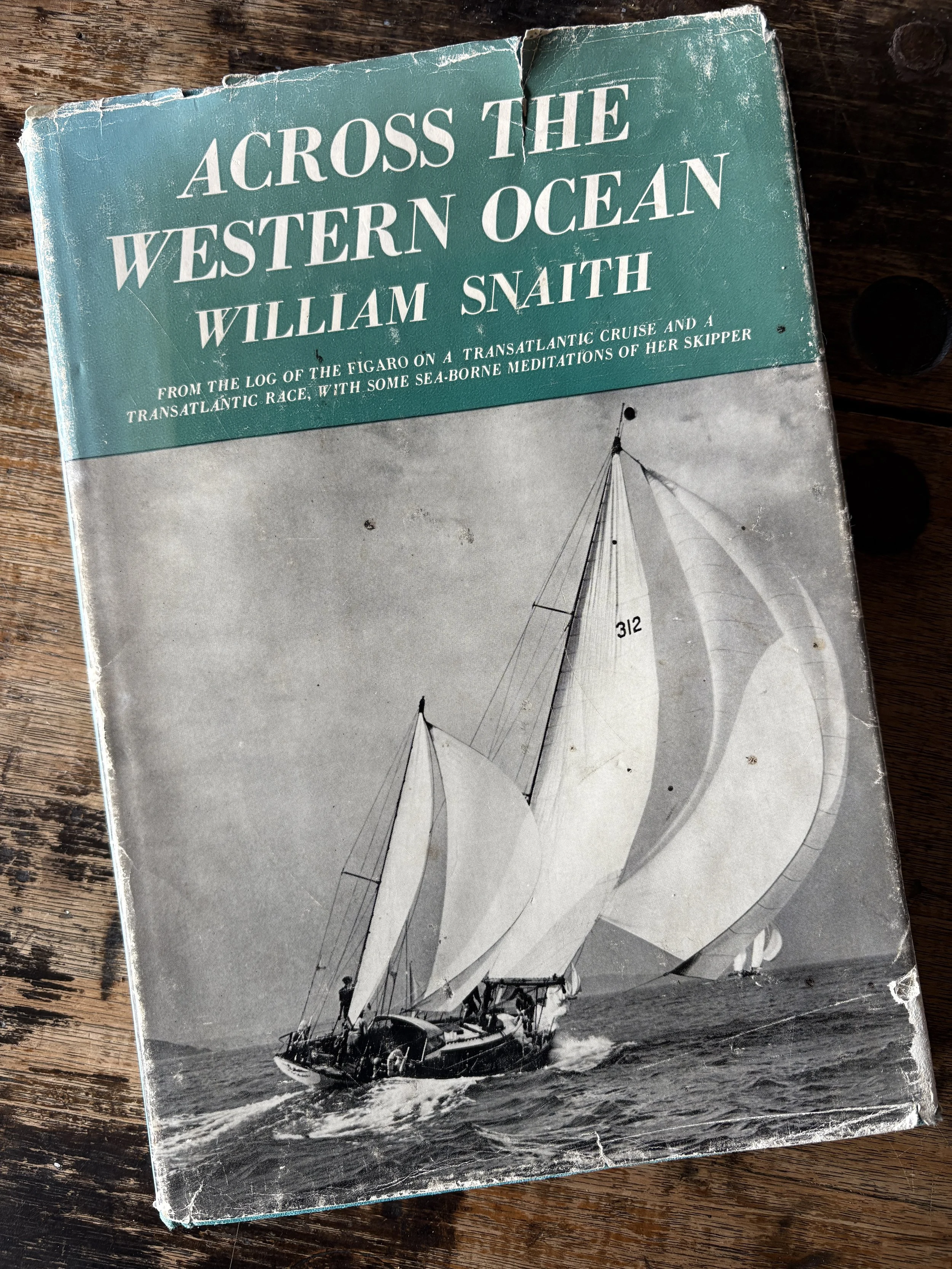

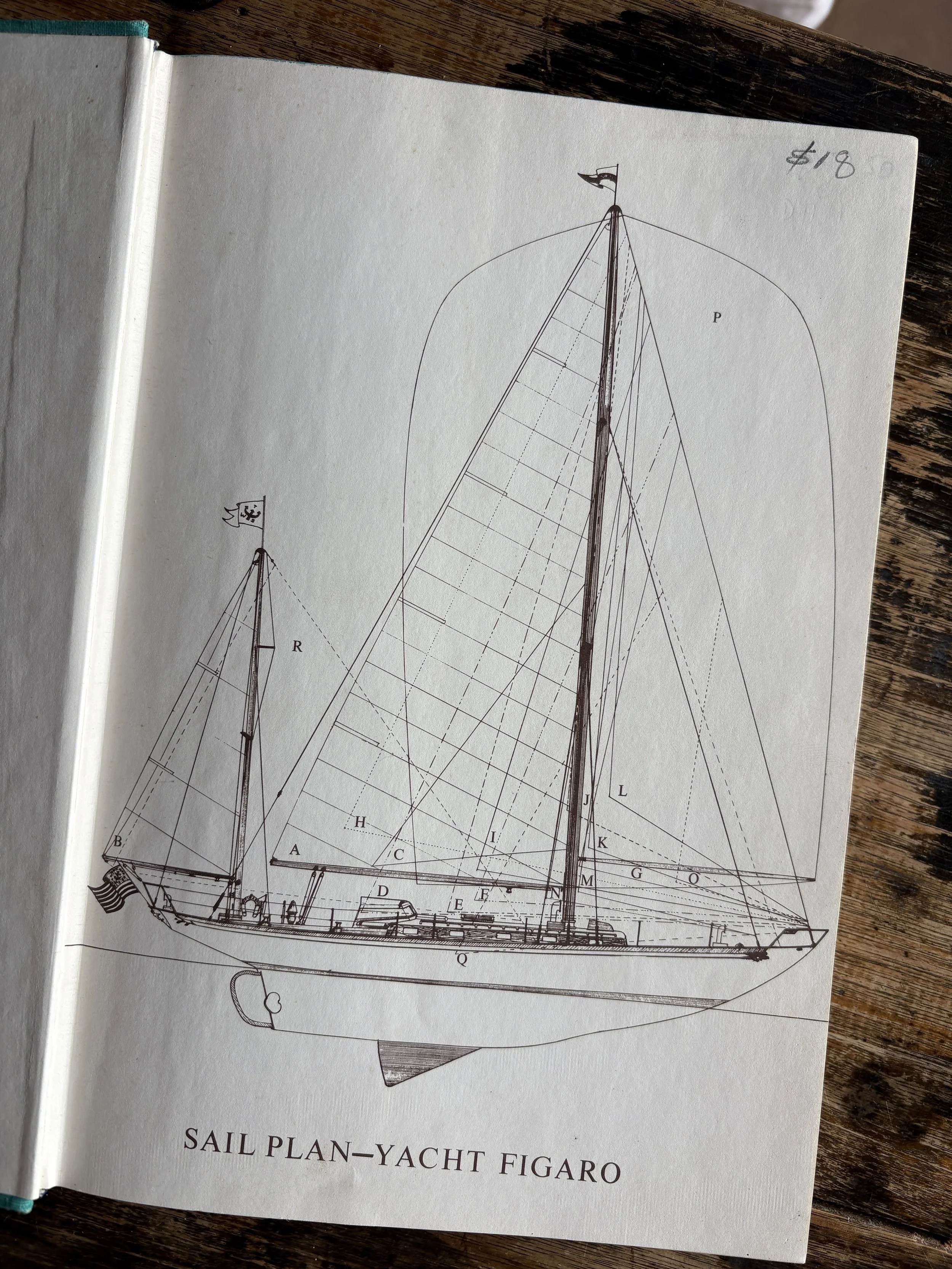

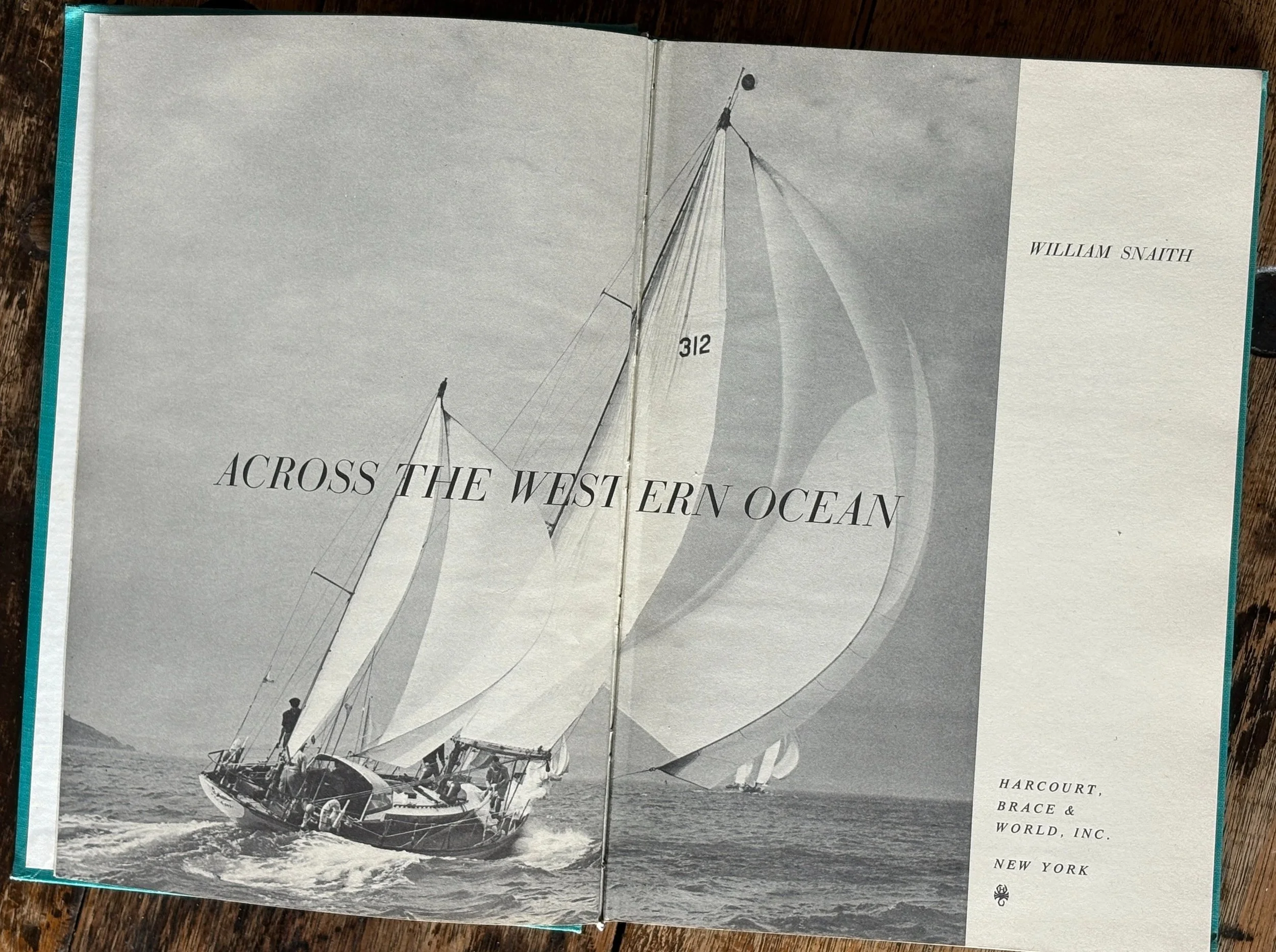

William Snaith builds his book , “Across the Western Ocean” around the log of the centre board yawl FIGARO as she races across the Atlantic in 1961. He writes so beautifully, with the confidence of another era. I feel and smell and hear every nuance in the script. Over two decades, Snaith owned and captained a series of yachts of the same name, achieving significant success in competitive sailing, including winning the 1965 Southern Ocean Racing Conference series and participating in the 1967 Admiral’s Cup in England. But I would argue that his most important legacy is in the two books he left us. “Across the Western Ocean” (1966) & “On the Wind’s Way” (1973). The Passage below is from the opening Chapter of the former.

Just imagine yourself, one dark night, on board a 47-foot centerboard yawl, banging into a head sea somewhere south of Fastnet Rock in the southern approaches to Ireland.

You are there, working out your watch on deck. You sit, wet and weary, thinking only of your approaching turn in the sack. Trickles of salt water thrust impudent icy fingers between your oilies and your neck and armpit. You are locked into your misery, holding fast to the remaining glimmer of the only true happiness your feet are still warm and dry. Then that unfeeling bastard, the skipper, thinks it's time to change jibs. So you go forward, get new-wet to the navel, fill your boots, and with eyes stinging with salt you come gasping back to the cockpit.

"She feels better," he says. "Balls," you think and, man, the time has come when you have joined a gallant company. You are with Ulysses at Scylla and Charybdis, Leif Ericson in the Davis Strait, and Magellan in straits of his own. They, too, at one time or another, must have asked themselves: "What am I doing out here?"

That's the question each sailor answers for himself. You do not even have to be on deck for the question to arise. The sanctuary below decks is such only by comparison. Try sleeping inside a bass drum while the band is playing the "1812 Overture." That's what that little wooden island sounds like as she shoots off the top of a long green wave and falls into the hollow at the back side. You swear you can hear the heel of the mast grinding through the mast step. You pulse with each whack of the centerboard as it bangs from side to side in the trunk. With the disengagement of a somnambulist, you wonder how long this marvelous arrangement of wood, bronze, stainless-steel wire, and dacron can hold together. But, like Scarlett O'Hara, you'll think about that tomorrow.

Your bunk is no retreat. You are a vagrant chunk of ice in a cocktail shaker. You hold on to the berth with your toes and the muscles of your derriere, all the time scrounging out of the way of the Chinese torture-drop coming off the over-head. (Damn that shipyard man, you told him about that leak.) You don't feel like eating, but that damned fool Cookie (showing off) has fired up the alcohol stove. The cabin slowly fills with unconsumed alcohol fumes which make your eyes smart and which go right to the pit of your stomach before his miserable scrambled egg can get there. My friend, you are ocean sailing: which, as a sport, can provide more concentrated discomfort than anything—short of bronco riding—and what it loses in vehemence, it makes up for in duration.

And still, the Corinthians fight for a berth on a yacht going to sea. They can’t all be masochists. There must be something more than that. Despite the opinion held in some quarters that anyone who would go to sea for a pastime would go to hell for his pleasure, the men who go out in small boats show more or less rational attitudes to most other aspects of living. There must be a reason for such an unseasonable madness.

And so there is, but to each his own. To one, it is the kinetic loveliness of a sailboat working its way through the seas. To another, it is the challenge of the unruly elements. To one man it may be the competitive zest of a race, while to his shipmate it could be the landfall after days at sea. To my late friend Judge Curtis Bok, it was the sea itself, “which has no memory and shows no compassion and which shows an indifference so vast as to make man go silent in its presence.” To all, it is a unifying love for the sea, the love of ships and the wonders of things nautical—natural, man-created, and historical. They are part of a new and growing fellowship of the sea—those who go out upon the ocean in small boats for the enjoyment of this peculiar form of pleasure.

Now imagine yourself in another time and setting. You are in the snug saloon of a straight-stemmed, black-hulled P & O steamer, black coal smoke pouring from her high stacks as she plows down the Bay of Biscay. You are in the company of narrators of another generation. In the Victorian snuggerly of the cabin are the artifacts of a statelier tradition and on every hand the signs of good shipkeeping can be seen. A sea-coal fire burns in the grate. The oil lamps, which fill the cabin with a soft golden light, burn steady in their gimbals; the lamp trimmer has done a conscientious job. Dinner over, the table cleared, and Sumatra cigars aglow, the claret bottle is passing from hand to hand. The mahogany table, rubbed up like a mirror, gleams with crystal and ruby reflections. It is a warm and friendly atmosphere.

It is also time for ruminative talk. For in this imagined setting are men who have earned the right to a backward appraisal. Among them are Joseph Conrad and Marlow, his creation, observer and commentator on human events. It is Marlow who is speaking. His story is told in “Youth”—how, at the age of twenty, he set sail for Bangkok, going as second in the aging barque JUDEA OF LONDON. In speaking for the writer of the sea and of men, he holds a contrary opinion as to the make-up of the fellowship of those who follow the sea, for he says: “There is a fellowship of the craft which no amount of enthusiasm for yachting, cruising and so on can give, since one is the amusement of life and the other is life itself.”

Well, life itself has become unlike anything that Marlow or the others in that cabin could have imagined. They may have had justification for that opinion then, but now a deck officer distributes his skill between handling the dissident shop steward from a seamen’s union and meeting the rigors of an unfriendly sea in a ship equipped with automatic gyro steering and anti-roll equipment. Now that the voyage to and from ports of call in such a streamlined container of mechanical marvels normally is as eventful as bringing the 8:10 A.M. daily commuter safely from Westport, Connecticut to New York City, I wonder if the fellowship of the craft does not lie with the other side.

Yachtsmen probably are the only supporters left in this Western world of that lovely old relic of the past, the sailing ship. With the exception of a few official sail training ships, the age of the lofty windjammers is gone. Today, the wind sailor goes to sea in a small sailing boat which, as a sport and a means of transportation, has been called the most vexing, expensive, slow, and frustrating means of getting from one unimportant place to another. And yet, men keep going out in these small boats for the sheer joy of sailing—a joy which mysteriously hovers between rapture and misery. They sail to enjoy active physical discomforts, loss of privacy, and most of the cherished props to one’s amour-propre. Yet these are the very same men who, while on land, will complain if the toast is cold, or if there are insufficient towels in the bathroom, or if the headwaiter keeps avoiding their eye.

But at sea, and especially at the start of a long ocean race, they set out for their inevitable share of misery with foreknowledge of trials to come, but with spirit expanded and with wide-eyed contentment. It is a test of one who has found the way. For, despite all the discomforts to do, there will come great pleasures—pleasures in their own skills at a time when individual skills are disappearing into a mass, man-automated complex; a sense of victory in contest with powerful elementals; and the companionship of their fellows in the midst of a shared adventure. Surely, Marlow and Conrad notwithstanding, the great fellowship of the craft now must be with the yachtsman and cruiser.

I suppose that an important part of what makes it life itself for the professional is economics. He earns his living that way. In addition to the mysterious compulsion of the sea, he is motivated by the pragmatic compulsion of economic necessity. But for the yachtsman, there is an obverse side to that coin. Considerable economic sacrifice is made to indulge the passion for sailing. Far from being a means of earning a living, it is rather a costly indulgence. A fellow I know says ocean racing is like standing in an icy shower while tearing up $1000 bills. That’s one owner’s description of the price for fun in a specialized form of discomfort. But consider the Corinthians who sail with him. There is nothing more apt to defeat a schedule than a long yacht race. A race may start on Friday night at 1830 hours, but it can finish on Sunday or Tuesday—the gods of wind and wave willing. The Corinthian must be prepared to defend his loss of time on the job to a boss whose enthusiasm may be golf or his business, or have so ravishing a story to tell that his absence is glossed over.

And then there are social pressures. For instance, there is the married fellow whose wife was sympathetic and understood his passion for the sea in the first years of marriage. Now that sympathy and understanding is eroding with time.

An ocean-racing sailor is absent from home and hearth on occasions when all other families are practicing togetherness. A real affront to any reasonable marriage.

What of the miseries? They are real enough. And yet the ocean-racing buff and his fellows keep going; he sea-happily, ardently, and in ever-growing numbers. Each of the fraternity that follows right reason for his enthusiasm and shares a bit of the other man is not to be confused with the business of living.

The pleasures and adventures of deep-sea racing are separate and treasured by each man who sails. They are kept on file in one regard—while it’s a way against water there is no sailing at hand. One form of memory bank—to be drawn on as needed—is the ship’s log, an active record of happenings. The sailor’s compulsion to tell yarns is as old as sailing itself. The sailor’s compulsion to tell yarns is essentially a love story, the story of his love.

The full copy of “Across the Western Ocean” is available for free ONLINE