A Certain Kind of Magic.

There are some sailing passages that stand out in memory for being perfect; when the wind is abaft the beam all the way, and never gets above 20 knots, the sun shines day after day, and the sea is less than two metres, with a long, easy, wavelength.

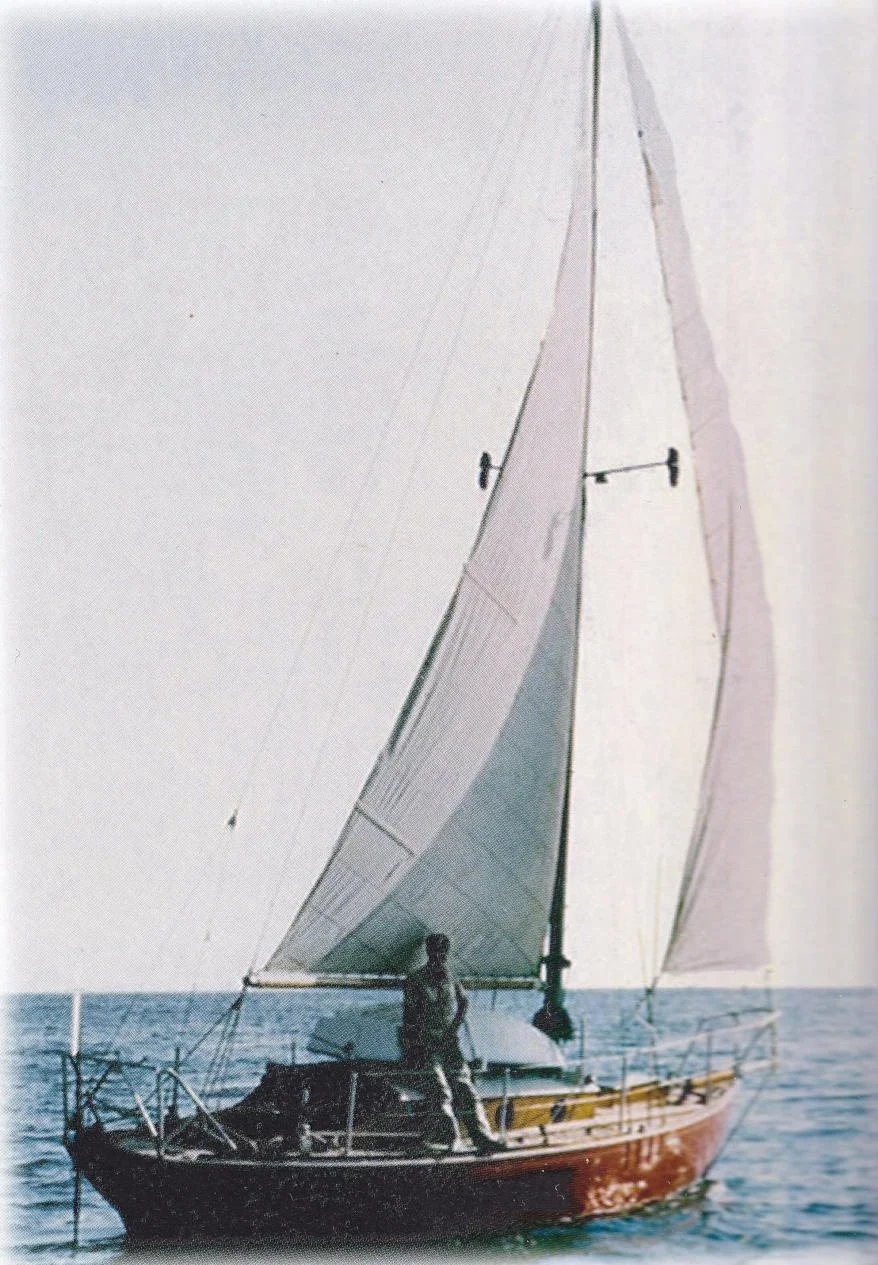

Tarmin under sail

When all these factors align, it is pure sailing magic. However, the concept of sailing magic took on another twist for me in November 1969, when John Sowden sailed into Durban on his Robert Clark five-tonner, Tarmin. The following story is adapted from my two-volume sailing memoir, Last Days of the Slocum Era:

It was always the small boats under 30ft that excited me the most as a boy on the International Jetty in Durban, South Africa, and they still do. I was standing on the jetty one day when a small, red sloop sailed in. John Sowden, sailing singlehanded on his 25’ Tarmin, was 21 days out of Mauritius. He looked as fresh and relaxed as if he had just been out for an afternoon sail.

An American, he'd lived in Spain for a number of years, after working in many countries during his career, and was something of a magician, having performed on stage in Sydney shortly after World War Two. John was 49 years old, but still had a youthful demeanour, and an excellent, casual dress code. Occasionally, at parties, he could be induced to demonstrate a few magic tricks, such as losing his cigarette, and then, after looking for it everywhere, and asking everybody around him to look for it also, to the consternation of the skipper whose deck he was standing on, taking it out of his mouth.

Magic was just a hobby, though there was a playful quality in everything John did. Many years later, I discovered that he’d recently retired from an international career installing radar systems for Radio Corporation America (RCA). Perhaps having such an intimate knowledge of complex electronics influenced his decision to voyage in the smallest, simplest boat imaginable. Apart from a wind-driven self-steering mechanism, Tarmin was entirely devoid of special equipment. John didn't even have a spray dodger over the main hatch, or an awning. Later, he hand-stitched himself an awning. When his unreliable petrol engine wasn’t working, he did not have electricity aboard.

He bought the carvel-planked Tarmin, a Yachting World 5-Tonner designed by English designer, Robert Clark, in Mallorca in 1966. The boat had been built in 1949 in England and was registered in London. It was in a decrepit state when he bought it, and he saw it as a winter project, not intending to do any serious sailing. But after patching up the old boat, he'd drifted from Spain to the Canary Islands, thinking the climate there might be more congenial for working outdoors in winter. In the Canary Islands, he realised it was easier to sail on to the West Indies than beat back against the prevailing winds to Europe.

‘After that,’ he said, ‘it just made sense to keep going.’ Now here he was in Durban, still working on the boat. It may have been decrepit once, but he kept it immaculate now. Its bright red hull gleamed, its mild-steel metal fittings were painted silver, and he was always working on something or other.

Tarmin on Wilson's Slipway, Durban, in December 1969

The only thing that seemed to defeat him was the 8hp, hand-cranked, Stuart-Turner petrol engine, perhaps because it lived under the non-self-draining cockpit that emptied into the bilge. John covered the engine with a sheet of plastic when at sea, or an old mackintosh. Numerous attempts had failed to keep the motor running, and for much of the 20 years that John roamed the oceans, Tarmin sailed engineless.

‘You don't need one for this sort of sailing,’ he said, ‘though it takes some of the worry out of entering and leaving port.’

He was quite conservative with money, which probably accounted to some extent for his becoming financially independent by his mid-forties (the other factor being that RCA paid his wages into an American bank account, on which he did not have to pay income tax, since he worked abroad. His father, a banker, invested it for him.) As a result of his fiscal caution, he stuck with the wonky petrol engine when he could quite easily have installed a small diesel motor, and he patched and resewed his sails until they were beyond salvation. He also stuck with his inadequate Quartermaster windvane self-steering unit, despite repeatedly bending the shaft of the trim-tab (servo rudder) in boisterous conditions.

I looked askance at the large, open (non-self-draining) cockpit. ‘What happens when waves break into it?’ I asked.

‘Oh,’ said John with a quiet smile, ‘the water just goes into the bilges and I pump it out again. It's safer than having all that water trapped at the back of the boat when the next wave rears its ugly head. Besides, it keeps the bilges clean.’

He had a calm, simple approach to seamanship. He never entered port at night, preferring to heave-to offshore under triple-reefed mainsail and wait for daylight. Patience, he said, was a seaman’s greatest virtue. In heavy weather, he would either heave to under triple-reefed mainsail, or, if conditions got too bad, or the gale was going his way, he ran off, initially under bare poles, then with the storm jib sheeted flat fore and aft.

Tarmin alongside the International Jetty in Durban in December 1969.

‘Are you going to write a book?’, I asked. ‘I couldn't,’ he said, ‘there would be nothing to put in it. Nothing ever happens to me.’

On the passage from Durban around the Cape of Good Hope, a ferocious SE storm sprang upon the ship as they approached Table Bay, just a few miles short of Cape Town harbour. John had already poured himself a congratulatory glass of whisky. He ran Tarmin off downwind, NW into the Atlantic, with the storm jib sheeted flat, fore and aft, and every spare rope in the boat, plus the bosun's chair, streaming out behind. The wind blew at over 100 knots, verified by the Cape Town Weather Bureau, for 18 hours.

Unable to keep his oil lamps burning, he lashed an electric torch to the rail, illuminating the sail, and hoped for the best. Tarmin was in one of the busiest shipping channels in the world, and visibility was almost zero. Then he went to bed and slept through the night, as best he could amidst the howling cacophony. He said the sound of the tightly-sheeted jib backwinding was frightening, and every time it did, the rig shook violently, with the vibration being felt throughout the boat. When he woke, he found 200mm of water slopping over the cabin sole. It took him a week to beat back to Cape Town.

Tarmin and John Sowden in Durban shortly after arriving from Mauritius, November 1969.

But he still didn’t write a book. He was one of the happiest lone sailors I ever met, seemingly content with his own company. He claimed to be a natural-born loner, yet was always willing to share a joke or a cup of tea when the occasion presented itself. Between 1966 and 1986, he sailed Tarmin three times around the world alone, earning himself a place in the Guinness Book of Records, which pleased him, but he had no desire to seek further recognition. He sailed for his own satisfaction.

Tarmin made a number of very long passages, twice being at sea for 90 days or more, once from St Lucia in the Caribbean to Recife in Brazil, en route to Rio de Janeiro, and once from Panama to San Diego, beating against prevailing wind and currents on both passages. Both are considered notoriously difficult for small, engineless craft.

Tarmin in St Lucia West Indies, the day after arriving non-stop from Durban, apart from a short stay in St Helena Island, at the end of John Sowden's third circumnavigation, 1986.

Tarmin and John Sowden in St Lucia after his third circumnavigation.

On the trip down to Brazil, with Tarmin pitching into steep head seas, John fell while changing his hanked-on headsails on the foredeck, landing on the pulpit and breaking a rib. For some weeks he had to sleep sitting up, wedged in a corner of the leeward bunk, until his ribs healed.

He chose not to stop in Cape Town during his second and third circumnavigations, sailing non-stop from Durban to St. Helena Island, which has a very exposed anchorage where rest is impossible, then on to the Caribbean. Cape Town Harbour, as many voyagers have found, was very dirty in those days, with crude oil in the harbour soiling lines and topsides, plus black soot on deck from the steam locomotives that shunted back and forth behind the yacht club. Once was enough for John.

By the end of his third circumnavigation, iron-fastened Tarmin was becoming very tired. He’d repaired serious rot in the bows, and there were numerous leaks that soaked everything below when the decks were wet. He repainted the hull white for this last voyage, hoping the cooler colour would be kinder to the aging carvel planks.

I remember, during his second circumnavigation, as he worked his way through the reef-strewn waters of the Torres Strait under sail, with the engine defunct, as so often, how he marvelled at the boat’s performance, and wished somebody would make a fibreglass version. He was so enthralled with that boat. Tarmin was almost 30 years old by then, and it is astonishing that he went on to complete a third world voyage. He sailed non-stop, engineless and solo, through the Torres Strait three times, possibly a record in itself.

John Sowden died from bowel cancer in 1990, four years after the end of his last circumnavigation, and just short of his 70th birthday. His calm and courageous approach to seamanship has remained a standard-bearer for me all my adult life. His story has been recorded for history by his youngest sister, Joan Sowden Deily, in her book, Alone on the Sea, compiled from John's extensive logs, tape recordings and letters.

John Sowden, filling his water bottles in Durban, December 1969.

Graham Cox has been appointed as guest race commentator for the McIntyre Mini Globe Race (MGR), https://minigloberace.com/ and his memoir, Last Days of the Slocum Era, is available as a paperback book from Amazon, or as an ebook from Amazon or Kobo.