A NEW MAST FOR VANITY

by John Crawford

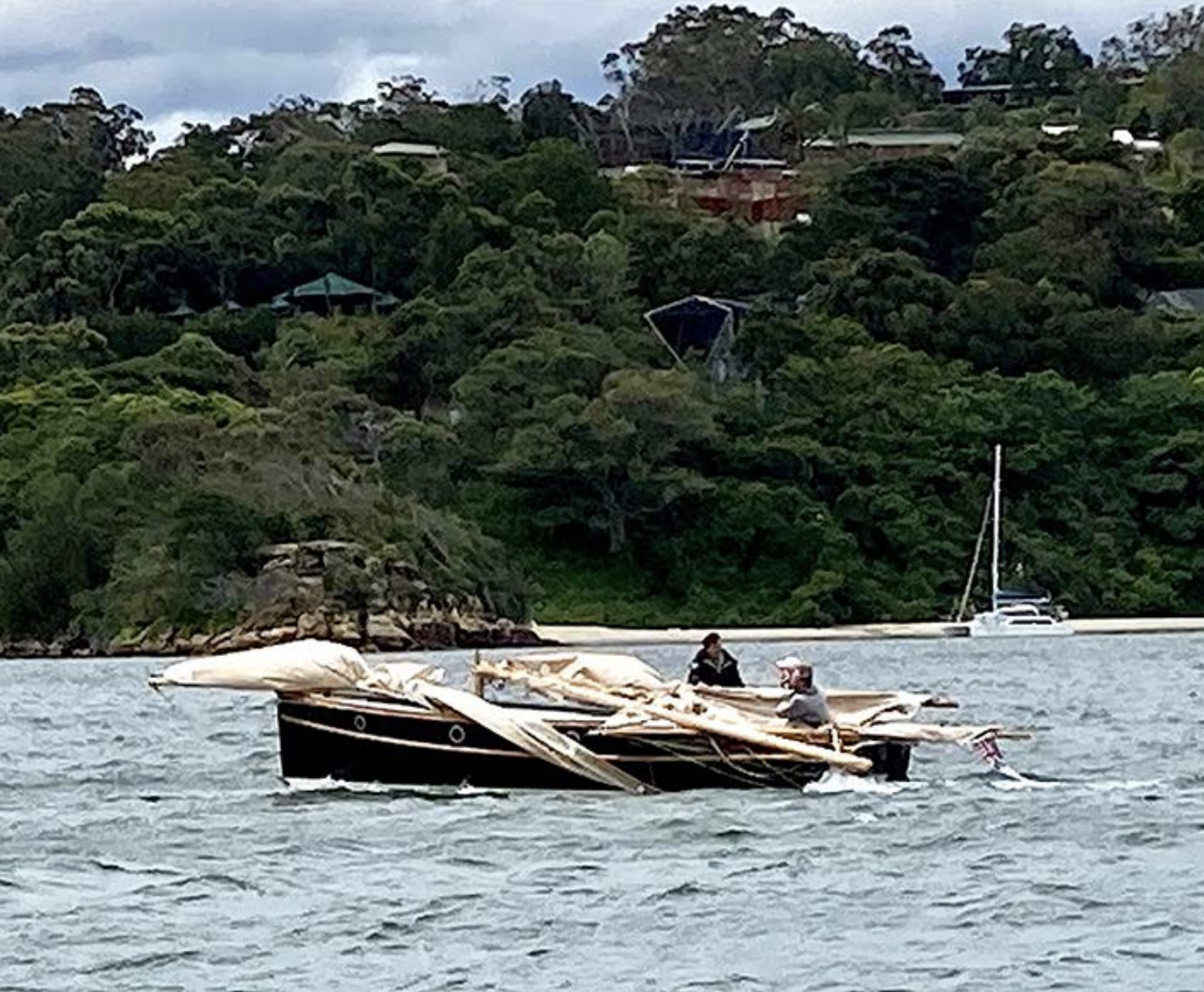

A tragic sight — VANITY on the way home

Those of you who were early adopters of SWS might remember this gem of an article published in March 2021. Well, John Crawford, one of our most articulate and informative contributers, is back with a new story, this time from the Newsletter of the famous Sydney Amateur Sailing Club. We were sorry to hear about VANITY’s dismasting, but the silver lining is that we can now learn how to approach such a setback.

We hadn’t sailed for a while. Covid had disrupted our sailing enjoyment. It didn’t make for convivial gatherings after races and many people, myself included, felt disinclined to go to the club that for years has been a place of such pleasure, relaxation and almost selfish secret enjoyment. The crew of VANITY needed a sailing fix and Race 3 of the Commodore’s Cup on November 13 was to be our antidote. The forecast was not promising — a gusty nor’west to west wind boxing the compass while it decided which direction it really wanted to punish. Initially it was not that strong, so the crew, Peter McCorquodale, Liam Timms and your scribe, decided that a full main and a Number 3 would be comfortable.

In more than 20 years of racing VANITY we have only reefed about half a dozen times. Race Management on CAPTAIN AMORA had decided on Course B, starting at Shark Island heading under the Bridge and up and around Cockatoo Island, then back to a Kurraba Point finish. Going ‘up the River’ would also provide better protection from the increasingly strong wind, gusting to 25 knots plus. Our sailing was becoming more about survival as we crossed the line. Boats ahead were forced east toward the moored boats off Point Piper so we decided to tack out toward Bradleys Head. But we didn’t get very far because the wind and waves off Bradleys looked unpleasant.

Hydrodynamically, Rangers — shaped like a fruit box — don’t enjoy waves. We tacked back heading for the more sheltered lee of Clarke Island. Vanity had settled down and was going quite well. Our confidence was short lived. A nasty wayward gust laid her over to port and as she recovered the boat seemed to sigh slightly. The mast above the cross trees decided it had had enough and broke off. With no upper shrouds, the rest of the mast soon followed suit with a resounding crack leaving a two-foot stub above the deck — and that was that! No one was hurt, and no damage was done to the hull or the sails and rigging. We had adequate sea room so the broken spars were pulled aboard and tied down.

Commodore Sean Kelly, who was manning the Fast Tender, came out to make sure we got back safely. Thank you Sean.

The broken mast at the spreaders

And at the deck

Why had the mast failed? There were a number of factors: age, the gusty conditions, the mainsail hauled on too hard and too much tension in the peak halyard. There were some signs of soft timber at and aroundthe spreaders, but this was not really apparent from the outside. The failed mast was hollow, built from eight epoxy-laminated Oregon strips with solid timber cylindrical sections glued in place at points of stress such as the spreaders, the halyard winches, gooseneck, jamb cleats, spinnaker rings etc. An internal electrical conduit served the mast top navigation lights and possibly this is where rainwater found its way into the hollow core and settled on the first piece of ‘timber blocking’ at the spreaders, thereby contributing to the decay of the mast from the inside. The lower shrouds terminate just below the spreaders in a sleeved ‘through mast’ bolt, which might also have contributed to rain water finding a way through. Who knows? Whatever the cause, the next step was working out how to get a new timber mast.

I approached my insurance brokers with some trepidation, described the event, provided photos and answered all their questions. After a long delay (and some prompting) we learned that the insurer had decided to appoint a loss adjuster to inspect the mast. By this time I had decided to get on with it. I explained to my broker that timber masts were bespoke items, not available over the counter at Bunnings, and needed not only the finest timber money can buy, but also a shipwright with the requisite skills. In the mean time I removed the broken spars from Vanity, purchased four lengths of fine-grain Douglas Fir (Oregon), secured the services of one of Sydney’s best shipwrights (the appropriately named Rick Wood) and, thanks to the generosity of the Board, arranged to utilise a long narrow space at the rear of the Green Shed to construct a new mast.

Despite my fears, the Loss Adjustor appointed by the insurer was a delight. He understood my concerns about the need for the mast quality to be the equal of the boat. He recommended to the insurer that the claim be approved, enabling the payout and providing relief to me for having gambled on proceeding without approval. The rig was fine but had to be replaced because it was ten years old and insurers don’t like stainless steel rigs which have reached their deemed use-by date. Rick Wood was ready to start, and four 6 metre lengths of 75 mm × 150 mm fine-grained Oregon (from Anagote Timbers) were delivered to the Green Shed — at nearly $1000 a length (gulp..!). The four sticks were closely inspected for minor defects and grain direction and dressed prior to scarfing each of the two lengths together. The mast’s overall height is 10 metres from step to truck. Each scarf joint was approximately 1000 mm long.

All the dimensions of the original mast were transferred to a measuring stick, checked, and re-checked many times during the work. The mast fittings and their location on the mast were recorded and the halyard winches and jamb cleats dismantled, cleaned and reassembled ready to resume life on the new mast. Rick set up trestles at a working height and used a combination of modern and hand tools. The mast is made in two halves with the centre hollowed initially using a small circular saw blade set for varying depths followed by a hand gouge to create a perfect semi-circle over the length of the hollow sections. Once hollowed, the two halves are joined.

As the news spread that a new timber mast was being built at the Green Shed members were invited to watch a skilled shipwright fashion a traditional timber spar — something that doesn’t happen every day. The mast has three solid sections and two hollow sections. From the mast step to the gooseneck is solid, the gooseneck to spreaders length is hollow, (with a solid section at the spreaders,) then hollow again to the mast top which is solid. From the spreaders to the top the mast is tapered from approx. 135 mm diameter to around 90 mm at the masthead fitting. Below deck it also tapers from the deck-head to the mast step.

Rick Wood at work shaping the new mast

A conduit is embedded in the centre of the mast to service the Aqua Signal nav lights. Prior to glueing the two halves together the hollow sections of the mast were treated with Everdure. To achieve a perfect glue line 70 clamps were placed opposite each other along the length of the outside edges of the timber. With four people working quickly the epoxy was applied to each half and one side was lifted and flipped onto the other. The clamps were secured with only light pressure — just enough to squeeze glue from the joint line. The glue lines at the junction of the two halves and the scarf joints from either side were perfect. Pleased with ourselves, we sat down, opened some beers and watched the glue dry. Finishing the mast was quite a speedy process. The square section was quickly shaped, (4 sides to 8, 8 to 16, 16 to 32,) beginning with a circular saw, draw knife and various planes. Round sanding started using belt paper with handles at 80 grit and finished with 120 grit. Once sanded all the fittings were dry fitted to the mast and all the fixings, screws, bolts, track and winches installed prior to any varnishing. (Click to enlarge.)

Interestingly, all the screws are machine threads, which have superior holding power compared with wood screws. Every screw hole was then cleaned and filled with a thinned varnish after which the mast was given its first full coat followed by seven more. The varnish was allowed to cure after which all the mast hardware was re-installed except for the rigging and running gear which was being replaced by Noakes who would also step the mast and tune the rig.

Handle with care — manoeuvring the new mast out of the Green Shed

Loading the new mast for the trip to Berrys Bay

On the March 28 the mast was loaded onto VANITY for the trip to Berrys Bay. A day was spent rigging the new spar and on the 30th it was stepped with a $1.00 pure Silver Roo coin from the Australian Mint (thanks to Liam Timms) placed under the heel in keeping with the best seafaring traditions. Vanity then motored back to the Green Shed to have the sails and boom fitted ready for a test sail on Saturday, just in time for the Ranger Sprint Series on Sunday. We were careful to ensure that Rick Wood was aboard Vanity as part of our ‘mast warranty’ but in sometimes gusty conditions the mast performed perfectly. This was a fitting end to what was quite a long journey. Let’s hope that VANITY’s new mast lasts for at least another 20 years. In all it took 137 days from the time of the old mast failing to the new one sailing. It was an interesting and enjoyable experience. There is a great deal of satisfaction in being part of the creation of what is undoubtedly a work of art and to support craft skills which, thankfully, are still very much alive and well in 2022. My thanks go to all those who were involved and those who came to spectate. Special thanks to the Flag Officers and Board of the SASC for supporting the project and the use of the Green Shed. Also to Liam Timms for project managing the myriad details which ultimately make everything work. Finally, a big thanks to Rick Wood for demonstrating his forensic attention to detail and woodworking skills par excellence.

VANITY’s new mast was thoroughly tested on 3 April during the Ranger/Couta Sprints. Photo John Jeremy

Many Thanks to John Crawford and the SASC for allowing us to reproduce this article.