A WEEK OF VOYAGES

Here in Victoria, Australia, we are fast becoming experts in dealing with lockdowns. Version Four of our State Government’s restrictions has just been extended for another week.

It gets harder and harder to spin things positively, but let’s give it a go! It’s surely an ideal opportunity to read and dream about what travelling by boat can mean.

Over the next week I plan to post a book review each day, delving into seven of the most interesting accounts of little known maritime journeys and adventures. This is not your classic list, perhaps a little left of centre, but hopefully it will provide some inspiration on how to deal with adversity.

Book Seven (the last)

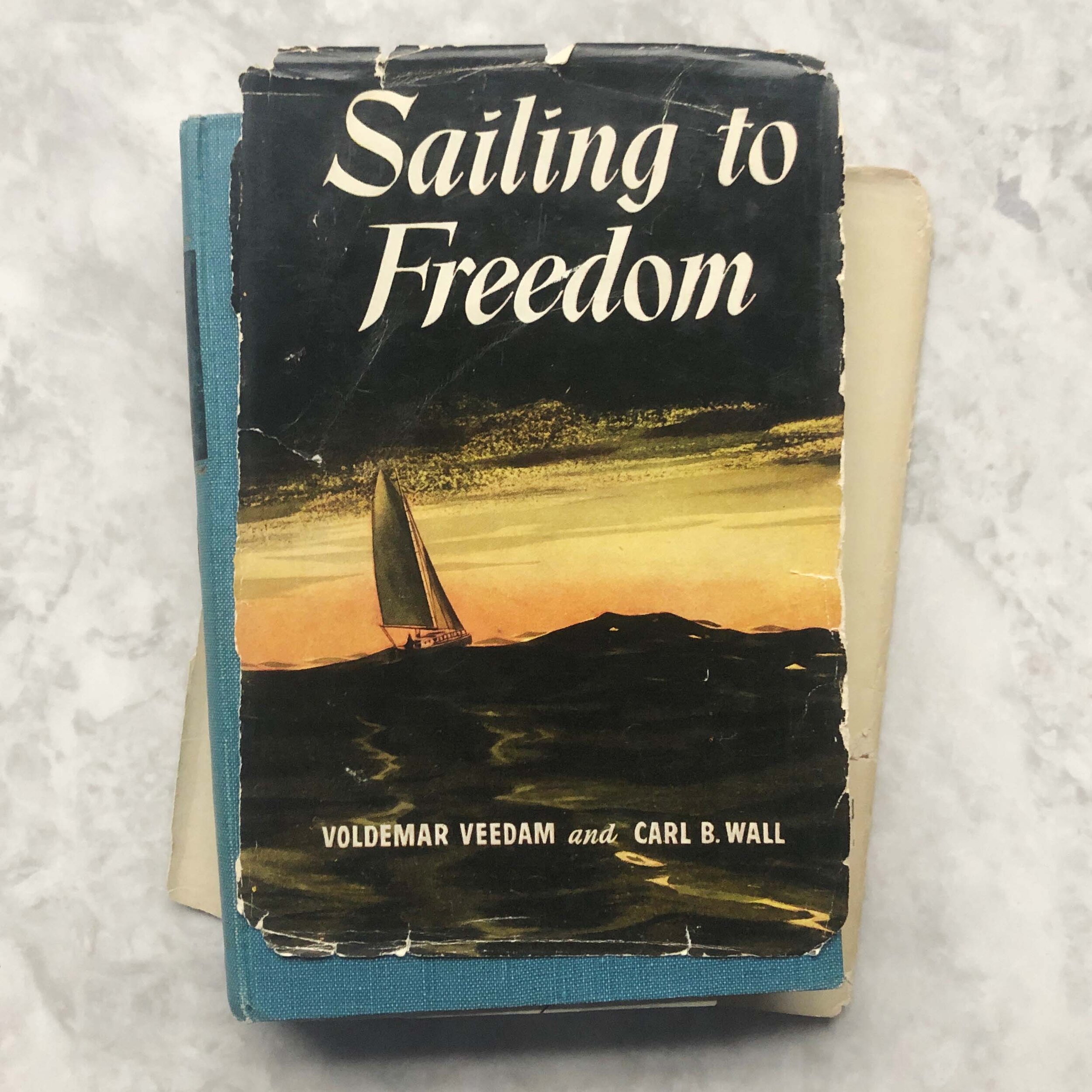

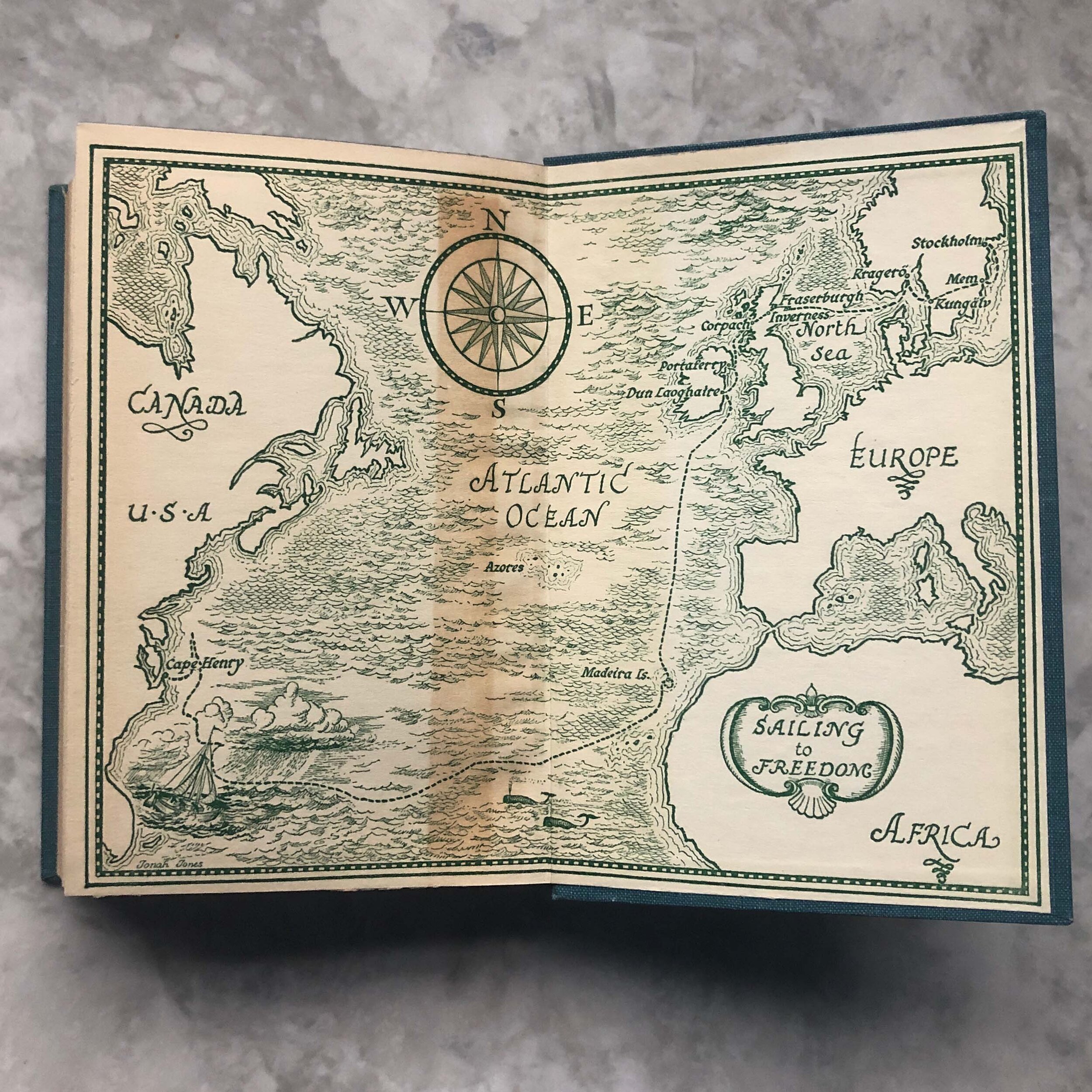

“Sailing to Freedom” – Voldemar Veedam & Carl B. Wall

It’s a story that is playing out in some form or another, every day of the year in 2021, whether it be in the Mediterranean, the Indian ocean or the Caribbean. Normal people, whose mere existence is under threat, take to a small boat, to escape to a new life.

It’s rare that a book written over 70 years ago could have so much relevance in today’s world.

This is one of the great all-time adventure stories but what makes it different to the previous six books in this column is that it’s an adventure brought on by necessity rather than free choice. It’s a story that is playing out in some form or another every day of the year in 2021, whether it be in the Mediterranean, the Indian ocean or the Caribbean. Normal people, whose mere existence is under threat, take to a small boat, to escape to a new life. This story is told in simple unembellished fashion, making their extraordinary voyage more impressive than any record breaking, publicity fuelled stunt of today.

Frank Herbert the reviewer writes…

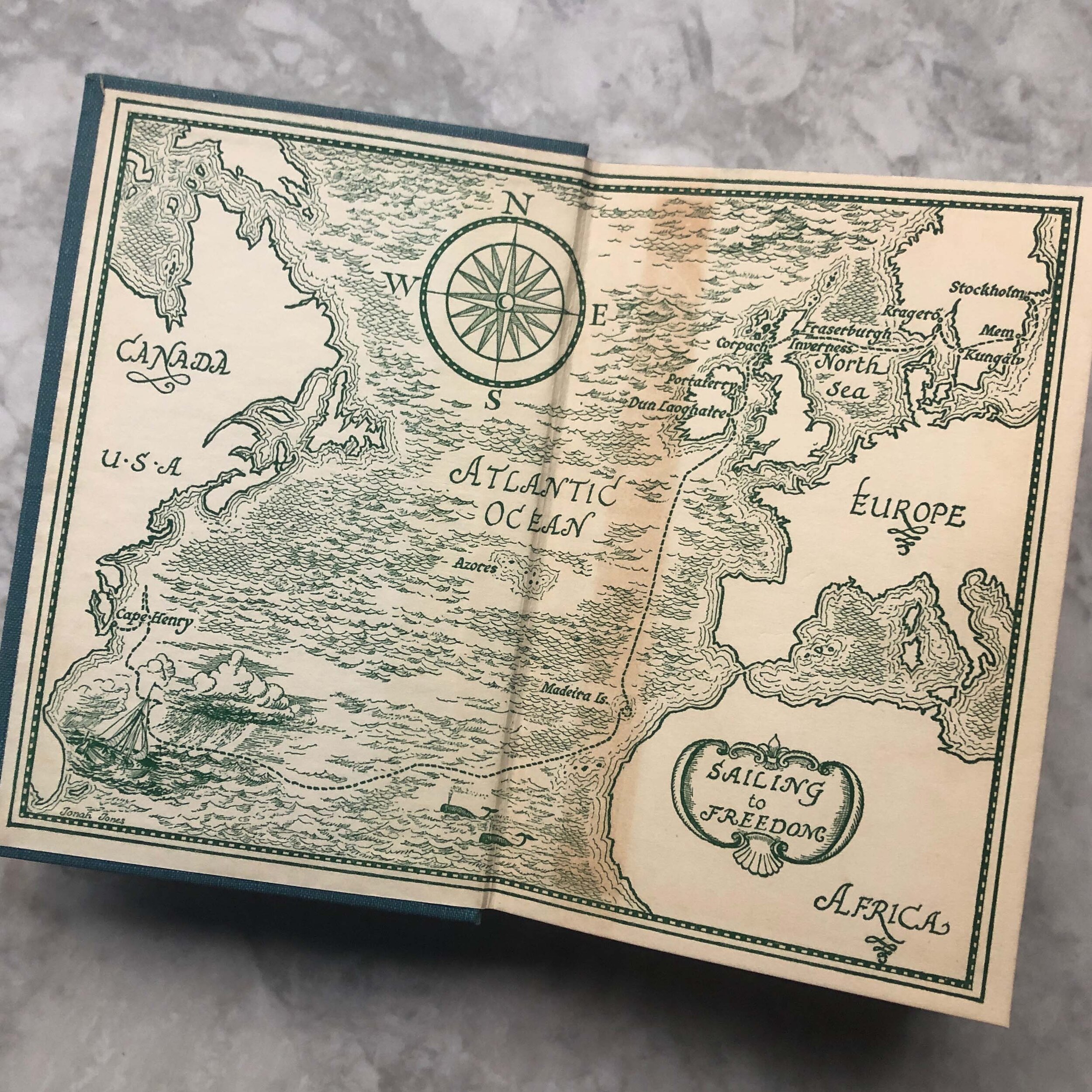

During the early 1940’s the Russians instigated mass deportations of ethnic Estonians to Siberia and the majority of those sent there never survived to get back to their own country. To escape these deportations many Estonians sailed across the Baltic to Sweden where they were largely held in camps amongst these escapees were the heroes of this book. They were faced with yet another problem at the end of the war as Sweden was set to send the Estonians back to their own country and Soviet control. In March 1945 Voldemar Veedam was sitting with his friend Harry Paalberg when the first of the letters from the Swedish foreign ministry were received by the refugees informing them that they were to be returned and the Soviets has assured the Swedish government that they would be safe. Needless to say, the refugees in Sweden didn’t believe the Soviet assurances and it turned out to be a correct supposition as tens of thousands more Estonians were sent to their doom in Siberia during the 1950’s.

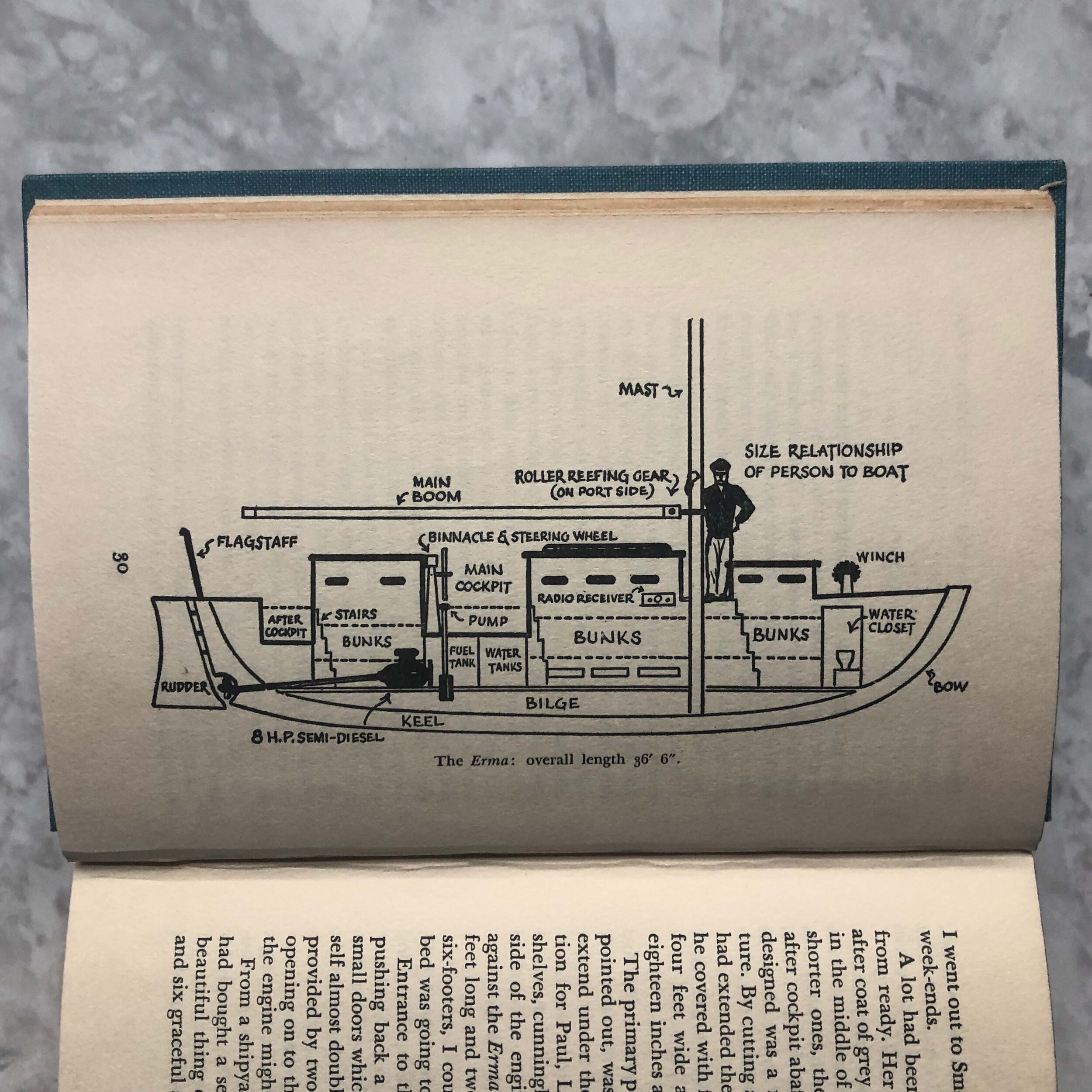

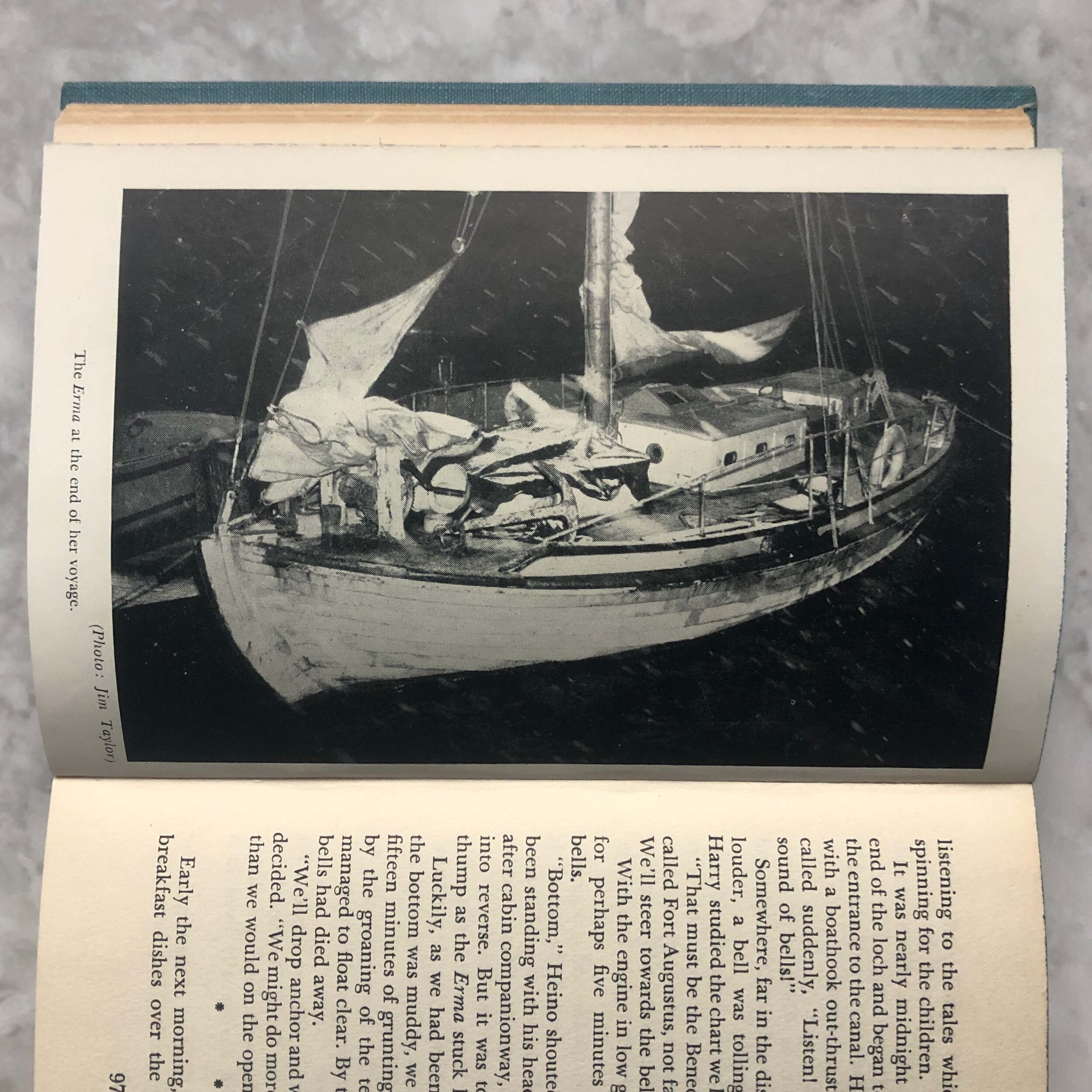

And so, the plan was hatched between Voldemar and Harry to escape, this time from Sweden and try to get to the USA. They would need a boat and a few more people to man it and also help raise the money needed for the trip; this was going to be difficult enough never mind the gruelling ocean voyage. Money was tight and they couldn’t get more from family abroad as Swedish law severely limited the amount that could be sent to the refugees. In the end they managed to purchase a 36½ foot long (11.1m) by 13 foot wide (4m) sloop called ERMA and an erratic diesel engine, but only by taking so many people into the escape attempt that the crew numbered twelve adults and four children. Working out how to get all those people on board with sufficient provisions and still be able to sail was a logistical nightmare. So much so that one of the recurring themes is the amazement of bystanders whenever they did manage to make it to a port as to how so many people were aboard. When they bought her Erma was over fifty years old and had been out of the water for years so leaked badly when she was refloated.

“Sailing to Freedom” was translated into many languages

There was a massive amount of work needed to make ERWA seaworthy and this took far longer than any of them hoped even with four men working up to sixteen hours a day rebuilding the boat to be able to get everyone on board. So much so that instead of the hoped for summer departure it drifted into the autumn and meant that they ended up crossing the Atlantic during November and December. This undoubtedly increased the amount of bad weather they hit during the crossing and caused a lot of the delays which hit their rations hard. It really is a magnificent tale of daring-do and remarkable seamanship that they managed to get all the way making repairs to their tiny vessel whilst on the way.

As you can see from the pictures the dustjacket on my copy is disintegrating after having lent it t so many friends. It’s a story that should be told in 2021, when tolerance and open-minded discussion, is so often replaced by fearmongering and fundamentalism.

Book Six

“The Happy Isles of Oceania- Paddling the Pacific by Paul Theroux

I don’t think this book is a great book….but I like it a lot for a couple of reasons…the first is that a lot of the journey takes place in a Klepper Kayak. This Inuit style kayak, is made of a folding wood frame and a pliable skin, folds into one, two or three carry bags for easy transportation, and has been developed by German craftsmen and engineers and perfected over 100 years into a state of the art, seaworthy kayak, with full upwind sailing capability.

I’ve always wanted one! The second is that Theroux is brutally honest about himself and his surroundings. I’ve read a lot of his books and I usually come away from them with a reinforced belief that he is not a nice man. It’s rare to find a travel book where no experiences are sugar coated…

This overly harsh review by Eric Hansen from 1992 gives you the idea!

When a marriage falls apart, a man will often turn to drink, sex, therapy or his work in order to blunt the pain of separation and his sense of failure and guilt. When Paul Theroux and his wife separated, he decided to paddle around the South Sea islands in a folding kayak.

Mr. Theroux's solution to the wrecked marriage, he tells us in "The Happy Isles of Oceania," his account of the journey, "was to keep paddling." This seemed like an excellent plan: To embark on a voyage of self-discovery. To get lost. It didn't matter where, but the South Pacific seemed like a good place. The crucial thing about this sort of journey is to keep going until you drop. Destination is unimportant, because, as the Indian sage M. N. Chatterjee often said: "If you don't know where you are going, any road will get you there."

It takes a while for Mr. Theroux to get his kayak in the water. First, there is a book-promotion tour of New Zealand and Australia, then a shakedown cruise on the northeast coast of Queensland, where he seems oblivious to the fact that a Government ban on killing saltwater crocodiles has produced a population of man-eating monsters. In recent years, a 22-foot crocodile was captured on the Queensland coast near Townsville; Mr. Theroux's fabric-covered kayak measures less than 16 feet.

Not wanting to attempt a crossing of the Torres Strait, which separates Australia from Papua New Guinea, Mr. Theroux flies to Port Moresby, then on to the Trobriand Islands, where he quotes from the personal diaries of Bronislaw Malinowski and captures the founder of social anthropology reflecting on the fruits of his field work: "The natives still irritate me," writes Malinowski, "particularly Ginger, whom I would willingly beat to death."

Most of Mr. Theroux's journey is by airplane, freighter and rental car, although there are scenic paddling trips along lush tropical coastlines. His mesmerizing account of a week spent camping on the uninhabited desert islands of Vavau, in Tonga's northern archipelago, prompted me to get out my atlas and make a few calls about air fares and the price of a secondhand sea kayak.

The subtitle of Mr. Theroux's book, "Paddling the Pacific," suggests an ocean passage following the ancient canoe routes that once linked the fabled South Sea islands, a voyage in which the rigors of crossing the sea would be interspersed with languid days spent in the shade of palm trees rustling in the trade winds. But visions of bare-breasted dusky maidens and a lone kayaker sliding down the face of deep blue ocean swells soon fade as it becomes clear that the primary purpose of the kayak is to transport its owner to remote island villages so he can make snide comments about the locals.

In "The Happy Isles of Oceania," Mr. Theroux's preoccupation with mocking strangers and passing hasty judgment severely limits his ability to transport the reader or capture the essence of the people he encounters along the way. The man seems to have an uncommon talent for meeting unpleasant people in beautiful places.

When the trip starts to go bad, Mr. Theroux has no illusions about the source of the problem: "It is quite easy in travel to project your own mood onto the place you are in; you become isolated and fearful and then find a place malevolent -- and it might be Happy Valley."

In any case, the cynicism is dealt out evenly. Of the French in Polynesia, he writes: "There is no cannibalism in the Marquesas any more -- none of the traditional kind. But there was the brutality of French colonialism." (In addition to the usual blights, this also encompasses French nuclear testing on Mururoa Atoll and the sale of fishing rights to the Japanese.) And Mr. Theroux has this to say about the spiritual guidance of the missionaries: "Mormonism was like junk food: It was American to the core and it looked all right, but it wasn't until after you had swallowed some that you felt strange."

Mr. Theroux's travels take him through the islands of Melanesia and Polynesia, and en route we learn about eating dogs and cats, the "mweki-mweki" dance and the erotic Yam Festival of the Trobriand Islands. We are introduced to the Jon Frum cargo cult from Vanuatu, the shark callers of the Fiji Islands and the star charts of the ancient Polynesian navigators, plus an assortment of migration theories that are high lighted by Mr. Theroux's ironic suggestion that Thor Heyerdahl, the author of "Kon-Tiki" and "Easter Island: The Mystery Solved," in clinging to his discredited east-to-west migration theory, is no more scientific than the Mormons, who believe that one of the Lost Tribes of Israel sailed from South America to populate Polynesia.

Most travelers want to be taken seriously by the local people. It helps justify the journey. Mr. Theroux is no exception, but this sort of endorsement can be a difficult thing to come by, especially if you are a white stranger who shows up on the beach (which traditionally doubles as the local toilet) in a folding kayak, wearing a baseball cap and sunglasses, listening to Chuck Berry on the Walkman. Can the seasoned traveler really expect subsistence fishermen and their families to comprehend the idea of paddling a kayak as a way of coming to terms with a failed marriage?

AFTER 51 islands and nearly 500 pages, the author finally comes to ground in the Hawaiian Islands, where he tours the strip joints of Honolulu, drinks beer, looks at naked women and contemplates the vulva worship of Hinduism. Vile natives have long since stolen his $300 cowboy belt, but, by the grace of God, he still has sufficient funds to stay in a $2,500-a-night bungalow at the Mauna Lani Resort.

The grand tour of Oceania ends with Mr. Theroux describing travel writing as "a horrid preoccupation that I practiced only with my left hand." He then proceeds to make the claim that "I was not sure what I did for a living or who I was, but I was absolutely sure I was not a travel writer."

"The Happy Isles of Oceania," with its studiously cynical vision of paradise lost, should make excellent reading for those people who don't want to travel or don't like to travel. It will reassure them that it is best to stay at home and not think too much about how else they might lead their lives. Paul Theroux has long since mastered the craft of writing, but, after finishing this book, I found myself wondering if he will ever master the fine art of travel."

Book Five

“Sailing the Pacific” by Miles Horden

“Many of the things that I remember about the passage through the tropics happened at night. Daylight can be a corrosive force on the tropical seas. It is an anomaly of the marine landscape: by day, there is often nothing to see. The sky is hard and burnt, the water a bulge of silver reflections.”

This is another very individual account that covers in detail a quite remarkable voyage but like all great sailing books, isn’t really about sailing at all. (and I can’t really go past a story that stars a folk boat…. We have an article coming up in the next few weeks about a very special craft of this design)

Back in the early 1990s, a young man called Miles Hordern sailed his 28ft Kim Holman-designed Twister single-handed from the UK to New Zealand. He lived aboard in Auckland for the first winter before moving ashore and becoming progressively divorced from the sea.

Kim Holman, The Twister’s Designer

After five years, however, the call of the Pacific could no longer be denied and he set himself a voyage around the current system of the world’s greatest ocean. Following the streams, he sailed the Twister across the Southern Ocean to Chile, cruised the archipelagos, then headed for Easter Island before following the classic South Seas route back to New Zealand.

Hordern is remarkably unsentimental about his 28-footer, rather small for so formidable an ocean, and he is not spooked by the legendary weather regularly dished out in such latitudes. Not that Hordern is smug or stupid; he simply finds himself an inextricable thread woven into the history of sailing the South Pacific: “bound up with Greek cosmologers, medieval mapmakers, poets, and whalers.” His equipment is simple and efficient, he likes what he is doing, he trusts the auguries. He won't ignore a storm warning, but what really raises the hair on his neck is reading that a set of reefs or shoals are doubtfully positioned on his chart, perhaps phantoms altogether; though Davis Land, Sophie Christiansen Shoal, and Emily Rock have been spotted numerous times, they’ve failed to be spotted an equal number. While he appreciates GPS as part of the routine when he gets his noon fix, he’s more impressed by how he has become a sea creature in his own right. “You have an agility, a set of physical skills, that aren't needed on land,” he comments.

Here is a sample of his mesmerising writing.

On deck the trade was fresh, between 20 and 25 knots, warm and woolly; in these latitudes the wind is a light angora that surrounds your whole body, tugging in the direction of the flow. I ran between 140 and 150 miles a day, and was sure it could get no better than this. At 27°S I altered course and sailed due west for Easter Island, some thousand miles beyond the horizon.

Over those days the sea took on a quality I hadn’t expected, measuring out the miles as if progress was a certainty. The swells were a metre high, sometimes a metre-and-a-half, perfectly suited to a boat of this length. As each one passed around the keel I felt my home perform a cycle of predictable motion, lifting at the stern, dipping to leeward, always stiff and reasoned.

After breakfast each morning I faced the prospect of a whole day of easy progress. In the cabin I had time on my hands, surrounded by an ocean world of wind and seas that appeared almost mechanical.

I cut my hair and trimmed my beard. I sat with charts and books of the islands ahead and dreamed that this might be my best passage. It was light and warm: this alone was sufficient to guarantee contentment. I drank lime juice from a glass placed on the gimballed cooker.

I found pleasure in simply looking at that glass. It was a heavy, round tumbler, a little taller than the width of my hand. I had never used a glass in the Southern Ocean for fear of breakages; instead, I drank everything from one stainless steel tankard. But in the trades glassware could again be part of the fabric of my life.

I looked proudly at the glass sometimes, as sunlight flashed through the airy cabin. I saw it as a trophy of the peaceful times I had won for myself. As the tradewinds settled into place over the ocean, I all too quickly became accustomed to this genteel world of sipped drinks and mahi mahi steaks poached in Chilean chardonnay. It was easy to forget how quickly it could all fall apart.

Many of the things that I remember about the passage through the tropics happened at night. Daylight can be a corrosive force on the tropical seas. It is an anomaly of the marine landscape: by day, there is often nothing to see. The sky is hard and burnt, the water a bulge of silver reflections.

When the wind is light, the heat is desperate. During the day I often hide in the shade, seldom venturing out for long. There are events hidden among the shadows and languor, of course, but they are indistinct.

Critically, in my memory, all lack a clear starting point at which any one event can be said to begin. And because most things that happen at sea are so routine and inconsequential, without a starting-point, they disappear.

Through it all, Hordern is a master of deadpan: “I made landfall on the coast of Chilean Patagonia in mid December, after a six-week passage.” Falling overboard during a squall is a worthy little story, but more fascinating to Hordern is an event “easy to describe . . . not easy to explain”; when he got to Easter Island after some serious sailing, he scooted on past. Similarly, within hailing distance of New Zealand on his return, Hordern turned his boat around and sailed aimlessly for three days, finally landing in Fiji. He confides to a friend that he thinks it was a nervous breakdown. Like I said…. It’s not just about the sailing.

Book FOUR

“The Worst Journey in the World” by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

“Because of the birds' mating habits, the only time to acquire their eggs was during the unending dark of a polar winter. An extended trek at that season had never been attempted. Cherry dryly remarks 'I advise explorers to be content with imagining it in the future.”

A few years ago, National Geographic magazine compiled a list of the 100 greatest works of non-fiction adventure. Ranked No. 1 'The Worst Journey in the World,” Apsley Cherry-Garrard's memoir of the 1910-1913 Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica under the leadership of Robert Falcon Scott.

In 1909, Terra Nova was bought by Captain R.F. Scott RN for the sum of £12,500, as expedition ship for the British Antarctic Expedition 1910.

Reinforced from bow to stern with seven feet of oak to protect against the Antarctic ice pack, she sailed from Cardiff Docks on 15 June 1910. He described her as "a wonderfully fine ice ship.... As she bumped the floes with mighty shocks, crushing and grinding a way through some, twisting and turning to avoid others, she seemed like a living thing fighting a great fight"

A full decade after what was left of the expedition had returned, Cherry brought out 'The Worst Journey in the World,” weaving in numerous extracts from his friends' letters and diaries.

Surprisingly, though, his book's title doesn't actually refer to Scott's ill-fated return from the pole but to an earlier expedition, one with a happier ending.

We all know about Scott’s heroic or (as it is increasingly regarded nowadays) misguided journey

Eager to plant the English flag at the South Pole, 8,000 men applied to join Scott's expedition, with just 33 chosen for the actual land contingent. Partly through friendship with chief scientist Edward Wilson, the 24-year-old Cherry-Garrard was taken on as 'an adaptable helper,” though he had no experience of polar exploration and was extremely nearsighted. Nonetheless, 'Cherry,” as he was called, would end up sledging more than anyone else, some 3,000 miles.

At times he and his comrades endured what few of us can imagine: temperatures close to 70 degrees below zero and hurricane-force winds; sleeping bags and clothes frozen into solid blocks; a diet consisting mainly of biscuits, seal meat and penguin; constant fatigue.

Late in 1911 Scott and four companions made a final push for the pole, only to discover that the Norwegian Roald Amundsen had reached it a month before. On the journey back, the weather grew extreme and nothing went right. Edgar Evans died near the Beardmore Glacier. Soon afterward, Capt. Lawrence Oates found himself limping painfully because of an old Boer War injury, exacerbated by scurvy. Realizing that his rapidly deteriorating condition was endangering the lives of his comrades, Oates simply left the tent one morning and hobbled away into a blizzard. His last words still bring me - and many others - to tears: 'I am just going outside and may be some time.”

Alas, his sacrifice came too late. Scott and Cherry's two closest friends, Wilson and H.R. Bowers, pushed on a bit farther until, exhausted and weak from hunger, they pitched their tent for the last time just 11 miles from the depot where Cherry waited with the supplies that would have saved them. He couldn't have known that Scott and the others were so close, but in years to come he would suffer unassuageable remorse for not having left his post and gone out searching for them.

But this book is about a different journey

On his first visit to Antarctica in 1901-1904, Wilson had discovered that Cape Crozier provided a rookery for emperor penguins. Because of the birds' mating habits, the only time to acquire their eggs - which Wilson believed might supply important evolutionary information - was during the unending dark of a polar winter. An extended trek at that season had never been attempted. Cherry dryly remarks 'I advise explorers to be content with imagining it in the future.”

On June 27, 1911, Wilson, Bowers and Cherry left their base camp, dragging two nine-foot long sledges loaded with 757 pounds of supplies and equipment. They would be gone for five weeks. Much of the time they could barely see the ground at their feet. One day they only managed to travel one and a half miles. By the time the trio reached the penguin rookery, Cherry writes that he would have given five years of his life for just one night in a warm bed.

The real ordeal, however, had only begun. The men constructed a hut next to their tent, just before a three-day blizzard struck. Its ferocious winds first blew away the tent and then shredded the hut's canvas roof. Exposed to the elements, Cherry and his companions burrowed into their sleeping bags, as the snow piled up on top of them. All three knew that without a tent it would be almost impossible to survive. I won't say more but, against all odds, they do survive and even bring back three emperor eggs. As they finally reached safety, Wilson thanked Bowers and Cherry for what they had all suffered through, adding 'I couldn't have found two better companions - and what is more I never shall.”

Cherry merely says, 'I am proud of that.” A few months later, Scott enlisted Wilson and Bowers for the final assault on the pole. Till the last moment, it had been a toss-up whether Oates or Cherry would be the fifth member of the team.

Above all, it is a celebration of character, a memorial to the quietly competent, utterly admirable men for whom 'the expedition came first, and the individual nowhere.” They were, as Cherry shows us again and again, the kind of comrades with whom you would happily trust your life.

After returning to England, Apsley Cherry-Garrard served in World War I, married and lived to be 73, dying in 1959. Still, little in those subsequent years seemed to matter much to him compared with the joys and sorrows, the sheer intensity, of the experiences chronicled in 'The Worst Journey in the World.” He never wrote another book.

Book Three

“The Unlikely Voyage Of Jack De Crow” by A.J. Mackinnon

“This seemingly guileless figure, wearing a pith helmet and sailing a yellow dinghy with a red sail and an ensign emblazoned with the figure of a crow, finds hospitality almost everywhere he goes.”

Ok, you might have spotted the problem with the first two suggestions for this week of SWS Adventures? Neither boat was timber, and neither trip had an Antipodean connection. Well, today we put that right with a Mirror Dinghy voyage across Europe by a school teacher from Victoria, Australia. It might not have the gravitas of Moitessier or Raban’s accounts (see below) but what it lacks in heft, it makes up for with humour.

Here’s a review from 2008 by SMH writer David Messer

The phenomenon of authors travelling to exotic places, doing "wild and crazy" things and then writing a book about their experience has become commonplace.

Some of these have been extremely successful, some are very good books but increasingly many seem contrived, self-obsessed and even formulaic.

That Australian author A.J. "Sandy" Mackinnon has written one of the finest examples of this kind of book is thanks not so much to his taste for adventure, unbounded and admirable though it is, but to his intellect, wit and talent as a writer.

Mackinnon's story starts mildly enough. In 1998, aged 35, he had been teaching for six years at a "Hogwarts-like" private college in Shropshire. Here he distinguished himself in his first year as the owner of Jack, a mischievous crow.

The college had a sailing school and included among its vessels an ancient Mirror-class dinghy. Inspired by Narnia, Doctor Dolittle and similar ripping yarns, Mackinnon had the idea of leaving the college by sailing away in this dinghy, just to "see where I got to - Gloucester near the mouth of the Severn, I thought".

Buoyed by optimism but unprepared and ill-equipped, Mackinnon set off in his craft, dubbed "Jack de Crow", bumbling his way along rivers, creeks, canals, and through locks. Passing his initial destination, he decided to attempt a crossing of the English Channel and continue through the Continent. After more than a year, he completed his journey, having sailed all the way across Europe from a small river in Shropshire to Romania and the Black Sea.

Mackinnon's charms, both as a person and a writer, probably owe something to a childhood spent in Australia and England. He has the relaxed openness of an Australian combined with two things the English do best - humour and eccentricity. It also helps that he is very accomplished at some things and hopelessly ignorant of others, some of the latter being vital to his enterprise.

Mackinnon, for example, is obviously well educated and his writing (and indeed the voyage itself) is enlivened by literary quotations and references. He is also a reasonably experienced sailor. On the other hand, his map reading (and his choice of maps) leaves a lot to be desired. At the beginning of his adventure, he did not know how to row, problematic considering he couldn't use the boat's sail for the first few days.

Despite and because of these contradictions, Mackinnon managed somehow to keep going, along the way overcoming an almost complete lack of planning, streams that turned into unpassable bogs, torrential currents, unpredictable tides, broken keels, hulls, rowlocks and masts, lack of food and money - even pirates.

This seemingly guileless figure, wearing a pith helmet and sailing a yellow dinghy with a red sail and an ensign emblazoned with the figure of a crow, finds hospitality almost everywhere he goes. Almost always he is saved by his likeable personality and the kindness of strangers. At one stage, he washes up on a bleak strip of coast miles from the nearest town. The owner of the nearest house insists on his staying the weekend while her son-in-law, who just happens to be a boatbuilder, refurbishes the dinghy.

Mackinnon, Jack de Crow and the places he visits, are made more vivid by the author's illustrations, maps and diagrams. Apart from the fact that he is a very funny writer and his true story is intrinsically interesting, what sets him apart from many travel writers is his tone.

P.J. O'Rourke, for example, is very funny but in the end distastefully mean-spirited, a self-consciously ugly American. Even the less knowingly caustic Bill Bryson founds his travel writing on humour at the expense of others. Mackinnon, on the other hand, while describing a lot of funny people and places, always laughs most at himself. It's this fundamental empathy for and curiosity about unfamiliar people and places, and a lack of self-importance that makes him a great travel writer and more importantly a great traveller.

book Two

“The Long Way” By Bernard Moitessier

Charles Doane wrote of Moitessier….. “It is interesting that our three major monotheistic religions–Judaism, Christianity, and Islam–are all the fruit of mystic transmissions received by prophets who isolated themselves in the desert. And in Buddhism, of course, though it is not really theistic, we have a belief system based on the enlightenment of a man who isolated himself beneath a tree. But curiously, though humans have long wandered across the watery part of our world, an inherently isolating experience, from the very beginning of our existence, we have in our history no real prophet of the sea.

I think most would agree now that the man who most closely fits the description is Bernard Moitessier, the iconoclastic French singlehander who became notorious in 1969 after he abandoned the Golden Globe, the first non-stop solo round-the-world race, so as to “save his soul.”

“Most sailors probably would also agree that the book Moitessier wrote about his experience, The Long Way (La longue route in the original French, 1971), though it obviously has never spawned any sort of religion, is the closest thing we have to a spiritual text.”

Toby Litts 2019 review of the book, places it nicely in a contemporary frame work.

“First published in 1973, if The Long Way is dated, it’s in a melancholy way. The book ends – after Moitessier’s circumnavigation and more – with the wise sailor encountering environmental destruction on Tahiti. He becomes engaged, politicized, after months of selfish (in a good way) voyaging. Just him, the Joshua his boat, the porpoises, the sea robins, the sky, sea, sun and moon. But you can’t help but feel, if we could dial the planet back to the state it was in in 1973, we would be a long way towards some kind of eco-sanity. Not perfect, but nowhere near the point we are now.

Some moments in The Long Way jar painfully. Moitessier’s departure from his wife and children. His avoidance of them throughout his time away. Also, the amount of stuff he chucks over the side of the boat – to save weight. He does not have a contemporary sensibility. He gleefully smokes his way around the world. He is not a saint. But he’s on a genuine quest for something. Hence his famous message to the Sunday Times:

‘Dear Robert: The Horn was rounded February 5, and today is March 18. I am continuing non-stop towards the Pacific Islands because I am happy at sea, and perhaps also to save my soul.’ (This is a forerunner of Bruce Chatwin’s invented telegram to his editor ‘Have gone to Patagonia’.) The Long Way is one of the great books about the satisfactions of isolated dedication to a task. It is full of contradictions. Moitessier is both at rest but also involved in a gung-ho race – against other solo sailors but also against the seasons. Moitessier is a yoga-performing hippie sympathiser, but he’s also a very old kind of macho.

I re-read this, listening to Dave Crosby’s ‘The Lee Shore’ in a fairly obsessive way. If you’re a city-dweller who wants to run away to sea, that combination is the best I can offer.

And if you’re engaged on any long project (for example, writing a novel or recovering from an illness), Moitessier is a great companion to have in your solitude.”

‘One thing at a time, as in the days when I was building Joshua. If I had wanted to build all the boat at once, the enormity of the task would have crushed me. I had to put all I had into the hull alone, without thinking about the rest. It would follow… with the help of the Gods.

‘Sailing non-stop around the world. I do not think anyone has the means of pulling it off – at the start.’

book one

“Passage to Juneau” by Jonathan Raban

In 1992 while living aboard a little plastic boat on the South Coast of England, I started reading COASTING by Jonathan Raban. It’s an account of a timid and fraught journey around the coast of Britain, at the hight of the Thatcher years. It changed the way I thought about travel, boats and politics so when PASSAGE TO JUNEAU came out in 1999 a was very ready to learn more about boats and life…

This brilliant review by Sarah Crown was first published in The Guardian 2015,

In the late 1990s, Jonathan Raban waved a “heartsore” goodbye to his wife and daughter on a Seattle quay and put to sea for Juneau, Alaska. The purpose of the voyage was, expressly, “work”. Raban’s already substantial reputation rested on a series of books that found shelf-room in bookshops’ Travel sections, and were united by their fascination with water: he steered a skiff through the rich soup of the Mississippi in Old Glory, sailed solo around Britain in Coasting, crossed the Atlantic in a container ship in Hunting Mister Heartbreak, and in Bad Land, prayed for rain. The Inside Passage – a thousand-mile-long crosshatch of channels and islands – home to native Americans, colonised by Europeans, fished to exhaustion and nowadays serving as the sublime backdrop to a booming cruise-ship trade – was on his doorstep. Newly a father, and reluctant to stray too far from home, it made excellent professional sense to turn it into the subject of his next book.

Raban’s idea was to follow in the oar strokes of those who’d travelled the Passage before him, considering the different meanings and interpretations they’d projected on to its surface and in to its depths. He’d read up on the coastline’s history – the mythology of the Pacific northwest’s indigenous people and Captain George Vancouver’s irascible account of his 1792 expedition – and equipped himself with a library that included Shelley, Waugh, Edmund Burke and Claude Lévi-Strauss. He was, he believed, all set. “I had a boat, most of a spring and summer, a cargo of books and the kind of dream of self-enrichment that spurs everyone who sails north from Seattle,” he says, with casual, almost glib intention. “Forget the herring and the salmon: I meant to go fishing for reflections, and come back with a glittering haul. Other people’s reflections, as I thought then. I wasn’t prepared for the catch I eventually made.”

Neither was I. In fact the second half of that passage, with its gaudy metaphor, seemed to me, when I first read it, to draw unnecessary attention to something we all take for granted: that when it comes to literature, any physical expedition will reflect the interior one. I was fully expecting Passage to Juneau to contain a measure of self-discovery, but assumed Raban’s implication that he’d find himself fielding curveballs was a bit of forgivable dramatisation, and that any revelations would be of the mildest kind. As a fan of his, I really ought to have known better: his claim of unpreparedness is, it turns out, a simple statement of fact. Having taken the decision to cast off from family life, he comes to find himself at the mercy of a series of personal tides and cross-currents that prove, in the end, unnavigable.

Raban’s rendering of the journey itself is superb. “I am afraid of the sea,” he admits candidly at the beginning of the book. “I fear the brushfire crackle of the breaking wave as it topples into foam; the inward suck of the tidal whirlpool; the loom of a big ocean swell, sinister and dark, in windless calm; the rip, the eddy, the race.” Nevertheless, he’s drawn to it, and no one writes better than he does about water: his prose, always supple and beguiling, takes flight when he sets sail. In his hands, the Inside Passage comes vividly to life: dark green forests, rocky outcrops and worn-out logging and fishing communities above the waterline; abyssal depths below. He’s brilliant on the sea’s hallucinatory quality – the way it plays tricks with light and distance; its ability to shift in a second from benign to boat-wrecking – but his layovers in the two-bit towns that dot the rippling coastline, filled with descriptions of supermarket trips and frequently unsuccessful quests for a working telephone, are just as eloquent. His knack for bringing to life the men and women he encounters in the space of just a couple of sentences puts many a novelist to shame.

Had he left it at that, Passage to Juneau would have been recognised as an outstanding travelogue – but it’s what happens away from the sea that transforms it into a masterpiece. Midway through his voyage, Raban fields a phonecall from his father during the course of which he admits, apologetically, that he is dying. Raban finds a harbour for his boat and and travels halfway around the world to his parents’ retirement bungalow in a bland English village, where conifers and channels are replaced by “candy-striped garden chairs and crazy paving”, and meditations on the sublime by gruelling discussions of morphine and soiled sheets. After discharging his duties as a pallbearer, he returns to Canada and continues on his way, but wherever he looks, now, he sees his father; the rest of the voyage becomes a grappling with the idea of death – his father’s and, from there, the inevitability of his own. What’s more, he discovers, when he finally makes landfall, that his own nuclear family is not the safe haven he believed it to be. He ends the book on dry land but helplessly at sea: fatherless at 50, and no longer in possession of the self-made family that he’d counted on to ease his loss.

“Journeys,” says Raban, somewhere towards the end of Passage to Juneau, “hardly ever disclose their true meaning until after – and sometimes years after – they’re over.” This book was conceived of as a piece of work, but the professional project is, in the end, wholly subsumed by a floodtide of personal crises that leave the author gasping for air. Did he contemplate keeping them off stage and sticking to the route he’d blithely plotted, back in his Seattle study? Perhaps – but like any good captain, Raban elects in the end to go down with his ship. Passage to Juneau is not the book Raban set out to write. It’s richer, rawer and far, far more rewarding than that.

This Book review by Sarah Crown first appeared in The Guardian 2015.