An Ama to Windward

As you may know, the theme for the 2025 AWBF is “New Zealand & The Pacific”. So when we received this article from Graham Cox about a Pacific Proa it seems to be particularly apposite.

By Graham Cox

JZERRO in Breakwater Marina, Townsville, Australia, 2002.

One of the greatest pleasures of cruising under sail, for me, is the other voyagers you meet, and their boats. I consider it to be just as rewarding as making passages and exploring new landfalls. Back in the 1960 and 70s, when I became involved, almost every boat was unique, a reflection of the owner’s personality or circumstances, whether they were old boats repurposed for the task or new builds. While this is still true to some extent, it is becoming rarer.

One boat that really stood out as a unique expression of its creator’s imagination and vision was Russell Brown’s Pacific proa, Jzerro, which I crossed paths with in Townsville, FNQ, Australia, in 2002, as detailed in Volume Two of my sailing memoir, Last Days of the Slocum Era. I’d read about Russell and his proas occasionally in yachting journals, though they all said he liked to keep a low profile, and he has never sold plans for his designs or written about his passages.

JZERRO in Breakwater Marina, Townsville, Australia, 2002.

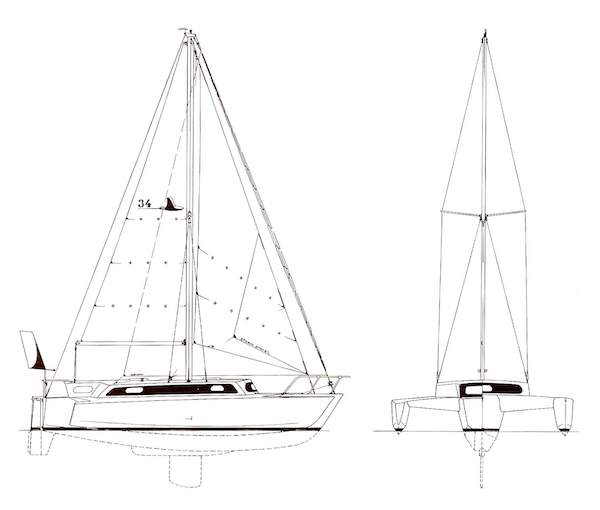

He is the son of trimaran pioneer, Jim Brown, whose most famous designs were the Searunner range; sensible, attractive, and seaworthy trimarans that came to the attention of mainstream yachting, and did much to advance the acceptance of multihulls. One of his designs was featured in the Time Life Library of Boating. His Searunner 34, the distillation of his work on that series, has been described as the safest ocean-cruising trimaran ever designed. It has enough reserve buoyancy built into its decks that, in the unlikely event of a capsize, the crew can comfortably live inside the boat until rescued.

Searunner 34

Jim, in his heyday, became more than just a yacht designer. Even though it was never his intention, he became something akin to a cultural icon, a symbol of the alternative way of doing things and living, which was so popular in the 1960-70s. His boat designs and writings appeared in places like The Whole Earth Catalogue. People, often counterculture types, began to seek him out, beating a path to his door to hear the words of wisdom from the master himself. One stranger, I heard, even turned up at the family homestead on Christmas Day. Jim’s book, The Case for the Cruising Trimaran, became a best-seller and remains in print. His design catalogues were treasured. I had a set myself.

I am not sure if observing all this influenced Russell, but he has steadfastly avoided the cult of celebrity throughout a long and creative life spent designing and building boats. He is now considered a master craftsman in timber-epoxy-composite construction, working out of a workshop in Port Townsend, alongside his wife, Ashlyn, called Port Townsend Watercraft. They have also written a number of technical books to help others develop their boatbuilding skills. Their website, (see above) detailing their publications and the work of friends, also has a link to their blog. For people outside of the USA, the print versions of their books are available on Amazon and elsewhere.

When Russell was in early adolescence, he and his brother, Steve, set sail from California with their parents on the trimaran, SCRIMSHAW, a Searunner 31, bound for Mexico, South America and the Caribbean, ending up on Chesapeake Bay after three years. Along the way, a family friend, the trimaran designer, Dick Newick, sent them a copy of the book, Project Cheers, an account of Tom Follet’s triumph in the 1968 OSTAR (singlehanded transatlantic race), with the Atlantic proa, CHEERS, which lit a fire in 13-year-old Russell’s mind.

SCRIMSHAW. Photo: courtesy Russell Brown.

He was soon out sailing on an improvised proa, created with the imagination and energy that came to characterise his later creations. Rather than just mimic CHEERS, despite being enthralled with the boat, Russell chose to configure his makeshift craft as a Pacific proa, like the traditional Polynesian boats, which always keep the ama to windward.

The Pacific proa configuration has many advantages, including considerably less load on the beams, and thus the rig. Having the ama to windward, although seemingly counterintuitive, is actually safer, as its weight, combined with reserve buoyancy in the main hull’s leeward pod, makes the boat much more resistant to capsize. The ama could also be filled with water via a hand pump, and emptied the same way, though Russell rarely utilised that option.

Returning to the conformity of school in the USA wasn’t easy for Russell. At the age of 17, he built a 30ft sheet-plywood Pacific proa, JZERO , named after a Cat Stevens song, for US$400, and took off back to the tropics. In 2002, he told me that in some ways he considered this to be his best design, so simple and pure in concept.

JZERO sailing off Martinique, in the Caribbean. Photo: courtesy Russell Brown.

JZERO came apart in the ugly seas of the Gulf Stream off Florida, but he clung to the wreckage, refusing rescue until someone came along who was willing to take the boat as well as himself. He rebuilt it on a beach in Florida and, with a new friend, Mark Balough, sailed for the Caribbean. Mark remembers the trip as terrifying, but Russell was in his element. Like a Polynesian navigator, he had learned to live with the sea, not fight or fear it.

JZERO on the beach in St Croix, Virgin Islands. Russell is touching up the paintwork while Cynthia Hatfield, wife of multihull designer, Roger Hatfield, works at the bow. Photo: Roger Hatfield.

The experience could also be seen as a practical course in multihull design and construction, as JZERO went on to have a successful career, cruising and racing in the Caribbean, after which Russell built the cold-moulded timber proa, KAURI, in which he cruised for many years between the Caribbean and the east coast of the USA, carrying his tools and working in boatyards along the way. He also built another proa, CIMBA, for a close friend, before moving to Port Townsend and building the 36’ JZERRO, also cold-moulded.

In JZERRO , he sailed across the Pacific Ocean to Australia and New Zealand, before taking the boat apart and shipping it back to Port Townsend in a container. The well-known American sailor and writer, Steve Callahan, sailed with him as far as Tahiti, from where he carried on singlehanded. In the region of the Cook Islands, JZERRO weathered a 60-knot storm, lying safely hove-to, with the pod, which sits to leeward, occasionally smacking the water and bringing the boat back onto its feet.

JZERRO sailing in the lagoon at Bora Bora, Society Islands, photographer unknown.

These leeward pods have been a feature of all of Russell’s designs, influenced by the pod on CHEERS, that was added after it capsized during a trial sail before the OSTAR. The OSTAR committee initially refused CHEERS entry after this incident, but reversed their decision after Tom Follet and Dick Newick demonstrated the efficacy of the pod. It may well be that the pod, combined with the weight of the ama to windward, makes a Pacific proa the most capsize-resistant of all multihull configurations.

In a sweet incident of serendipity, Russell met David Lewis, author of We the Navigators, the revered text about traditional Polynesian navigators and their methodology, at Great Keppel Island, on the central coast of Queensland. Having sailed on a number of indigenous Polynesian proas, David, who, at 85, was in the last months of his life, was delighted with the opportunity to inspect JZERRO .

David Lewis on the beach at Great Keppel Island. Photo Russell Brown.

Even though David had written to me about the encounter, I was still astonished to stick my head out of ARION’s hatch one glorious tropical winter morning in Townsville, and find JZERRO moored opposite. Russell was a bit reserved initially, but once he realised I was enthralled with the boat, and understood the history and characteristics of proas, we became good friends. He gave me a picture of David he’d taken on the beach at Great Keppel Island that I still cherish.

He drew a sketch of a 30ft proa for me, on a page torn out of his notebook, that looks remarkably like the proa MADNESS that Chesapeake Light Craft developed a few years later in consultation with Russell. I often look at Madness and dream about zipping around the islands of Queensland on it. I’d have to have a storage unit ashore for all my books and large tools, however!

Proa MADNESS. Photo: Chesapeake Light Craft.

JZERRO has gone on to have an even more remarkable history than it had with Russell. After cruising JZERRO in the Pacific Northwest for many years, Russell sold the proa to Ryan Finn, who used it to challenge the non-stop New York to San Francisco sailing record, via Cape Horn. Despite having to stop for repairs, Ryan completed the passage in 93 days, with a sailing time of only 73 days, which is the fastest time ever recorded for this famed and feared passage. Undoubtedly, Ryan Finn is an exceptional sailor, but it also says something about the capabilities of a well-designed and built Pacific proa.