Banka Musing

Words and Photographs by Mark Chew

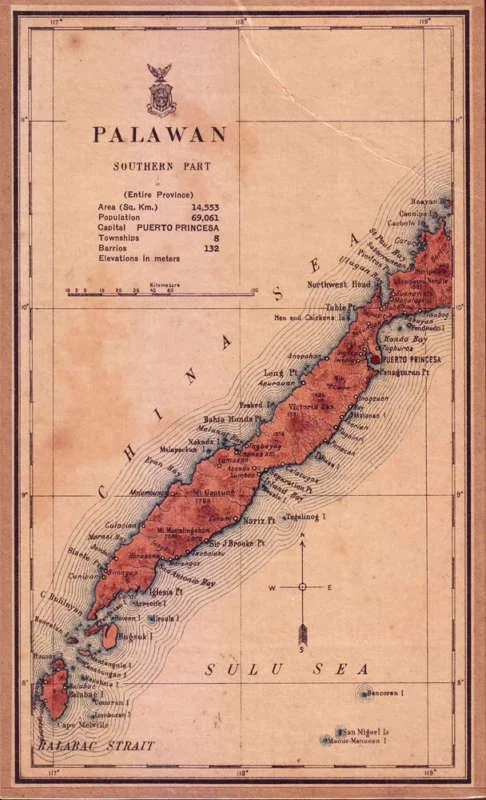

At ten degrees north of the equator, the sun sets at close to six o’clock every night. In the remains of the fast-vanishing light, a haze of woodsmoke drifts down the beach as a fisherman paddles a tiny outrigger back through the small surf after loading a larger Banka for a night of fishing off palawan’s west coast.

The paddler a small young man, with well-defined muscles, nimbly guides the fragile little craft back from the mother boat, having loaded up with ice, fuel, and charcoal, the necessities for a successful outing. His “oneness” with the boat hints at generations of seafaring ancestors.

But let’s not over romanticise the scene. The ice is carried in environmentally horrible and fragile polystyrene containers and amongst the woodsmoke there is a waft of burning plastic. The fisherman’s t’shirts are emblazoned with the logos of America’s most grasping corporations and be careful where you stand as the beach is littered with broken bottles that recently held cheap spirits

Given that the Philippines consists of over 7500 islands it’s hardly surprising that there is a generic term to cover most local craft, and that word is Banka.

It originally referred to small double-outrigger dugout canoes used in rivers and shallow coastal waters, but since the 18th century, it has expanded to include larger lashed-lug ships, with outriggers. Although the term used is the same throughout the Philippines, "bangka" can refer to a very diverse range of boats specific to different regions.

The expression lashed-lug refers to the construction method of these craft. The keel and the base of the hull is a simple dugout canoe. Planks are then added gradually to the keel, either by sewing fibre ropes through drilled holes or through the use of internal dowels ("treenails") on the plank edges. Unlike carvel construction and in common with many early boat building methods, the shell of the boat is created first, prior to being fastened to the ribs. The seams between planks are also sealed with absorbent tapa bark and fibre that expands when wet or caulked with resin-based preparations.

The most distinctive aspect of lashed-lug boats are the lugs (or cleats). These are a series of carved protrusions with holes bored into them on the inside surfaces of the planks which are then lashed tightly together with the lugs on the adjacent planks and to ribs using plaited fibre.

The seams of the planks were commonly caulked with resin-based pastes made from various plants as well as tapa bark and fibres which would expand when wet, further tightening joints and making the hull watertight. The ends of the boat are capped with single pieces of carved Y-shaped wooden blocks or posts which are attached to the planks in the same way.

In two weeks of travelling and observing hundred of these boats, I didn’t see a single sail. I’m told in the 1960’s over half the fleets were still powered by wind with a mastless triangular rig carrying a crabclaw sail which had two booms that could be tilted to the wind. The sails were made from mats woven from pandan leaves. The triangular crab claw sails also later developed into square or rectangular tanja sails, which like crab claw sails, could be tilted against the wind.

Nowadays the chosen method of propulsion is a cheap Chinese diesel 18HP air cooled motor, called a Kingston which retails online for USD$265. Unsurprisingly, at this price many of the boats carry two, with the shafts arranged one above the other on the central line of the hull. There are no integrated fuel tanks, just a flexible pipe fed into whatever portable fuel container comes to hand.

The fishing techniques are varied but the standard double outrigger configuration seems to preclude the extensive use of net fishing as setting and hauling nets around the protruding amas is tricky. Line fishing is the most common method, trolling for pelagic fish between the reef and the continental shelf. But in the last decade a new technique has emerged, putting divers in the water at night with improvised spear guns and water proofed spot lights.

Riding along the coast of Palawan, one island amongst the thousands in Philippine archipelago, around every headland a fishing village appears through the palm plantations. By any ‘western’ metric these are poor people, vulnerable to the changing climate and the glossy promises of developed societies. Fast food, fast motorbikes, karaoke and aircon are the aspirations.

As my scooter purrs through another community, reliant on the sea for generations, it seems less surprising that the Philippines is the world’s top supplier of seafarers to the global merchant fleet. These workers are crucial in keeping the Philippine economy afloat. In 2022 Filipino seafarers sent home USD6.14 billion to their families. Most of these workers come from the myriad fishing communities dotted around the coastline. Their affinity with the sea, their ability to endure hardship and their desire to escape rural poverty makes them easy fodder for the global merchant fleets.

As a participating member of one of the worlds most affluent societies, the tendency is to romanticise the lives of those who rely on the sea for base level existence… “How beautiful it would be if sails could return to these boats”… “How sad that their craft are held together with nylon rather than copra”… But this is unhelpful thinking.

Perhaps we should be more concerned about helping develop techniques and materials that allow their century old fishing traditions to continue, while preserving their environment for their children and grandchildren.

Smoko time, preparing tea and rice on a simple charcoal burner.