Baptism of Fire

Adapted from Graham Cox’s Last Days of the Slocum Era, Volume Two.

By this time, I’d already made my next mistake. Having given the ferro-cement hull to my friend, Scott Mitchinson, I purchased an old, 22’ strip-planked yacht called Mudshark. The previous owner named the yacht after his favourite Zappa song, Mudsharks in my Motel Room. It’s not a song I recommend playing to your grandmother.

I was impatient to get afloat again, having yet to learn that there are no short-cuts worth taking. In hindsight, I can see that I would have got sailing quicker if I’d saved up longer and bought a decent boat, or better yet, built that 28’ steel-hulled gaff cutter that Harry designed for me. Those drawings still stir my imagination. If you are going to buy an old boat to rebuild, at least make sure it has good bones.

Mudshark was a tired, neglected, bermudan cutter that had done a lot of cruising. It was flush-decked with reverse sheer, the prototype for the solidly-built fibreglass Tasman 22, designed by Joe Adams. They were intended for JOG racing, and had a reputation as good sea boats. It could be described as a pregnant Trekka, though it was a lot uglier. Not many designers had the eye for a boat’s lines that Jack Laurent Giles did.

It cost more money, and took longer to complete, than I could have ever imagined. That’s a story as old as Job. At times, I wondered if I would ever escape back to sea. From Monday to Friday, I’d get up at 5.30 am, row my dory across the river from Dangar Island to Brooklyn, after a quick breakfast, catch the 6.35 am train to work, and get back to my boatshed at 7 pm. Then I’d have to get up early every Saturday and Sunday, row across the river again, and go to work on Mudshark. Sometimes I looked at the boat and despaired, and in the early days, it was a grim sight. I was not only time-poor, but being on the minimum wage meant that I often had insufficient funds to buy materials.

The transom is out and things are looking shaky.

I first put a new deck on Mudshark, as the old, unsheathed plywood deck had rotted under every fitting. I laid bevel-edged, 50mm by 12mm western red cedar planks fore and aft over the existing deck beams, which were still solid. Then I added a layer of 4mm marine plywood, bedded in thickened epoxy resin, and sheathed that with three layers of 6oz glass cloth and epoxy. I varnished the underside of the deck and painted the deck beams in what became Mudshark’s signature colour, a pale cream called parchment, in which shades of peach are revealed in low light. The new deck was beautiful, light and expensive.

Because there was extensive rot in the cockpit as well (not to mention the transom), I took the opportunity to remove it entirely and build a flush deck aft, as Robin Lee Graham had done on Dove in Durban, in 1968. I had always wanted to do that to a boat, after watching Robin transform Dove. This not only provides more buoyancy aft, and room below decks for an excellent double bunk, but it removes the risk of tripping in the cockpit when reefing or furling the mainsail. This modification was an outstanding success. Sitting between custom-designed deck boxes, with my back against one and my feet braced against the other, was very comfortable.

Lounging in the cockpit between the deck lockers was very comfortable.

Then, to my horror, I discovered extensive rot beneath the Dynel sheathing in the strip-planked hull. I gazed sadly at my new deck, all A$1500 of it, a lot of money in 1985. At this point, the brother of Neill Ross, a new friend who was helping me, asked if I wanted another hand. I said, “Yes please,” and he pulled a box of matches out of his pocket. It was cruel, but probably good advice. Burning the boat at that point would have saved me a lot of time, money and sweat.

Mudshark in the tent

Biting the bullet, I dropped the keel, turned the hull over and heavily glassed it, following instructions from the book by Allan Vaitses, Covering Wooden Boats with Fibreglass, essentially building a fully-structural fibreglass hull over the old, strip-planked timber one. A lot of traditionalists pale at this idea, but it seems to me an ideal way to save an old timber yacht if you don’t have the skills or funds to rebuild it traditionally; provided, of course, that it’s not a National Treasure. Shirley Carter sheathed her famous Vertue, Speedwell of Hong Kong, in epoxy and fibreglass 30 years ago, National Treasure or no. The two of them are still happily cruising, and Speedwell is now 72 years old. Shirley further put traditionalists’ noses out of joint by converting Speedwell to junk rig. At least Mudshark wasn’t a famous Vertue, and nobody was going to start howling about my rebuild.

At times I thought the work would never end.

Then I threw away the concrete keel. It had a large crack in it, which had been hidden beneath the Dynel sheathing, and the mild-steel keel bolts had wasted away to a quarter of their original diameter. How Mudshark had sailed south from Queensland the year before I bought it without the keel falling off is a mystery. I made a new keel from hardwood and lead, bolted and heavily glassed into the hull.

I also built a new rudder and skeg, as the old one was beyond salvage, surprise, surprise, and took the opportunity to move the rudder to the transom, as I believe transom-hung rudders are the best type for offshore cruising. That allowed me to put a trim tab on the trailing edge of the rudder, connected to a horizontal-axis windvane. It was an unknown brand of commercial self-steering gear, as far as I could tell, but a lovely piece of kit.

I also put a new interior in the boat, albeit a simple one. There was nothing left of the old interior apart from the bulkheads. I had some 100mm bevel-edged kauri planks that I used for panelling bulkheads, and fitted a level platform in the main saloon, which gave me plenty of space to lounge around. My portrait of Joshua Slocum was hung on the bulkhead to port, and the painting of the Spray that I had commissioned to starboard.

Mudshark's open-plan cabin finally finished.

Coming home to the Hawkesbury River after work was always a thrill. I'd get off the train and my nostrils would be assailed by the pungent, salt-laden scent of the ocean, for the river is really, at this juncture, an estuary. It was a smell that always washed away the cares of my day. The distant, sandstone cliffs of Little Wobby, glowing orange in the evening light, reflected in the dark green river, and I tingled with the anticipation of rowing my dory across to Dangar Island. Every day was a micro voyage, and the island a magical refuge. It kept my dreams alive and made the inconvenience of living there worthwhile.

One day, in March 1989, as I walked across the pedestrian overpass from the train station, I saw a small, blue sloop anchored off the point near the public swimming enclosure. I recognised it immediately as one of the legends of the ocean voyaging world, the 25’, flush-decked Folkboat, Jellicle, sailed by Mike Bailes. I'd seen photos of Jellicle in friends' logbooks, and heard stories about Mike on the sailor's grapevine.

Mile Bailes aboard Jellicle in Whangarei, NZ, 1991.

Originally from England, he had sailed his little sloop more than 85,000 miles over the previous 30 years, nine times across the Atlantic and countless times around the South Pacific, usually with just one young man as crew, all without the benefits of engine, electricity, or any other modern conveniences. In his late sixties now, scruffy, short and unprepossessing in appearance, he was an intensely shy and private man who shunned publicity.

I went aboard Jellicle and spent some time with Mike and his crew, 19-year-old Andre, who was the son of another famous ocean voyaging couple, West Indians, Harold and Kwailan La Borde, from Trinidad, who were friends of Mike’s. I had read their book, An Ocean to Ourselves, when I was just a teenager myself. Jellicle was scruffy and dirty, and beneath the flush deck, the cabin seemed minuscule, but the basics were sound, including a bullet-proof rig. As Mike said, ‘When sails are all you've got, the mast, sails and rigging need to be beyond doubt.’

The boat was exactly the sort I had wanted as a boy, and Mike had led the life I'd dreamed of. In some ways, sitting there, I felt a failure, for so many years had passed, but in another way, I was electrified. Mudshark was not much smaller than Jellicle, with the same, seaworthy, flush deck. No boxy cabin to get knocked off by waves. When I'd finished rebuilding the boat, it would probably be stronger than Jellicle.

I chose to install a simple electrical system in Mudshark, powered by a small solar panel, rather than rely exclusively on kerosene lamps, as I had in the past, plus I added my first-ever radio transmitter, a line-of-sight VHF unit, very handy on the coast. I jokingly claimed I was getting soft, but later discovered that there were limitations to my setup.

I also fitted a low-powered outboard motor, another first, for convenience when manouvering in harbours. Because of the outboard rudder, the motor had to be mounted on the starboard side of the transom, which limited its usefulness. Mudshark was essentially engineless at sea unless the ocean was smooth.

Mudshark was relaunched in March 1992, a few weeks before my 40th birthday. My immediate impulse was to quit work and sail away, but my friend, John Murray, who'd circumnavigated out of Sydney between 1969-75 on his home-built trimaran, Unbound, persuaded me to stay in the public service and wait until I was eligible for long-service leave.

Mudshark about to launch after almost a decade rebuilding.

Then I could take eight months off work and sail up to Queensland and back, before deciding what to do next. If it all went as planned, and I decided I was ready for that great, open-ended voyage I had always dreamed of, I could resign and sail away. If not, I would still have my job. In the meantime, I sailed Mudshark around the Hawkesbury River and down to Sydney Harbour, getting to know the old boat again.

The great day finally dawned. At the age of 42, I was setting off on my first extended solo cruise. I would have mocked you if you’d told me that when I was 16. It was only up the coast to Queensland, but you can drown just as efficiently 10 miles off the coast as you can when 1000 miles out. Given the amount of shipping, adverse current, river bars and rocks one encounters on this coast, it might even be easier.

Mudshark sailing on the Hawkesbury River prior to departure.

I’d spent the previous month feverishly preparing Mudshark in front of Charlie Hill’s waterfront house on Dangar Island, where I could put the boat alongside his jetty at high tide. Careened against the stone wall, I gave the topsides a final coat of paint and antifouled the bottom. I thought I would be ready to go at the beginning of April, but the work list seemed to have a life of its own.

I began to run short of funds, yet again, but some of my friends offered generous assistance. The late Bella Szudrich loaned me $1000 without being asked, and Rex Byrne gave me an inflatable Avon Redcrest dinghy, to which I’d fitted emergency inflation via two compressed-air bottles. It was lashed on the foredeck.

I also had a full set of paper charts, two hand-bearing compasses, as well as the ship’s compass, and a Garmin 45 GPS, the first such unit I’d owned. It was primitive by modern standards, but provided me with continuous latitude and longitude coordinates. Combined with my traditional physical navigation skills, it was an excellent tool.

After so long, I couldn't wait to get aboard!

Mudshark left the Hawkesbury River on 8 May 1994. As I went down the river, I heard a strong-wind warning on the VHF radio. I could expect 25 knots from the SE by nightfall. I wanted to duck into Cowan Creek for the night and leave the next morning, refreshed, but some of my friends, accompanying me on another yacht as far as the ocean, shouted encouragement to keep going.

I should have ignored them. All my life, I have been too easily influenced by other people’s opinions. It was the last time that I have ever announced my departure. For the next 25 years, I deflected questions about when I planned to leave, just slipping away when the weather suited. I’d seen seasoned voyagers do that, and now I understood why. Another reason for slipping quietly away is that departures cease to be an event and become just a part of life.

Looking happy as I finally depart.

By nightfall, it was blowing a moderate gale. Sitting on the flush deck between the angled cockpit deck boxes, with my back against one and my feet against the other, I felt surprisingly secure, as Mudshark plunged into the rising sea, but I was anxious. It looked like a long, dark and dirty night ahead. We were close to the coast, and in a major shipping lane, so sleep would be impossible.

Then a wire cable in my self-steering gear broke. It was one of the few things I had not renewed before departure and was not critical to safety. It should not have precipitated the crisis of confidence it did. Part of the problem was that Mudshark’s rebuild had been somewhat unconventional, and I could not draw on precedent for comfort.

The sun plunged behind distant hills, taking the last of my spirits with it. I was forced to spend the night on deck, steering. The wind went easterly and rose, I discovered later, to 35 knots, with frequent rain squalls. I clawed down the mainsail and continued with just the high-cut Yankee jib. Even this sail was too much, and Mudshark was dragging its chainplates in the water at times, but I was reluctant to go up onto the foredeck to change sails. It looked like an exposed ridge on a gale-racked mountain up there.

The night that followed was harrowing, though in retrospect, there was nothing much to worry about. I’d never considered how much strength I drew from the presence of others. I was discovering that sailing alone is psychologically challenging. I had meticulously prepared the boat, but I was not mentally prepared for singlehanded sailing.

Some of the wave crests struck Mudshark with brutal force. To seaward, several ships passed by. I gazed longingly at their lights, imagining the certainty, the warmth, and the companionship in those cabins. To the west, I could see the loom of various settlements as we passed by. Knowing the coast as well as I did, this allowed me to keep a rough reckoning of progress, and by staying east of the rhumb line, I knew I would hold clear water. I did not go below to plot my position on the chart. At times, the moon appeared briefly through the black clouds, casting a cold beauty over the scene. And it certainly was cold. It felt as if my marrow was freezing.

At dawn I recognised the hills behind Port Stephens. Daylight snapped me out of my catatonic state, and I leapt into the cabin to verify my position with the GPS unit. When I left the tiller, I discovered ruefully that Mudshark would steer itself to windward without my assistance. I could have sat in the warm cabin all night.

It seems quaint now, how thrilled I was with a gadget that would give me latitude and longitude readings 24 hours a day, updated every few seconds, that I could then transfer to my paper charts and plot a new course. I was 10 miles to seaward of the entrance, exactly where I wanted to be. Two hours later, I surfed in through breaking waves into sheltered water, and was soon securely moored in Nelson Bay. There was a marina where Rex and I had previously tied stern-to the public wharf in 1979, on our voyage north in the Hunter 19, Mistral. It was expensive, but I enjoyed the security of an all-weather berth, falling into a deep, sweet sleep.

I took off again one week later. I had repaired the self-steering system, sorted out my gear, and meditated on the joys of solitude. I was still uneasy, but determined to try again, watch the weather and leave when I was ready.

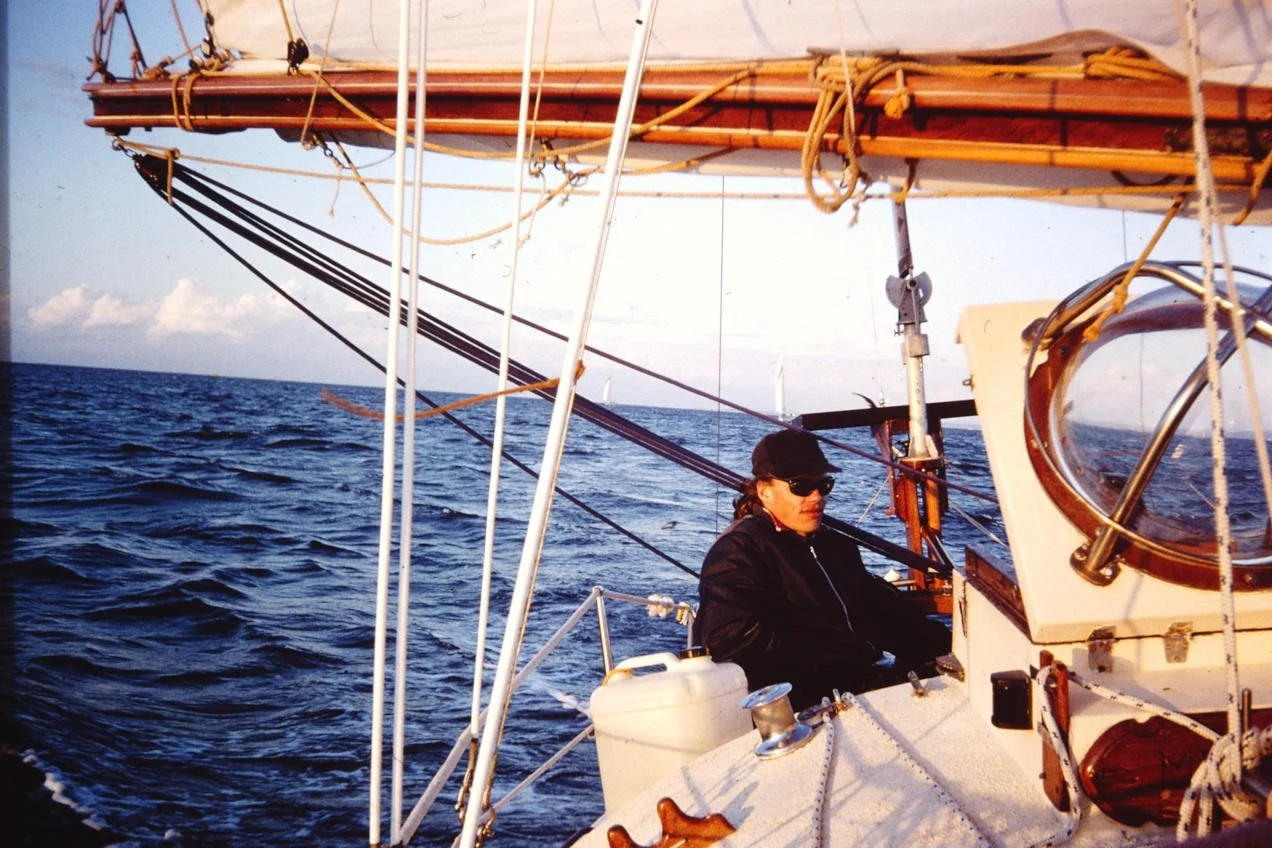

Going well under main and genoa in light winds north of Port Stephens.

Paradoxically, when I did leave, the winds were too light, and I found myself longing for a small diesel engine. The alternative, of course, would be to fly light-weather sails - drifters with the wind forward of the beam and spinnakers when it is aft - which is what Messrs Tangvald, Carr and Pardey, some of my voyaging heroes, would do. I did have a beautiful, yellow-hued drifter, but rarely set it at sea, being both lazy and too anxious about getting it down in time.

The sea was like a lazy river. The only blot on the landscape was a securite message on the VHF radio, reporting a large, drifting, steel object NE of me. What did that mean? Was it coming my way? I tried calling on the VHF for further information but received no response. So much for the added security of two-way radios. I kept a leery lookout but was relieved not to see anything.

By judicious use of the outboard motor, which was useless in any chop or swell but fine on this gloriously flat ocean, I made it to Seal Rocks just before dark, anchoring well off the beach in 7m of water, according to my lead-line. Mudshark had no electronic echo-sounder. Another limitation to motoring was that I only had 25 litres of petrol, in a stainless-steel tank mounted in teak chocks on the afterdeck.

There were a few fishermen on the beach, hauling a boat up out of the water with the aid of a tractor. They watched me curiously as I stowed the sails, and I gave them a nonchalant wave, like a true South Seas vagabond, though I felt a bit fraudulent. Fake it till you make it. Mudshark rolled gently in a low swell all night, and the surf growled on the sand. This place could be a death trap in a sudden onshore gale, but the forecast was good and I slept well.

By noon the next day, I was sailing in a moderate SW wind and bright sunshine. Because the wind was off the land, the electric-blue seas were easy, and the ocean swell, usually from the SE on this coast, was also slight. The Brother Mountains were clearly visible to the north of Cape Hawke. I was tempted to go into Cape Hawke Harbour, where I had spent some time in 1973, but decided to press on.

Unfortunately, the wind died later, and then came in from ahead, so I began the laborious task of tacking against it. I had the genoa up, and Mudshark was going well, making four knots through the water, with finger-tip steering, although the windvane was doing the work. Little boats love light winds, if the sea is also slight.

Night fell as I tacked in towards Harrington Inlet, out towards the dark horizon, which was busy tonight with a parade of ships, in again before reaching the shipping lanes. Would I ever pass the bloody place? Out again, noting with relief that the wind was swinging from NE to N then NW, allowing me to hold the course.

The battery was flat, and without a means of charging it, I was sailing without electric navigation lights or VHF radio. I had a small solar panel on the stern, below the windvane, but on this northerly heading it was always shaded by the sails. It was almost winter now, and the sun was well to the north of my latitude. I tried lighting my backup kerosene lamps, but they wouldn't stay alight, even in this moderate breeze.

The lamps looked the part, but they were obviously an inferior design to those used by old-time sailors. I'd read that the old lamps had inner glass cones to protect against drafts. I even had an article on board, written by Larry Pardey, describing how to retrofit them, but hadn't taken advantage of this information.

It was 0200 before I rounded Crowdy Head, crept past unlit Forde Rock, blessing my GPS, and lined up the leading lights into the Boat Harbour. I’d noted the latitude and longitude of the rock on my paper chart, then made sure my GPS coordinates stayed well outside those parameters, a modern take on clearance bearings.

Mudshark moored in Crowdy Heads

Inside the harbour, I was shocked by how small it was, and uneasy about the ever-present surge that slammed vessels back and forth along the public jetty. I had a little plank to put outside my fenders, but it was too short, and Mudshark's hull smacked heavily into the pilings, knocking paint off every time it did so. After a few clouts, I pulled away, put down an anchor and took a line ashore, pulling the yacht as close in to the jetty as possible, but far enough off to avoid damage. Within hours of my arrival, a strong southerly gale developed, trapping me in port for three days.

It was a picturesque place, a small settlement scattered prettily up the hill overlooking the harbour, but I was unhappy there. Every day, local fishermen came by to tell me that I shouldn't be anchored in that position, that I was restricting access to the slipway, and that if there was an emergency, they would undo my boat and let it go. I explained my situation, assuring them that I would be aboard at all times, but they were unimpressed.

‘Shouldn't be out there if you're not properly prepared,’ one said. ‘People like you are a menace.’ Some trawlers, I felt, were deliberately steering to pass Mudshark closer than they needed to. My sense of alienation, always high, peaked there.

When the weather eased, I was out of that place like a rabbit out of a hole. The wind was still fresh from the south and the seas were running high. Mudshark hurried northwards, with the mainsail vanged out one side and jib poled out the other, self-steering with the windvane. We were making good progress, but at a price, because the yacht rolled heavily with the wind right aft, and the wind direction kept varying slightly. I had to gybe the mainsail and reset the jib on the other side repeatedly, trying to stay on course. Even though the weather was beautiful, exhaustion began to hover in the wings.

Just after dark, the anchor went down in Korogoro Bay, 10 miles south of Smoky Cape, another open roadstead with the sea growling on the beach. I was stupid with fatigue, and accidentally dropped my anchor mate, a lead weight used to hold down the anchor rope, plus my favourite beanie, over the side. That night I slept heavily.

Not having a functioning radio, as the battery was still flat, meant no weather forecasts, and I’d been too stupid to bring a transistor radio receiver as a back-up, but luckily the weather remained calm. There’d been no way to charge the battery at Crowdy Head, and once again, the solar panel had been shaded much of the time.

The next day I took off for Coffs Harbour. The passage took 20 hours, tacking against 15-knot NE winds all the way, after a light start. Mudshark went well, with one reef in the mainsail plus the genoa, and the self-steering gear doing most of the work. My major task, besides navigation, was to look out for ships once night fell. Because of the flat battery, I was sailing unlit and in radio silence. I felt the lack, but reminded myself that John Guzzwell didn’t have a radio or electric navigation lights on Trekka, and he fared perfectly well.

After all that hard work, sailing on the ocean was a joyous experience.

Every now and then I had to dodge a handful of spray that flung itself across the deck, but the sea was quite reasonable, the black-velvet sky was bright with stars, and the moon was almost full. Lovely sailing, but I admit to suffering from a certain amount of anxiety and loneliness. The NE breeze died in the early hours of the morning, leaving me slopping about in a leftover swell for half an hour, until the seas died down enough to use the outboard. I then puttered into Coffs Harbour and tied up in the marina.

I spent over a month in Coffs Harbour. I had fallen in love with this congenial place in 1979, and once again time passed easily. The little harbour juts out into the sea, and it is a snug feeling, lying in your berth with the waves growling on the other side of the breakwaters. It is like being held in the bosom of the ocean. There is a beautiful beach just north of the harbour, with the untiring spectacle of young surfers elegantly riding the waves, and imposing mountain ranges rising in tiers to the west. One of my favourite walks was to the top of Muttonbird Island, near the entrance. Rex and I had scrambled up there in 1979, dodging muttonbird burrows in the long grass, but in 1994 there was a paved walkway all the way up.

Mudshark sailed for Ballina on 6 July. It was good to be at sea again and I felt lighthearted. Winds were slight, and remained so during the 24 hours it took to reach our destination. I had a friend on board, Tim, a novice sailor who was mildly seasick and slept mostly, but I didn't mind. In this calm weather, exhaustion wasn't an issue, and it was pleasant to glance down through the hatch and see Tim curled up on his bunk. How extraordinary it was, the strength I drew from that prone figure. Later, he recovered and came up on deck to enjoy the sunshine.

Tim steering north of Byron Bay.

The bar at Ballina was just starting to break when we surfed across it the next morning, an hour after high tide. It took some days before the bar was calm enough to get back out to sea. Our plan was to anchor for the night at Byron Bay, but the wind, despite a favourable forecast, soon came up from the north and strengthened. There is no shelter from northerlies on this stretch of the coast. In retrospect, we should have stayed at sea, it would have been safer, but northerlies usually calm down during the evening. With no warnings being issued on the radio, I assumed it was just the usual NE seabreeze.

We anchored in the bay just before dusk, but, instead of easing, conditions continued to deteriorate. The boat was flinging itself around, jerking wildly on the anchor cable, and we both felt seasick. The open ocean, with no moon or stars visible, looked like a black hole, a vortex that could suck you into oblivion. The radio now reported an unpredicted low passing across the coast north of us, but luckily it wasn't too severe. The wind was only 25 knots, but the sea quickly rose to more than 1m in the bay. Every couple of hours, a police car drove down to the beach and shone its headlights on us, obviously concerned for our safety. Each time, I’d give them a shaky wave.

Tim retreated below and I sat on deck, worrying that the anchor might drag, or the cable snap. We'd have been on the beach in minutes unless immediate action was taken. I had already double-reefed the mainsail and hanked on the storm jib, in case we had to sail out, as I explained to Tim.

‘Sail out where?’ he demanded.

‘Out to sea. If things get worse, we may have no option.’ This was the accepted wisdom of the old salts; if in doubt, clear out, assuming one has confidence in oneself and one's vessel, of course. I was not too sure about either, but would have done it before losing Mudshark.

Tim looked seawards with a wild look on his face. ‘I don't want to go out there,’ he said emphatically. ‘I want to go ashore.’ He looked longingly at the beach, where the lights of the hotel blazed. I had no desire to go out into that black hole either; sometimes I think the whole purpose of voyaging is to rediscover the beauty of the commonplace. I prayed the anchor would hold.

At 0300, the wind died away, and I crawled thankfully below. At 0500, when I looked out again, there was a moderate SW wind blowing off the beach, and the sea was flat. How quickly things can change at sea. I jumped up and hoisted the mainsail quietly, then brought home the anchor before raising the jib. Mudshark fell off and began sailing fast, just off the beach.

When Tim woke a couple of hours later, we were well on our way to Southport, reaching in bright sunshine across a smooth, vividly blue sea. Being so close to shore allowed us to enjoy the unfolding scenery. The beach was magnificent, mile after mile of pristine white sand dunes, unspoiled by development or pollution. We were both happy that day, lolling on the deck. I hoped it might convince Tim to stay with me and sail on to the Whitsundays, but he went home from Brisbane. If you don’t have a passion for ocean sailing, it must seem like a stupid way of life.

Mudshark sailing fast

After visiting old sailing friends at Manly Boat Harbour in Moreton Bay, I set sail a few days later, bound for Mooloolaba, one of my favourite places, via Tangalooma on Moreton Island, where I spent an uncomfortable night anchored behind the wrecks, rolling in the swell from a light offshore winter westerly breeze. It was cold, too. Arriving in Mooloolaba the following day, I took a berth in Lawries Marina, now known as Kawana Waters Marina, and somehow ended up staying there for the rest of the winter.

That brought my first solo cruise to an end, but it laid the groundwork for the next 25 years of extensive coastal cruising, mostly solo, between Sydney and Cairns. And the story is not over yet. Although I am now 72, I hope to set sail again in May 2026, heading back to the Whitsundays and beyond, aboard a small junk-rigged yacht I have planned. Currently, I am based in Mooloolaba aboard my 1974 Cavalier 32, Mehitabel (it is for sale), busy with various writing projects, including my recently published sailing memoir / selective history of ocean cruising since the 1960s, Last Days of the Slocum Era, Volume One and Two, plus my upcoming weekly written commentary on the Mini Globe Race.