Bass Strait Seal Mania

By Russel Kenery

The Australian fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus),

the world’s largest, weighing up to 300 kg

Thirty years before Batman arrived in Port Phillip, Western Port became ground zero

of a colonial seal rush.

In 1797, George Bass coasted south from Sydney in a 28 ft naval whaleboat with six crew. After rounding Cape Howe onto the southern coast, Bass discovered a big bay he named “Western Port” because of its position relative to Port Jackson. Bass reported the southern coast and islands were teeming with seals and predicted a colonial sealing industry.

The following year, Bass teamed up with Matthew Flinders in the 35 ft colonial sloop NORFOLK for their epic circumnavigation of Van Diemen’s Land. They departed Port Jackson in company with Charles Bishop in the NAUTILUS, who was heading south to hunt seals in the Furneaux Group at the eastern end of what Flinders would call Bass’ Strait. Bishop caused a sensation when he returned to Sydney with 5,200 Australian fur seal skins and 350 gallons of seal oil. It created a sudden mania that doomed the seals of Bass Strait to near extinction.

Sail-in sail-out sealing in the Bass Strait became the primary source of wealth for the infant Colony. A fur seal skin could fetch 5/- (double the average weekly income) and 1/- for a gallon of oil. The sealskin and oil trade values were soon far greater than the Colony’s total agricultural output. The seal’s only predators were large sharks and killer whales, so on land, men quietly strolled among the seals as they lanced and clubbed them to death. Gangs of sealers soon decimated the enormous rookeries of Western Port, even slaughtering cows and pups.

Bass Strait Sea Rats – Hard Men in Small Boats.

But, as early as 1804, Governor King wrote to Lord Hobart in London of his concern that the ungovernable industry might drive the seals away. He reported that the colonial industry had harvested 107,600 seals in the previous 12-months alone. Also, American ships were “continually among the islands in & about the Bass Strait for skins and oil, thereby greatly inconveniencing His Majesty’s subjects.” The Nantucket whaling ship, FAVOURITE, had recently sailed from Sydney to the Bass Strait sealing grounds and unloaded 87,080 fur seal skins in Canton. King’s gloomy prognostication proved correct. By 1810, declining seal numbers meant sail-in sail-out sealing was no longer viable; sealers (aka ‘Sea Rats’) became semi-permanent residents on the Bass Strait islands.

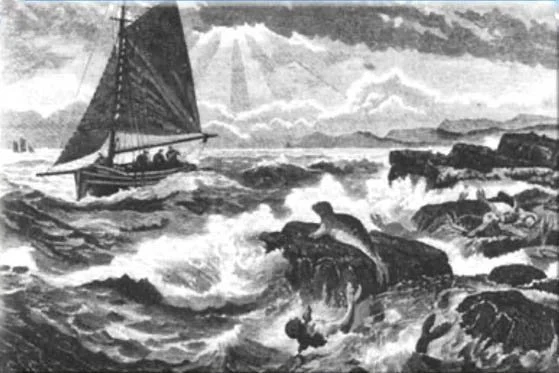

19th Century whaleboat, the craft of choice of Bass Strait’s Sea Rats.

The Sea Rats led a brutal, lawless life in tiny island settlements. Most were former or escaped convicts, military deserters, ship runaways, and a fair sprinkling of psychopaths. The modus operandi was small boats putting Sea Rats ashore with provisions on the Bass Strait islands and sea stacks to harvest seals and prepare the skins. Sometimes, the boats never returned because of storms, shipwrecks, or forgetfulness. The body of one Sea Rat lay for years among seal skins in a cave on Black Pyramid Rock off Albatross Island. Even though long dead, salty sea spray had preserved his appearance as if freshly laid out for burial. The sailors who found him were disturbed for years afterward. Many Sea Rats joined or tried to stow away on American whaling ships to escape the mayhem and getaway to anywhere outside Australia.

In 1830, George Frankland, Van Diemen’s Land’s Chief Surveyor, recorded,

“In consequence of the reckless and improvident system of destruction followed by the seal hunters, the valuable animal is nearly extirpated from our neighbourhood.”

By the time Batman settled on the Yarra River in Port Phillip, the colonial sealing industry had wiped itself out. Thirty years of unrestrained greed killed at least two million fur seals. A staggering 1,000 tons of Australian sea lion oil came off King Island alone. Today, it’s believed the total number of Australia’s fur seals and sea lions are at most 1/10th of the crudely estimated pre-1790 population.

Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea). Pre-mid-19th Century, sea lions were common along the southern coastline. Today, they’re found only on the Pages Islands off South Australia and the Houtman Abrolhos off southwest Western Australia.