Classic Performance - Part II

In this second piece by Ian Ward we look at the

PERFORMANCE & HANDLING

of Classic Yachts compared to their modern counterpart.

Anecdotes

There is something quite magical about how classic yachts such as 5.5, 6, 8 metre and 30 sqm class yachts glide gracefully in light air, while boldly pointing high to windward as they heel gunwale down in a breeze, with little fuss and often a well-balanced helm, they exhibit an ease of handling mostly unmatched by their modern counterparts.

Witnessing with appreciation, as Caprice of Huon in a veterans regatta easily outpacing the latest 40ft Beneteau, Bavaria & Jeaneau designs upwind in a stiff breeze. Although decidedly heavier and shorter on the waterline, she just points higher with mainsail cranked on under full control while the modern designs desperately dump travellers and flog their mainsails just to keep the boat on its feet, to prevent rounding up and broaching. Faster they may well be in light air and downwind, as they should be, but here they are no match for a true classic design where it really counts.

What a delight to behold the Classic 62sqm ‘Plym’ outpacing a modern, lighter, longer waterline and more powerful Beneteau First 45 upwind in a gusty nor’easter on Pittwater. Gunwale down, making ground to windward at full pace in the gusts, fully under control with a light touch on the helm!

Then there is pure joy in witnessing the classic 6 metre Rendezvous consistently outpacing a Fareast 28R by several minutes around the course, even in moderate air. While much smaller in waterline length, and of heavier displacement, it is amazing how well these beautiful old girls perform boat for boat let alone ‘for their size’.

Steering a Dragon upwind in a stiff breeze with finger-tip helm, as it effortlessly climbs to windward and ahead of a J24, despite being both heavier and shorter on the waterline than the J24’s which gather weather helm as they heel and slide sideways in gusts.

While witnessing these wonderful displays of classic yachts outperforming lighter modern boats with their longer waterlines, “something simply just does not ring true!” How can these classics win off scratch in mixed fleets, often against ‘significantly faster’ boats of more ‘flighty’ proportions and high tech construction and yet be considered slow and outdated. How is it that the newer, lighter designs are so difficult to control when the going gets tough?

Perhaps this perception is not so much related to the design itself, its age, construction or performance, but to the changing goalposts of the rating rules and handicap methods by which relative performance is commonly judged, or perhaps it is simply due to a popular practice of comparing performance based on the overall length rather than by the fundamental proportions of the boat.

Comparative Performance

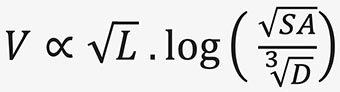

If instead of using rather arbitrary rating systems or overall length as described in PART 1, a yacht’s performance may be compared more reliably to others based on its fundamental proportions of waterline length ‘L’, sail area ‘SA’ and displacement ‘D’ which govern the available power from the rig to overcome the wave making resistance of the hull.

Extensive tests conducted on some 80 ships models in 1910 by Rear Admiral David W Taylor determined that the wave making resistance of a hull log(R) is close to being proportional to its speed (V/√L) and also varies with its displacement/length ratio.

As the resistance of a yacht is overcome by the force acting on the sails, it is possible to derive a relationship where its speed is dependent on its Displacement, Length and Sail Area.

(V=Speed , L=Waterline length, SA=Sail Area, D=Displacement)

Based on this relationship, which also varies with D/L ratio, it is possible to determine the speed ‘potential’ for any hull, against which the efficiency of different designs may be compared.

Over many years observing and comparing mixed fleet racing on this basis, there is no doubt that the newer, lighter boats do often perform better ‘for their size’ than the older designs, especially in light air & downwind. They tend to drift faster due to their reduced wetted surface area and accelerate more readily in gentle puffs due to their lighter weight and relatively larger sail area. In stronger breezes downwind, they tend to perform as would be expected for a lighter, longer hull which benefits significantly by surfing more readily on waves, especially when racing offshore.

A major difference is observed however, when sailing upwind in a breeze. Here the lighter boats tend to have a lower ballast ratio, relying on form stability and crew weight for righting moment. While often pointing higher with modern, close sheeted fractional rigs, they also tend to slide sideways, gather weather helm and round up in gusts. This necessitates flexible rigs, rapid reefing systems, large balanced rudders and the crew actively trimming the mainsheet to keep them “on their feet”. Even then, they rarely prove much faster and are sometimes even slower to the windward mark than the shorter waterline, heavier classic yachts.

Steering & Handling Perhaps the most significant difference between the older designs with their longer keels, fine hulls and heavier displacement is in the steering response, balance and handling. Traditional classic designs tend to be docile, directionally stable and perhaps slow & heavy to turn. On the other hand, they track straight, the tiller may be left unattended as they can often steer themselves and the helm is self-centring when released. Even when pressed upwind, well-balanced classic yachts do not tend to gather weather helm or gripe, some can even free sail over a wide range of conditions!

Modern designs with fin keels & spade rudders are directionally metastable. As a result, they turn very easily and are responsive to the helm, but do not readily hold a course. As the breeze builds these boats also tend to gather weather helm due to a misbalance of CE(Centre of effort) and CLR (Centre of lateral resistance) and can round up or broach due to any imbalance of the hull as it heels.

It all depends how you appreciate these qualities. Some may see it as a great challenge to actively steer their boat, feel it want turn hard around a mark, to work as a team to trim the sails as a gust 10 hits, to keep her on her feet or steer and trim to anticipate gusts to avoid broaching. Traditionalists may on the other hand prefer to have none of that, being consummately satisfied with a docile, easily handled craft with a light helm which shows no tendency to gripe, finds her own way in gusts, lifts and knocks without having to manhandle the sheets or fight the helm.

The comments of knowledgeable designers, sailors and journalists supports these observations:

Tony Marchaj - Aero-Hydrodynamics of Sailing - seems resigned to these issues; “Steering deficiencies are probably an unavoidable price one has to pay for the reduced wetted area of appendages.” Even predicting that, “The same kind of disease is bound to afflict the modern breed of cruiser racers”.

James Jermain - Yachting Monthly - observes that; “Over the years, hulls have become shallower and keels narrower, but for many types of sailing this progression is not necessarily progress”. “For windward sailing the use of a fin keel may make the boat less steady on the helm” and “There is a strong tendency to round-up when hard pressed” while “Downwind, boats with a fin keel can broach easily and suddenly or it can be directionally unstable and hard to control in heavy conditions.”

Arne Kvernland makes it even clearer, stating; “Unfortunately, these days, sailing cruisers are neither directionally stable nor have balanced hulls. Still, they are being sold as ocean cruisers. You’ll easily recognise these boats by their sharp, vertical bows, wide sterns and huge steering wheels to cope with the weather helm.” and “My worry about such boats… is that they can broach so easily. Their salesmen say that it is a part of the safety that the boat will run out of rudder and round up in a wind gust. I don’t buy it. The problem is that these hulls will also be prone to broaching when sailing downwind in a seaway. Such broaches can leave them in a vulnerable position and attitude to be knocked fully over by the next following sea. And yes, there have been a number of such accidents.”

John Rousmaniere has written over 20 books on the subject. In “Offshore Yachts” he states that; “directional stability is improved by the skeg because it acts like tail feathers well aft of the centre of gravity.” and “The dorsal-type fin forward of many skeg-mounted rudders also acts as a stabilizing factor. He also commented that “The CE/CLP balance theory is quite old —dating back at least to Manfred Curry and it may not please the modern techies with racy boats and modern fins and aerodynamics theories.”

Olin Stephens – Yacht Designer - admitted that the “separation of the rudder and keel resulted in frequent broaches on hard runs” in Clarionet and confided that he “wished that he had a method to determine hull balance” hoping that “CFD may provide an answer in the future”.

Interestingly, while observing the significant issues with handling differences between these types of boats, none of these authors or designers present a clear reason for these changes in behaviour and even recent yacht design texts tend to avoid the topic altogether.

It turns out that there are some significant fundamental aspects of the design of a yacht which determine its handling. These are greatly affected by the latest design changes towards fin keels causing directional instability and light hulls with wide sterns causing weather helm and broaching.

These issues are addressed in PART 3 of this series of article.

This Article was amended 24/09/24 following comments below from Kim Klaka.

Ian Writes…

I would like to thank Kim for his valuable comments and to apologise for an unintentional error, which he has identified, relating Taylors series to sail area, which was incorrectly expressed. This has now been corrected. If Kim has a source for relevant data for the speed potential of yacht hulls for varying Displacement, LWL and Sail Area, this would be most appreciated.

1) As Kim points out, classic yachts are typically under canvassed. If speed for overall length is the basis of assessing performance, then any over canvassed boat which is also lighter and longer on the waterline should of course be significantly faster. In this article I have focussed on comparing performance based on the fundamental proportions governing the speed of the boat ie: D, L & SA which can often tell a different story, as classic yachts can indeed outperform by this measure.

2) I have been careful to separate the issues of upright directional stability, influenced by a fin keel and any imbalance of the heeled hull leading to weather helm and broaching. This is explained in some detail in the following parts 3 and 4 of the article.

While length/beam ratio may provide a broad guide to better manners, it is still possible for a narrow hull with fine bows and a relatively wide stern to gather weather helm as they heel and to broach, including some classic yachts.

Kim may be surprised to find that model yachts such as the DF65 are held in unstable equilibrium, relying on the rudder being locked centrally to hold a course. Release the helm, allowing the rudder to turn freely or remove it altogether and the boat is directionally unstable. Push it backwards however, and it tracks perfectly straight.

3) As Kim points out, the quoted comments relate primarily to yachts which were modern some 40 years ago. The point of this article being that classic yachts often do not suffer these same vices. If the fundamentals governing steering and broaching were properly understood at the time, why have yacht designers subjected owners to this poor behaviour over the past half century? The purpose of this series of articles is to explain what causes these issues and how to avoid them, so designers can optimise both performance and handling instead of relying on what appears to be trial and error.