Flinders Adjuncts

Some of the 487 people (so far) who have read about Russell Kenery’s monograph “Matthew Flinders-Open Boat Voyages” might be interested in his follow up correspondence…

Russell writes

The little publication proved to be a satisfying & worthwhile project for the Flinders Yacht Club. Availability these days is at the Flinders Post Office, but it can also be bought from the Flinders Yacht Club, Commodore, info@flindersyc.com.au and from the excellent Bass & Flinders Maritime Museum, George Town, TAS Phone (03)6382 3792 www.bassandflindersmuseum.com.au

Flinders Yacht Club

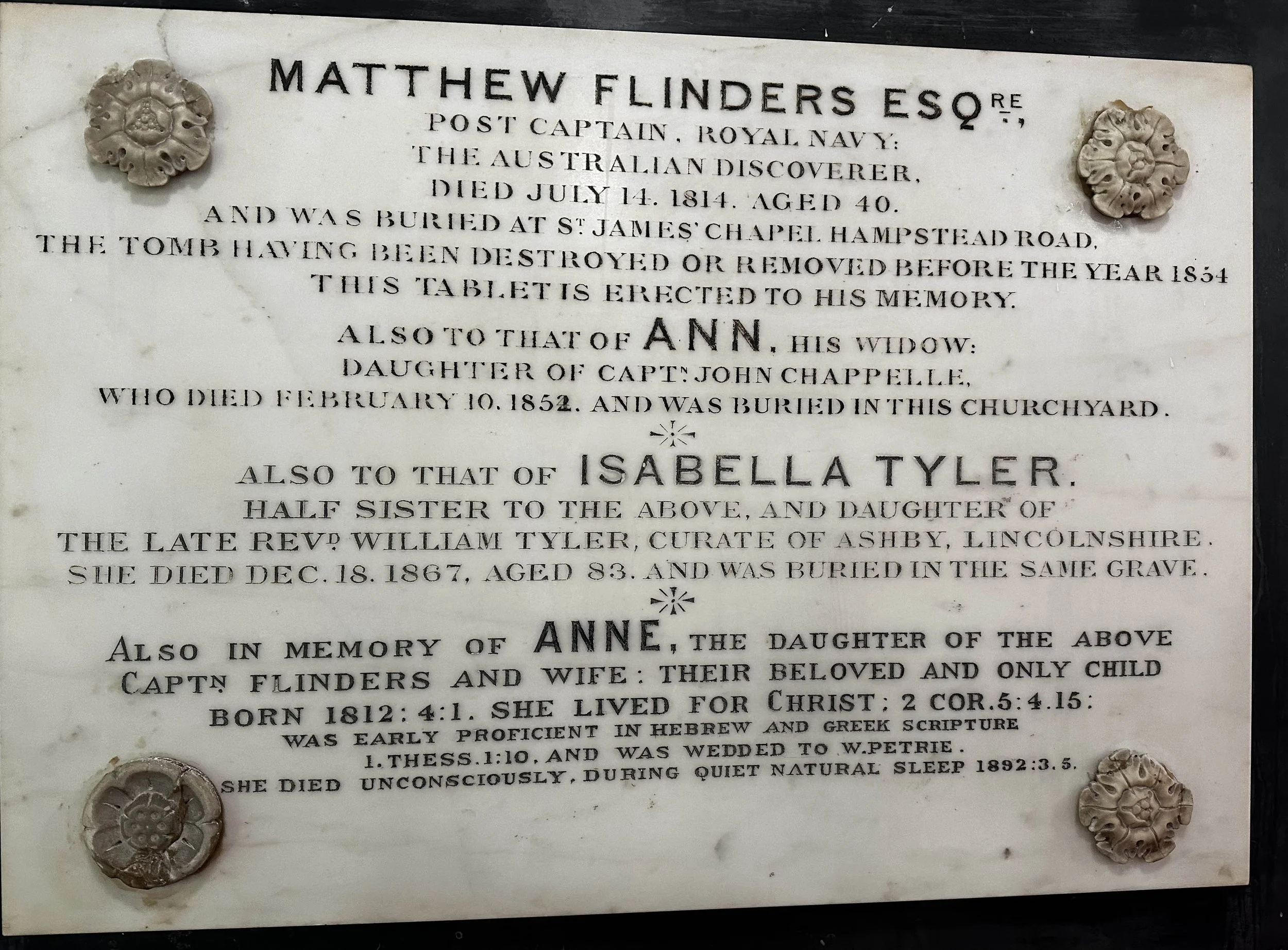

Speaking of Flinders, as you’ll likely know, this year, 2024, was memorable for Matthew Flinders. He had his 250th birthday, and on 14 July, he returned home to Donington, having been lost for 165 years. We know Flinders as a significant historical figure, but few know he died in obscurity. The British Admiralty didn’t appreciate his achievements. His family received no pension, and his widow Anne had to pay for a memorial tablet at St Thomas Church, Southwark, London. Why so? I suspect a few reasons. Flinders had been held captive by the French for 6 ½ years; he died young at 40 [James Cook’s age when he set out on the 1st of his three voyages of discovery], and he was a modest man. In all his exploring and charting, he named nothing after himself. Also, when he eventually returned to England [his health ruined, his Navy career over], he found that the French had put French names on many of his discoveries.

When Flinders died, he was buried in the St James Burial Ground in London. However, 30 years later, Euston Railway Station expanded into the cemetery, destroying 40,000 tombstones [including Flinders’]. Ten years ago, archaeologists excavated the old cemetery site before Euston’s reconstruction began for London’s Eurostar Station, but identifying one skeleton from the other 40,000 was impossible without the headstones. Flinders got lucky. One of his friends had donated a lead plate for his coffin lid which was inscribed, “Capt Matthew Flinders RN. Died 19 July 1814. Aged 40 Years.”

On 14 July this year, he was returned home to Donington – and reinterred in the church where his grandfather, father, and brother are buried. Margie Brophy of the Bass & Flinders Maritime Museum in Tasmania attended the service in Donington.

Church of St Mary and The Holy Rood, Donington- Image Steven Granville

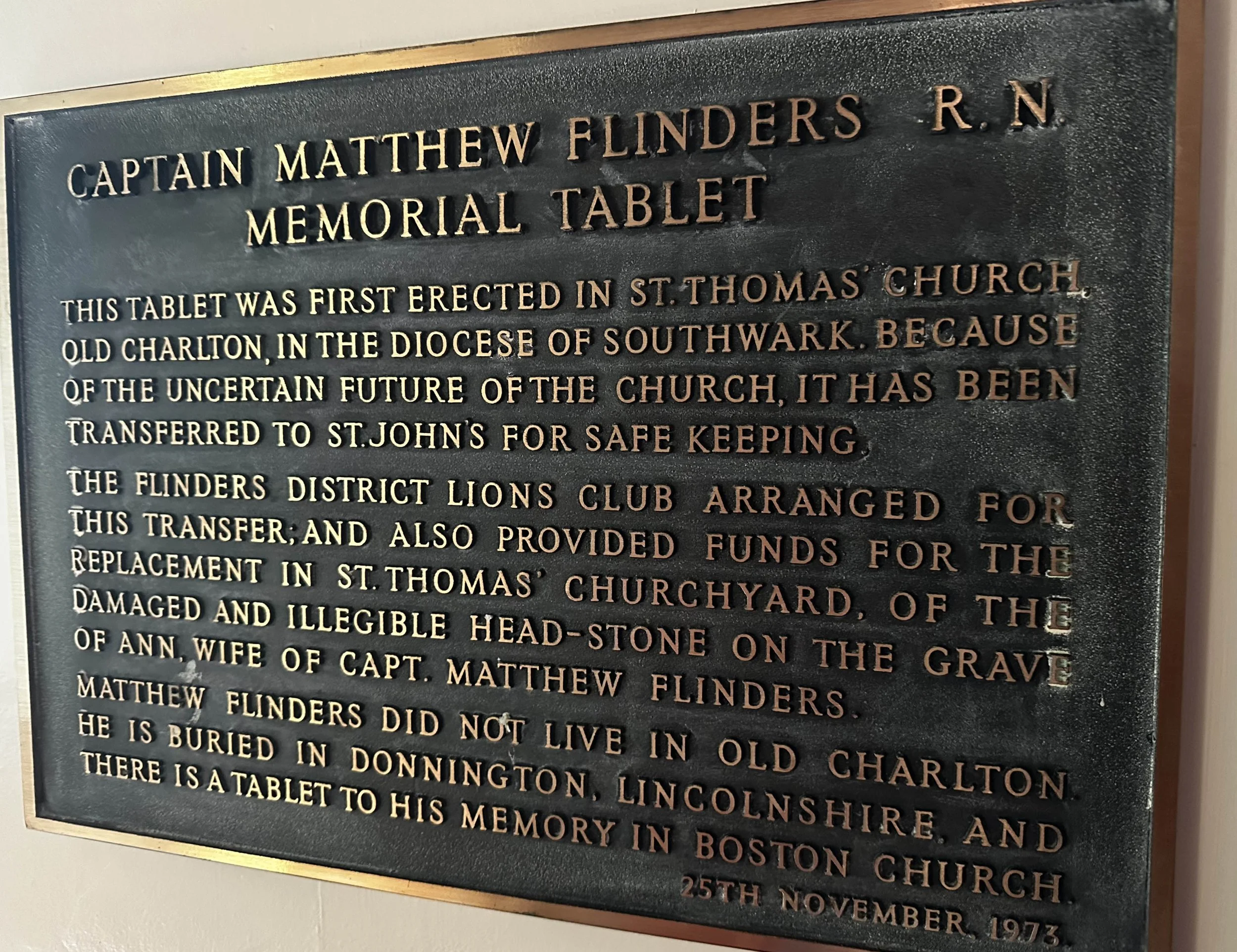

An adjunct: Remember Anne, Flinder’s widow paying for a Memorial Tablet? Its future became uncertain 54 years ago when St Thomas Church in London became a target for redevelopment. So, in 1973, the Flinders Lions Club saved the day. It funded a project that relocated that Memorial Tablet to St John’s Church in Flinders. The church is open most days, so call in and see the real deal. Here it is:

Another little adjunct: I mentioned that the British Admiralty refused a pension for Flinder’s family. That said, 40 years later [in 1853], the Colonial Governments of NSW & VIC voted to grant a lifetime pension to the Flinders family. It was too late for his wife Anne [who died the year before], but his daughter, Anna, set aside the annuity to educate her son. He became Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, widely considered the father of scientific archeology & Egyptology.

And a particular adjunct for you, Mark, as a boat tragic. Do you know the shameful end of ‘HMS Investigator’? When she limped into Port Jackson, having made the first circumnavigation of Australia, she was deemed unrepairable.

North West Side of the Gulf of Carpentaria by M. Flinders Commr. of H.M.S. Investigator 1803

That’s when Flinders set off for England to get another boat. But ‘Investigator’ eventually got patched up in Sydney enough to sail back to England, renamed ‘Xenophon,’ then sold to the Merchant Service. Sixty years after entering Port Phillip Bay [under Flinders in 1802], she returned with cargo for the Victorian Gold Rush. After 77 years of service, she was finally sold in Williamstown. Ironically, the ship that put Australia on the map [literally] finished up a coal hulk in Melbourne. In 1872, her register closed with the comment “broken up.” It was a dreadful end to arguably Australia’s most historically significant ship.

Russell Kenery