Freddie Mercury & The Lateen Rig

Words and contemporary Images by Mark Chew

Stonetown, Zanzibar

As I pushed through the narrow lanes of Stonetown, smelling the dried fish, cloves and cardamon, I stumbled across the “Freddie Mercury Museum”. Incongruous on many levels. I had discovered a bit of history not mentioned in that awful biopic “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

Mercury was born in Zanzibar's Government Hospital on 5th September 1946. He didn’t often speak publicly about his upbringing, but that has not stopped a lucrative tourist trade growing around him in the archipelago.

Freddie as a six year old in Zanzibar

Today, Queen fans can take tours of his childhood haunts - including his home, his family's place of worship and the court where his father worked. There is also along with the museum a Freddie Mercury restaurant and gift shop.

More problematic for many Zanzibaris is Mercury's bisexuality. Islam is the predominant religion on the archipelago and gay sex was made illegal in 2004.

There was outrage when it was rumoured gay tourists were making their way to the island for a beach party to mark Mercury's 60th birthday in 2006. But now it’s a major drawcard. Another case of Mammon trumping principle, in the search of the tourist dollar.

But Freddie Mercury is not why I came to Zanzibar. Early childhood memories of holidays at Lamu on the Kenyan coast are filled with images of powerful Dhows plying their trade up the East African coast. Our family always had a simple carved wooden toy dhow made out of driftwood, sail intact, hanging on the wall in the children’s bedroom. I had come to Zanzibar to refresh my childhood memory and to understand a little about these craft that had played a formative part in my appreciation of the vernacular of wooden boats.

For many centuries, dhows have sailed on the Indian Ocean. Despite their historical attachment to Arab traders, dhows were originally an Indian boat because much of the wood for their construction came from the forests of the sub-continent. Building dhows has always been considered an art and it has been passed down from father to son, preserving an age old design aesthetic. Even nowadays, there seems to be no need for written documentation such as plans or offsets in constructing a new Dhow. The plan comes directly from the shipwrights head, as the timber is sawn and hewn into established shapes (click to enlarge)

The dhow fleet was intrinsic to old Zanzibar when the Omani Sultans ruled and controlled the east African shores. When Sultan Said bin Sultan of Oman and Muscat moved his capital to Zanzibar in 1840, he travelled with his fleet of dhows to take possession. His family would rule Zanzibar till 1963 and the revolution that ousted the newly independent Zanzibar. Sultan Jamshid escaped while many other Arab Zanzibaris did not. Survivors tell of how many Arab people were forced to embark on overloaded and under provisioned dhows and sent to sea. The revolutionaries wanted them to go back to Arabia. Some of those dhows did not survive the trip.

The Arab dhow captains were superb seamen. In 1939, Australian adventurer, Alan Villiers, travelled on a dhow from Aden to Zanzibar and back. In his book, ‘Sons of Sinbad’ he recounts how he found a nakhoda or captain of a boum dhow and arranged his passage south with the north-east monsoon on a boat called The TRIUMPH OF RIGHTEOUSNESS. He tells of the journey and it is a window into the past. With western eyes he found the filth that accumulated on the overcrowded main deck difficult to stomach but recognised that these sailors were tough men:

‘the constantly cramped quarters, the crowds, the wretched food, the exposure to the elements, the daylong burning sun, the nightlong heavy dews, if they continued to be disadvantages, were far offset by the interest of being there….’

Nowadays the bigger Dhows in Zanzibar Harbour and the Port of Mkokotoni to the north, ply their trade with the Tanzanian mainland about 40 nm away, either to Dar Es Salam or the Port of Tanga, near the Kenyan boarder. The smaller Dhows, the ones that I managed to track down are mostly used for coastal trading amongst the small Islands off the west coast of Zanzibar and for local fishing.

On my first morning in Stonetown, I hired an old moped for a few days hoping it might give me access to some of the smaller harbours and anchorages on the Island, away from the tourist resorts, where I might be able to find a traditional boat builder willing to talk and show me his work. (And yes I’m afraid it is always a “he”)

I studied google maps (especially in Satellite mode) and asked myself where I would choose to build a boat given the topography and prevailing winds.

These sort of logical choices are the same the world over - and sure enough on the first morning I struck gold, coming across Ali, a proud, patient and genial shipwright with limited English, but like boat builders the world over, he didn’t mind a chat. He had three smaller Dhow hulls under construction and this is what I managed to find out. (click to enlarge)

Dhows are constructed much like the wooden boats we know in Australia with their European heritage. Somehow I find this reassuring. Its obviously an effective way to do things! A keel is laid, a stem is attached and planks are bent around frames. Interestingly the planks are softened by heating them over open flames rather than steaming them. The frames are at first sight remarkably crude being chosen for their grown form, and then sawn and plained into the required shape. There are no power tools used, not out of any purist attitudes but because they are unavailable. Drilling is done using a bow like device drawn over a hand held bit. (see pic 2 above) The keel and stem are made of teak, the frames are mangrove and the planks are mahogany. The planks traditionally were attached with wooden dowels, but nowadays iron nails seem to have taken over. Multiple heavy stringers run the length of the boat. Caulking is carried out almost identically to “western” methods, using cotton soaked in coconut oil. (see pics 4&5 above)

Once complete and roughly faired using a primitive plane, the hulls are rubbed down with a stinking, putrid paste, made of boiled sharks intestines. This seems to be an early equivalent of Everdure! Ali swears that a seasonal coating will preserve the mahogany and keep the teredo worms at bay, a problem that is obviously pressing having examined a few of the older vessels.

Boiled Shark Intestines

Teredo worm eaten plans

Applying the potion

The hull shape of a Dhow is not immediately attractive in the way that the lines of a western classic yacht are. Much of this is dictated by ease of manufacture rather than efficacy. The sheer is not always smooth and the hull form can be jarring. Or perhaps thats more about the sensibilities of an observer spoilt by the sophisticated building methods and tools of western shipwrights. Designed mainly as cargo vessels, the goods act as ballast and if they are required to sail without cargo they will load up with sand bags to keep the boat stable.

Ali built the boat in the picture below on spec in two months with the help of three other people. “INAUZWA” written on the transom, means “for sale” in Swahili…asking price 9.5 million Tanzanian shillings or close to $6000AUD.

Having spent a couple of hours talking with Ali, I made my way further north up the western coast until I came across some local trading Dhows heading out on the first hint of an afternoon sea breeze. As quickly as possible I negotiated a ride on a local dingy with a diesel outboard and headed out into the channel to take some photographs. (click to enlarge)

It’s really the Lateen or Settee rig of the Dhow that gives it its recognisable personality. It’s this distinctive sail that makes these craft so special. It must have been one of the first rig designs that could genuinely sail to windward.

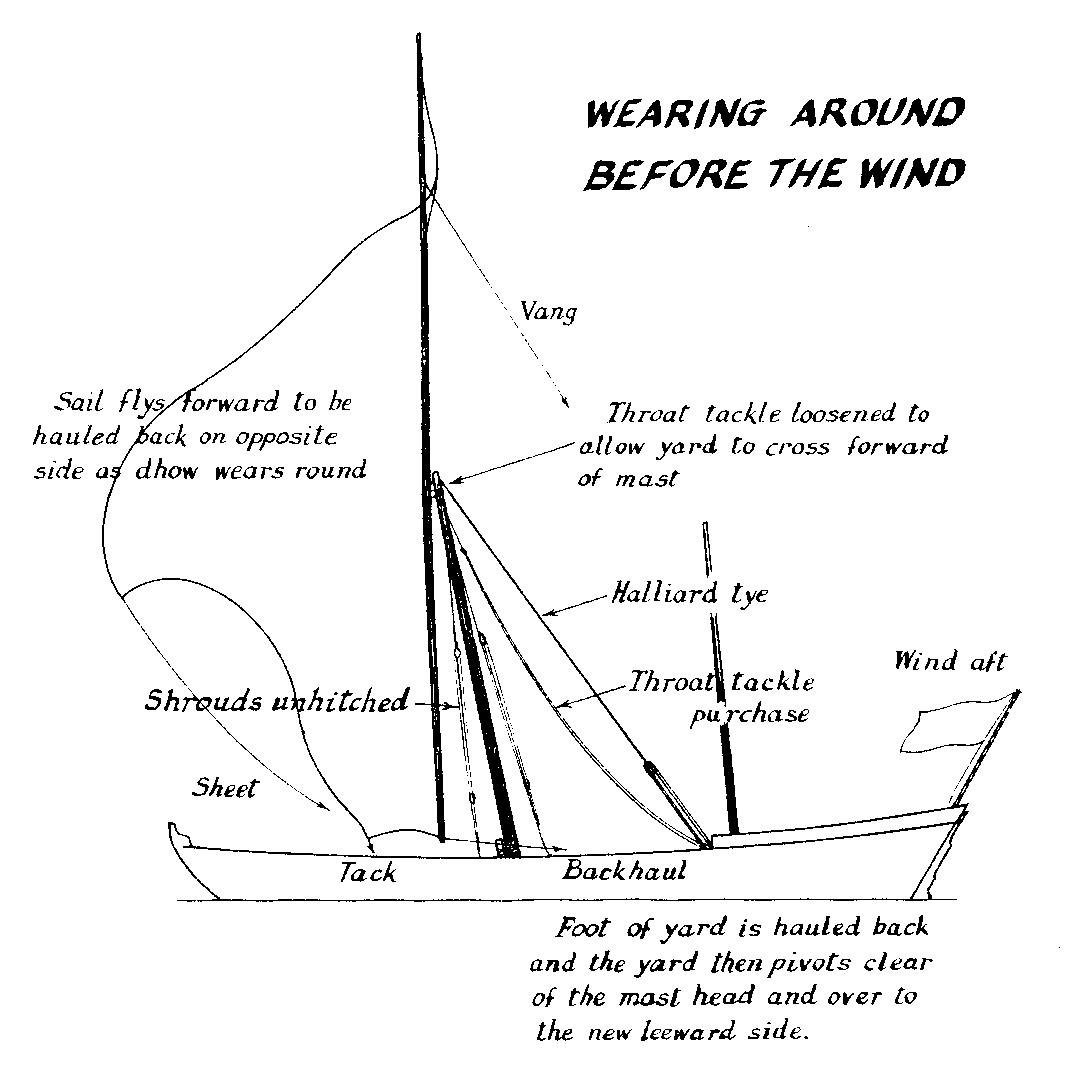

The forward leaning mast and huge settee spar are iconic. The lateen sails are not completely triangular. The forward angle is cut off to form a leading edge. This luff allows a much greater area of sail to be hoisted than a completely triangular design would do. The lateen has an enormous advantage over multiple square-rigged sails since it allows the dhow to sail well into the wind. The long strips of the cloth are sewn together, parallel to luff and leech. The upper edge of the lateen sail is tied up to a leaning yard, which is in turn attached high on the mast by a strong rope called a parrel. The yard is very long in comparison with the mast, and is often made of more than one piece.

Changing board, or wearing a Dhow with its huge and heavy settee spar, is apparently not as difficult as might be assumed, provided that work is co-ordinated. Clifford W. Hawkins, in his book “An Illustrated History of the Dhow and its World”, describes observing the process from aboard a small boat:

"As we closed in on the sambuk (a common two-masted dhow of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, South Arabia, and East Africa) I could see that some action was about to take place. The crew, rising off their haunches, casually sauntered to working positions; one right up int he bows at the mains'l tack, four at the shrouds, two to the yard's backhaul and a small group ready to handle the main sheet. These were the action stations for wearing ship, the preliminary operation for sailing on the opposite tack. When the critical moment arrived the helmsman threw over the wheel to bring the wind aft and the big mains'l was allowed to fly forward with the release of its sheet. Every member of the crew now came into action to carry the operation through. The two shrouds that had been taught to windward were eased off and the other pair set up on what was already becoming the new windward side. The yard, which had been freed from the masthead by letting loose the parrel, was at the same time hauled momentarily by the foot, so allowing it to pass over to the forthcoming leeward side. The flying sail was then hauled back and sheeted home on the opposite side to where it had been. it filled out and the sambuk was away on the new tack.

"Surprisingly the operation of wearing ship was not a long or very difficult procedure. The dhow turned unhesitatingly on its heel and was away on the new board with the loss of very little ground. It is possible for a dhow to go about, head to wind, but in doing so it would be in a somewhat similar position to a square-rigged sailing vessel caught aback with the great settee sail afoul of the mast and rigging. In an emergency a dhow could sail, after a fashion, like this.”

I had hoped to get a ride on a big trading Dhow. But this was a formidable task. My Swahili is basic at best and having been learnt in the urban areas of Kenya, it seems to bear little resemblance to the coastal Arab version it evolved from. In addition to this, the traders are naturally suspicious of outsiders which, given their history is understandable. But if I ever get back here, I think with time and persistence and a bundle of Tanzanian shillings, I’m sure a sail powered trip on a working Dhow across the Zanzibar Channel would be entirely possible. Now there’s a challenge!