Head and Shoulders Above Their Contemporaries

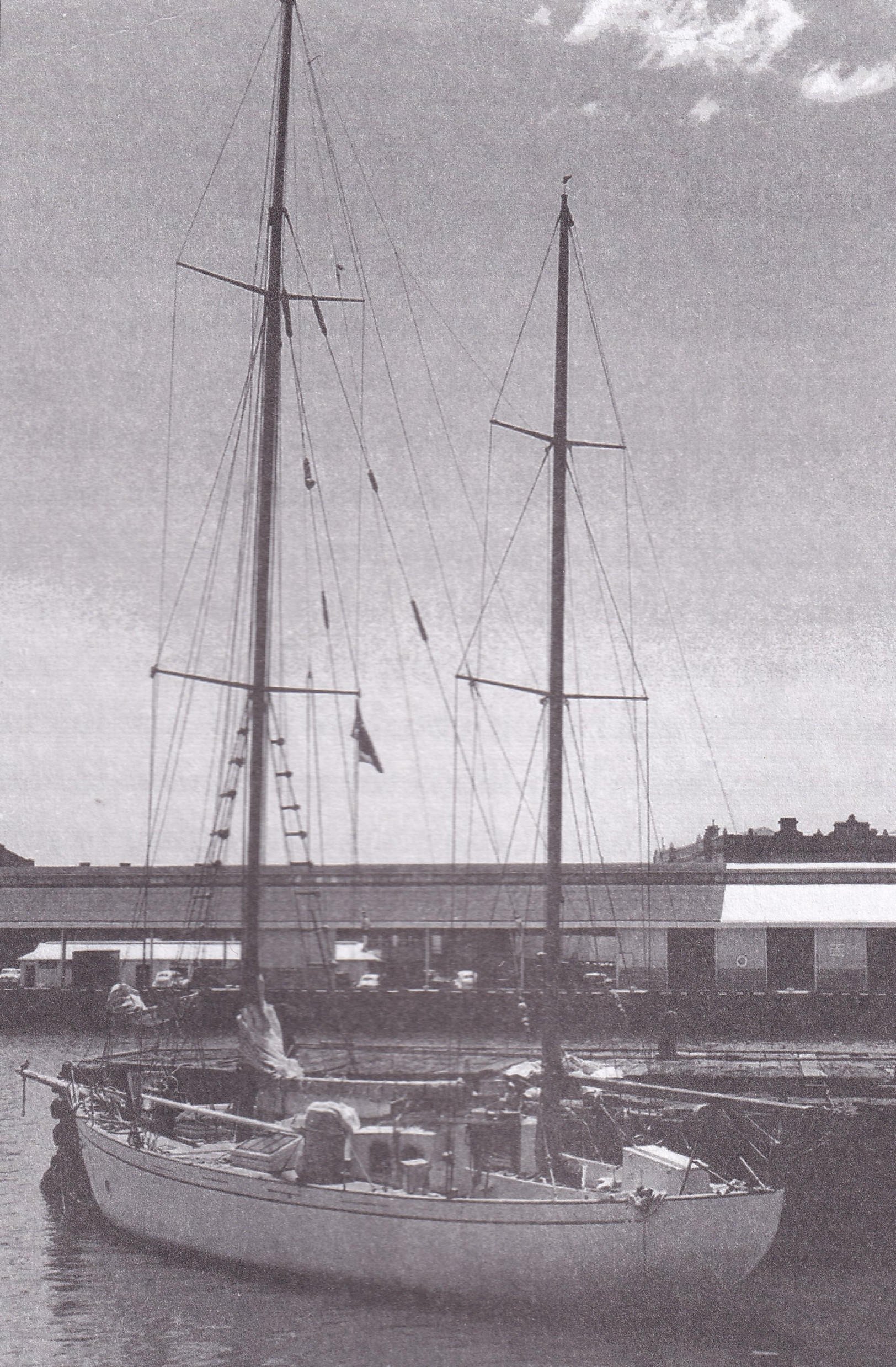

Tzu Hang moored in the Yarra River in Melbourne

By Graham Cox

Among the rushing, excited crowds in downtown Melbourne during the 1956 Summer Olympics, the presence of a 46’ ketch on the Yarra River, even though it was flying the Red Ensign, would have scarcely been noticed, especially since it was dwarfed by the Royal Yacht, Britannia, moored opposite, which drew daily crowds.

Those who did make enquiries would have found that it was called Tzu Hang, had been built in Hong Kong from teak, with bronze and copper fastenings, and shipped to England in 1939. It was purchased in 1951 by Beryl and Miles Smeeton, an English couple who had settled on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia, Canada, and had been sailed out there via the Panama Canal, before crossing the Pacific Ocean in 1956. The ketch was now bound for England via Cape Horn.

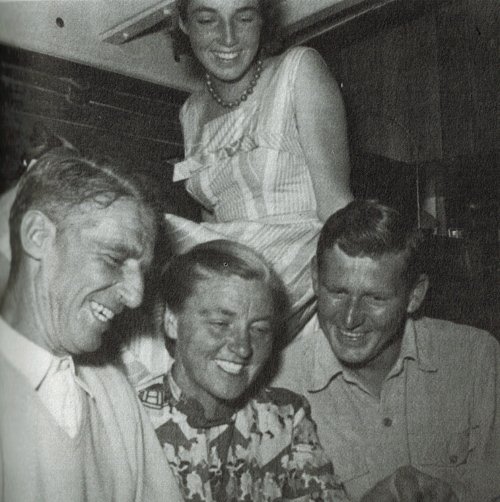

Clio, left, Beryl and Miles, with Poopah, Clio's dog, and Pwe, shortly after arriving In Victoria, BC from England, June 1952.

Beryl and Miles were unknown then, as was their young crewman, John Guzzwell, but all three of them would go on to become household names among anyone with an interest in voyaging under sail. On 14 February 1957, Tzu Hang pitchpoled in the Southern Ocean on their way to Cape Horn as recounted in the book Miles wrote, Once is Enough, first published in 1959, and still in print, a story that captivated the world.

John Guzzwell also published an account of that event, in his evergreen book, Trekka round the World, but his story, and that of his 20’ 6” yawl, will have to wait for another time. The story of Beryl and Miles is more than enough to fill an entire biography, let alone a short article. They were extraordinary people.

From left to right, Miles, Beryl, and John Guzzwell, with 14-year-old Clio behind, during their Pacific crossing to Melbourne in 1956.

If ever a couple were made for each other, it was these two. They were equally fearless, courageous and tough. Miles, who retired from the British Indian Army with the rank of brigadier in 1947, was famous for standing up in his armoured vehicle during battle in WW2, directing the action, heedless of enemy fire, and was revered by his troops, while Beryl was known for riding a horse from Ecuador to Tierra del Fuego, and later walking from Shanghai to Rangoon in the 1930s, both journeys considered insane for an unaccompanied woman, or possibly anyone.

Beryl, who was also in the army when they met, was married to someone else, but they recognised each other immediately. Before long, they were scaling mountains and trekking across deserts together, and married in 1938. I get the impression that, in many ways, Beryl was the driving force behind their partnership.

It was she who declared that she’d like to sail Tzu Hang back to England via Cape Horn, and who talked a reluctant Miles into it. In Because the Horn is There, the account of Tzu Hang’s third, and finally successful attempt to round Cape Horn, Miles wrote that he would have been quite content to leave things as they stood (two failed attempts), but that Beryl never liked giving up on things, and that the failure had rankled her for years.

He also mentioned a military report about his conduct in the army, which read, ‘This officer has an ability to get himself out of situations he never should have gotten into in the first place.’ Miles claimed the report should have read, ‘situations his wife got him into…’

In a new edition of Trekka Round the World that John Guzzwell produced in 1999, he reinstated some passages that were edited out of the original book by his first publisher, Adlard Coles, including a hilarious account of picking up a mooring with Tzu Hang at the Akarana Yacht Club in Auckland, in full view of the commodore and other club members. The episode shows something of Beryl’s steely character.

Unknown to the crew, the engine’s gearshift lever had disengaged from the transmission, with the consequence that when Beryl put the gear lever in reverse and revved the engine to stop the yacht, it charged ahead at 7 knots, ramming Miles in the dinghy and capsizing it. He was just able to leap out of the dinghy as it went under, and climb up the bobstay, while John hastily thew over the main anchor.

Miles had been yelling at Beryl to put the motor in reverse, which apparently upset her, since she knew she had followed his instructions. ‘Did I get the bastard?’ she asked John coldly, adding, “Oh, good!’ when she saw the upturned dinghy disappearing astern. Luckily, the anchor dug in, Miles climbed up the bobstay and cut the engine, and the boat, which had been steaming around in circles, came to a halt. Beryl had gone below and was knitting on the saloon settee. John noted that he and Miles knew when to shut up.

I remember reading Peter Pye’s description of meeting them by chance at his local boatyard in Essex, UK, one cold, autumn morning. Peter, who’d recently returned from a voyage to the Caribbean with his wife, Anne, aboard their gaff-rigged cutter, Moonraker, said that there was a keen north wind blowing down from the Arctic, and the smell of snow was in the air, but Miles and Beryl wore no overcoats or hats, and the shirt Miles was wearing had a couple of buttons undone, with the hairs on his chest peeping out. They were laughing gaily at something, faces full of delight at being alive.

The Smeetons said they were looking for a yacht, despite having never sailed before, in which they proposed to sail back to Canada. It sounded foolish, and plenty of other dreamers in those post-war years never got beyond England’s shores, but not many people are as capable as the Smeetons.

When introduced to Peter Pye, Miles mentioned, perhaps with a lack of tact, that he’d met a friend of theirs, who told him, to paraphrase slightly, ‘If that man could cross the Atlantic in a boat like his, I am sure you can.’

The Smeetons found Tzu Hang shortly after, and the two couples became close friends, so much so that the Pyes sailed Moonraker out to British Columbia, via Panama and Tahiti, to visit the Smeetons the following year, as recounted in Peter Pye’s book, The Sea is for Sailing.

I remember an amusing incident, recounted by Miles in The Sea was our Village, when Peter and Anne sailed Moonraker past Tzu Hang for the first time, and Miles called out, ‘What do you think of her?’ To which Peter replied, ‘Too much freeboard,’ perhaps a fine retort to Miles’ earlier comment. Miles later said that ideas about appropriate freeboard have changed since those days, and he considered Tzu Hang’s freeboard to be just about perfect.

Moonraker departing England to visit the Smeetons in British Columbia, June 1952. Note the low freeboard!

Moonraker, as Miles pointed out to a crestfallen Beryl, had hardly any freeboard. It was just an ancient fishing boat, with old cogwheels and cannonballs (I kid you not) wedged in the bilges for internal ballast. Anne Pye famously said that they sailed with one hand in God’s pocket (and the other, perhaps, on the bilge pump). But the story of Peter and Anne Pye will also have to wait for another day.

Another vignette recounted by Peter Pye was of the misty day when he and Miles stood together on the deck of Tzu Hang, and Miles said, looking out beyond the bowsprit, over the low banks of the river that seemed to disappear into space, ‘The world would be intolerable if adventure were not just around the corner.’

The Smeetons sailed Tzu Hang out to British Columbia via Panama without incident over the following year, a remarkable feat for people who had never set foot on a boat before. The plan was conceived as a way to get their funds out of Britain, which had a monetary freeze in place, but by the time they got home, they’d fallen in love with ocean cruising as a way of life.

A few years later, they sold the farm on Salt Spring Island and set sail for the Melbourne Olympics. They met John Guzzwell and Trekka in Sausalito, California, in July 1955, after his inaugural passage south from Victoria, BC, and the two boats rendezvoused in various ports across the Pacific to New Zealand. Guzzwell left Trekka in storage there and joined Tzu Hang for the passage to Melbourne via Sydney, then on to the Southern Ocean.

In Trekka Round the World, John Guzzwell gives an amusing account of building a new mainmast for Tzu Hang on the island of Maui in Hawaii. A Hawaiian of short stature approached John in the workshop, asking how tall he was, and where he came from. John replied that he was six feet tall, was born in England, but lived in Canada now. Then Raith Sykes, a 6’ 3” Canadian who was crewing on Tzu Hang, and also originally from England, arrived in the workshop. Finally, 6’ 6” Miles turned up, with 14-year-old Clio, who was already 6’ tall, and the Hawaiian was convinced that English-born Canadians were a race of giants.

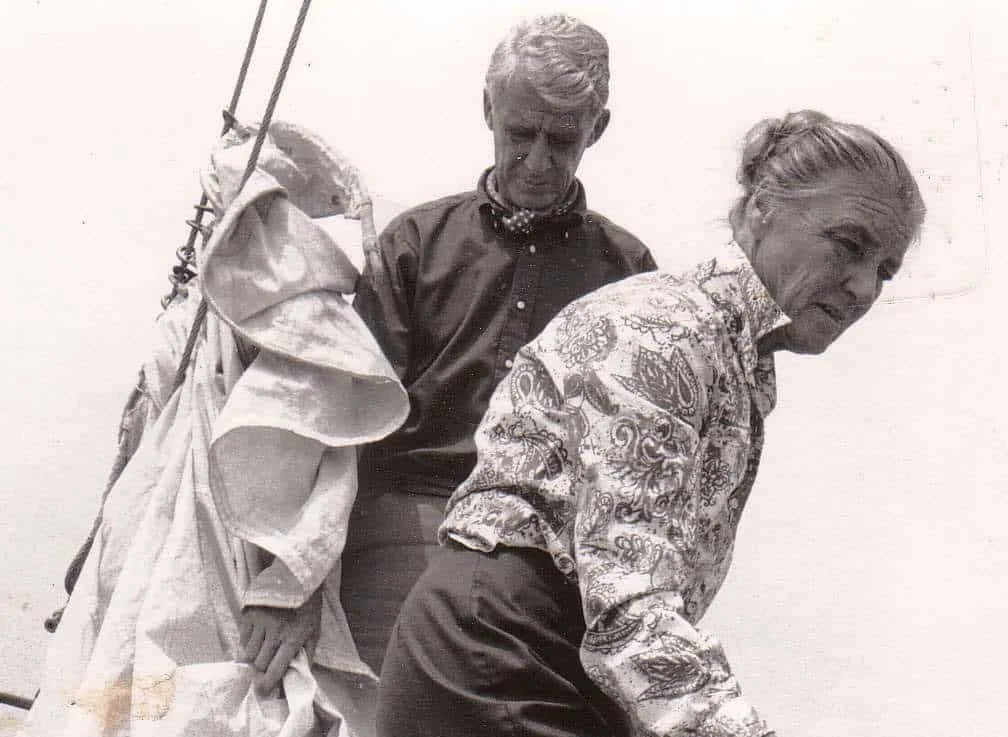

They wouldn’t let Beryl visit, as she was only 5’ 7”. To add to Miles’ stature, he stood ramrod straight, possibly the consequence of a lifetime of military service, and his posture, along with his height and reserved demeanour, gave him a commanding presence that was often commented upon.

This reserved demeanour is very noticeable in Miles Smeeton’s books, all except the last one, The Sea was our Village, published in 1973, which happens to be my favourite. Recounting their first voyage, from England to Vancouver, BC, in 1951-2, but written a few years after they made their final passage aboard Tzu Hang, the writing is very relaxed and playful, resulting in a vibrant story. I am not sure what the Smeetons thought of the ‘hippie movement’ in the 1960s (not much, I suspect), but something of the social mores of that era seems to have infused this work, and allowed Miles to relax his somewhat rigid public persona.

For the next twenty years, the Smeetons roamed the oceans of the world, along with their faithful Siamese cat, Pwe, who became almost as famous as them, and Miles wrote several books about their voyages. What they are best known for, though, is the book, Once is Enough, recounting their first two attempts to sail around Cape Horn, and Tzu Hang’s subsequent travails.

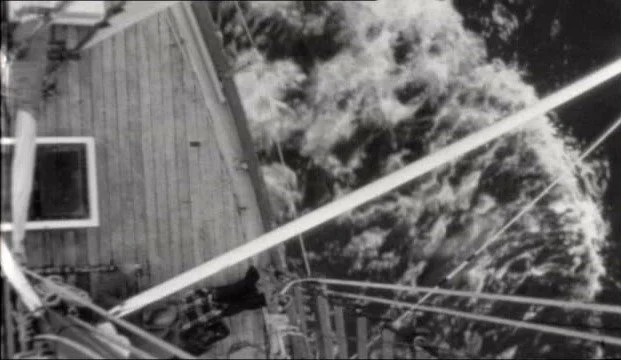

Video of surviving segment of John Guzzwell film taken aboard Tzu Hang, including footage taken just before the pitchpole.

On their first attempt, running down the westerlies from Melbourne with John Guzzwell aboard, they pitchpoled in the approaches to Cape Horn, losing both masts, the coachroof and the rudder. For a while, it looked like the ship would founder, but somehow Tzu Hang rose over the following sea, despite being waist-deep full of water, and with a gaping hole in the deck where the coachroof had been. Realising they had a chance, they bailed furiously until most of the water was out, then began emergency repairs.

Ultimately, they all survived, even Pwe, who was in poor shape for many days after the disaster. They nailed sails over the gaping holes in the deck, built a jury mast and later a steering oar, and brought themselves to landfall in northern Chile, near Coronel, some 34 days after the storm. They were lucky that the ship did not founder, and their survival skills were par to none, but their self-rescue was what people did in those more self-reliant days, when offshore sailors did not have EPIRBS or satellite phones.

Tzu Hang after the pitchpole, sans bowsprit. Photo Clio Smeeton

Undaunted, the Smeetons set sail for Cape Horn again the following summer, without John Guzzwell this time, who had returned to Trekka in New Zealand. This time, they were rolled over while lying ahull in a gale, losing both masts, but did not suffer as much damage as the first time. Capsizing a vessel, while dangerous, is far less violent than a pitchpole. Limping back to Chile, they chose to ship Tzu Hang back to England for a proper rebuild. As Clio said to her mother, once was enough, but twice was definitely too much!

From England, after completing repairs, they set sail to the east, through the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, East Africa, Durban - South Africa, the Seychelles, SE Asia, Japan, the Aleutian Islands, Canada, Panama, and back to England, completing a decade-long eastabout circumnavigation without drama, recounted in several books. Finally, in 1968, they set their sights on one last attempt at Cape Horn, with Bob Nance, an Australian, as crew.

Bob’s brother, Bill, incidentally, had recently completed one of the most daring circumnavigations of all time, eastabout via the Southern Capes, including Cape Horn, in the 25’ Vertue-class yacht, Cardinal Vertue, known earlier for its participation in the inaugural Singlehanded Transatlantic Race in 1960, under the command of Dr David Lewis. Bob had himself recently rounded Cape Horn on the 31’ Australian-flagged, Carmen-class sloop, Carronade, built in Sydney by it skipper, the equally young Andy Wall.

This time they made a successful voyage back to British Columbia via Cape Horn, Chile and Hawaii, after which Miles and Beryl sold Tzu Hang to Bob and retired to a life ashore, prompted possibly by a life-threatening medical emergency Beryl suffered in Honolulu. After retiring from the sea, they founded an endangered-species animal sanctuary with their daughter, Clio, in Alberta, Canada. Beryl passed away in 1979, and Miles died in 1988, but not before making one last ocean passage, this time as crew, aboard John Guzzwell’s 45’ Laurent Giles-designed cutter, Treasure, sailing from Victoria, BC, to Honolulu, Hawaii.

Every generation produces exceptional sailors and adventurers, though with the advent of satellite communications and navigation systems, it is arguable that we will never again know people with the independence and resilience of the Smeetons. Even in their era, when going to sea meant casting off from the land and not being heard of again for weeks or months, until making your next landfall, they stood head and shoulders above most of their contemporaries.

Early books by Beryl Smeeton:

The Stars my Blanket.

Winter Shoes in Springtime.

Sailing books by Miles Smeeton:

Once is Enough.

Sunrise to Windward.

The Misty Isles.

Because the Horn is There.

The Sea was our Village.

Other books by Miles Smeeton:

A Taste of the Hills.

A Change of Jungle.

Completely Foxed.

Moose Magic.

Alligator Tales: and Crocodiles Too.

A note about the author: Graham Cox is a singlehanded sailor, historian of small-boat voyaging, and author of the just-released, Last Days of the Slocum Era, Volume One and Volume Two. The print versions of this two-part sailing memoir / selective history of cruising under sail since the mid-1960s, will be available from Amazon.com or Amazon.com.uk, in late May, 2024, or can be ordered from your local bookshop or library. The ebook versions will be available from the above sources as well as from Kobo, or Barnes and Noble. Graham is also the author of the Junk Rig Hall of Fame, and currently lives aboard his Cavalier 32, Mehitabel, in Kawana Waters Marina, Mooloolaba, in Queensland.