Hokule'a- Traditional Sail, Cultural Renaissance, Alternative Paradigms

By Duncan Blair from the “Traditional Sail” website

Voyages by HOKULE’A and several other sailing vessels appear to be bringing about a “quiet renaissance” of traditional sail. The flowering of this renaissance is of great interest to me, most especially given the circumstances of the post-Covid era.

The continuing voyages of HOKULE’A (46 years have passed since a maiden voyage to Tahiti), and intelligent and creative use by the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) have demonstrated “the power of the boat” as a platform for education, advocacy and cultural continuity.

The efforts of PVS are matched, in slightly different ways, by the efforts of Chasse Maree (see TS The Relevance of Traditional Sail, Jan.14, 2022), the Maine Windjammers Association and other organizations focused on traditional sail.

There has also been the very interesting appearance of relatively small sail-powered ships carrying wine, rum, coffee, cacao and passengers across the Atlantic, to and from Central America and the Caribbean. Added to this is the general cargo service of SV KWAI in the Marshall Islands (see TS SV KWAI Feb. 15, 2022), and the lugger GREYHOUND, built in 2012, which regularly carries passengers, wine and rum between Cornwall and Brittany.

So, Traditional Sail, Cultural Renaissance and Alternative Paradigms are all out there after all—Who Knew?

In the near future I plan to “think out loud” once again about the possibility and feasibility of small (30–50 feet long) sailing vessels; not yet built, being used as platforms for teaching middle school kids, and enabling learning in the post-Covid landscape of home schooling cooperatives, Charter schools and renewed focus on quality education. This approach would include learning STEM concepts while sailing in local waters, studying ecology and environmental science while at anchor in an estuary, and learning local maritime history on a rainy or a wind-less day while tied up at the dock, under a canvas awning.

THEN the students return with their parents for an Open House where the kids can share all the amazing things they have learned with their parents—while on the boat itself.

A wise man recently said that with all the problems of the world, if you “solve for education”, the remaining problems diminish.

Please think about this as you read about how HOKULE’A, the craft’s builders, sponsors and crew demonstrated, and continue to demonstrate “the power of the boat.”

HOKULE’A

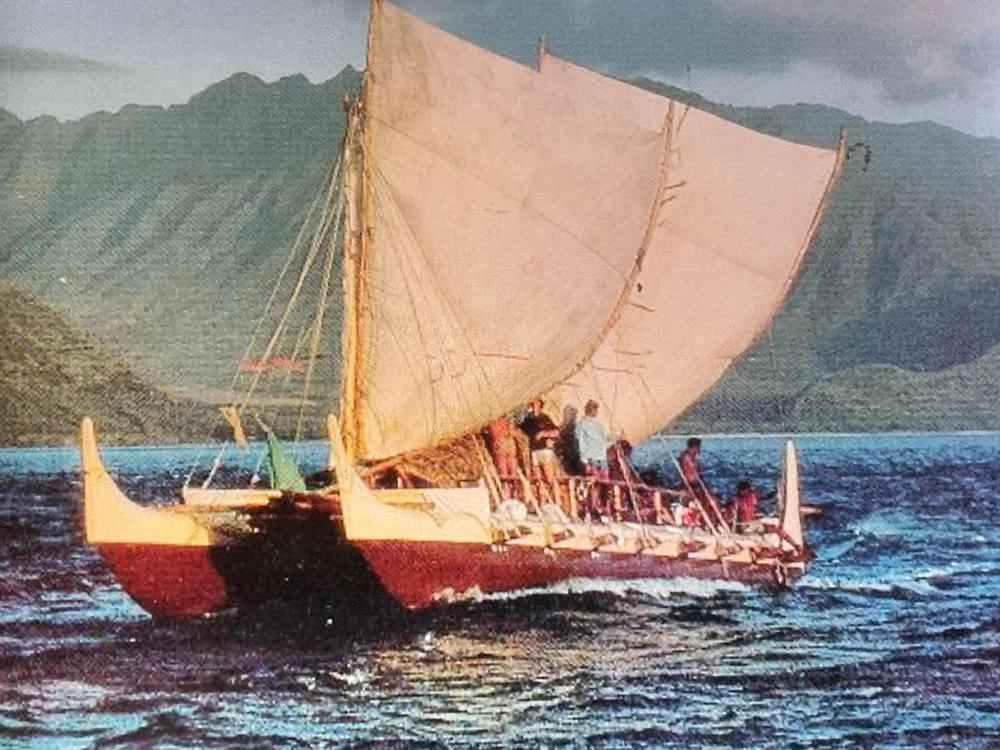

HOKULE’A, Star of Gladness, is a double-hulled Polynesian sailing canoe, having two masts and “crab claw” sails. Built using fiberglass and plywood by the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1973 - 61 ft 5 inches long, 15 ft 6 in-beam and displaces 8 tons. The boat has 540 sq. ft of sail and is capable of 4 to 6 knots. There is no auxiliary motor and is steered with a long paddle. The crew is 12–16 people. The guiding principle in design and construction was to be “performance accurate.”

A first voyage in 1976 represented a bold attempt at what is known as “experimental archaeology,” testing aspects of material culture, in this case an arcane boat type, in order to understand their function and practicality.

It is important to note that no physical remains of large double-hulled sailing canoes have ever been found, excavated or measured; no Gokstad ship or Vassa equivalent. The only record of these canoes is a few drawings made by English gentlemen volunteers accompanying Capt. James Cook, RN, on his several voyages to Hawaii in the 18th century— “experimental” indeed.

Another stated goal of the 1976 voyage was to test Polynesian-style navigational techniques: that is, to cross 2400 nautical miles of ocean without compass, sextant, quarter staff, charts or a time piece—and to make landfall on Tahiti. HOKULE’A left Maui, Hawaii and successfully sailed to Tahiti in about 5 weeks. Navigator, Mau Pialog, was Polynesian, although not Hawaiian. He was one of the last of his kind. He had a lifelong connection to the sea and had been taught the mysteries of Polynesian ocean “way finding” by his grandfather.

“Way finding” is the polar opposite of the Western approach to navigation, being based not only on observation of sun, moon and stars but also observing birds, wave patterns caused by swells refracting off unseen islands; cloud formations, sea wrack and, to the degree that I understand it, on a completely different conceptual framework from what we have i.e., a different paradigm.

In addition to achieving the goals of a successful voyage and successful way finding, there was a third, possibly unforeseen result.

By the 1970s Polynesia in general and Hawaii in particular appeared to have lapsed into a state of serious cultural malaise and disfunction. Centuries of isolation from the rest of the world had been interrupted by the coming of European and American sailors and whalers, missionaries, venereal disease, soldiers and more sailors on military bases, sugar and pineapple plantations, immigrant laborers, American tourists, Japanese investors and even more tourists. The Hawaiians had lost much of their land, their language was in decline and their traditions appeared to have been trivialized down to tourist luaus and “hula shows.”

HOKULE’A dramatically changed all that. Greeted in Tahiti by thousands of ecstatic people—dressed in their finest ceremonial outfits—with blowing conch shells, singing and drumming. They came from all over to see this boat and its crew who had, by successful voyaging and navigating, completely disproved the prevailing “scientific” view that Polynesians could not purposefully and successfully make open ocean “voyages of discovery.” Hokule’a gave them back their pride, their power, their “mana”. Behold the power of the boat— a sailing boat of traditional design in the 20th century!

Subsequent voyages across Polynesia brought the same response; a vast outpouring of joy, pride and deep happiness—HOKULE’A lived up to the name “Star of Gladness”.

The PVS had made a risky attempt and were rewarded for it. But the boat, the sailing canoe, became a symbol and “lightening rod” of Polynesian identity, remaining so today, 45 years after the first voyage.

HOKULE’A has had some ups and downs over the past 45 years. In an early “shakedown” cruise the boat capsized in the Molokai Channel. One crew member (Eddie Aikau) went for help on his surf board and was never seen again. Mau Pialag was frustrated and angered by the spoiled brat attitude of some crew members and left the boat in Tahiti but later returned to help Nainoa Thompson, a PVS key member, to learn the “traditional ways of knowledge” approach to Polynesian navigation.

Since 1976 HOKULE’A has circumnavigated the planet and is now scheduled to make another voyage in 2022 accompanied by a “sister” canoe, HIKIANALIA—named for the star SPICA (in the constellation we know as Virgo.)

This voyage is planned to take 42 months and cover a distance of 41,000 miles. Imagine the planning, the crew changes, the challenges and the logistics. Imagine the opportunities! Nainoa Thompson, now head of PVS, has said of this voyage that “these canoes can help protect our extraordinary island that we call Earth!

A PVS press release says the voyage “will focus on the vital importance of oceans, Nature and indigenous knowledge.”

I know very little about the Polynesian Voyaging Society. I get the feeling that having survived for 45 years after a beginning best described as “quixotic” they are well organised and well funded. They also seem to be well-connected and are adept at communication, public relations and politics.

Why bring up politics? Because from the moment that HOKULE’A struck the spark that ignited Polynesian pride, from the moment she validated and vindicated the un-known, un-documented, un-scientific history of Polynesia she became political. Using her as an advocacy platform for ocean health, Nature and indigenous knowledge is politics writ large.

So maybe the rest of us who are not Polynesian but clearly and proudly have our own traditions of working sail should think about using our skills, our traditional “ways of knowing” and our boats in our home waters to advocate, to call attention to and to educate others concerning the state of our oceans.

Who better than us, who use and honor the oceans and who have at hand, like the Polynesians, the “power of the boat”—a universal icon and rallying point.

Epilogue—Information on HOKULE’A, Mau, PVS and Polynesia is abundant, both on-line and in academic literature. In my opinion the very best book that brings all the conjecture, research and actions together is Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, by Christina Thompson. In it Thompson also does a very good job explaining Polynesian cosmology and how “way finders” viewed and understood their oceanic world, Don’t miss it!