Hold on; it’s got us!

by Russell Kenery

Painting by Andy Murray

Ernest Shackleton has exalted status, and his ridiculous voyage to South Georgia marks the end of the Great Age of Exploration. Still, the success of that hellish small boat dash was because of the brilliant seamanship of a self-deprecating Kiwi.

Frank Worsley was an ocean-wise 43-year-old New Zealander when he skippered the ENDURANCE on Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

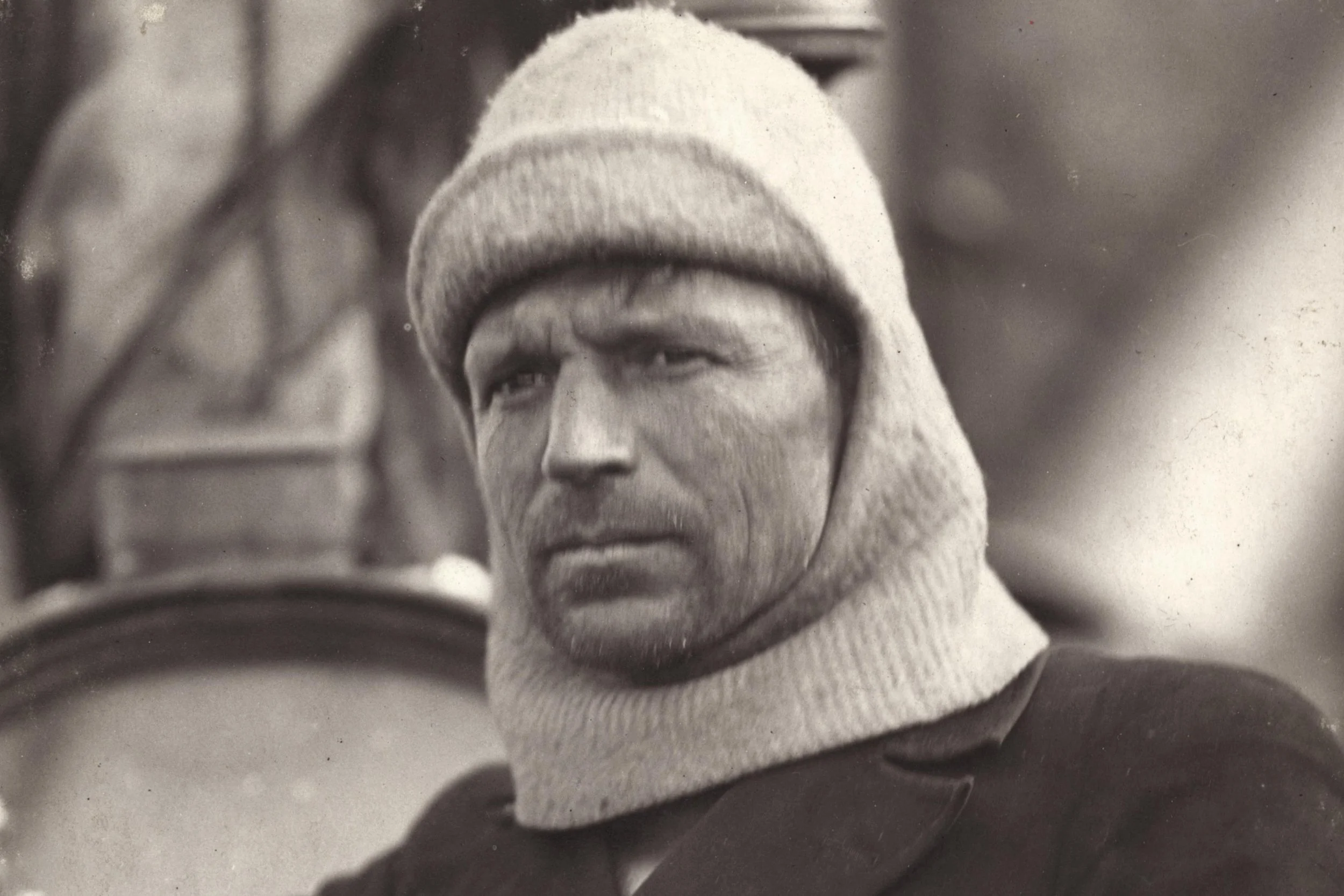

Frank Worsley, captain of the ENDURANCE on Shackleton’s 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

On 5 December, ENDURANCE departed South Georgia only to become trapped for ten months in pack-ice before breaking up. For the next five months, the 28 men of the expedition camped on the pack-ice, the ocean swell rolling underneath. When the ice began breaking under them, they took to ENDURANCE’s three lifeboats. They landed safely on tiny Elephant Island in the uninhabited South Shetland Islands six days later, but nobody knew they were there. Winter was looming, and Antarctica in 1915 was one place on Earth where you could expect no help. They were trapped and faced no chance of survival because rescue would never come.

Shackleton was determined to get home, and his plan was simple: he would sail out and get help to rescue the stranded men. Worsley wrote of Shackleton,

“Being a born leader; he put himself in the position of most danger, difficulty, and responsibility. I have seen him turn pale yet force himself into the post of greatest peril. That was his type of courage; he would do the job that he was most afraid of.”

Although the Falkland Islands were closest, they were upwind of the prevailing westerlies, so Shackleton decided to run 800NM northeast for the tiny island of South Georgia. In Worsley’s words,

“We knew it would be the hardest thing we had ever undertaken, for the Antarctic winter had set in, and we were about to cross one of the worst seas in the world.”

No other boat journey faced such appalling risks and clear-cut responsibility for life and death.

Along with Shackleton, the chosen boat party were all exceptionally tough sailors: Timothy McCarthy, “perhaps the most gifted natural sailor,” John Vincent, Harry McNish, and the fiercely loyal Tom Crean “who begged to go.” Crean was on his third Antarctic expedition, and in 1912 led the search party that found the bodies of Robert Falcon Scott and his companions. Crean had immense stamina and “a fund of wit and an even temper which nothing disturbed.” But their lives were to depend on Worsley’s navigation, and he took with him his sextant, chronometer, Nautical Almanac, and a chart of South Georgia that was a composite of running surveys by Cook [1775] and Bellinghausen [1819].

A section through the JAMES CAIRD, illustrating the ballast, cockpit arrangement, and sleeping quarters in the bows.

The strongest lifeboat was the 22ft James Caird, built to a chunky Norwegian ‘double-ender’ design, as ordered for ENDURANCE by Worsley. The carpenter raised her gunwales by 20 inches and improvised decking oversewn with canvas. A small cockpit was built-in aft and a steering yoke fitted on the rudder stock. The mast from one of the other lifeboats was fixed along the bilge to stiffen the hull, and, given she was keel-less, they loaded a ton of rocks to add stability. She carried a two-masted ketch rig with loose-footed lugsails, jib staysail, and four oars.

JAMES CAIRD was pushed out from Elephant Island on 24 April 1916.

From Elephant Island, Worsley headed north for two days to clear the sea ice that was beginning to form. She lay a course for the Drake Passage, the legendary stormy and most dangerous waters in the sub-polar region. Conditions on the boat were bitter, with air temperatures below freezing and frigid seas heaping up. The makeshift decking leaked, so with everything wet, hypothermia and frostbite were significant dangers.

Five days into the voyage, a glimpse of the sun enabled Worsley to fix a sight that confirmed they were on course. But from then on, navigation was what he termed

“a merry jest of guesswork.” Worsley later wrote, “Once, perhaps twice a week, the sun was a sudden wintery flicker through storm-torn clouds. Only if I was ready for it and quick smart, I caught it. The procedure was: I peered out from our burrow with the precious sextant cuddled under my chest to prevent seas falling on it. Sir Ernest stood by under the canvas with a chronometer, pencil, and book. I shouted, “Stand by!” and knelt on the thwart, two men holding me up on either side. I brought the sun down to where the horizon ought to be, and as the boat leaped frantically upward on the crest of a wave, I snapped a good guess at the altitude and yelled, “Stop!” Sir Ernest took the time, and I worked out the result.”

Worsley’s intuitive navigation was his guesstimates of speed and direction because he had so few sun sightings. He thought his dead-reckoning calculations were probably within 10NM, but he also knew it was a matter of life and death. If Worsley were wrong, JAMES CAIRD would sail beyond South Georgia into oblivion, and nobody would rescue those on Elephant Island.

The tremendous swells of the treacherous Southern Ocean, the highest and broadest waves on the planet, often threatened to engulf them. Yet another gale forced them to hove-to for 48 hours with a canvas cone sea-anchor dragging JAMES CAIRD’s head to wind and sea. She soon began foundering, not only from seas shipped but also under the weight of a build-up of ice on the hull and rigging. The men took terrifying turns to crawl out on the glassy decking to clear away the ice. Eight days out, Worsley snapped another sun-sighting, the crew holding his legs as he balanced on the pitching deck, with one hand clinging to an icy stay.

They were halfway to South Georgia, but the resilience of the men was wearing thin. One freezing night Worsley could not straighten his body after his spell at the helm, and the crew had to drag him beneath the decking and massage him before he could unbend. Yet another roaring gale brought sleet, then snow-squalls, and a tremendous cross-sea that was the worst so far. The sea-anchor tore away and was lost, so the helm now had to be manned full time. Around midnight Shackleton was at the helm and noticed a line of clear sky between the south and southwest. He told the men that the sky was clearing, but it was the white crest of an enormous wave. Shackleton wrote, “During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods, I had not encountered a wave so gigantic. It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted,

“For God’s sake, hold on! It’s got us!” and then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours.”

JAMES CAIRD, half-full of water, somehow survived, and the crew bailed for their lives. They limped on, and when Worsley glimpsed another sun-sight, he estimated their position to be 150NM from South Georgia. The navigation had been so “extraordinarily crude that a good landfall could hardly be looked for,” so they lay a course for the southwest, windward side of the island. If they sailed downwind of the island, they were doomed because they could not beat JAMES CAIRD back to the island.

Remarkably, after fifteen hellish days on the planet’s most savage seas and only four sun sightings, Worsley had somehow found the tiny South Georgia Island. The probabilities almost defy the imagination. Heavy seas made landing impossible, then another colossal storm front hit, “One of the worst hurricanes any of us had ever experienced.” For over 24 hours, JAMES CAIRD battled to stand clear of the coast, and when shipwreck seemed inevitable, Worsley wrote of

“Regret for having brought my diary and annoyance that no one would ever know we got so far. I doubt if any of us had ever experienced a fiercer blow than that from noon to 9 pm.”

The storm tore the tops clean off waves, and a 500-ton steamer was lost off South Georgia with all hands. The weather eased to a gale, and on 10 May “with infinite difficulty,” they managed to land at the entrance to King Haakon Bay. All six were so weak that their efforts to haul the JAMES CAIRD clear of the surf failed until food and rest had revived them.

Alexandra Shackleton, a dinkum replica of the JAMES CAIRD

The only help, the Stromness whaling station, was on the far side of the mountainous island that nobody had traversed before. Screws were extracted from JAMES CAIRD and inserted into the soles of boots as crampons. Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean set off, and they marched without rest, climbed 9,000ft, crossed the mountain range, slid down glaciers, and after 36 hours staggered and crawled into Stromness. Eighteen months before they had departed from there on ENDURANCE, and when the station manager realised who they were, he exclaimed, “These are men!”

The whaling station sent a boat around the island to collect Vincent, McNish, McCarthy, and the JAMES CAIRD. Worsley wrote, “Every man on the place claimed the honour of helping haul her up to the wharf.” Three months after departing from Elephant Island, Shackleton returned on the steam-tug YELCO and found all personnel still alive remarkably. They returned to civilisation in Chile on 3 September 1916.

Seven years later, Ernest Shackleton returned to South Georgia to lead another Antarctica expedition, but suffered a fatal heart attack on 5 January 1922. He was buried “In an island far from civilisation, surrounded by stormy, tempestuous seas, and in the vicinity of one of his greatest exploits.” Worsley and other members of the ENDURANCE expedition were also there and built a memorial cairn to Shackleton in the Grytviken cemetery overlooking King Edward Cove. When Frank Worsley died in London in 1943, friends scattered his ashes near the NORE Lightship at the mouth of the River Thames.