I’m Working On It

With the theme of the 2027 wooden boat festival (only eighteen months away) recently announced, I’ve been putting a bit of thought into where “Working Boats” fit into the tapestry of traditional boating in Australia.

As always with these things, the story that needs to be told is primarily about the people who worked and maintained these craft, and then the appreciation and admiration for the boats will follow. With that in mind here are three beautiful & short archival films from around the world, that evocatively remind us that the roots of our passion are labour not leisure.

Thames Lightermen

Photograph F J Mortimer. Royal Museums Greenwich

In the 1950s, Thames lightermen were skilled river workers who played an essential role in the movement of freight along the River, especially within the Port of London, which at the time was still among the busiest ports in the world. Their primary responsibility was to navigate and manoeuvre lighters—large, unpowered barges used to carry goods—between oceangoing ships and the docks, warehouses, or factories lining the river. Unlike tugboat crews, lightermen typically used long oars called sweeps, as well as poles, to guide these heavy vessels through the Thames’ tidal waters, often with extraordinary precision.

Most lightermen came from families with deep generational ties to the river. Entering the profession usually required a formal seven-year apprenticeship, during which young men would learn the intricacies of the river: its tides, currents, hazards, and working practices. Their work was overseen by the Worshipful Company of Watermen and Lightermen, a centuries-old guild established to regulate those who transported goods and people on the river. This apprenticeship was a matter of pride, and those who completed it earned a degree of respect among their peers and in the broader port community.

The work itself in the 1950s was still largely traditional and extremely physical. Lightermen moved all manner of cargo—from coal and timber to grain, building materials, and various imported goods. Despite the increasing use of diesel and steam tugs to assist with towing, much of the handling remained manual, and the job demanded considerable strength and endurance. Working conditions were tough. The Thames, with its fast tides and unpredictable weather, made every shift potentially dangerous. Work was dictated by the tides, so hours were irregular and could include nighttime and early-morning shifts, especially when the tide was right for upriver travel.

Lightermen were generally well-unionised, most commonly under the Transport and General Workers’ Union, and they were active in labor disputes, particularly during the post-war years when the docks were a flashpoint for industrial action. Although the pay could be decent, it came with the risks and challenges of physically intense, often cold and wet work. The 1950s also marked the beginning of a slow decline in the profession, as alternative methods of freight transport—particularly road haulage and the early stages of containerisation—began to erode the dominance of river trade.

By the 1960s and 70s, the use of lighters had diminished significantly as shipping operations shifted downstream to deeper ports like Tilbury. The lightermen’s trade, so long a vital part of London’s economic life, became increasingly obsolete. Nevertheless, its legacy lives on in the traditions, oral histories, and a few remaining practitioners who keep the knowledge and heritage of the river alive. Some lightermen continued into the late 20th century, working in more limited or specialised roles, and today the profession is remembered as a symbol of London’s working river culture.

Throughout their history, lightermen were known not only for their skill but for their deep, almost intuitive knowledge of the river. This was passed down orally rather than in books or charts, and to earn the “freedom of the river” was a badge of honour. It was a tough life, but for those who worked it, the Thames was not just a job—it was part of their identity.

How Dhows worked.

Tim Severin’s connection with Arab dhows was forged through one of his most ambitious and evocative historical expeditions: the Sindbad Voyage, undertaken between 1980 and 1981. Inspired by the legendary tales of Sinbad the Sailor from The Thousand and One Nights, Severin set out to discover whether such journeys—described in rich detail in Middle Eastern folklore—could have been based on actual voyages undertaken by Arab mariners during the medieval period. Rather than simply research the stories, Severin decided to live them.

To do this, he commissioned the building of a traditional Arab dhow, using entirely authentic materials and techniques. Constructed in the port town of Sur, Oman—an area with a centuries-old tradition of dhow building—the vessel was named Sohar, after the Omani port believed by some historians to be Sinbad’s hometown. True to historical methods, the dhow was built without nails or modern fastenings; instead, the planks were sewn together with hand-twisted coconut fibre rope, just as they would have been a thousand years earlier. It was a remarkable feat of craftsmanship and historical recreation.

Once complete, Severin and his small crew sailed Sohar along the ancient maritime trade routes that once connected the Middle East with India, Southeast Asia, and China. Their journey took them from Oman, across the Arabian Sea, along the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, past Sumatra and through the South China Sea, eventually reaching Canton (modern-day Guangzhou) in southern China. In doing so, they covered nearly 6,000 miles and proved that such long-distance sea voyages in traditional dhows were not only possible but highly plausible for traders of the medieval Islamic world.

Severin documented the entire experience in his 1982 book, The Sindbad Voyage, which details not just the perils and triumphs of the journey, but also the extraordinary skills of the Omani shipwrights, the richness of Arab maritime heritage, and the historical significance of the ancient trading networks. Today, the dhow Sohar is preserved and on display at Sultan Qaboos Port in Muscat, standing as a tribute to both Omani seafaring and Severin’s unique blend of exploration and historical inquiry.

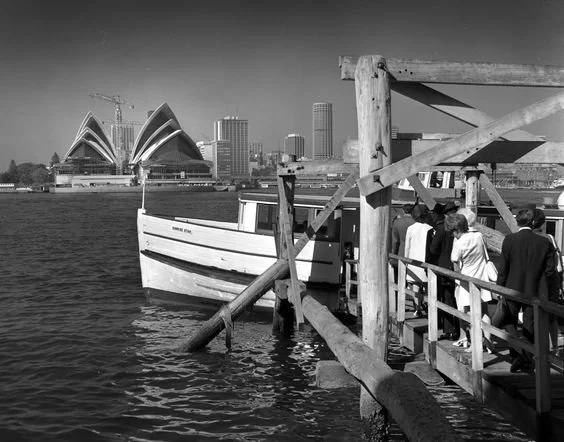

Sydney Harbour Working Boats

Made by The National Film Board 1953. Directed by Joan Boundy. The port of Sydney was one of the world's busiest, but it is not only the seagoing liners and cargo vessels that make it so; there are the little ships and boats that never go "outside" but spend their crowded days in a hundred different ways, doing the odd-jobs on Sydney's waterfront. This classic National Film Board film beautifully reflects the life of those that work on Sydney Harbour. While the film shows the busyness of the work carried out on the harbour, especially some of the less obvious jobs, it has a calm and relaxed pace that matches the gentle lapping of the waters and the repetitiveness of the tides. The film, set very much in a male dominated environment, was directed by Joan Boundy, one of the first female directors at the Film Board who directed several films there between 1951 and 1973. This film was also screened at the inaugural Sydney Film Festival in 1954.