Jesus was a Sailor

‘Jesus was a sailor when he walked upon the water, and when He knew for certain only drowning men could see Him, He said all men will be sailors then, until the sea shall free them’

Fred went below to his bunk and prayed.

For the last fifty years the Indian ocean has brought refugees from Asian conflicts to Australia by boat. Asian resorts are now filled with young Russians hoping to avoid conscription and the war in Ukraine. Things were much the same 120 years ago in the Tsar’s empire. In 1907 Paul Sproge fled Russian controlled Latvia to Germany for the same reason and found his way to Australia. During the 1930’s economic depression he hoped to improve his lot in America and once again set sail, across the Pacific. This story is a companion to Russell Kenery’s tale about Bernard Gilboy who sailed from San Francisco fifty years earlier reaching Fraser Island.

Fred Rebell

Paul Sproge was born 1886 in Windau, Russia (now Ventspils, Latvia). This was a Baltic Sea port and ship building town originally part of the German Hanseatic League that traded across the Atlantic and down to Africa. After the failed Russian revolution of 1905, the Tsarist regime reasserted power as Sproge finished school and started work. The bank clerk was a determined pacifist and didn’t want to be conscripted in the Tsar's army and fled to Germany. He purchased documents in a Hamburg café from a deserting sailor Fred Kabull. Neatly adjusting the surname, Paul Sproge became Fred Rebell. He signed on to a ship as a coal stoker before stowing away for Sydney in 1907.

He first found work with a railway construction crew in Maitland near Newcastle before moving to Western Australia. There he won a land grant at Balbarrup, 350k south of Perth. While working at odd jobs in a saw mill he slowly cleared the land to farm. Emily Krumin answered his newspaper advertisement in Latvia and travelled out to Perth. In 1916 they were married and had one son. The farm was sold in 1925 and Fred worked as a carpenter in Perth while seeing another woman, Elaine. Emily finally left Fred in 1928 and filed for divorce. Fred moved back to Sydney.

By 1930, like many people, he was desperate in the depths of the depression. He decided to emigrate by ship or sail to the United States. Its unclear how he came up with the idea. Perhaps he was inspired by the American Harry Pidgeon who had sailed alone around the world between 1921 and 1925. Pidgeon had no previous experience and was called the ‘library navigator’. Fred was a great reader and loved the 19C American writer and fireside poet Henry Longfellow. Perhaps he was dreaming of the ‘Song of Hiawatha’ and his Minihaha. He also knew H G Wells ‘History of Man’ and the 1890’s science fiction novel ‘The Island of Dr Moreau’ about a shipwreck in the southern Pacific. The US Consulate in Sydney declined to issue a visa making a ship’s passage impossible. Undeterred and with no money, Rebell made his plans. He would just sail there anyway.

Elaine

After doing odd jobs in Sydney Fred had saved some money to buy a boat. He called her ELAINE. She’s described as a Sydney half decked regatta boat, designed for day sailing on the harbour. She was 18ft LOA with a 7’ beam and only 20” of freeboard. She was clinker planked with a shallow draft and gaff rigged. Boats of this era usually had a steel swinging plate and shifting lead ballast. Rebell set about fixing things. He doubled the number of frames and increased the sail area. He made a small cabin forward by stretching oiled tent canvas over sprung steel arches. His bunk bed was canvas slung between wood frames. There was no protective deckhouse with the tiller area fully open, no engine nor bilge pump. Fred was sure he could bail with a bucket.

ELAINE under sail. Whereabouts unknown

Preparation

Rebell like Pidgeon, studied navigation in the public library, purchasing a 70year old navigation manual at a street stall. He copied what he thought might be useful maps from an old Pacific atlas when many of the islands and reefs had not yet been discovered, let alone surveyed. He sailed ELAINE on Sydney harbour to practice manoeuvres he’d read about in sailing manuals. With no money, Fred made the navigation instruments himself. He later wrote;

‘First of all, I need a sextant built with the utmost care, given that the slightest inaccuracy can lead to errors of hundreds of miles in the calculated position. For mine I used a few pieces of iron from a bottle crate, a small telescope used by boy scouts cost me a shilling, an old hacksaw blade and a stainless-steel penknife. I cut the knife into pieces for the sextant mirrors and ground them flat with emery paper and polished them with jewellers paste. The hacksaw blade was used for scaling the angles. I chose it for the regularity of the teeth and it could bend into a regular arc. I chose the radius of the curve so that each tooth corresponded to half a degree’.

‘Then there was the log to measure distance travelled. This instrument essentially consists of a float with fins. When trailed in the water, it assumes a rotary movement proportional to it, and by virtue of a flexible joint activates a tachometer on board. I built my float with a piece of broom handle and added aluminium fins on angles from its axis. One full revolution was equal to thirty centimetres. As a tachometer, I converted an old clock so that each mile travelled corresponded to one minute of its dial. When I tested the log, I noticed it had an error of 20%, but in a measuring instrument an error does not matter when it is known and constant. I had a cheap boy scout’s compass and two Westclox pocket watches as chronometers’.

Fred stocked the boat with 6 months of dry and tinned provisions. These were stored in five gallon petrol cans (22 litres). Eight cans were set aside for fresh water and one was for a small alcohol stove in the bottom, to reduce risk of fire. He spread the gear under the bow deck and around the boat. When fully loaded the freeboard was further reduced. Fred makes no mention of a life vest, tether, flairs or any other safety equipment. There was no one to rescue him anyway.

Fred Rebell’s homemade sextant, log and chronometer.

The Pacific

Having few friends he told no one he was leaving. Unlike many adventurers who make much of publicity, Fred quietly set sail from Sydney on December 30, 1931. It’s not clear if America or perhaps Latvia was his destination. He had nothing to lose as an economic refugee dreaming of a new life and visiting his childhood home.

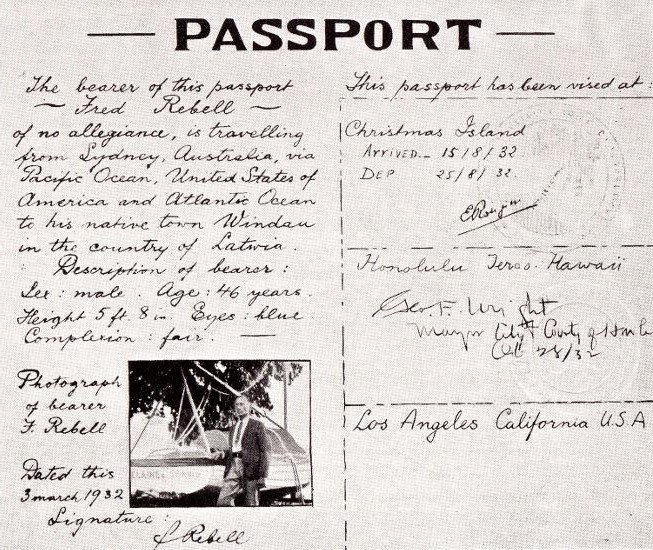

He sailed east towards the Kermadec Islands in fair winds before turning north to Fiji. With no radio communication or weather reports, on day 38 ELAINE was hit by her first gale. Fred got all the sails lashed down and tied off the tiller. Under bare poles, Fred went below to his bunk and prayed. The centreboard case gave way and it’s a mystery how long he ‘lay ahull’ while managing to bail and stay afloat. On day 60 in early March 1932 a small battered skiff entered Suva harbour. The rhumb line route is some 1800nm but who knows how far Fred had sailed to suit the wind. Without any papers it took some time for Fijian officials to verify the story of this lone mariner from Sydney. Once confirmed Fred was given a welcome party in his honour. The locals were surprised he didn’t share their kava, drink or smoke. They assisted him to make repairs to ELAINE and restock. Predicting future problems with authorities, Fred fashioned a homemade passport declaring himself of ‘no allegiance, travelling from Sydney Australia to his native town Windau in Latvia’.

Fred and ELAINE in Suva harbour Fiji 1932

On April 20 he sailed for Apia in Samoa arriving 36 days later. A direct route is 650nm. There he rested and re-fitted before continuing the 1100nm passage north to the Fanning Islands, half way to Honolulu. He sailed via Danger Island (Pukapuka, Cook Islands) resting for eleven days before continuing to Christmas Island (Kiritimati Kirabati). In the light winds ELAINE was only covering 35 miles a day. Later he claimed to manage the long lonely days by reading Longfellow’s poetry and the Bible. He caught only the fish necessary for his next meal and cooked bread by steaming the dough. By August when he sailed into the protected lagoon on Kirabati, Fred was covered in blisters, suffering from chronic food poisoning and the constant glare and tropical heat.

A month later after some R&R, Fred upped anchor and headed north for Hawaii. The 1100nm passage proved comparatively easy with fair and favourable winds. He arrived in Honolulu in good physical condition. Once again American authorities were not happy with this sailor travelling without proper documents. They rejected his passport but decided to issue him with seaman’s papers valid for a 60 day stay in America. At least the mayor of Honolulu signed the passport. Fred describes the final 2200nm leg to California;

‘The run from Honolulu was a nightmare. In the last weeks of December I battled constant gales. The turbulent sea threatened to smash my boat to pulp. On two occasions the little boat was wallowing more than half full of water. My arms were so tired from constant bailing, I could not raise them above my shoulders. Once again, I strapped myself to the bunk and prayed. Providence has been kind to me. On January 8, 1933, I struggled into Los Angeles harbour and tied up at Cabrillo Beach. After one year and one month, my voyage was over. I had sailed the Pacific’.

It's hard to fathom what drove Fred, a man of frugal means, to imagine and complete such a dangerous voyage. His character was that of an unassuming and disciplined ascetic. His Christian faith gave him spiritual strength while one report described him as having ‘the physical resistance and insensibility almost of an animal’.

Fred’s homemade passport dated this 3 March 1932

America

Fate proved unkind to Fred Rebell. Three days after arriving in Los Angeles, ELAINE broke from her mooring when a gale hit the harbour. With many other boats she was washed onto a beach. Fred thought she was fixable but a US Navy launch doing recovery work was thrown against ELAINE damaging her beyond repair. Two days later, he was arrested by immigration officials as his 60 day permit had expired. He couldn’t post the bond so was jailed. His remarkable story was taken up by the press in Los Angeles and New York. ‘This self-taught man who sailed from down under in an 18ft open boat single handed, is a modern Vasco da Gama.’ Rebell was released after a week and the US Navy agreed to compensate him 85 dollars. He spent two and a half years in California before a US Treasury cheque arrived.

ELAINE after the storm in Los Angeles harbour 1933

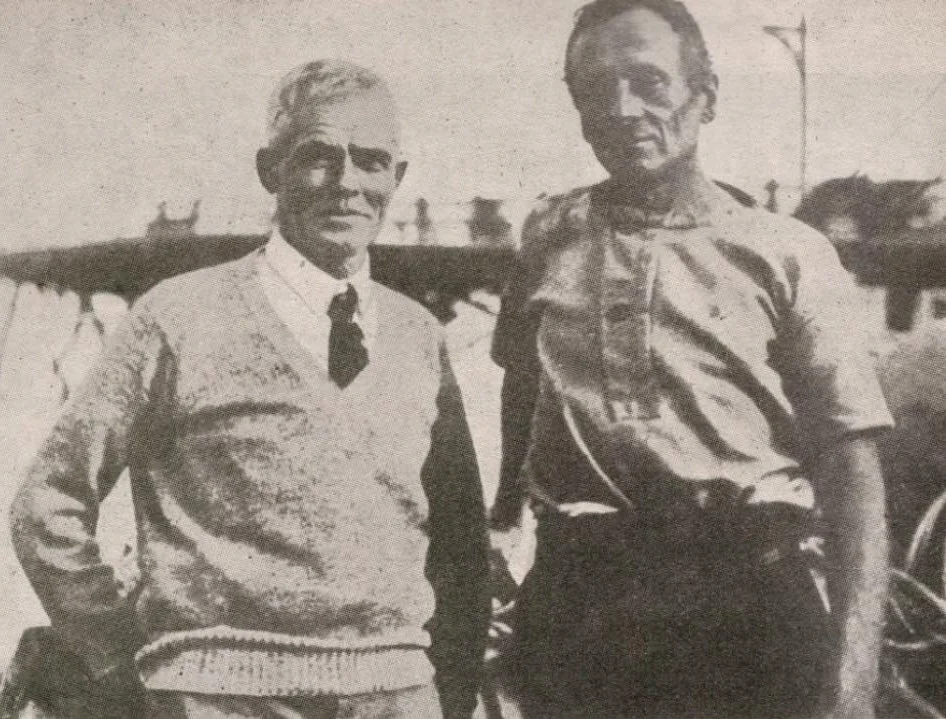

Fred with Walter Pidgeon. Cabrillo Beach California 1933

Postscript - the Return

Fred Rebell did get a passage back home to an independent Latvia at the expense of the United States. He spent time on the family farm in Ventspils writing his journal. His meagre savings were almost exhausted mailing the manuscript to publishers without success. The remaining money was spent on a 22ft boat SELGA. He fitting her out with a closed cabin and concrete keel intending to sail back to Australia. In 1937 he left from Leipaja sailing across the Baltic, through the Kiel Canal and into the North Sea bound for England.

The anchor dragged off the Suffolk coast while he slept washing SELGA onto a shingle beach near Aldeburgh. Word got out in the village and a journalist visited Fred who was making repairs. She read his manuscript and phoned a London publisher. The work was accepted after three days and he was paid an advance on his royalties.

He sailed on down the coast and into the English Channel heading for the Canary Islands. A storm struck SELGA entering the Bay of Biscay and a large wave picked up the boat and turned it over. Rebell was trapped in the cabin. ‘For more than 20 seconds she remained upside down throwing me against the bulkhead. The concrete keel proved itself leaving me to bail and pray until the storm blew itself out’. Fred limped north to Plymouth harbour thinking the boat was not suitable for ocean sailing. ‘How I wish I had the trustworthy ELAINE’.

Fred Rebell decided to join a 50ft yawl out of Guernsey, the REINE d’ARVOR. The family who owned the boat were migrating to Australia and sailing down the Atlantic, then via Panama canal and across the Pacific. They welcomed the experienced sailor aboard. After another story of adventures and rebellious pick-up crew, Fred steered the yacht through Sydney heads in December 1939, some seven years since he was outbound on ELAINE.

Once again authorities intervened. Without a passport, Fred could not leave the boat in Sydney until two Government departments had made inquiries. Having been absent from Australia for more than 5 years his domicile had lapsed. He offered his homemade passport and his Nansen certificate aka ‘the dog ticket’. After a few days on the yacht, this was accepted by the Minister for the Interior. The Nansen was issued by the League of Nations, a precursor to the United Nations. It was devised to allow stateless people and refugees to travel in search of work and safe home. The Melbourne Herald was able to report; ‘a Modern Ulysees finds haven in Australia’.

Escape to the Sea

Fred’s book was published in 1939 by John Murray (London) and translated to French in 1948. He was in good company as Murray had published Byron, Jane Austin’s Emma, Conan Doyle and early travel books. Most famously, Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’ and his journals from HMS Beagle. Fred settled in Sydney working as a carpenter to support his calling as a Christian pamphleteer and Pentecostal lay preacher.

He was tracked down and interviewed by Seacraft Magazine in 1957.

‘I am the founder and sole employee of the Tempe Evangelical Tract Service. Since i returned to Sydney, I have never sailed a boat. In fact the only time i’ve been aboard a ship is on a harbour ferry. I’ve had enough sailing, it’s a dog’s life’.

Graham Cox writes;

‘Rebell ended his days living in men's shelters in Sydney dying in 1968. I liked his book as he was obviously a competent seaman and inventive person. He was a bit eccentric and deeply religious, both of which may account for his relative obscurity. In those times, there may have also been some prejudice against him for being a foreigner from northern Europe with traces of an accent’.

Fred at work in his later years.

Fred on Film

Fred and ELAINE in San Pedro, Los Angeles. He amiably explains his navigation gear and log prop after a visit by a shark.

Introduction from Suzanne by Leonard Cohen.