“Seal Families Sleeping in the Sun will be my Christmas Present”

Bernard Moitessier

Christmas for most takes place on solid ground. Even those heading off into the rigours of the East Coast & Bass Strait races, have the day ashore to contemplate, before the annual challenge is taken up. But Christmas day at sea seems to be a melancholy time; Loneliness, confected frivolity, and the worries of an unknown future.

This Christmas we bring you accounts of 25th December at sea from three of our favourite maritime authors. And while you’re indulging in just one more roast potato give a quick nod to those afloat in 2023 on this special day.

ERLING TAMBS-The Cruise of the TEDDY

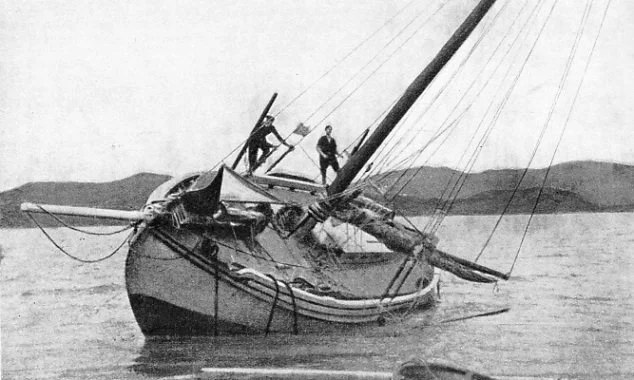

In 1928, Erling Tambs and his bride set off from Norway in the old pilot cutter TEDDY, with no sextant or barometer, and only one and sevenpence in small change. They had no special destination and no urgency, but it was the beginning of three years of adventurous and often accident-prone sailing amongst islands in two oceans. At Las Palmas the crew was increased by the birth of Tony, and in New Zealand by a daughter, Tui. This is truly one of my all-time favourite accounts… Perhaps because Mr Tambs and his new wife had a dog with them called “Spare Provisions” or maybe because his vessel is almost as beamy as it is long or maybe because the story ends in a tragic and horrendously understated traumatic wreck on Kawau Island in New Zealand’s Hauraki gulf…one of the greatest cruising grounds in the world. Or maybe it’s because of the subtle evocative design genius of the dust jacket….

The passage below takes place in late 1930 somewhere between Samoa and Tonga.

For nearly three weeks, sails and tiller remained practically untouched. As though guided by a higher power. The boat found her own way among the islands, and even the wind seem to change so as to accommodate itself to our course.

In spite of the seasons, the sky remain permanently serene; Never had we experienced such a long spell of lovely weather.

At noon on Christmas Eve, my temperature had risen to above 105. Even on the point of fainting, I was hardly able to drag myself on deck to take my daily sun altitude. My subsequent struggle and calculating proved utterly exhausting, and the results were rather vague, giving our position as being some 30 miles to windward of the Minerva Reefs, two extensive and very dangerous barriers of coral visible only at low tide.

I had turned in again. Julie was washing clothes on deck, with Tony keeping her company. Amid the monotonous rumble of the washboard I heard the low murmur of their voices. The dog lay on the floor beneath my bunk, whimpering softly. A marlinspike swinging with the gentle motion of the boat, tinkled with the clear tone of a bell. Each detail in my surroundings, I observed with minute distinctness but as if from a great distance, and as if it were something strange, which had not the slightest connection with me.

Suddenly an exclamation of alarm from on deck, roused me from my stupor. Almost at the same instant my wife appeared in the companion in great agitation to announce that we were surrounded by reefs on all sides.

I struggled out of my bunk. The pain in my arm was awful- and as I staggered towards the companion I stumbled and fell heavily upon my sick arm against the steps.

Well, it was not pleasant but it was the cure. From then on my arm became better. On Christmas day, my temperature for the first time, dropped below 103 and thence forward, in spite of the flu which carried on an unequal fight for a few days longer, I made rapid strides towards recovery.

As to the reef which threatened us on all sides, they presently revealed themselves to be large schools of porpoises playing at a distance.

This was our first Christmas at sea. My wife surprised me with a large tin of tobacco, and I surprised her with a package of her favourite cigarettes. She had certainly bought both, and I had been aware of their existence all along, but that did not lessen our surprise or render the presents less appreciated.

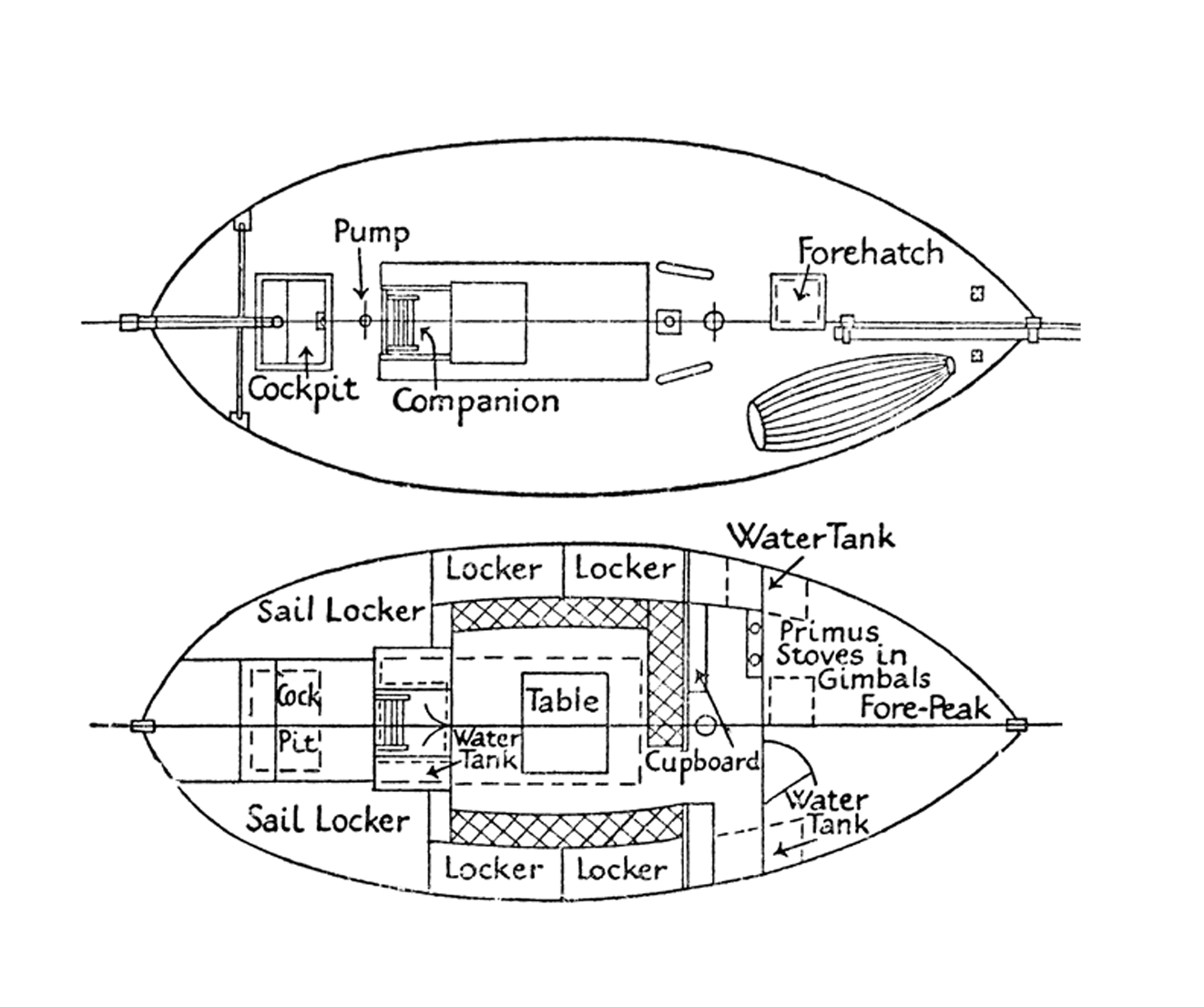

The TEDDY’s deck plan and accommodation

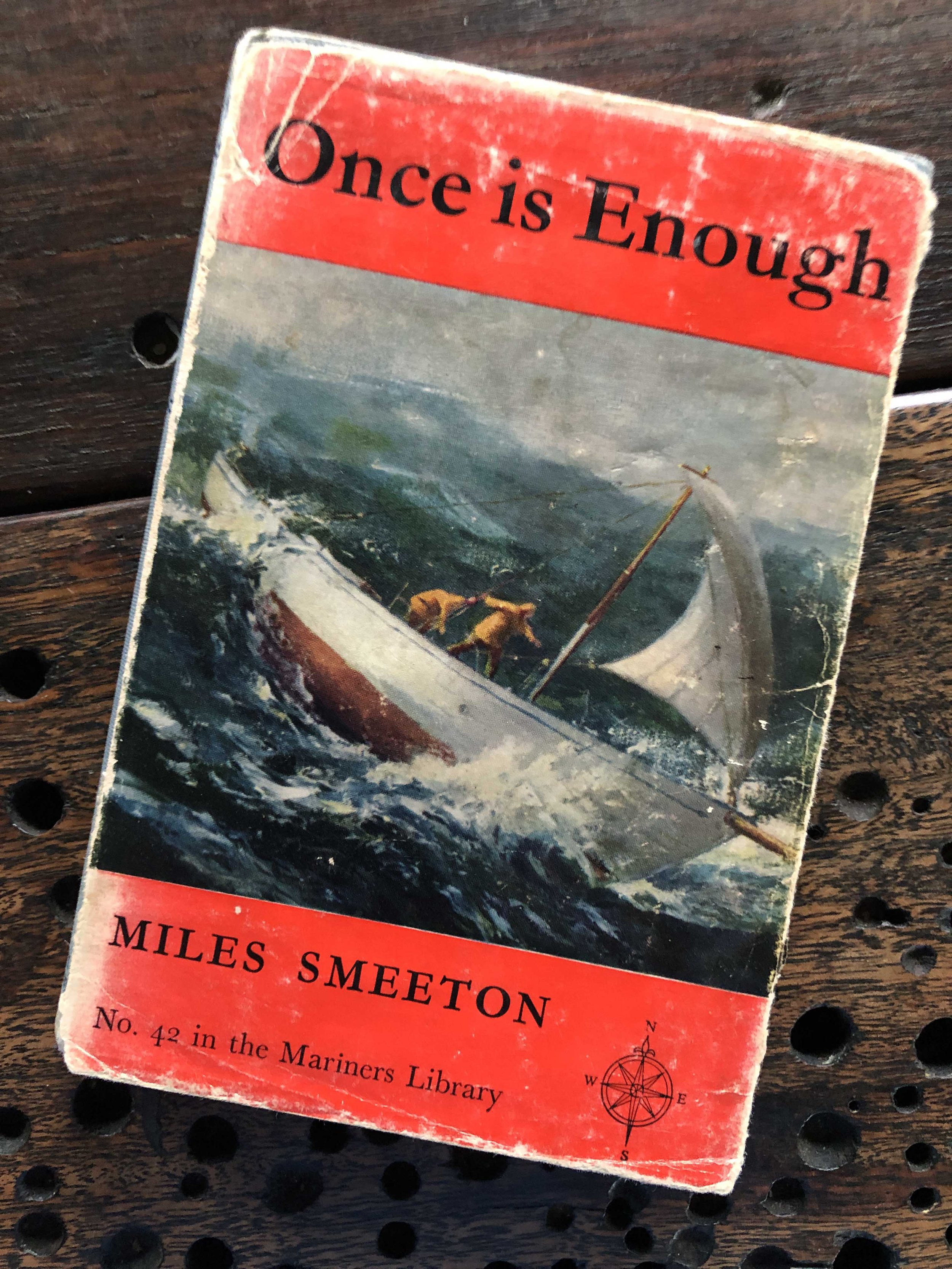

MILES SMEETON- Once is Enough

In 1951, Beryl and Miles Smeeton bought the 46' bermudan ketch TZU HANG on a visit to England. The boat had been designed by HS Rouse and built in Hong Kong in 1939. The name was believed to mean "under the protection of Guanyin", the Daoist goddess of the sea and protector of sailors. They returned on the boat to British Columbia, learning to sail on the way. In 1955 they sold the farm and sailed on Tzu Hang for Australia.

Chapter 1 takes place on the Yarra River in 1956, Melbourne (during the Olympic Games) a few miles from where I’m now writing.

In December 1956 they departed Melbourne to visit their daughter Clio at school in England, intending to follow the old clipper route. The journey would take them eastbound around Cape Horn, a voyage that at that time had very rarely been accomplished in small boats. They were accompanied on the boat by a young friend, the Englishman John Guzzwell, who had been circumnavigating the world in his self-made boat on a voyage later recounted in his book “Trekka” as well as by their Siamese cat, Pwe.

After leaving Port Phillip heads on 23rd December they discovered that their gooseneck was broken and decided to pull into Westerport Bay for repairs.

Port Phillip Heads are narrow gap, only a few 100 yards across, through which all the vast area of Port Phillip Bay pours out its waters during the ebb tide, and through which the sea comes boiling and bubbling on the flood.

If the wind is against the ebb, the passage can be very dangerous. It was slackwater at the heads at 1030 so that we didn't have to get up early. That night TZU HANG swung quietly to her anchor, as motionless, as if she was still at the wharf in the Yarra River. The tide chattered busily along her planking during the night, first out to sea, and then into the bay, and then out to see again. And in the last hour of this tide, we hauled in our anchor, started the engine and motor down the misty channel.

The buoys came out of the murk, one after another and we checked their numbers against the chart. The mist cleared, and we could see the Heads and as soon as we were on the right bearing, we turned to run out. As we pass the signal station at Point Lonsdale, we saw the signal for the tides change from the last quarter to the first quarter; It was exactly slack water, and there was no ripple on the surface. On the port hand there was the black and red rusting hull of a steamer wrecked on the shoals and ahead the sails of two yachts. As soon as we were through, we stopped the engine and got up sail ourselves, but the wind was very light from the south, and we made very slow progress on port tack.

By the evening we were becalmed and the main sail was flopping about as we rolled. We handled all sail. About midnight, there was a slight breeze again, and I hosted the main. As I did so the boom dropped out of the gooseneck and I found that the bronze fitting on the boom had fractured. The gooseneck was frozen with rust and the bronze fitting had been bending but as we were close haulded we had not noticed it.

Now it had broken and, as we were still within easy reach of port, it was just as well to have it repaired. We should have checked and oil the goosenecks before leaving. We turned in for the rest of the night and early next morning set off for Western Port, a few miles down the coast and up a long arm of the sea.

The wind strengthened and as we ran up the long channel against the tide, we were followed by the two yachts that we had seen leave the heads before us. We tied up to a wharf at a small harbour called Cowes, leaving an anchor out to hold us off the wharf if the wind shifted. This cause great distress to the captain of a steam ferry, which brought holidaymakers over to Cowes. Although he hadn't asked me to move it, he came up to me complaining angrily, as if I'd already refused. I was only too anxious to move it when I found that there was a chance of the ferry fouling the line. We walked up through the village, a steep little hill, and there was a cold fresh wind blowing, which made the cotton frocks and the shirtsleeves of the Christmas visitors look out of season.

At the top we found a garage and we were able to get the boom fitting repaired. But it was late when we got back to the ship. And as the wind was blowing strongly down the channel, we decided to leave on the tide next morning. We had just started dinner when there was a loud crash against the bow and something started to scrape down the side of the ship.

“Heavens, what on earth’s that said Beryl. Sounds as if we've got a visitor. “

We all scrambled up on deck as quickly as possible. Include Pwe who hates being left absolutely alone below. One of the yachts which had been tied up ahead of us had broken its stern line and it swung round putting its bowsprit through the pilings of the wharf and breaking it off. We fended her off TZU HANG, and while I jumped on board to look for another line, John climbed up on the wharf to get her bow line. He towed her back into position, and we made her fast again with the best of a bad lot of line that I found in the cockpit. The wind was really blowing up and it looked as if we might have to move away from the wharf.

We settled down to dinner again, but it was a dreary Christmas Eve without Clio. Last Christmas there had been an inappropriate tree in the boat, and decorations and presents and all the litter of Christmas and now, not only were we missing the person who had made it all necessary, but we ought to have been at sea and not stuck in Western Port. John had an innate understanding of people's feelings and the good sense not to intrude upon them. He was neither unnaturally hearty or over sympathetic. In fact, he was just himself. When Beryl offered him some brandy butter to go with his plum pudding, he said rather gloomily, “Brandy butter, made with margerine and rum.” We all began to feel better.

Before the plum pudding was finished, there was another bump against the bow and we found that the same yacht had joined us again. The owners arrived while we were disentangling her. They hosted the mainsail and sailed her round into the sheltered water behind the angle of the pier, where they anchored. An hour later TZU HANG began to bump against the pilings. It was raining and as black as night can be. The lights shone on a wet deserted wharf, and the sounds of a dance band came across from the hotel.

We untangled ourselves from the network of lines and hawsers and pushed off into the night groping for a nine fathom patch with Beryl trying to take the bearings of the wharf lights on the compass and John swinging the lead line. We could not go where the other yacht had gone as there was insufficient water. And in the end, we dropped the anchor and 12 fathoms with 40 fathoms of chain and hoped that we'd be able to get it up again in the morning.

On Christmas Day, the wind blew strongly down the channel and we stayed at anchor very busy making everything still more secure for the journey ahead. And it was not until Boxing Day morning that we set about getting the anchor in again in time to sail with the tide.

For some time we couldn't break it out but at last it came away covered with thick blue clay. We unshackled it and let the chain go into the locker, after making the end and we lash the anchor down and fixed the ventilator over the chain navel. We expected to be well battened down for much of the way, and hoped that the ventilator would give us sufficient fresh air in the forecabin.

Meanwhile, we were motoring up the channel and in spite of a very rough short sea with the wind against the tide, we were making good progress.

By midday we were passing the lighthouse at the entrance to the lock, and we could see little coloured specks of holiday visitors along the cliff top. We kept under power until we were far enough out to clear Seal Rocks on the port tack, on our course for the south.

“I wonder how many rocks there are in the world called Seal Rocks” John said

“Let's hope the next Seal Rocks will be called Los Lobos” said Beryl. “That's what they call them in South America.”

The climax of the book takes place when approaching Cape Horn. The yacht was pitchpoled by a rogue wave. Beryl, who had been on the helm, was tossed from the boat and injured. TZU HANG was dismasted, partially submerged, and the topsides were severely damaged, but the three sailors managed to sail the damaged vessel to Chile, where extensive repairs were undertaken. In 1957, a year later, Miles and Beryl departed again to round Cape Horn. However, in approximately the same position, beset by storms, another dismasting took place. Again, they managed to make the coast of Chile, and TZU HANG was shipped to England for repairs. After repairing the vessel, they made a multi-year eastabout circumnavigation. In 1968, they again attempted Cape Horn, westabout, and successfully rounded.

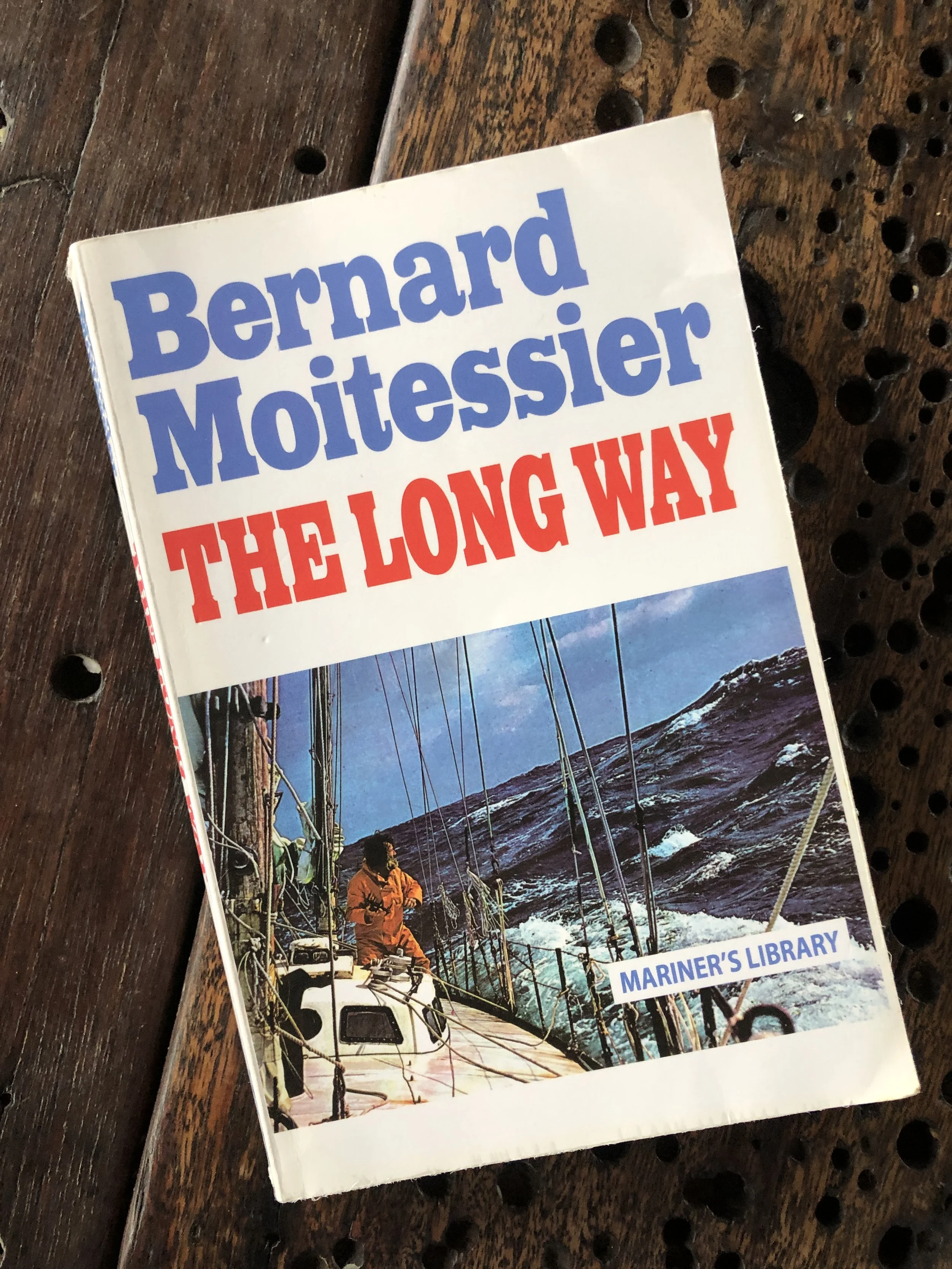

BERNARD MOITESSIER- The Long Way

First published in 1973, “The Long Way” is dated, in a melancholy way. It’s a personal story of Moitessier’s participation in the first Golden Globe Race, a solo, non-stop circumnavigation rounding the three great Capes of Good Hope, Leeuwin, and the Horn.

Some moments in “The Long Way” jar painfully. Moitessier’s departure from his wife and children. His avoidance of them throughout his time away. Also, the amount of stuff he chucks over the side of the boat – to save weight. He does not have a contemporary sensibility. He gleefully smokes his way around the world. He is not a saint. But he’s on a genuine quest for something. Hence his famous message to the Sunday Times:

‘Dear Robert: The Horn was rounded February 5, and today is March 18. I am continuing non-stop towards the Pacific Islands because I am happy at sea, and perhaps also to save my soul.’

The passage below takes place off the bottom of New Zealand in late December 1968 having a few days earlier made a film and letter drop in Tasmania, near Bruny lighthouse.

At dawn the wind had nearly died. The sea begins to subside. A black ball with wide eyes looks at me, dives, reappears, it is a little seal. My first since the Galapagos. He swims around the boat, goes off, and then comes bounding back across the water with infinite grace. I do not think there is anything in the oceans as lithe as a seal. This one must be a youngster, he is not the least shy.

And now it is Christmas. Flat calm. The sea is almost flat as well, under the bright sun. The little seal (or his brother) is back playing near the boat, but not jumping like yesterday. From time to time, he sticks his hind flippers out of the water and slowly waves them as if to say ‘hello-hello’. If the water were not so cold, I would go say hello too. In the Galapagos, the baby seals would practically rub up against us. They were so friendly and inquisitive. Their parents did not like it and occasionally chased us out of the water. I can't tell whether this one is very young or belongs to a small species. He can't be over four foot long.

Complete sunbath on the 46 parallel south! The sails flap a little, the air is warm, almost hot, with a light breeze from the north. All things considered, I'm all right here. Still, I hoped to spend Christmas east of New Zealand.

I had even planned if the weather were really nice to spend it close to Dunedin or Molineux, within a New Zealand yacht that would just happened to be around. I would have hailed him with my loudspeaker:

“Ahoy there. Want to have a bite with me? I have champagne for Christmas and wine by the barrel.”

“Champagne? French Champagne? French wine.?

“Heave too 100 yards off and come over in your dinghy.”

“Okay, I'll bring my gin along to just in case your Champagne and French wine don't do the trick.”

That's the way it is -you make up little stories alone at sea. Sometimes they come true.

The air is amazingly transparent, the wake barely discernible on the smooth sea. Several times JOSHUA passes through strange large clumps of seaweed. It's not really seaweed, but the crossed fore-flippers of seals sleeping on their backs. Once awakened the big ones dive, reappearing much further off. The little ones come over to play every time, but worried mothers round them up and lead them away.

The seal families slipping in the sun will be my Christmas present. Especially the little ones-They’re so much nicer than electric trains. If their parents let them I wouldn't be surprised if they tried to climb aboard… we could all have Christmas dinner together.

Taking advantage of a fine sun and also of Christmas. I unwrap the smoked York ham specially prepared by Loick and me by Marsh and Baxter, at the request of our friends Jim and Elizabeth Cooper.

I had kept it in the hold under its original wrapping, saving it for these cooler latitudes where it would be safe from heat waves.

The ham is perfect, without a trace of mould after four months in a humid atmosphere. Hey! What's happening to me? I suddenly start drooling like a dog with a choice bone under his nose. I must have had a long standing ham deficiency… on the spot, I snap up a piece of fat the size of my wrist. It melts in my mouth.

For lunch, I fix a sumptuous meal. I pour a two pound can of hearts of lettuce, well rinsed in sea water, into a pot where a piece of ham has been simmering with three sliced onions, three cloves of garlic, a little can of tomato sauce, and two pieces of sugar.

John Gau was the one who explained that you should always add a little sugar to neutralise the tomatoes acidity.

Then I take a quarter of a canned camembert, cut it into little cubes and sprinkle it over the hearts of lettuce, along with a big piece of butter.

The aroma wafts all through the cabin as the pot simmers very gently on the asbestos plate. Cook it very, very slowly because of the cheese. That is another secret. I learned onboard OPHELIE with Yves Joville. One evening he asked me to stay for dinner and Babette simmered some cheese in a pot for a long, long time. It turned out to be hors d'oeuvre, main course and dessert.

We stuck pieces of bread on a fork and dunked them right into the pot, drinking white wine the while. It was so good that if there had been a Mauritian present he would have called it a Manila duck’s climax, because when a Manila duck has finished, he flops on his back and just lies there, unable to move.