The 930-Year-Old Dugout Canoe

By Duncan Blair from his Traditional Sail Website

A Native American 28-foot canoe estimated to be 1,000 years old was recovered from southeastern North Carolina’s Lake Waccamaw.

Since starting this blog just over two years ago I have come to appreciate the fundamental importance of dugout canoes. They may not often sail but they are about as traditional as you can get.

I think that they should be understood as foundation stones of human creativity in the rich history of boat building. Rafts may have their place, but dugouts, to me, represent a higher level of esthetics, creativity and function. See Photo above.

My wife ran across this photo on-line about two weeks ago and called it to my attention. I have been thinking about it ever since. Nine hundred thirty years ago was was the year 1093. To put this date into perspective, that was 27 years after the Norman Conquest (1066) of England by William the Conqueror.

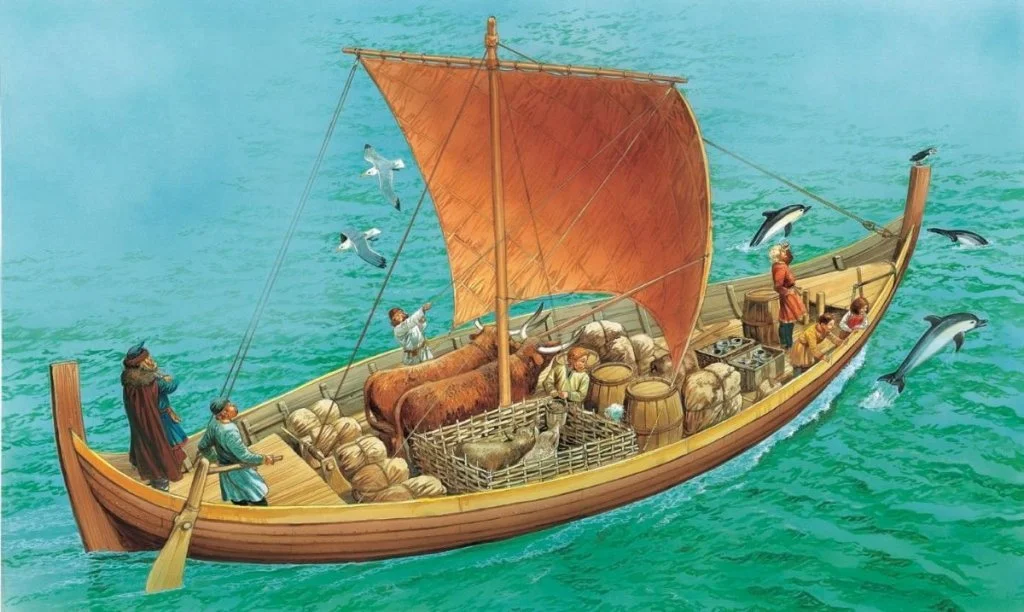

William’s boats, his invasion fleet, sailed across 30 miles of the English Channel, from Normandy, France. They were very similar to the Viking longships and smaller Norse trading vessels, called Knarrs, of two or three centuries earlier.

Illustration of a Norse Knarr designed for carrying freight

As all boats do, they reflected the materials and technology available at the time. They were clinker-built, their planks split from logs with wedges and sledges, not sawn. Being split gave the planks greater strength and flexibility.

The planks were fastened with wooden pegs, called trunnels, and iron nails made in Norse forges. Many of the tools used to build the boats were made of iron and steel, also locally forged. At the same time, to the North West of France and England, the Irish and the Welsh were building and using Coracles.

Coracles are still being made. They are often circular in shape, with interior framing made of slender branches with animal hides, often goat skins, stretched over the frames and stitched together. The stitching is sealed with wax or bitumen or animal fat. Think back to when you last read Treasure Island and you may remember the marooned sailor, Ben Gunn, whose goatskin coracle Jim Hawkins used to paddle out to the schooner Hispaniola.

In both examples, Norman invaders’ boats and Welsh/Irish peasant boats, form was determined by function, available materials and technology. The Norman boats, although crude by modern standards, were outstanding, in 1066, in their ability to carry knights in armor and their horses, as well as their ability to sail 30 miles, before the wind, across La Manche, the English Channel.

THE DUGOUT CANOE

The dugout shown in Photo #1 above, was found in Lake Waccanaw, in what we know as North Carolina. It is also clearly representative of time, place, function available materials and technology.

MATERIALS

The dugout is 28 feet long and looks like it is about 18 to 24 inches wide. Unlike the coracles and the Norman boats it was not “built”—not constructed by assembling separate pieces of material to create a hull.

This dugout, like all dugouts, was “sculpted”—literally carved—dug out—of a tree trunk. This tree may have fallen by itself in the forest or it may have been intentionally cut down by humans using tools powered by muscles and maybe also using fire, as a tool, to help weaken and drop the tree.

TECHNOLOGY

The Norman boats were products of the Iron Age, characterized by mining coal and iron ore, then smelting the iron ore into useable chunks from which tools, weapons and armor could be forged. In North America, including the future North Carolina, these technologies were completely absent and unknown.

The Roman legions never invaded North Carolina, bringing their technologies and engineering skills. North Carolina was also on the wrong side of the Atlantic ocean, located where it, and the rest of the Western Hemisphere, could not be directly influenced by the social, cultural and technological sophistication of Judeo-Christian and Islamic influences found in Europe, the Near East and North Africa.

TOOLS

The Norman shipwrights had axes, saws, adzes, hammers, chisels and nails—lots of nails. The North Carolina dugout sculptors had fire and sharp rocks; either locally available flint, obsidian or chert, or similar stone that they got through trading.

They also had, or traded for, shells. Big, thick shells that could be broken up and sharpened with a whet stone. Remember that the warlike and very creative and prosperous Calusa nation of South Florida used shells as both tools and weapons.

Students of dugout sculpting believe that once the tree was felled, it would have been stripped of all its bark, then have its future top and bottom surfaces determined by its curvature, if any. Then a series of cuts would be made across the long axis of the log, across the top surface.

These cuts would then be connected by hacking away the wood between each of them, leaving a roughly flat surface that would become, with more sculpting, the interior of the canoe.

To facilitate the removal of the wood, a series of small fires would be laid on the flat, rough surface. Carefully watched and controlled by the sculptors, the fire slowly burned away, or at least charred, the wood along the entire upper surface.

The charred wood could then be removed by more careful hacking and scraping with stone or shell tools.

This series of procedures is the sculpting process in its simplest form—the removing of material in order to create and reveal the desired form that lies beneath.

FORM

Q. Why make such a long and necessarily narrow canoe which appears to be very difficult to maneuver and turn?

Q. Why not lash shorter logs together in order to make a raft that would not require burning and hacking?

I can only offer my guess to answer these questions.

My guesswork answer:

A raft would have to go over, ride up and over, any grasses, reeds or other aquatic vegetation in the lake. The long, narrow canoe could go through, not over, any vegetation, which would allow the people in the canoe to fish more quietly and to reach out with hands and baskets to harvest desirable plants and seeds, ex. wild rice.

CONCLUSION

What I find to be most interesting and compelling about the dugout canoe from the 10th century is it’s inherent “boatness”. When you find one of these things buried in the centuries old mud of a lake bottom the first thing you think of is “It’s a boat!”

Despite its age, condition, location and shape it is instantly and clearly recognized as a boat.

And as a boat it is also recognized to be a human solution to the challenges of transportation, travel and food gathering over water that have occurred in all societies and have been met in a fascinating variety of ways—always reflecting the materials, tools and technologies available.

I hope that you enjoy thinking about these things as much as I do.

PAU

Duncan Blair

As always, all ideas and opinions expressed are mine alone.