The Baby Boat Review

By Graham Cox

The Vertue design by Jack Laurent Giles has always been one of my favourite small bluewater cruising yachts. If I could find one in perfect condition (and afford it) that was built in solid Burmese teak, copper-roved and bronze-fastened, I’d be in sailor’s heaven. That might sound like an impossible dream today, but in the 1950s and 60s, the Cheoy Lee boatyard in Hong Kong was building Vertues to these specifications. One of them, Vertue Carina, was built for South African yachtsman, Bruce Dalling (later famous for his participation in the 1968 OSTAR) in 1966, and sailed to Durban, South Africa.

Vertue Carina was the first small yacht that I laid eyes upon. In December 1966, at the tender age of 14, I found it moored alongside the International Jetty in Durban. I’d gone down there on an idle whim, to look at an old Colin Archer ketch, Sandefjord that had just completed a 22-month circumnavigation (who says Colin Archers are slow!), and whose story had been written up in local newspapers. Vertue Carina was nestled daintily beneath Sandefjord’s massive bowsprit.

Vertue Carina on fore-and-aft moorings in Durban in 1968, when I used to paddle my canoe out to inspect every inch of the yacht.

I knew nothing about yachts in those days and might not have noticed Vertue Carina if I had not fallen into conversation with one of the visiting international yachtsmen, Dr. David Lewis, whose catamaran, the cold-moulded plywood Rehu Moana, was rafted alongside Sandefjord. David suggested that a Vertue would be the ideal boat for a young chap like me to sail the world on, though I remember looking dubiously at little Vertue Carina. It looked like a toy in comparison to Sandefjord.

David went on to tell me about his own double crossing of the North Atlantic in 1960, when he competed in the inaugural Singlehanded Transatlantic Race, later known as the OSTAR, in Cardinal Vertue. He went on to say that Cardinal Vertue had recently been sailed around Cape Horn by a young Australian called Bill Nance.

It meant nothing much to me at the time, but several months later, on 21 October 1967, Robin Lee Graham sailed into Durban on his 24ft sloop, Dove, and I had my famous lightbulb moment, when the future trajectory of my life became apparent. Singlehanded ocean cruising was the only game in town, I decided, and any yacht over 30ft was decidedly decadent. It is a position I hold to this day. After reading David Lewis’s book, The Ship Would Not Travel Due West, and Humphrey Barton’s Vertue IIIV, the Vertue design became the benchmark by which I judged the suitability (for my purposes) of all yachts.

From then on, Durban Central Library and the International Jetty became my favourite haunts. I read all the classic ocean voyaging books, and met some wonderful characters and salty boats from all corners of the world on the jetty. Vertue Carina had been moved out onto a fore-and-aft mooring in the yacht basin, so I acquired a canoe to paddle out and inspect every inch of the boat. There was another Vertue there too, Aldebaran, built locally by Henry Vink, aboard which he had cruised to Mauritius and back. I lusted after both of them, but the exquisite Cheoy Lee joinery of Vertue Carina, and the way her name and port of registry, Hong Kong, were carved into the transom, captured my heart.

In the summer of 1969-70, I finished high school, abandoned the idea of going to university, to my parents’ dismay, and began scheming of the quickest way to get afloat. I badly wanted one of those Vertues, but acquiring one seemed an impossible financial hurdle. At this time, I was introduced to John and Karen Cross, who had just bought VERTUE CARINA, and were preparing for a voyage to Europe. To my delight, we became good friends, and I was invited aboard the boat on numerous occasions. I was even there on Durban’s northern breakwater to wave goodbye when they sailed for Cape Town and beyond in late summer.

Vertue Carina in Durban shortly before leaving in early 1970.

We corresponded for a couple of years, and I thrilled to read of their adventures, but after I moved to Australia at the age of 20 in 1972, we lost contact. They were in Falmouth, England, the last time I received a letter from Karen. I later heard on the sailor’s grapevine that they’d had a son, Peter, in Falmouth, and left to sail back to South Africa when the boy was just four months old. For a long time, I wondered what had become of them after they returned.

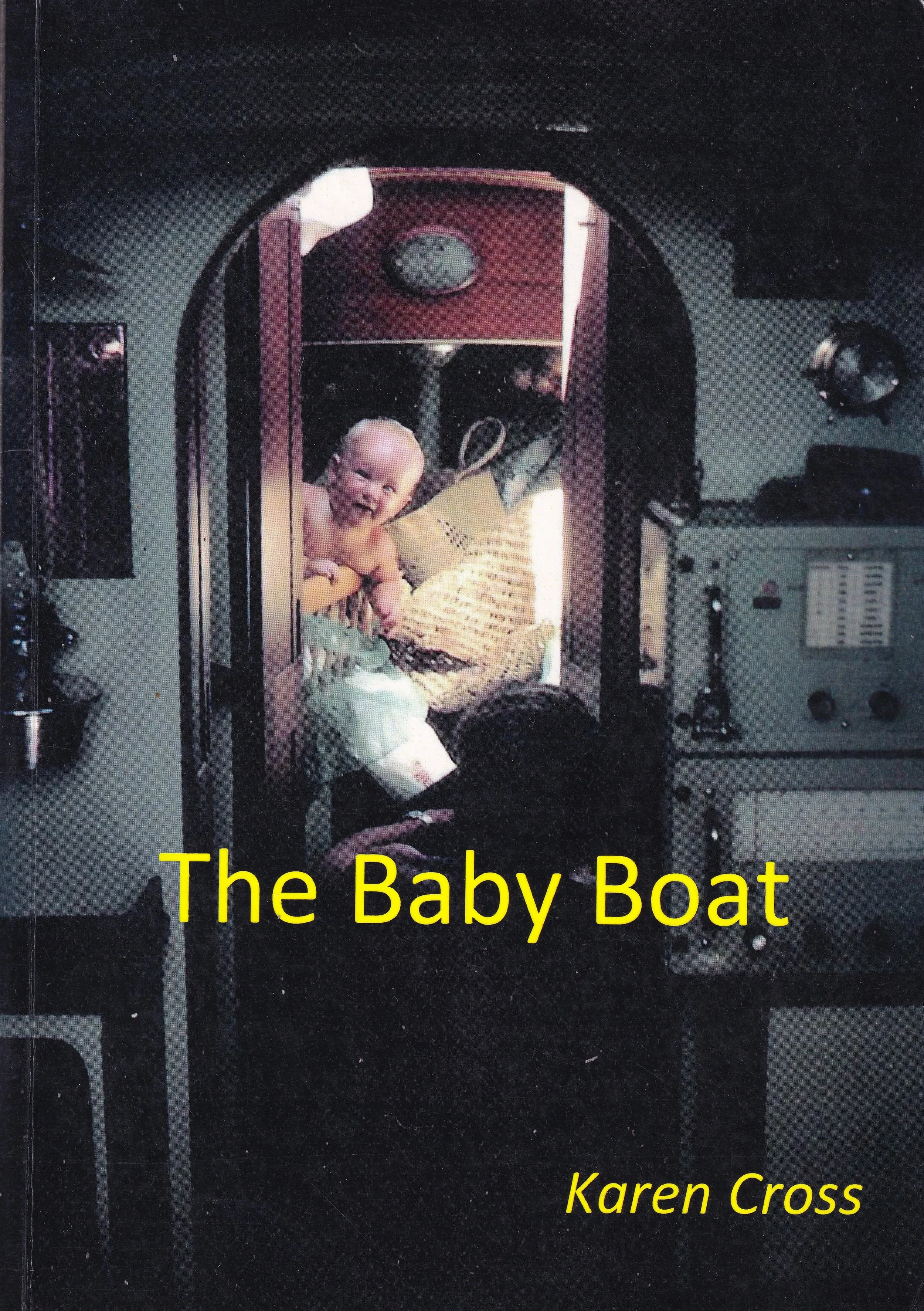

A few years ago, I was thrilled to discover that Karen had written a book about their voyage, The Baby Boat, and managed to secure a copy from a second-hand bookseller. The book has recently been republished by Rockhopper Books in South Africa. Reading The Baby Boat was a great joy; it took me back to my youth, and filled in all the details of their voyage that I'd so often speculated about. It was such an impressive voyage, filled with determination and courage. One fascinating aspect of reading The Baby Boat was to watch John and Karen grow from neophyte sailors to seasoned ocean voyagers.

When Vertue Carina set sail from Durban, it was the first time John and Karen had been to sea, apart from a brief trial sail aboard Aldebaran with Henry Vink. On that trip, Karen had been violently seasick, and was soon incapacitated once again, along with their friend, Willy Mowlam, who was accompanying them on this initial leg. Luckily, John was not seasick, and this fortunate fact almost certainly allowed them to persevere, though their learning curve was still steep. By the time they staggered into East London, 250nm down the coast, Karen had lost four pounds in body weight, and the genoa had been ripped in half during a vicious squall.

They had another drama on the next leg to Port Elizabeth, when faced with a strong SW gale. While entering Algoa Bay, the boom guy rope became wrapped in the propeller, and John dove into the sea to clear it, before motoring safely into port. It was already becoming evident that John had the resilience and resourcefulness needed to cross oceans. Their trials were far from over, though, as they faced a 70-knot storm after leaving Port Elizabeth, and ended up returning there for several weeks.

Once they left PE on 23 March 1970, accompanied by Karen’s brother, Richard, and a friend, Keith Davidson, they stopped briefly in Mossel Bay to dodge another gale, then hastened on to Cape Town. Karen had finally found her sea legs and began to enjoy the voyage. She noted with great satisfaction the day that she managed to peel some potatoes while the yacht rolled along. They arrived in Cape Town on 4 April.

Vertue Carina cleared out of Cape Town for Saint Helena Island on 22 April, farewelled by American voyager, Fred Davenport and his daughter, Circe, from the 46ft ketch, Karen Margrethe, a boat the author remembers well from the four years it spent in Durban. In the book, Karen describes departing from Cape Town as the worst day of their lives! They had been inspired by Eric Hiscock’s Around the World in Wanderer III, and John had studied the theory of celestial navigation, along with everything else needed to sail to Europe. Also, Vertue Carina was a well-found, veteran ocean cruising yacht, but would they actually find little Saint Helena Island, a tiny speck measuring 10 by 5 miles, in the vastness of the South Atlantic Ocean? It is understandable that they felt great trepidation setting out, and a mark of considerable courage that they persevered.

John Cross looking a little apprehensive as Vertue Carina leaves Cape Town for Saint Helena Island.

Probably due to nerves, John was also sick for the first few days out of Cape Town, and they lay prone in their bunks as the yacht looked after itself, rolling along downwind to the NW. Eventually they recovered, John more so than Karen, and they began to eat again. John also took his first-ever sextant sights of the sun. Initially, the sights did not tally with his ded-reckoning position, but after he carefully reworked the ded-reckoning, the positions tallied to within 10 miles, and from then on, he had no further problems with navigation.

They had a few close calls with ships in those early days, including two mysterious encounters at night with vessels that chased after them and shone spotlights on them. It was the height of the cold war era, and John was convinced they were Russian spy ships. I know from my own experience how easy it is to get spooked on a dark night at sea.

They both continued to feel weary and off-colour, and the incessant rolling of the yacht, plus the clanging and rattling of items in the lockers, drove them to distraction. They stuffed towels in the lockers in an attempt to quieten things down. Adding to their exhaustion, it was difficult to get the home-made self-steering gear to work, forcing them to do a lot of sail-changing in an attempt to balance the boat, plus hand-steering at times.

However, Vertue Carina was making good time, despite many days of overcast, squalls and sloppy seas. Their worst day’s run was 45nm, when three days out from Cape Town, and their best a very decent 130, not bad for such a small boat. Vertues have always been famous for their high daily averages when making long ocean passages.

On the evening of 8 May 1970, John estimated that they were about 25nm south of the island, and they hove-to for the night. There were no shore lights on the south side of the island in those days – it might be different now that there is an airport on that side of the island, not to mention that most yachts will have GPS/chart-plotters aboard – so they were uncertain of what the morning would bring. I should add that John was navigating with a vernier sextant made in 1850, and he wondered about the knocks it had taken during the passage.

At dawn, the sky was filled with black clouds, but soon John discerned that one of the clouds was a little firmer than the rest, and it quickly formed into the island. After 17 days, and a daily average of 100nm, Vertue Carina had arrived at Saint Helena Island. John’s navigation had been perfect, and elation swept through them both. The doubts and misery of the preceding weeks were swept away, never to return.

Karen says they loved Saint Helena more than any other landfall during their voyage. Besides the natural exhilaration of making your first offshore landfall, the island was quaint, and many of the people extremely gracious and friendly. Karen also notes wryly that teenagers are the same the world over, from the giggling girls who came to watch her doing her laundry, to the boys who tied their dinghy painter up in dozens of difficult knots, after being refused permission to borrow it for a jaunt around the bay! They later made their peace with the boys, allowing them to use the dinghy in return for rowing out an anchor and taking Karen ashore. They also met the famous Colonel Gilpin, and his equally well-known housekeeper, Mrs Yon, who made a point of offering hospitality to visiting yacht people, and giving them fresh produce from his garden.

From Saint Helena, they voyaged happily onward, confident now in their ship and themselves. Seven perfect, sunny days took them to Ascension Island, 700nm further north, with the ship running along steadily under twin headsails poled out. Karen at last felt well at sea, and never experienced seasickness again. For the first time, she spent considerable periods of time in the cockpit. Ascension was a less welcoming island than Saint Helena, largely because of the antisocial behaviour of two yachts that had visited the island a few weeks earlier, and because heavy ocean rollers made getting to and from the yacht difficult. Nonetheless, some of the locals took a shine to them, and they managed to enjoy themselves after a strained start.

From Ascension, they made the bold decision to sail directly to England, instead of stopping at the Azores Archipelago, as the majority of cruising yacht did, and probably still do, when en route from Cape Town to England or Europe. What is even more astonishing is that they completed the passage in 56 days. Eric and Susan Hiscock took 51 days and 11 hours to sail from Ascension to Fayal in the Azores, at the end of their first circumnavigation in 30ft Wanderer III, a boat that could be described as a larger version of the Vertue class.

Rolling down the tradewinds under twin headsails. Note the oil (kerosene) navigation lights at the forward end of the doghouse. Karen notes that lighting them in the cabin made the interior sooty. Vertue Carina was a simple boat, with a small petrol engine.

The first days out of Ascension were a joy, running WNW before steady tradewinds under twin jibs. John and Karen sat on the foredeck, mesmerised by the water swishing past the bows, and realised they were now thoroughly enjoying this life. The tradewinds tend to be more easterly here, closer to the equator, and they reached their waypoint at 25°W without difficulty, before turning north to tackle the doldrums, or the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone, as it is now called. They passed through this area without too much difficulty, then had a wet and rough beat north against the NE tradewinds, discovering numerous deck leaks, before finding the westerlies that took them into the English Channel.

This long passage felt interminable at times, especially during periods of calms and squalls, but it was filled with joy at others. Their moods are captured well in detailed log entries reproduced in the book, or diary entries really, as they recorded far more personal material than one usually finds in these accounts

One of the reasons for pushing north as quickly as possible was their plan to meet Karen’s Danish grandfather, Pokka, in Denmark that summer. Because he had jumped the gun somewhat and was already there, they did not have enough time to enjoy the delightful waterways of Falmouth Harbour as much as they desired, not to mention the new friends they’d met. After a quick refit, they carried on to Denmark.

Vertue Carina on the slipway in Denmark, late 1970.

Vertue Carina was left in Denmark for the winter and they returned to work in Falmouth. While removing the mast before hauling the yacht out of the water for storage, the mast snapped in two at the spreaders. Bruce Dalling had told them that he thought the mast had been damaged during his pitchpole in the Mozambique Channel in 1966, but John’s examination of it when they bought the yacht only showed a few black marks near the spreaders, and it all seemed solid enough. In fact, they had sailed all the way to Europe with a rotten mast.

In the spring of 1971, with a new mast rigged, John and a friend, Derek, sailed the boat back to Falmouth. A few months later, while cruising to the Scilly Isles, Karen discovered she was pregnant. Peter was born on 29 March 1972, and by the time he was three months old, Vertue Carina was outward bound for France and beyond. If they left it any longer, the seasons would dictate staying another year in England. After sailing to France to meet John’s parents, they set sail from La Rochelle on 9 September 1972. The vague intention was to head across the Atlantic to Brazil, before turning north to Panama and the Pacific. Peter was now four months old.

John Cross holding Peter just before leaving La Rochelle for South America.

There was a lot of criticism from some quarters about taking such a young baby to sea, and whether or not breast-feeding would provide Peter with enough nutrients in those early, critical months. Karen was forced at times to stick to her reasoning, not helped by her own anxiety about the forthcoming voyage, but right from the start Peter loved life on the boat and throve.

In good weather, the cockpit provided a fine playpen for Peter, in the days when he was too young to climb out of it and get into mischief.

He even had a gimballed cot to keep him safe when both John and Karen had to tend ship. The rest of the time the whole boat was his playpen, and he loved exploring the cockpit. They also discovered that Peter was a great ambassador, and brought them many new friends. People adored him. It was while they were in Gibraltar that the crew another yacht, Black Rose, began calling Vertue Carina ‘The Baby Boat’. Black Rose also had a three-year old boy aboard.

Eventually Peter outgrew his gimballed cot and it was converted into a leeboard to hold him in his bunk, though he often spent time in Karen’s arms or with John in his bunk. Karen in particular often felt exhausted by the extra attention Peter required on top her duties sailing the boat, cooking, etc, but they had a largely uneventful passage to the Canary Islands, where a considerable cruising fleet had gathered. All the other yachts were bound for the Caribbean.

I found it fun reading about the cruising yachts they encountered in various ports, some of whom I’d met when they passed through Durban in previous years. Others I was to meet later. The cruising community in the 1960s and 70s was a close-knit group, who often sailed relatively small, traditional timber yachts. In 1973, Miles Smeeton, of Tzu Hang fame, titled his last sailing book, The Sea Was Our Village.

From there they sailed on to Sao Vicente in the Cape Verde Islands, which in those days was a desperately poor and unhygienic place, where they were harassed by some of the locals, and where they had difficulty finding even basic fresh provisions. As always, though, there was someone they met who took them under his wing and helped them as much as he was able. Both John and Peter fell ill the day after they left, but fortunately quickly recovered.

They set sail from Sao Vicente, bound for Recife, on 9 December 1970, meaning they would be at sea that year for Christmas. Vertue Carina was reaching fast in gusty conditions, with the occasional wave breaking over the deck and filling the cockpit, often soaking the washed nappies and other items they were attempting to dry in the sun. Peter, however, was delighted with life at sea, bouncing around on a makeshift bed between the bunks, or squeaking for the attention of his weary parents. He was progressing now towards eating adult food, and happily munched on things like sausages or Karen’s home-baked bread, which he also delighted in breaking into crumbs.

For a while, he fell sick again, with heated cheeks and loss of appetite. Alone at sea, with no means of communicating with the shore, John and Karen worried, giving him ampules of medicine to manage the infection. John even declared, emotionally, that it was no life for a child, and he wanted Karen and Peter to fly home from Brazil. But, once again, Peter recovered quickly, and was soon his usual, bouncy, demanding self. With more experience as a mother in later years, Karen was able to look back and realise he was most likely just teething.

Passing through the doldrums proved, as ever, to be a hot and trying affair, with sails slatting and chafing, and all of them suffering from heat rashes. Above them, the moon sometimes shone with waxy brilliance, and they thought of the Apollo 17 space mission, which was currently up there. One night, while Karen was reading by torchlight, and Peter was standing up, balancing between the bunks, she became aware that he was fascinated by the movement of the torch light, trying to catch it when it came near him. With a pang, she realised that he was going to miss his first Christmas, and how much he would have loved all the flashing lights and baubles ashore.

One day they were visited by a large group of dolphins, some black, some speckled, and some grey in colour, which leapt and cavorted around the boat for an hour and a half, often leaping out of the water and somersaulting through the air. Karen stood in the main hatch, holding Peter, who was mesmerised by the creatures. This is the sort of experience that can only be gained by voyaging across oceans in small vessels.

Christmas Day dawned cool and relatively calm, so they had a proper Christmas after all. Karen was able to bake a tinned chicken they had aboard, with all the trimmings, followed by Christmas pudding and Karen’s home-baked mince pies. They decorated the cabin with tinfoil, and by the way that Peter licked the roasting dish clean, his eyes gleaming out of a greasy face, grinning with delight, Karen knew the meal had been a success.

21 days later, on 30 December 1972, they came ashore in Recife, Brazil, leaving on the 11th for Salvador. In both places, they enjoyed the hospitality of excellent yacht clubs and friendly locals, but Peter fell sick again, breaking out in a rash and sometimes crying loudly. The locals said it was just a heat rash, but John once again raised the question of whether this was a suitable life for a child of his age.

John and Karen securing the headsails after arriving in port.

On top of this, some of their family in South Africa were expressing great interest in meeting Peter, especially Karen’s 11-year-old sister, Christine. After a lengthy discussion, it was decided that if they could find the money, Karen and Peter would fly home for a visit, and John would sail to Panama and find work. Later, Karen and Peter could join him there and they would continue into the Pacific. But the money they hoped to get from John’s pension fund in South Africa never materialised, and they didn’t have quite enough to cover the fares.

The die was cast, and they sailed south to Rio de Janeiro, arriving eight days later, just before the 1973 Cape to Rio Yacht Race fleet, with the intention of sailing back to Cape Town from there. In Rio, they met a number of old friends and boats, including John Sowden on his 25ft sloop, Tarmin, who had been in Durban in the summer of 1969-70. John Sowden remarked that Peter was one tough kid, after observing him fall down Vertue Carina’s forehatch, only to be suspended by his harness. Peter was getting more active every day, getting into everything and having to be continually monitored.

By this time, they were almost out of money. Luckily, some of the South African yachts that were being shipped back after the Cape to Rio race gave them a large quantity of their excess provisions. They sailed south to the beautiful Ilha Grande islands for a few days, then, after posting their last letter home on 22 February 1973, they set sail on their most audacious passage yet, non-stop through the Southern Ocean to Cape Town, passing south of remote Tristan de Cunha Island, in order to take advantage of the prevailing westerly winds in those latitudes.

What followed was one of the greatest Vertue voyages ever made. 53 days later, on Easter Monday, 23 April 1973, exactly three years and one day since they had departed Cape Town, Vertue Carina slipped back into the harbour and berthed once again at the Royal Cape Yacht Club pontoon. They had weathered storms, endless headwinds, calms, injury and illness, and had to severely ration their food near the end. At times the cockpit was filled with breaking waves, and poor, battered Vertue Carina began to leak badly, including through the chainplates, which flooded some of their lockers. Working on deck was a dangerous, wet experience. It was an extraordinary passage, and this last chapter of Karen's book would be worth the purchase price alone.

John, Karen and Peter Cross on Vertue Carina, shortly after their arrival in Cape Town at the end of their 53-day passage from Rio de Janeiro.

John and Karen now live in Simonstown, near Cape Town. They sold Vertue Carina upon their return, but, by coincidence, the recently-restored boat is now moored in the same marina where they keep their latest vessel, Hamba, a modern cruiser-racer. They have three sons, Peter, of course, plus Ivan and Graham. Graham is an offshore sailor, who, at the time of writing had recently passed through Torres Strait on the way to Indonesia with his partner, Megan Ward, nearing the end of their circumnavigation.

Karen says that, in many ways, their life is divided into the period before Vertue Carina and the time that followed. They often go and look at the brave little boat that took them on such a grand adventure, and which wrote another chapter in the storied history of the Vertue design.

Vertue Carina anchor. From the back cover of The Baby Boat.

Graham Cox has been appointed as guest race commentator for the McIntyre Mini Globe Race (MGR), https://minigloberace.com/ and his memoir, Last Days of the Slocum Era, is available as a paperback book from Amazon, or as an ebook from Amazon or Kobo.