The Lost Loot of Lima

Melbourne…A town that gets a day off for a football match! It’s either a sign of decadence, a decline of the Roman Empire sort of thing, or an acknowledgement that sport is really a necessary surrogate for latent tribalism… our last opportunity to express irrational biases, unfounded prejudice and appreciation of controlled violence, before “bad behaviour” gets shut down forever.

Well the Old Dark Navy Blues exited the competition the week before, and with mid 20 degrees C forecast for the whole weekend, and my SWS co-editor over in Adelaide competing in the South Australian Women’s Keelboat Regatta, the opportunity presented itself to find the most remote little bay in Port Phillip, a body of water that has a 5.5 million people living on its edges.

My destination was the notoriously shallow Swan Bay on the Bellarine Peninsular.

(In the 1990’s they had a windsurfing school down there, but the learners kept running aground.)

The 25 mile trip down the bay from St Kilda is always a good time for contemplation. The views are not spectacular. There’s no harbour bridge to serenade you on your way, or dramatic cliffs to escape… just a thin diminishing and growing 360 degree strip of land, interrupted by the teeth of the city skyline, and the pimples of the You Yangs and Arthur’s seat.

But Port Phillip has its own charm, more slowly acquired than instant glamour of the waterways of the worlds great city harbours, Sydney, Hong Kong and San Francisco.

Swan Bay can be accessed either via the cut at Queenscliff, (but the depths and a bridge only allow progress as far as the QCYC) or via a shallow opening at the Northern end which has a ridge that needs to be crossed at high tide to acess a “pool” of deeper water, which remains sheltered from all directions except the east

Timing our arrival, with high tide, the dog and I proceeded gently over the shallow sand bank, watching the depth drop to 0.4 of a meter under the keel. (There have been thousands of occasions when I have thanked Philip Rhodes for his centreboard design during our 22 years of custodianship)

Once into the “pool” the depth dropped to two and a half meters under the keel, and I dug the anchor well into the hard shelly sand after a couple of failed attempts. The peace that surrounds a boat at anchor as soon as the engine is finally turned off, is therapeutic beyond any new age spa treatment! There are nearly 200 bird species that live in or visit the Swan Bay and most of them seemed to be within a few hundred meters of the boat. All the favourites were there … The Pacific Gull, the Black Swan (after which the Bay was named), the Australian Pelican, the Little Pied Cormorant, and so many others I couldn’t name.

A simple meal, a glass of red, an absorbing book, the crackle of life under the hull and the occasional thud of the anchor chain on the bow roller as the tide turns. It’s a restorative way to spend an evening; the leading lights of Queenscliff just visible over the lowly Swan Island, a few channel markers flashing in unison, a full moon to light the night.

Grand Final Day dawned but the intsead of football the Treasures of Swan Bay were on my mind.

From the Museum of Lost Things

Like any good buried treasure story, this one starts with a pirate: Benito ‘Bloody Sword’ Bonito.

Bonito was Spanish, and made his name in the early 19th century as the feared captain of the ‘Relampago’ (‘Lightning’). From his hideout on a small Pacific Island, Bonito and his crew stalked the west coast of the Americas, plundering ships laden with riches from the New World.

Their most daring feat is known as ‘The Loot of Lima’.

During the Peruvian War of Independence (1809 – 1826), the Spanish authorities attempted to evacuate a substantial treasure from the cathedral in Lima. Among the many valuables: four life size statues of saints, made of gold and encrusted with jewels.

Lima was about to be lost to the Peruvian insurgents, the Spaniards wanted to move the treasure by sea to a safer location. Bonito intercepted the ships, captured the loot, and headed for his island hideout. But he was already a wanted man. The Relampago was spotted by two British man-o-wars, and a lengthy chase ensued. Blown far off course by a storm, Bonito became lost. When he regained his bearings, he found himself off the southeast of Australia.

The Relampago in Pirate’s Cove, Wafer Bay, Cocos Island,by Montague Dawson

Bonito put into Port Phillip Bay, then uninhabited by Europeans, and anchored in a sheltered cove. He then had his cargo put ashore in long boats. Bonito’s men had found caves in the cliffs above the bay, and he used these to hide his treasure. To further obscure the location, the ridge above the caves was blown up with gunpowder, closing the entrance.

Bonito then put back to sea. His English pursuers reacquired him and the chase resumed; this time, the Relampago was run down. Battle was joined, but the pirates were outnumbered and soon beaten. Rather than surrender, Bonito committed suicide, shooting himself with a pistol. His crew were captured, and later imprisoned. Pirate stories were popular in the 19th century, and Bonito’s dramatic tale of plunder and pursuit was often told.

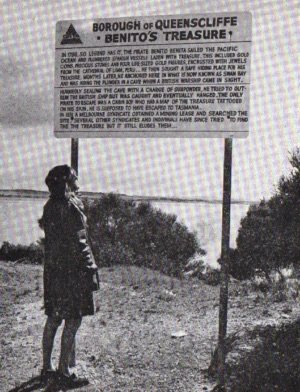

In June 1953, a visiting tourist found a silver coin on the beach in Swan Bay. The coin was old and its provenance unknown. A faint outline of a lion was visible on one side, some experts thought it may have originated in England, during the 18th century rule of Queen Anne. The discovery triggered another wave of interest in Bonito’s missing treasure. The local council even saw it as an opportunity to increase tourism. Signs were erected around Swan Bay, recounting Bonito’s story, and shire councillor L. Klegg proposed erecting billboards around the state.

‘Come to Queenscliff and find the treasure!’ he said in a newspaper interview, estimating the value of the horde at 20 million pounds.

Scores of amateur treasure hunters duly made their way to Swan Bay, to once again try their luck. Several of these were interviewed by the press, claiming they had discovered lost clues, or secret treasure maps.Another syndicate was formed and deployed a large steam shovel, to excavate an underground chamber they claimed to have found. But despite the media coverage and many thousands of optimistic searchers, once again nothing turned up. After a few years, with no further developments, interest in the story ebbed away again. The odd fossicker would still make their to Swan Bay, but the treasure appeared to be permanently lost.

And there the matter may have rested.

But there is one final twist in the legend of the Queenscliff treasure: both Bonito, and the Loot of Lima, are completely made up. You can see the problem on the billboard the council erected.

The sign has Bonito’s flight to Port Phillip Bay occurring in 1796; this is ten years before the Peruvian war of independence even started, and 25 years before the evacuation of Lima – where the treasure was meant to have originated – occurred.

How to explain these discrepancies?

A quick google search for ‘Benito Bonito’ reveals: not very much. Nothing by way of a formal bio, not even a Wikipedia page. For a real historical figure, one attached to exciting Pirates-of-the-Caribbean style exploits, this seems unlikely.

It turns out, Benito Bonito is actually a literary fiction; a tall tale cobbled together from fragments of real stories, and embellished in the re-telling. And his treasure is invented as well. Benito Bonito appears to be the creation of a Queenscliff local named John Karisimo. An early settler, Karisimo was a former sailor, known by his colourful nickname, ‘Stingaree Jack’.

Karisimo would regale other locals with tales of his life at sea, one of which involved him serving as a cabin boy on a Spanish ship. In this version, Karisimo met the eyewitness; a fellow sailor who had served under Bonito, seen the treasure being hidden in Swan Bay, and been the one to escape when Bonito was apprehended.

Karisimo had drawn a map based on what he was told, which was tattooed on his arm.

But when people were unable to follow his directions to the treasure, Karisimo claimed to have moved it. He died, without having revealed where.

The forecast for Sunday morning was for lots of wind. N20, moving SW and increasing to 30+. The dog and I discussed our options and motored out over the sand at first light, at the top of the tide, and headed up the Coles Channel to St Leonards, anchoring for some breakfast, waiting for the change. Sure enough by 0800 the squally south westerly came through, so we unfurled a few feet of headsail, pulled up the anchor and tore off across the bay leaving the imagined treasure behind, but with a few new treasured memories to take into the weeks ahead.