The Spice of Life

By Sal Balharrie

A rock art site in the southeast of Groote Eylandt depicting a Makassan prau.

(Credit :Anindilyakwa Land Council)

There was the Spice Road, but what about the Spice Route?

Thanks to the campaigns of Alexander the Great, who pushed all the way to India, pepper and cinnamon were to be ‘discovered’ by European palettes and once sprinkled across the great kitchen of Europe, like all great global innovations, demand took hold and there was no turning back. You could say, spices have been a mainstay of trade for a very long time.

What’s not to love about spice?

During the tenth century, the spice trade was in Arab hands. At that time, spices were brought only by land to Europe, travelling through Arab territory. Over land the goods migrated from middleman to middleman and by the time cinnamon arrived on a countertop in Paris, it was often one hundred times more than its original price.

The discovery of a Spice Route operated by sea would drive a revolution of commerce with the potential for water traffic to thread its way around the world from great port to great port. If a sea route could be found connecting the countries where pepper, nutmeg and saffron grew, Europeans could bypass the middlemen and customs and make insane profits.

Such considerations led the Portuguese to send off an expedition. In July 1497, the nobleman Vasco Gama set out to find a way around the spice road.

Da Gama sailed from Lisbon to the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, using a sea route that had already been developed by previous Portuguese navigators, he travelled along the east coast of Africa along the Arabian Sea to the West Indies.

Da Gama sailed around India and Ceylon and reached the Bay of Bengal and the Straits of Malacca, the Sunda and Banda and finally, the Spice Islands.

When Da Gama docked at the Indian Malabar Coast in May 1498, he and his men were the first Europeans to have ever travelled so far. Da Gama formed trade agreements in India and arrived back in Lisbon with fully loaded ships in July 1499.

Within a few decades, half of the Asian spice trade shifted from road to sea, giving the sea route its name: The Spice Route.

As thanks for his work Da Gama was appointed to the royal court, raised to nobility and finally appointed Viceroy of India. His journey laid the foundation for the 1506 -1570 monopolisation of the spice market by the Portuguese.

And so when did Asian spices first step off the Spice Route, make their way to Australia and into Bush Tucker?

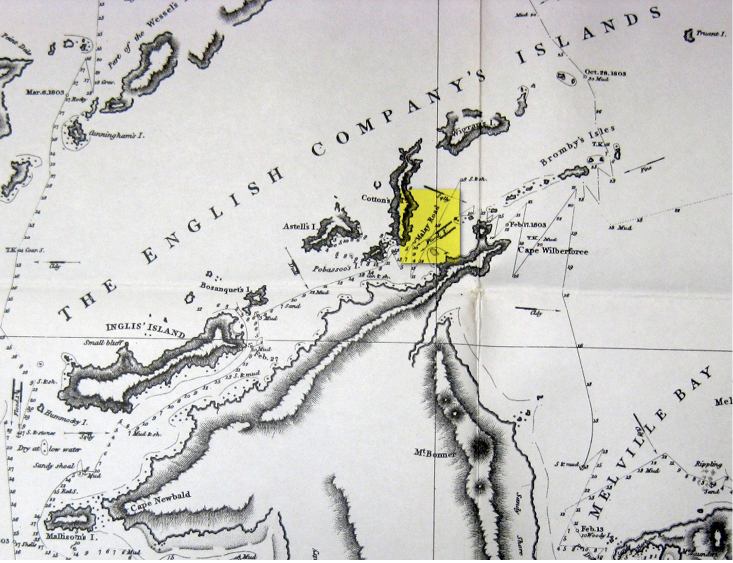

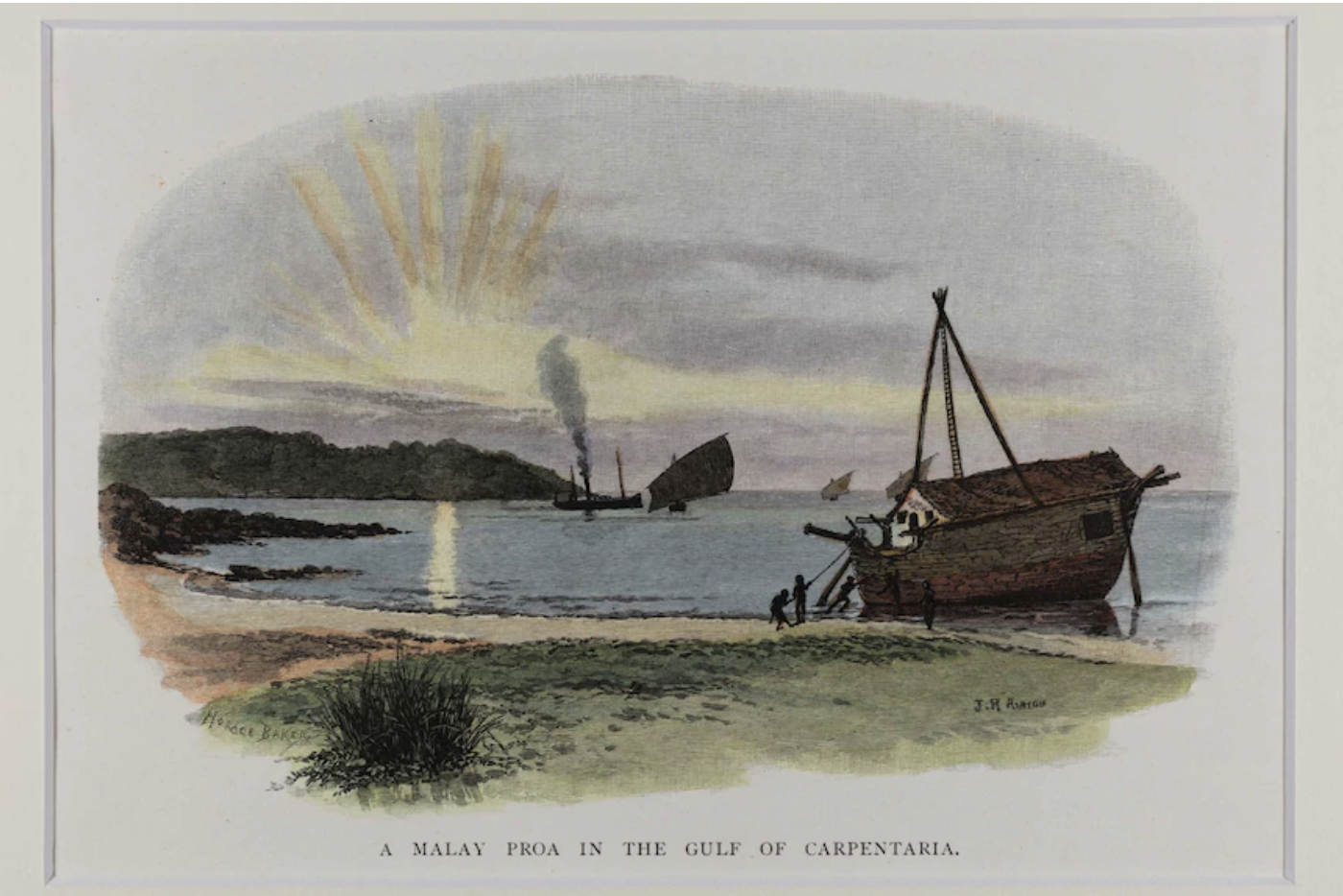

‘View of Malay Road from Pobassoo’s Island’. Painting by W. Westall, artist on Matthew Flinders’ Voyage to Terra Australis, 1803. Engraved by Samuel Middiman. Location is The English Company Islands, Northern Territory.

Source: National Library of Australia, PIC 52269 LOC Westall Box 16

Curious Darwin set out to answer the question - Did Aborginal people and Asian people trade before European Settlement?

Enter the Macassans and what

Mathew Flinders called, the Malay Road.

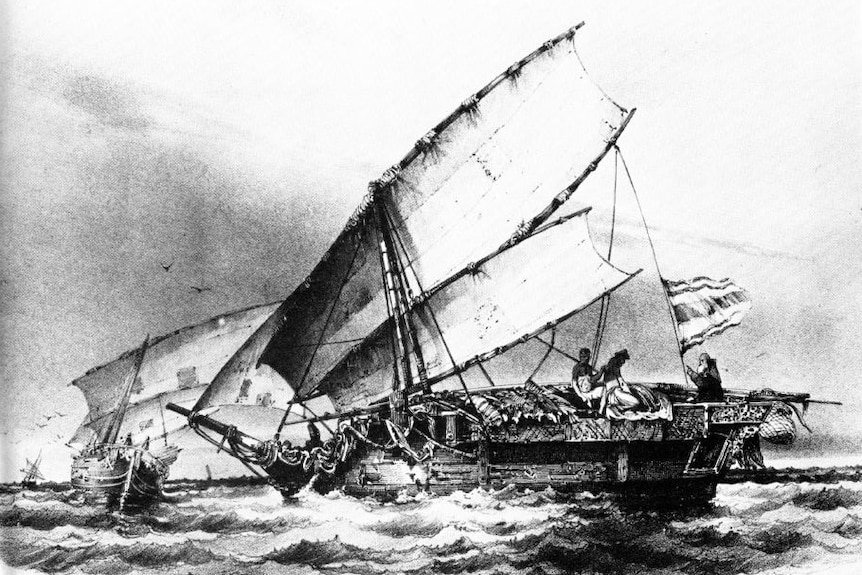

The ‘Malay Road’, just off the north-eastern tip of Arnhem Land, was part of the historical route followed by annual fleets from the port of Makassar in what is now South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The fleets sailed to the northern Australian coastline, seeking edible trepang or sea cucumber.

On Thursday, 17 February 1803, as he rounded Cape Wilberforce, having completed the survey of the Gulf of Carpentaria, the navigator Matthew Flinders recorded in his journal an encounter with six praus and their captain:

The chief of the six prows was a short, elderly man named ‘Pobassoo’; he said there were upon the coast, in different divisions, sixty prows, and that ‘Salloo’ was the commander in chief. These people were Mahometans…

[Friday, 18 February]…[F]ive other prows steered into the road from the S.W. anchoring near the former six…At daylight they got under sail and steered through the narrow passage between Cape Wilberforce and Bromby’s Isles, and afterwards directed their course south-eastward into the Gulph of Carpentaria.

[Saturday, 19 February]…According to Pobassoo, sixty prows belonging to the Rajah of Boni and carrying a thousand men, had left Macassar with the north-west monsoon, two months before…The object of their expedition was a certain marine animal called ‘trepang’…Pobassoo had made six or seven voyages from Macassar to this coast, within the preceding twenty years, and he was one of the first who came…

This road was the first rendezvous for his division, to take in water previously to going into the Gulph…Pobassoo even stopped one day longer at my desire, than he had intended, for the north-west monsoon, he said, would not blow quite a month longer and he was rather late.

The location of Flinders’ ‘Malay Road’

Source: After McIntosh (2006); based on Flinders’ chart ‘North West Side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, 1803’, in Flinders (1814, Atlas)

Impressed by the large number of praus he met at the rendezvous point for the trepang fleet, which was a sheltered stretch of water near the Wessel and English Company’s Islands just off the northeastern tip of Arnhem Land, Flinders named it in his journal the ‘Malay Road’. The ship’s artist, William Westall, has depicted the fleet of praus anchored in the Malay Road, as viewed from Pobassoo’s Island.

The route of the trepang trade from Makassar north to China and south to Australia.

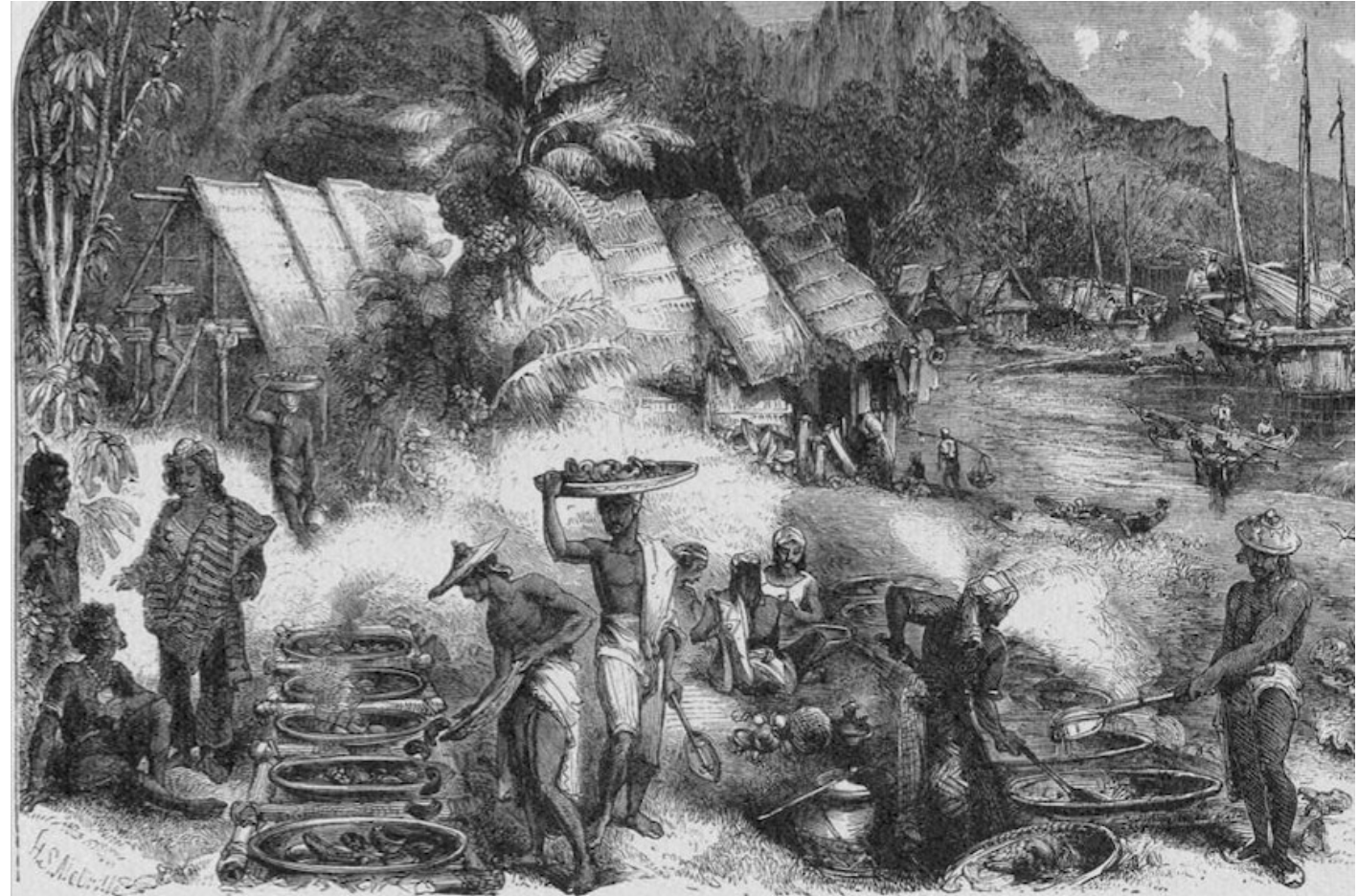

The Macassans came on yearly return visits, setting up temporary villages and processing sites at sheltered beaches along the coast. The Arnhem Land coast offered a long series of suitable anchorages, running parallel, or nearly so, with the direction of the monsoons.

The trepang industry in Australian waters was comparatively large and well organised. At the height of the trade, as many as 60 praus carrying between 1000 and 2000 Macassans spent four to five months of the year gathering trepang. The product fetched considerable amounts of money in Makassar for the fleet financiers, who enjoyed high social standing in their community. Shipping to southern China was handled by the Chinese businessmen living in Makassar. Most voyages were financed and outfitted by merchants who supplied basic items like rice, tamarind fruit, ‘kajang’ (awning mats made from palm leaves), ‘atap’ (mats similar to kajang, made of nipa palm leaves), rattan, ‘karoro’ (palm-leaf sail cloth), iron pots for cooking, ‘parring’ bamboos for building, and so on. At the height of the trade from the 1770s, an annual junk sailed directly from Xiamen, or Amoy, in southeast China, to Makassar to collect the trepang.

Can I draw your attention to that a rather incredible statement – between 1000 and 2000 Macassans spending four to five months at a time gathering sea cucumber.

And what did they bring with them? Of course items to trade such as axes and metal implements, fabric and boat design. But what they did share, impart and leave behind was spice in the form of BLANCHAN, here it is from the ABC.

The underground world of blachan

in the Northern Territory where recipes

are top secret

A drive out of Darwin and into the heart of the city's suburbia, a peculiar smell drifts out of a home and it's drawing in the flies.

"It's like a real dead fishy smell," said Mark Motlop, who cooks the spicy condiment, blachan, from his home in Wulagi. "But as you start to cook it and add all the ingredients, you get a sweet smell and it turns into something that you get used to," he said.

Loaded with a mix of fresh chilli, ginger, garlic, onion and shrimp paste, blachan is a popular relish across Australia's far north. How it tastes is either loved or loathed, and getting your hands on a jar usually comes down to local connections.

"If we have a barbecue, the blachan is always on the table," Mr Motlop said. "If you go to a wedding in Darwin, there'll be blachan there, someone will sneak it in. If you haven't had blachan, you haven't been to Darwin. It's just everywhere here and people will ask for it," he said.

Spices, family and 'that stench' Mr Motlop grew up watching his father Edward, who moved to Darwin from the Torres Strait Islands in the 1950s, make the spicy sauce. His father made "the real deal", he said, using fresh shrimp paste, known as hama, sourced from a Chinese grocer well before the packaged varieties came to town.

However, Mr Motlop couldn't stay in the kitchen for long to watch his father make it because of the stench that would rip through the house. “Even the neighbours would say 'what's that smell?' and you would see them poking their head out and thinking 'what's going on over there?'"

The story of the travelling recipe

When he turned 18, Mr Motlop left Darwin to play Australian rules football with the South Australian Football League. There was no blachan to be found in Adelaide, so he was forced to learn the recipe over expensive long-distance phone calls to his father back home.

"I continued making it and just tried to make it as good as my dad did," the 63-year-old said. After playing football in leagues across the country, Mr Motlop came back to Darwin and played 269 games with the Nightcliff Football Club – where his family name reigns. He then spent the next 30 years of his life coaching most football clubs in Darwin and said blachan was key to his success as a coach. "When I was coaching Buffs (Buffaloes), the payment that I used to pay a player to come up was two jars of blachan …it's quite a delicacy for people."

Tracing the history of blachan

In Indonesia, the spicy shrimp sauce is known as sambal belacan and throughout South East Asia, the delicacy goes by many different names. Growing up, Mr Motlop thought the sauce was "just a Torres Strait Islander thing" until he noticed his Indigenous family on his mother's side were making it too.

It led him to think about Makassan seafarers, who fished for trepang in northern Australia and traded with Aboriginal people along the Arnhem coast in the 18th century.

"The Makassans were definitely part of that trade … they had a big part to do with blachan coming to Australia," Mr Motlop said. "While I'm cooking, I think about the Makassans, their travels, how blachan got to the Torres Strait, how it got to the tip of north Queensland, how it got to Darwin, how it got to Broome and even how it's got down to Alice Springs now."

Communities unite over love for chilli sauce

Hidden at the back of an inner-city arcade, Nurainiah Majid starts her week by making a fresh batch of sambal belacan for customers at her Indonesian restaurant. Three kilograms of fresh chillies, bought at the local market, are first to go in the blender with onion, tomato and a block of packaged shrimp paste, that resembles a soap bar. Unlike Mr Motlop's method of simmering everything in a pot, Ms Majid fries her mix in a wok until the chillies change colour and the flavour is locked in.

"I put the fire on and cook it with a bit of oil, salt and sugar, that's it … but you have to be careful not to burn it," she said. It's a recipe the 46-year-old learnt from her mother back home in Surabaya in East Java, and brought it with her to Australia, when she immigrated with her husband in 1997. When she opened her restaurant, The Sari Rasa, in Darwin 20 years ago, Ms Majid said she couldn't believe it when

Territorians were asking for blachan – the phonetic way of saying shrimp paste in Bahasa. The mother of five regularly gets customers from Arnhem Land popping into her store for the relish and said it's all they want from the bain-marie.

"I didn't think the Aboriginal people knew about belacan but my husband explained the history of the people from Makassar coming here and mixing with Aboriginal people and they know about Indonesian food too," she said.

The secretive side of blachan

Nurainiah Majid said there are no secrets to her recipe and she's happy to share it with people who ask. But Mr Motlop said it's not the same in his circles, where Darwin's blachan makers are fiercely guarded about what they put Mr Motlop is fairly open about his ingredients - except for one, which he adds to the pot at the very end.

“A good chef never gives away his full recipe … so that's the one thing that I don't let you know what I put in," he said.

As for who can claim ownership to the relish in Australia? Mr Motlop said he'd have to "build a 20-foot fence with barbed wire" if he said Darwin owned it over Cairns and Broome and said the sauce has come to represent the way of life, up north.

"It belongs to the people, everyone has their own way of making it … it's just part of the multicultural side of Darwin and the Top End of Australia. People from all walks of life will want it, whether you're Indigenous or not, or from another country … you'll have a taste and you'll want more."