You know about Dunkirk of course

By Malcolm Lambe (our regular and sometime European correspondent)

To begin, I’m a wooden boat tragic. I have absolutely no interest in fibreglass boats no matter how pretty they look or how well they perform. Something about timber turns my crank. So when an ad popped up on Facebook – they stalk me and dangle timber vessels under my eyes - for an eighty foot 1939 John Bain designed classic motor yacht on the hard in the South of France and “awaiting restoration” I was immediately interested. My interest ratcheted up a notch when I discovered it was the Dunkirk Little Ship CONIDAW – renamed THOMASINE

You know about Dunkirk of course. Surprisingly my French wife didn’t – even though her Grandfather was a Resistant (Légion d’honneur First Class) and with De Gaulle in London during the war. But there again the evacuation was mainly to get British soldiers to safety across The Channel. But there were 140,000 French and Belgian troops along with the 198,000 British saved during those ten days from 26th May to the 4th of June 1940. Yes mate – by the time you read this it will be the 83rd anniversary of those fateful days. And I’ll be in Dunkirk to witness it. It’s only a three hour fang up the Motorway from my house in a Paris suburb.

HMY CONIDAW played a heroic part – both at the Seige of Calais and at Dunkirk. But first..some background. Some of this I’ve taken directly from https://www.adls.org.uk/ the website of The Association of Dunkirk Little Ships. A very interesting site.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) moved into France in September 1939.

During the next eight months, nicknamed “The Phoney War”, the Brits spent most of their time digging field defences – and moaning no doubt. I’ll take that back. Cheap shot. “Don’t mention the war. I did once but I think I got away with it”.

The fun and games ended with the invasion of France and the Low Countries by the Nazis.

Germany attacked in the west on May 10th, 1940. British and French commanders believed that German forces would attack through central Belgium as they had in World War I, and rushed forces to the Franco-Belgian border to meet the German attack.

However the main German attack – the Blitzkreig - went through the Ardennes Forest in south-eastern Belgium and northern Luxembourg. German tanks and infantry quickly broke through the French defensive lines, skirted the impenetrable Maginot Line and quickly advanced to the coast.

By May 1940 the allied situation was getting desperate. The German Panzer divisions had reached the outskirts of Calais and only a handful of riflemen were left to defend the town. The battle was unwinnable and after a devastating pounding, the garrison was ready to leave. But if Calais fell there was nothing to stop the Nazis driving through and massacring the remnants of the French army and the British Expeditionary Force trapped on the beaches at Dunkirk – a short distance North of Calais – forty-something kilometres. Winston Churchill said it was the toughest command he ever had to give but on the 25th of May he issued this order:

“Every hour you continue to exist is of the greatest help to the BEF. Government has therefore decided you must continue to fight. Have greatest possible admiration for your splendid stand. Evacuation will not (repeat not) take place, and craft required for above purpose are to return to Dover….”

Churchill wrote later, “One has to eat and drink in war, but I could not help feeling physically sick as we afterwards sat silently at the table.” As he did so, the defenders clung grimly to their positions, fighting until the following evening when their heroic resistance finally petered out. If one episode might be said to have permitted the miracle of Dunkirk to succeed, then it is probably the defense of Calais.

But how did they get the signal to the beleaguered garrison in Calais? The soldiers had no working radios and the telephones were cut. The only possible solution was to send the written command by hand, so the vital message was entrusted to Royal Naval Reserve Lieutenant Reginald G. Snelgrove, who took HMY CONIDAW under continuous bombardment through the minefields into Calais to deliver the order to Brigadier Nicholson in person.

Next day the fighting was frantic, and one after the other the remaining Allied ships left the port. Finally CONIDAW was the only one left, staying on alone while the ferocious battle raged around her. Only as the first tanks of the 10th Panzer Regiment burst onto the quay itself did the last 165 soldiers jump on board and CONIDAW left Calais as fast as the twin Gardner 6L3s could drive her.

But just on clearing the mole, disaster struck. She ran aground. The cramped soldiers must have felt they faced death in a few minutes. Nazi artillery would show no mercy for a stationary target with nowhere to hide. But then a fortuitous near miss by a bomb blasted the yacht off the sand with its shockwave and she scurried away to Dover. The scars of that encounter are still with her as her port engine still has a repaired cracked sump from that bomb blast.

Lieutenant Snelgrove received the Distinguished Service Cross in recognition of his heroism in Calais that day. His signalman, T.H. Bailey, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Next morning CONIDAW joined the armada of little ships rescuing the remaining French and British soldiers off the Dunkirk beaches. Her shallow draft allowed her to go close inshore to take the starving, frightened and exhausted men out to waiting ferries in deeper water. Altogether she saved 900 in this way before returning battered but unbowed to Dover with another 80 soldiers on board.

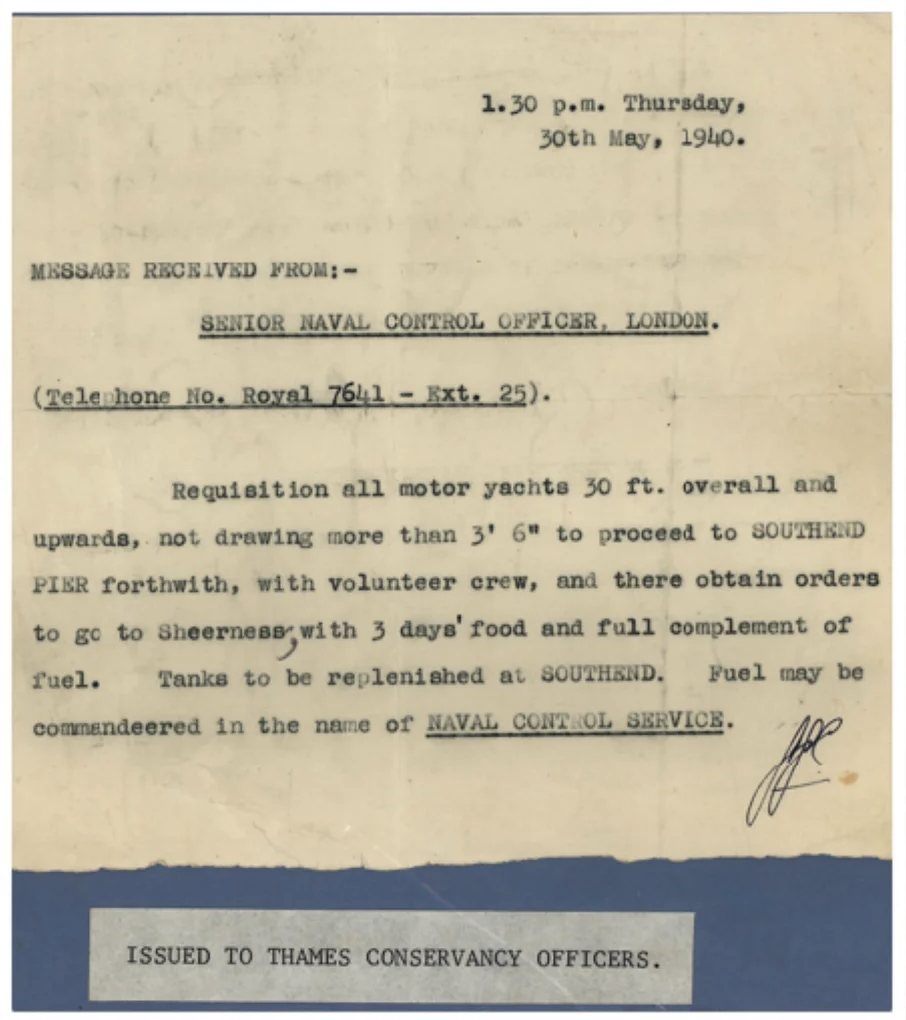

The first possibility of an evacuation was considered back in May 19th and given the code name Operation Dynamo. Vice-Admiral Ramsey maintained secrecy whilst scouring British docks for vessels to transport troops from French shores to waiting larger transporters. His order read –

“Requisition all motor yachts 30 ft overall and upwards, not drawing more than 3 foot 6 inches to proceed to Southend Pier forthwith, with volunteer crew, and there obtain orders to go to Sheerness with 3 days food and full complement of fuel. Tanks to be replenished at Southend. Fuel may be commandeered.”

Little Ships being towed down the Thames

By May 27th these vessels were consolidated and on their way to France. Approximately 850 private boats sailed from Ramsgate, over 250 were lost. Churchill and Admiral Ramsey hoped to rescue between 30,000 and 40,000 troops.

In the end the combined efforts of the RAF, the Royal Navy, the French Navy, the Polish Navy, the Belgian Navy and fishing fleet and the Little Ships rescued 338,000 troops.

But for every seven soldiers who escaped through Dunkirk, one man was left behind as a prisoner of war. The majority of these prisoners were sent on forced marches into Germany and Poland enduring brutal treatment by their guards, including beatings, starvation, and murder.

The rescue operation turned a military disaster into a story of heroism which served to raise the morale of the British.

The phrase "Dunkirk Spirit" is still used to describe courage and solidarity in the face of adversity.

So this little champion...this Dunkirk Little Ship - CONIDAW launched in 1939 - is on the hard in the South of France - at La Ciotat to the East of Cassis – crying out to be saved.

Originally the shipyard wanted €250K – AU$406,000. Bet you could throw another €500k or more on top to restore it properly. But now a nominal €1 and a drink for the broker will save her for posterity. Time is running out. A week ago the yard said the fees for the land the boat is standing on have increased five-fold to €2500 a month. So its unsustainable for them to keep her.

Personally I think King Charles and his wealthy chums should rattle the can and save this vessel.

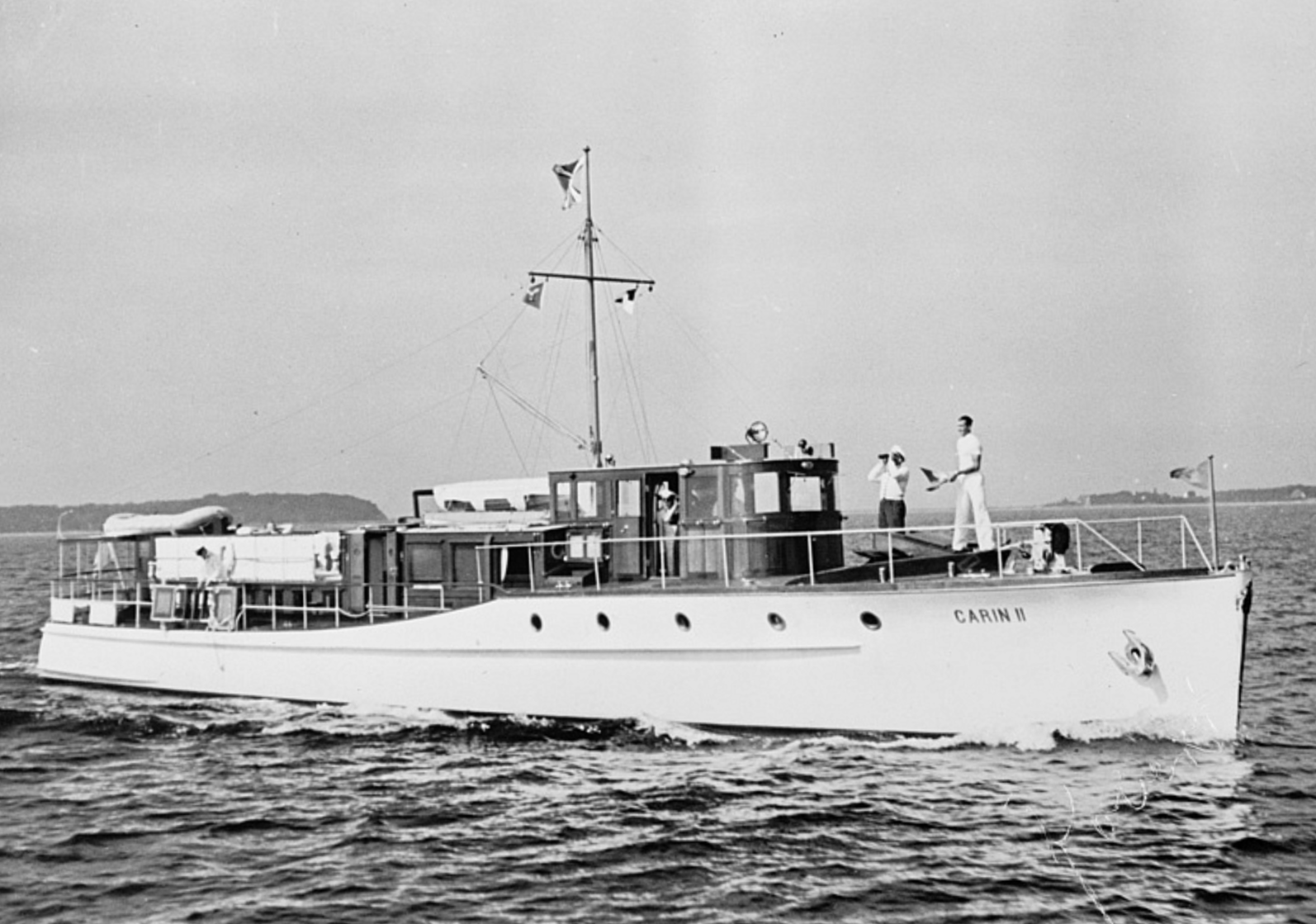

BTW nothing is impossible. I heard of a similar vessel of a similar age – 1937 - in a similar shitty state back in 2008 lying derelict in The Red Sea. I wrote about it extensively and sparked enough interest – in amongst heaps of Flak – to get the attention of a German businessman who saved and restored her. The boat? Hermann Goering’s 90 foot long CARIN II.

Double diagonal planked oak, laid teak decks, twin Mercedes-Benz diesels. Not seaworthy – the shafts had been deliberatedly cut during an ownership wrangle. But we saved her. Now called “Prince Charles” as it was requisitioned after the war and used as a V.I.P. boat in Germany. Prince Charles spent time aboard as a boy and was put to work peeling potatoes in the galley.