The Original, Centuries Old, Cargo Shipping Container

By Duncan Blair from his blog, Traditional Sail

I am offering this post as a kind of parable, an opinion piece, about old technologies, skills and materials connected with traditional sail that are still used and are still relevant in today’s world—no plastic, fiberglass, electricity or Velcro.

Consider the commonplace wooden barrel, made of individual parts called “staves”, each one shaped with a plane or a draw knife in order to fit tightly together, with interlocking top and bottom pieces, also made of wood. All of these parts are held together by metal hoops.

Before iron barrel hoops became available hoops were made from strips of green willow saplings, called “withies”that were split and hand-woven into hoops, first soaked in water, the pressed down on the outside of the barrels. As they dried they hardened and shrank, holding the staves tight against each other. Nature provided the oak wood for staves and the withies for hoops; the only other things needed were a good eye, strong hands and a sharp tool to shape the wood. When iron hoops became common a special hammer was added to this tool kit.

The term use to describe the making, assembling and repairing of barrels is “cooperage”. The person who does this skilled work is, therefore, called a “cooper.”

Coopers were in great demand during the centuries of working sail. They were skilled specialists, like gunners, ship wrights, caulkers, sail makers and riggers.

For centuries (the earliest records of barrel use date from 350 B.C.), barrels enabled the transport of a large variety of cargoes, for the simple reason that barrels were and still are, the perfect modular shipping container.

They sit flat and stable on the deck, their convex sides, called “bilge,” give protection from bumps and pressure. They can be stored upright in cargo holds and still have air circulating around their curved sides. They can also be made from varieties of a widely available and sustainable material called “wood”.

The barrel’s modern version, the steel oil drum, sometimes known as “the state flower of Alaska”, can also be useful in some circumstances, but lacks the esthetic, sustainability and grace of its ancestor.

Over the centuries barrels have been used to store and transport all sorts of cargo; gunpowder, paint, salted meat and fish, hardtack, nails, honey and tallow. All of these things are in the category of “keeping the liquid, such as water, out”. In the category of “keeping the liquid in” there were and continue to be, things like wine, whiskey, water, tequila, balsamic vinegar and oil—especially whale oil.

Oil extracted from the blubber of whales, done on board the whaling ship using brick furnaces built on deck to heat the blubber in iron cauldrons, was stored in wooden barrels. Most of the barrels had been disassembled and carried below decks in bundles of staves and hoops until they were needed, then they would be assembled by the ship’s cooper and his assistants. Oil and especially whale oil, which was a high dollar commodity in the first half of the 19th century and was commonly used in homes and street lamps in the NE United States and Great Britain, was especially difficult to keep contained, even in wooden barrels. As a result, “oil coopers” were considered to be the most skillful of all coopers.

SPINNING—ROLLING—PARBUCKLING

When barrels needed to be moved across a warehouse floor or the deck of a ship they were laid down on their curved sides. This curved, convex surface, intentionally built into the barrel, made it easy for one person to direct and control the movement of the barrel, using the curved surface to turn the barrel right or left or even to spin them, and by doing so, stop them in place.

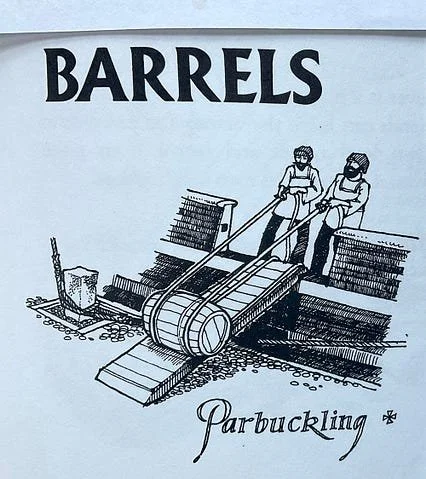

The most sophisticated and interesting barrel transport maneuver is call Parbuckling. To understand and appreciate the ingenuity of Parbuckling you first need to understand the Physics behind it. It should be no surprise to learn that this knowledge, in vernacular, pragmatic form, has also been known for centuries.

So first some technical background and pictures.

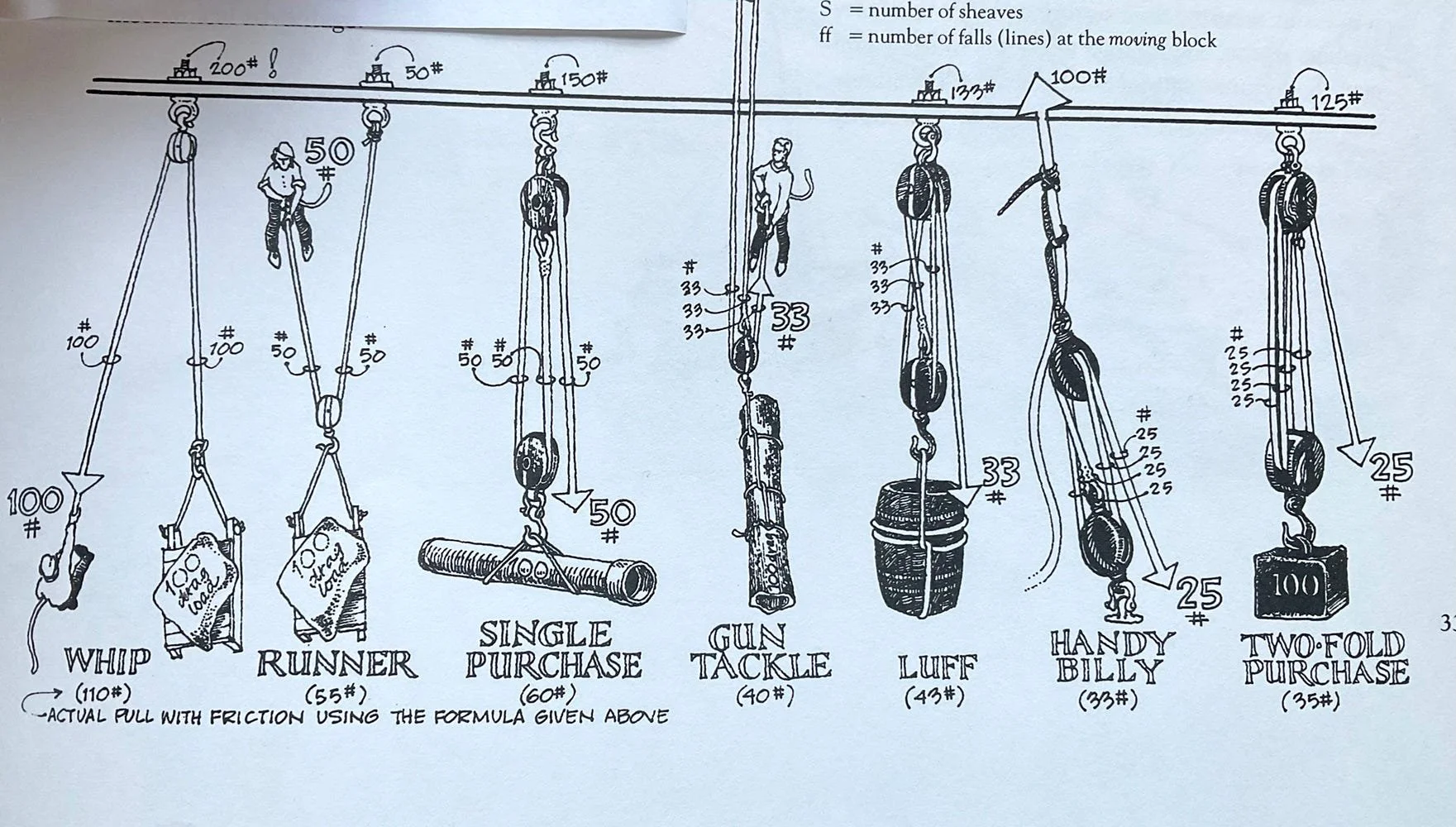

The Block and Tackle—one form of this basic and universally known tool is the Handy Billy, which is just a block and tackle that is small enough to be easily stored so as to be available for any number of uses. The blocks use have attachment points, called Beckets allowing connection to whatever needs to be moved or tightened. The Handy Billy can be understood as the precursor to the modern Come Along, which uses cables instead of rope, ratchet drums in place of blocks and has a lever (Archimedes would be proud) to help really put the mash on whatever the Come Along is doing.

Block and Tackles are still used, as they have been for centuries, to multiply the force applied by human hands. Their specific use in the category of traditional sail was and is, to lift heavy loads and/or to tighten cables and ropes; think about halyards/halliards/ originally called HAUL YARDS—the ropes used to raise and lower heavy sails and yards. Handy Billys used to tighten the luffs of lug sails and gaff sails are generally known as “down hauls”. Heavy duty tackles were permanently installed to secure heavy anchors outboard of the bows, to be “catted and fished”, safely secured and ready to be used again.

To accomplish this work blocks are built with parallel cheeks connected by a strong through pin. Between each pair of cheeks is a disc with a groove cut around its circumference, the width and depth of the groove conforming to the diameter of the rope that is used.

Block with iron shell and hook. Note that this block does not have cheeks; the iron shell holds the pin.

Modern wood double block with bronze sheaves sized for 1/2” rope

The disc—known to lubbers as a “pulley”, is actually a “sheave”, pronounced “shiv” by any two-fisted, tattooed sailor man, or woman.

The shiv turns freely on the pin as it passes through the block, guided and supported by the pin.

This combination of rope, block and rolling shiv reduces the “felt weight” of the load, giving what is known as “Mechanical Advantage”. In more complex tackles the number of lines moving through the blocks on the shivs indicates the amount of Mechanical Advantage.

PARBUCKLING

The technique of Parbuckling has been around for a very long time, known to sailors who never went to school, never studied Physics and who could not write, let alone spell the words Science, Technology, Engineering or Mathematics (STEM). They did, however, have the common sense and ingenuity of people who work for a living, especially those who work with the muscles of their backs, arms and hands.

Parbuckling cleverly uses the cylindrical body of a barrel or pipe or straight tree trunk in place of the shiv in a block-doing the same thing that a shiv does; creating mechanical advantage, but without the cheeks and pin of block.

The barrel being lifted IS the shiv.

Using another Archimedean device(the first mentioned above was the lever) known as the Inclined Plane, Parbuckling requires only a long piece of rope, doubled at one end, the other two ends securely belayed on strong points.

The illustration shows two stout lads pulling together to get a barrel weighing at least 400 pounds (barrel’s volume of 53 gallons multiplied by the weight of I gallon of water-8.35 pounds = approx. 445 pounds, not including the weight of the barrel itself), up an inclined plane/ramp and onto the deck of a ship.

DOWN THE BOOZER

Barrels have always been associated with the storage and shipping of alcohol. On the American frontier of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and especially East of the Mississippi River, early settlers often grew corn for food, forage and as a cash crop. The best way to preserve the harvested corn was to make corn mash and distill it into alcohol. This added value, made it much easier to preserve—in barrels and made it easier to send to market, down river—in barrels.

Wood of all types has compounds called vanillin and tannin in its fibers and these compounds impart flavor and color tones to the whiskey stored in the barrels. Today many whiskey barrels are deliberately charred, carefully burned with fire on the inside to increase and enhance the unique flavor and color tones coming from the wood.

Barrels are also used to mature Sherry and Port wines, with the wine being kept in the barrels for several years before it is bottled and exported for sale.

The wine barrels used to age the wines are often recycled by being sold to whiskey distillers to add more subtle flavor tones coming from the wine soaked wood of the barrels.

So the next time you take your wife down the Boozer, meaning to the Pub, explains to her how it is that your dram of whiskey and her glass of “oaked” Chardonnay might have come from the same barrel. She is bound to be impressed by your knowledge.

WHAT DOES ALL OF THIS TELL US—IF ANYTHING ?

The point of this parable is simply that traditional technologies (sheaves), materials (wood and rope) and tools (handy bills, inclined planes and levers) are still with us and are still being used—because they work!

They are simple, straight-forward and easily understood, unlike many electronic devices, and, best of all, they do not require the use of a Password.

While there not as many coopers, sailmakers, shipwrights, block makers, caulkers and blacksmiths as there once were, all of these trades and knowledge still exist and are still being employed.

So ask yourself a What If Question.

What if your shiny, new electric anchor winch suddenly stopped working, after you dropped anchor and now want to raise the anchor and sail away? What would you do?

Maybe improvise a handy billy with a four-part purchase, attach one end of it down low on the main mast—or fore mast—and attach the other end to the anchor rode or chain, then set up the backstay(s) to help carry the load, then carefully, slowly haul away—maybe sitting down on the deck, facing forward with your feet braced against the offending anchor winch so you could use your feet, back and legs to pull.

Of course, you could just cut the rode with a sharp knife and abandon the anchor, always assuming that you were not going to need it again anytime soon. This would be an example of the Law Of Unforeseen Circumstances that all of us have experienced.

Maybe the final lesson is to have some knowledge of tried and true traditional methods and tools that you can fall back on when—and if—the shiny, new tech stuff doesn’t work.

This approach is currently known as the KISS Principle.

PAU

As always, all ideas and opinions expressed above are mine alone.

DUNCAN BLAIR