What an Arduous Business!

A review of Ben Pester’s book Just Sea & Sky by Annie Hill

When I read the old sailing books, I enjoy the different perspectives authors bring to the art of navigation by sextant. In the days before satnav and then GPS, all voyagers had to have at least a passing acquaintance with the sextant. The more cavalier only learnt how to take a sight for latitude, known as a ‛noon sight’ and having arrived at the latitude of their destination sailed east or west until such time as they found it. This method relied on having a really good Dead Reckoning position and the slightly less cavalier of its proponents would normally choose to make landfall somewhere that had a bright lighthouse nearby. The 12-hour nights of the Tropics makes any uncertainty as to how close you are to land, much more of a worry than in higher latitudes. That being so, most sailors learned how to take sights for longitude, which were somewhat more complex to work out and also required an accurate timepiece. Ironically, of course, the marvel of quartz crystal arrived only a short time before satnav, so that most sextant sailors on small boats tried to get some sort of time signal as often as possible. The sort of radio most could afford meant that this was a bit hit and miss, so they ‛rated’ their clock, watch or (if they were a bit less impecunious) chronometer. If the timepiece gained or lost regularly, the navigator was perfectly content. Five seconds a day was considered good, half a minute made the sums even more difficult!

The greatest advantage of having to navigate by sextant, in retrospect, is that it put many, many people off the idea of crossing an ocean. There was a bit more elbow room in harbours around the world before the advent of satnav. However, of course, these voyagers never dreamt of such a thing as being able to press a switch and instantly see your position to the nearest few metres, so their attitude to taking a sight was different from what a modern sailor’s would be. What is interesting about Just Sea & Sky, is that it was published in 2009, but written about a voyage commenced in 1953. Ben Pester writes obviously with hindsight and this gives a different character to the account. A few years before writing this book, Ben and two friends (total age 193 years!) had made a very adventurous voyage from Falmouth (England) to Cape Horn and back (Through the Land of Fire); on this voyage he had made use of GPS, so his awareness of the difference between that of 1953 and the one of 1999 is enhanced.

Eric and Susan Hiscock had started their first circumnavigation in Wanderer III, the previous year, and to those of us who have read (and re-read!) Around the World in ‛Wanderer III’, another interest of the book is the difference in attitude between Ben and Eric. Ben, at the time of his voyage, was a young officer in the Royal Navy and was about 20 years younger than Eric Hiscock. Even though the book is written in retrospect, Ben comes across as a young man and Eric as more mature and considered.

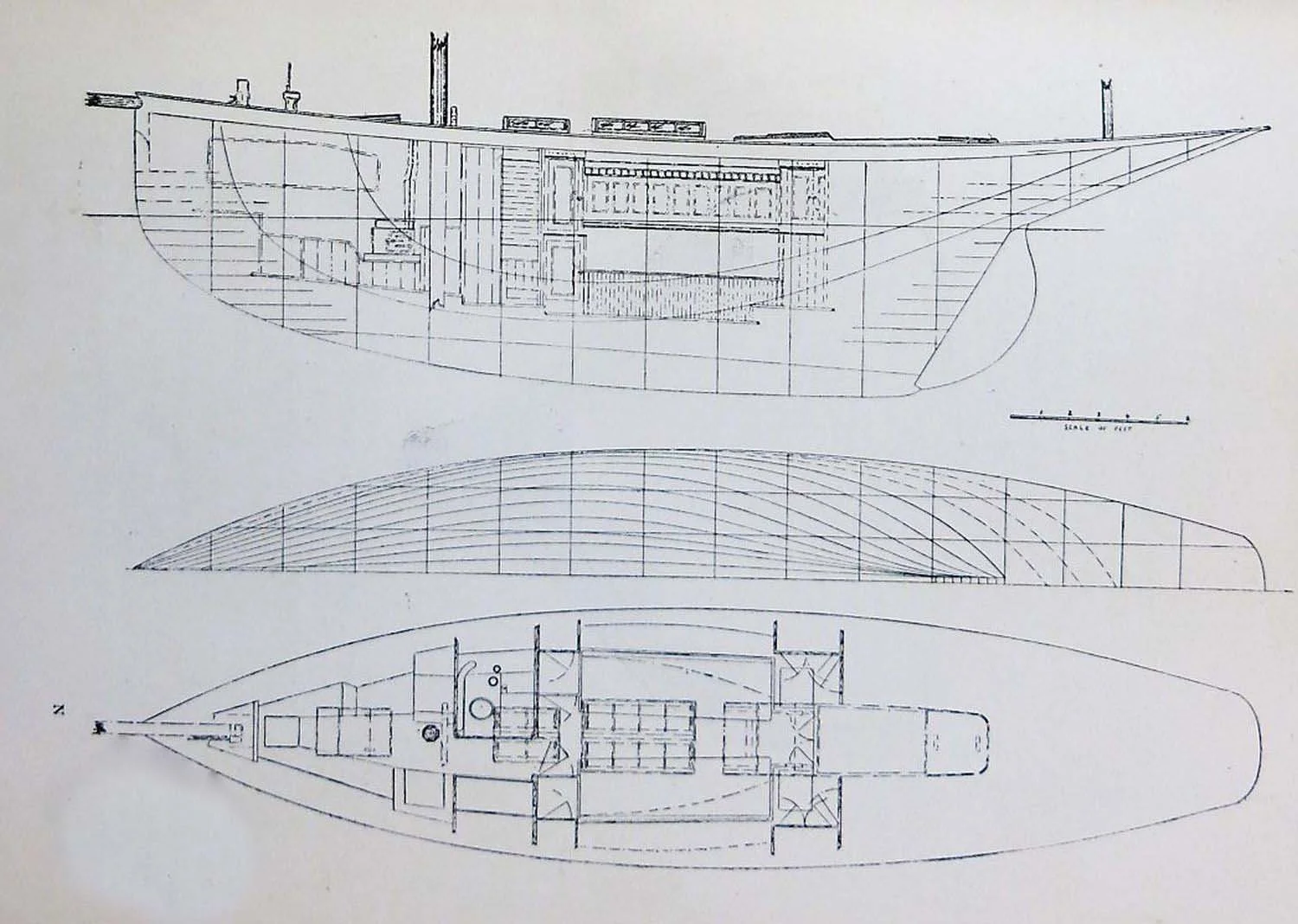

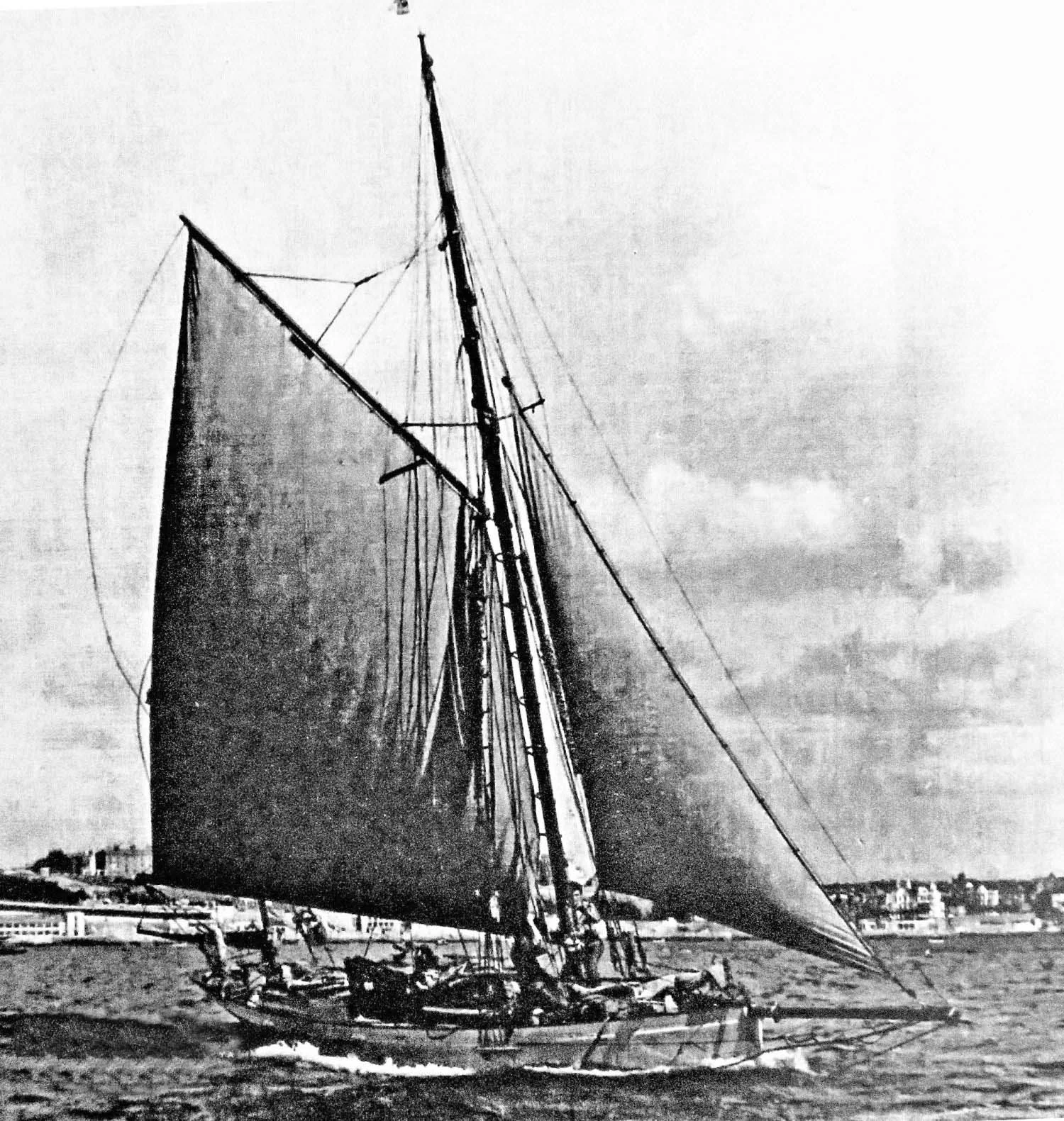

For cruising history buffs, an additional point of interest is that the boat that they sailed out to New Zealand was none other than Claud Worth’s Tern II (and, incidentally, she is still in New Zealand being slowly rebuilt).

However, for me, it wasn’t only the difference in navigation methods between the 50s and today that were of interest, but also the work entailed in sailing a gaff yawl compared to that of a modern rig (let alone a junk!).

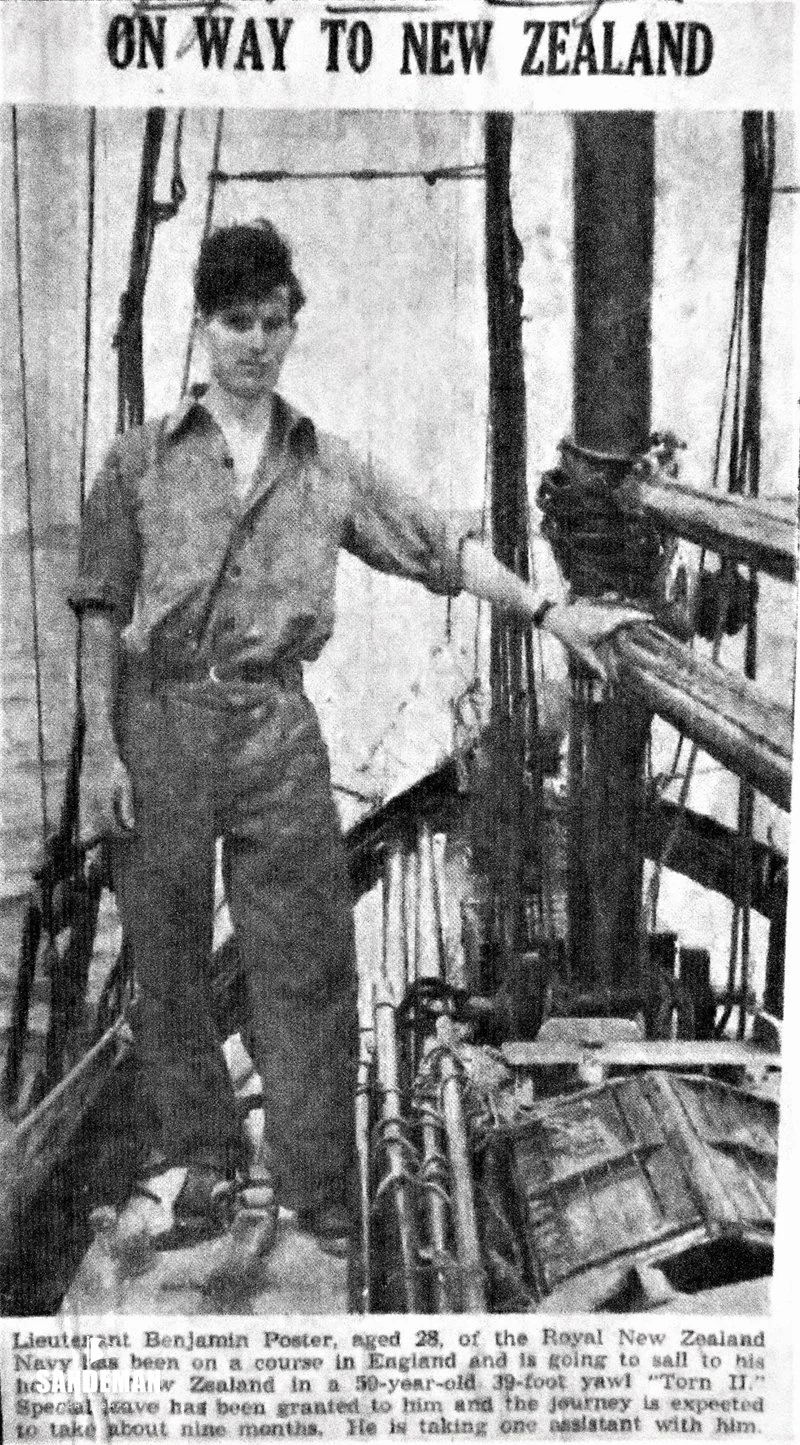

Back in 1952, when Ben started planning this voyage, the Royal Navy hadn’t really got into ‛adventure training’ (I imagine that most of the older officers had experienced more than enough adventure, in the previous decade), so it was a lucky chance for Ben, that the Lords of the Admiralty decided that he should be posted to New Zealand (which also happened to be the country of his birth). The plan had been for him to get there by ship, as was the norm in the 50s, but Ben, who as a boy, had read all the accounts of small boat voyages written up to that time, thought this was the ideal opportunity for him to undertake that long ocean passage of which he had dreamed. He was lucky that both the naval authorities in New Zealand and those in England were sympathetic to his plans, so much so that he was leant a chronometer watch to help him with his navigation (lucky man!). The only drawback to the arrangement, was that he would be on unpaid leave; however, he was given the cost of the steamer fare, which was greatly appreciated as the cost of fitting out his boat would have probably meant asking for a bank loan – which may well have been refused.

He advertised for crew and was swamped with letters. Many people wanted to get away from the drab and bankrupt country that Britain was after World War II. More than a few women applied, but the fact that a ‛mixed crew’ would have caused many pursed lips, and the fact that Ben himself was ambivalent about the idea, made him decide to take another man. After corresponding with a great number of people, and interviewing half a dozen or so, he settled on Peter Fox. He makes the wonderful comment: that he ‛was single and hence had no family commitments’. These days, many people put off going voyaging because of their parents; I suppose it wasn’t that long previously that sons had been conscripted off to war. No doubt, once a young man had ‛flown the nest’, his parents expected him to get on with his life on his own terms. It still wasn’t the norm for a house to have a telephone and not everyone enjoys writing letters.

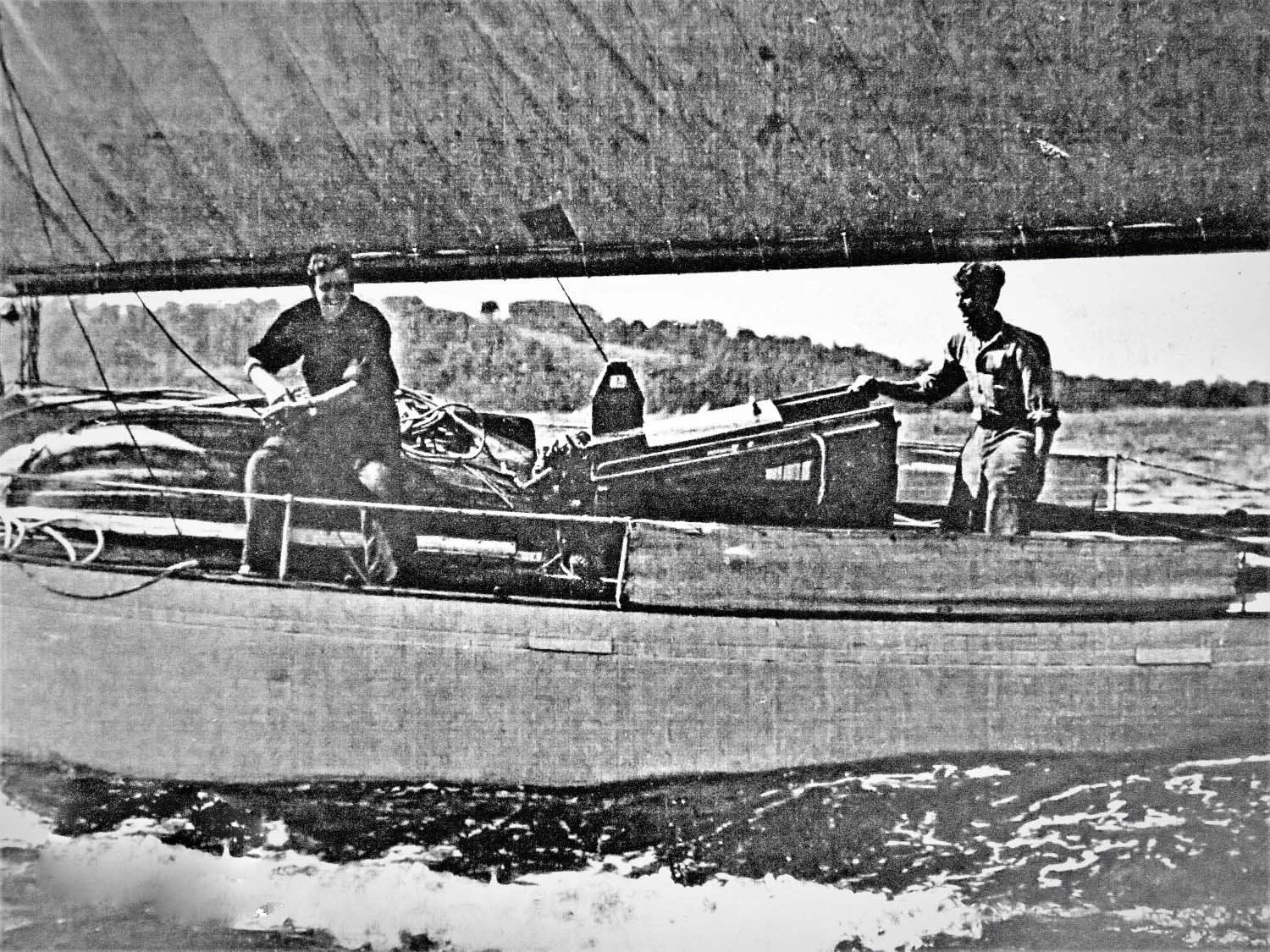

With the matter of crew settled, Ben set about preparing Tern for her voyage, generously assisted by the Navy’s resources. He reflects that these days, ‛there would be accusations of misuse of government resources’, but feels that there was much more give and take when he was a young man. Those who served, willingly put the Navy’s needs first, but in turn expected ‛The Service’ to look after them. He learnt to use his sextant – a beautiful instrument that had been ‛liberated’ from the Germans – and like many sailors, came to find deep satisfaction in the practice. Finally, on 30th August 1953, they set sail and left Plymouth bound for New Zealand.

What an arduous business it is, sailing a gaffer! They had gone closer to Ushant than was prudent. This was a time before traffic separation zones, and while it would undoubtedly have been better to stand on another 20 or 30 miles into the Atlantic, like most of us, they couldn't resist turning the corner. Nor of course could all the other ships, and they found themselves closer in than they’d have chosen in a lumpy sea, made worse by strong tidal streams. The boat was pitching terrifically and at one point the whole bowsprit was submerged. The strain proved too much and the joining link in the bobstay chain, carried away. Ben managed to rig a purchase to save the bowsprit, and they decided to put in to Brest to repair it properly. It was, of course, dark and, not having a large-scale chart, they hove to until daylight. The wind had now died away and shifted: once they had made sail again, they were running. The sheet from the swinging boom caught under the starboard lifebuoy and knocked it into the sea. ‟Rigged boom guy. Must always do this in future on all points of sailing except when close on the wind. That boom is lethal.” The joys of gaff rig! And yet, Ben remarks on how easy Tern II is to sail compared with earlier cruising boats such as those sailed by Richard McMullen. Tern II had also carried away her topsail sheet, soon after leaving Plymouth. They had lowered the mainsail and then rove a new one, with the gaff actually on deck. Ben compares this with McMullen, who would have shinned up the mast and then gone out along the gaff to re-reeve the sheet, with the mainsail still drawing! He notes, too, that while dealing with his bobstay failure, he had to crawl out along the bowsprit with nothing to hang onto while hooking on the new tackle. This, along with having to change headsails in deteriorating weather, put Ben off bowsprits for life – Marella, in which he sailed down to Cape Horn, had all her sails inboard. Again he contrasts his (perfectly understandable) trepidation with McMullen, who regularly reefed his bowsprit when shortening sail and also used to house his topmast, it being considered ‟unseamanlike to sail about with two or more reefs down and the topmast still aloft”. No doubt, but as Ben rightly observes, ‛the heart quails’ at the thought of striking the topmast: the signal halyards, topmast stay, topmast shrouds and backstays must be eased up – and that’s just the start of the operation! The Victorians were a hardy breed of sailor.

After a brief stop in Brest to repair the bobstay properly, Tern II carried on towards the Canary Is, but once again made an unscheduled stop, this time in Lisbon. They were finding it hard to settle into their life on board, and the prevailing damp, exacerbated by being surrounded by ships off Finisterre in the fog, and the bobstay once again failing at the joining link, had lowered morale. Sailing close in to the Portuguese coast on a day of bright sunshine, the sight of all those people enjoying themselves was too much for them and they turned into the Tagus, where, going alongside, they brought up all standing against the stern line of the vessel in front of them and once again sheared that joining link. Portugal in 1953 was, of course, under the dictatorship of Salazar and their welcome wasn’t all that they had hoped for. They were whisked away to police headquarters and subjected to a serious inquisition before being released. They stayed a few days, having several repairs to make to the sail and finally replacing the vulnerable joining link with a shackle: less elegant but a lot more secure. The boat was tidied, re-stowed and dried out and they set off once more towards the Canaries.

Finally, they were in the trade winds: time to settle down and enjoy the passage. However, ‟although this meant cracking progress, it also meant more stressful sailing. With the wind dead astern, the risk of a heavy gybe was ever present, despite the boom preventer being permanently rigged.” From the log: ‟It is a very great strain this running before a fresh breeze and biggish sea with the boom squared off. A moment’s drowsiness and it is on top of one. Even with a light wind at night it is little better as the boom tends to fall in under its own great weight and scare the life out of us.” And of course, there was no self-steering to ease their load: they had to steer watch and watch about. In spite of the much-lauded benefits of a long, straight keel, these old gaffers seemed no more inclined to steer themselves than more modern boats.

Arriving at Gran Canaria was a relief and Ben felt more confident in his navigation. However, Las Palmas, in spite of police state bureaucracy, was full of thieves. At first they kept watch and watch about, but then realised that if they hired a ‛watchman’, this solved the problem. In return for being paid and fed, Juan made himself genuinely helpful around the boat and was something of a seaman, too: he laid out a second anchor one day when the wind suddenly shifted and increased, which probably saved Tern II from damage. But the initial disappointment these two young men felt, anticipating a full night’s sleep only to realise that they had to carry on their watches in case of thieves, can be imagined. Even 23 years later, when this reviewer first sailed there, Las Palmas was notorious for its thieves and its filth, and it was probably even worse in 1952.

It was almost the middle of October, but before they left, Ben set up their trade wind rig, which consisted of a square sail and raffee. He set it up differently from the way Claud Worth had, so that the yard could stay aloft and the sail could be brailed. He also had a spinnaker for lighter winds, a spare staysail to twin with the one on the boom, balloon staysail, jib topsail and a trysail. (Considering that they had provisioned with stores to take them all the way to New Zealand, most of which consisted of tins, one wonders how there was any room for the crew with all those sails to find a home for!) The rig completed, chronometer checked, and final provisions put on board, it was time to leave. Juan, their watchman, and some of his friends helped them get their anchors and Ben was distressed when Juan pleaded with him to let him join the ship so that he could get to the USA, where he wanted to work, save money and then send for his family. Peter and Ben had become fond of the man – he was almost part of the crew – but Ben felt he couldn’t undertake the responsibility: what happened if he weren’t allowed ashore in Trinidad? He refused, but ‟with the gnawing doubt that I had let him down. That feeling was to stay with me”.

Once clear of the islands and with a steady wind, they set up twin headsails: the staysail on its boom a spare staysail on a pole, the trysail sheeted in and the mizzen let out. After a few days, they replaced this with the square sail, and although there were some problems with chafe, the ship was easy to steer, faster and the boom was safely in its gallows. However, with no fore-and-aft sail, Tern rolled badly, putting each side deck under in turn and flinging the spray back to the helmsman; but the addition of the raffee reduced this and the boat went even faster, happily averaging 6 knots. Dealing with the chafe meant a daily climb up to the crosstrees to apply tallow, but the view made it worth while!

They settled into their routine, making a good team. Occupied with steering, cooking and navigation, they had little time together, although they shared a cup of tea in the afternoon, chatting in the cockpit and often found an excuse to have a tot of rum so that they could enjoy the company. Ben reckoned that by being busy, they reduced the risk of spending too much time in each other’s company and possibly falling out.

On 5th November, they sighted Tobago and just before dawn the next morning, they anchored in Port of Spain. Their landfall, which had seemed perfect, was made uncertain for a while by the unexpected sight of a lighthouse. As Ben remarks, only a fool assumes his navigation is right and that the chart and/or Pilot are wrong, but in this case the lighthouse was a very recent addition.

In due course the authorities cleared them in and, as ever, Ben seems to have been a little irritated at their demands. One can imagine that a young naval officer in the 50s, should still feel he lives in the time of the Raj, but throughout the book, I was surprised at Ben’s apparent lack of awareness of being a guest in another country. I would have expected the intervening years to have altered his attitudes and yet apparently, he still held a conviction of Northern European superiority, when the book was written. Or perhaps he was trying faithfully to record the reactions of his younger self. In Trinidad, they socialised with white people and observed the ‟essentiality of music to the black races” and of course, the steel bands.

After a couple of weeks, they sailed on to Panama, by way of Curaçao, where they rested for a few days, enjoying the then unspoilt town of Willemstad – and the relaxed attitude to bureaucracy. Then on to Panama where they were predictably impressed with the American presence and contrasted it with the poverty of the Panamanian cities. Ben cites an Ocean Cruising Club sailor in the early 2000s describing Colón as ‟poor, stinking filthy and dangerous”. Shirley Carter, who sails Speedwell of Hong Kong, had spent a considerable amount of time in the San Blas Islands, before moving on to go through the Canal. When she arrived there, she writes, she was ‟warned … of all the crime and gangs in the town. I listened attentively and thought of the many times I have walked through the town between the supermarket and the bus terminal without any problems”. Perhaps we experience what we expect!

They were boarded by a host of Canal Company officials, who organised them efficiently; Ben appreciated being told ‟exactly what to do”. He writes ‟One can only surmise how our treatment would compare with today, with the Canal under Panamanian control.” From all accounts, including this reviewer’s, the Canal is still run with efficiency and courtesy. In due course Tern II went through the Canal, buffeted by the incoming water of the locks, tearing a cleat out of the deck, and being chided for their inadequate motor. The Hiscocks had gone through several months earlier, also on a boat with a very small auxiliary engine, and there had been no drama. I suspect it was – and probably still is – very much the luck of the draw as to what ship you share the lock with and who is operating the sluices. They were well treated by the Americans and given much hospitality, which they very much appreciated. Indeed, while they were undoubtedly attached to their ship, she was not their home and they always seemed very happy to accept the chance to stay ashore when it was offered.

While in Colón, they met the great Jean Gau aboard his Atom. Ben writes that it ‟is not easy to avoid being judgemental” about single-handed sailors and the fact that they cannot keep lookout; and yet on several occasions on their voyage, he and Peter took the opportunity to turn in for the night when becalmed or hove to, with the risk of being run down. They were also very casual about burning their running lights. The 30ft Atom offered little danger to any other vessel while Jean was sleeping: the greatest risk is to the sailor himself.

Having been given free run of the Canal Zone Commissary, they topped up with good things from their dwindling stash of dollars and made their way towards the Pacific. As mentioned, their transit had its share of drama, including once again severely stressing the much-abused bowsprit, but they were towed for quite a part of the passage, which meant that they could keep to schedule and Ben writes interestingly of the history of the area. They stayed some time in Balboa, but on 20th December finally headed out into the Pacific and the mysterious Galápagos, whose human history obviously intrigued him. I’m not sure Ben was that interested in the natural world: his main interest was in the people he encountered. They had a frustrating passage to the islands, with lots of light winds, calms and even headwinds. On one windless night they were almost run down, when Ben had gone below to have a little snooze, the ship making no way. Peter never said a word. There are few things more frustrating than beating to windward on the ocean, when you are expecting a fair wind, and ‟a feature of all this agony in working to windward was frequent sail changing to help the boat’s performance.” They worked hard for every mile made good, and the Enchanted Isles lived up to their reputation, with overcast skies making it hard to take sights and poor visibility shrouding the islands. However, finally on 8th January, they dropped the hook in Wreck Bay.

As ever, there was the irritation of self-important officialdom, but finally they could go ashore and explore the tiny settlement. They went into a bar and there met the famous Karin, a Norwegian lady who had lived on the island for many years. Ben was highly impressed with this lady and had hoped to meet her, after reading W A Robinson’s description of ‟the girl Karin [who] tills the land with a handful of cut-throat peons and ex-convicts. She rides among them, unafraid of their great knives and machetes, with a tiny gun in her pocket.” There is more in similar vein! Unfortunately for Ben, Peter fell ill with asthma, so he was unable to follow up her invitation to visit. They left for Academy Bay where they spent time getting to know the other European immigrants, who made them very welcome and whose stories Ben recounts. He was very sad to leave them, but it was time to head on for the Marquesas.

They hadn’t wanted to leave and it seemed like the islands didn’t want to let them go. It took them a couple of days to drift away and at one time they were in danger of being set ashore by the current. Tern II had an engine which ran on paraffin, but required starting on petrol. It also had to be shut down while running on petrol, so that this was what was in the carburettor and fuel line when it was started. Both Peter and Ben seemed to have a real problem remembering this and had several close shaves because of it. There are probably few things more dangerous than an unreliable engine: not only do they engender a false sense of security, but because they have an engine, most people don’t carry a sweep or yuloh which can make all the difference in a calm.

The first thousand miles were somewhat trying due to fluky winds; Ben’s frustration with the difficult conditions was not helped by poor Peter succumbing once more to his asthma: sailing Tern single-handed was very hard work. This wasn’t the only incident either: a couple of weeks out, Ben fell over the side while ‛answering the call of nature’. Peter was sound asleep below and Ben was very fortunate not only to think of grabbing the log line, but even more that he was cool enough to realise that he had to slowly tighten his hold on it: his thought was that the deck fitting might be pulled off, but I suspect that a sudden snatch on the line would have snapped it clean off. His weight slowed the boat down and probably made her start heading up; perhaps it was that that woke Peter. Whatever it was, Ben was greatly relieved to see him appear in the cockpit and a few minutes later he was safely back aboard. Peter ‛broke out the rum bottle’!

Ben goes on to say that no doubt these days many people would be shocked that he wasn't wearing a safety harness, but as he pointed out (and as has been proven in several tests), being pulled through the water at speed would have probably resulted in his being drowned. They did rig a lifeline along the shrouds after this incident. I suspect that guardrails are the most effective way to keep crew on board.

The rest of the passage was a joy, with a fair wind and good progress until not long before they arrived, when the wind increased with a rough sea. However, Ua Huka appeared over the bow and before long they were anchored off Nuku Hiva, surely the most romantic of landfalls after a long passage. Here they stayed, wined and dined by the European community. Ben, a susceptible soul, fell in love again with another Karin and was once more reluctant to leave. However, a fortnight later, up came the anchor and off they set towards Tahiti.

The passage through the archipelago of low atolls known as the Tuamotus was notoriously tricky. They were hard to see from more than a few miles away and currents run between them in unpredictable fashion. Indeed, in spite of GPS, chart plotters and radar, there is probably as high a percentage of yachts wrecked there today as back in the 50s, including, of course, the rebuilt Gipsy Moth IV. Astonishingly, while drifting along one night, they decided to heave to and turn in because there was so little wind. Ben woke up to find they were almost on a reef and, in the light breeze, only just managed to turn the boat round and get away. They didn’t stop at any of the atolls, being discouraged by the Pilot which implied that a powerful engine was need to get through the passes. Instead they carried on to Tahiti and in light airs made their way to Papeete, where they tied stern-to to the quay.

Once again, the local European community made much of them. There were trading schooners and the odd yacht in the harbour, all tied stern-to, and the ‟hard-drinking, warm and convivial gang” welcomed the two men. The town ‟ran on a theme of liquor and sex”: perhaps not quite the magical South Sea Island they had been seeking.

Ben had contacted the navy in NZ to let them know he was still alive. The end of the voyage was in sight. On 23rd March, after an all too-brief visit to Tahiti, they sailed off, with just one anchorage more along the way: Moorea. How they regretted not coming sooner and spending time in this lovely and tranquil harbour, but it was too late now and the Admiralty were expecting him in Auckland. Once again, they drifted away in light airs, the islands apparently reluctant to let them go. Then the wind filled in and they set off directly for New Zealand. The only incident of real note was Peter suddenly being struck with severe toothache. Fortunately having been treated with painkillers, it sorted itself out. However, they were finished with easy sailing. The sea got colder, the wind had more weight in it: warm clothes were disinterred from lockers. They encountered a westerly gale – the first really strong wind in months. Ben commented that the ‟noise is possibly the most frightening feature of a gale” and on what a relief it is, to go from deck to the comparative peace of the cabin. Then they saw albatross, but these were accompanied by more strong winds, and freezing southerlies. Occasionally, the wind would die away and for a day or two they would progress gently under all sail before having to reef again. The final approach was somewhat nerve-wracking with overcast days making sights impossible. However a couple of quick snapshots gave them a position, confirmed by lights appearing on the horizon after sunset. They entered the Hauraki Gulf and at ‟0300 next morning we were bang in the middle of that entrance channel, making fast time in smooth water under full sail, and the memory of that moment has remained with me ever since”.

Annie Hill