Being a hero is all about timing

Oskar Speck in his kayak, SUNNSCHIEN. Australian National Maritime Museum

Oskar Speck's kayak voyage

When I recently revisited Paul Theroux’s book “The Happy Isles of Oceania” I found I was almost as fascinated by his Klepper kayak, as the journeys themselves.

Then I stumbled across this wonderful article written by Sabina Escobar, the Registrar at the Australian National Maritime Museum and I realised that travelling long distances in fold up, canvas covered kayaks, is not a new thing! I was unaware of Oskar Speck’s amazing journey and I suspect the story is new to many people. Here Sabina explains a little of this amazing journey and Oskar’s bitter sweet connection with Australia.

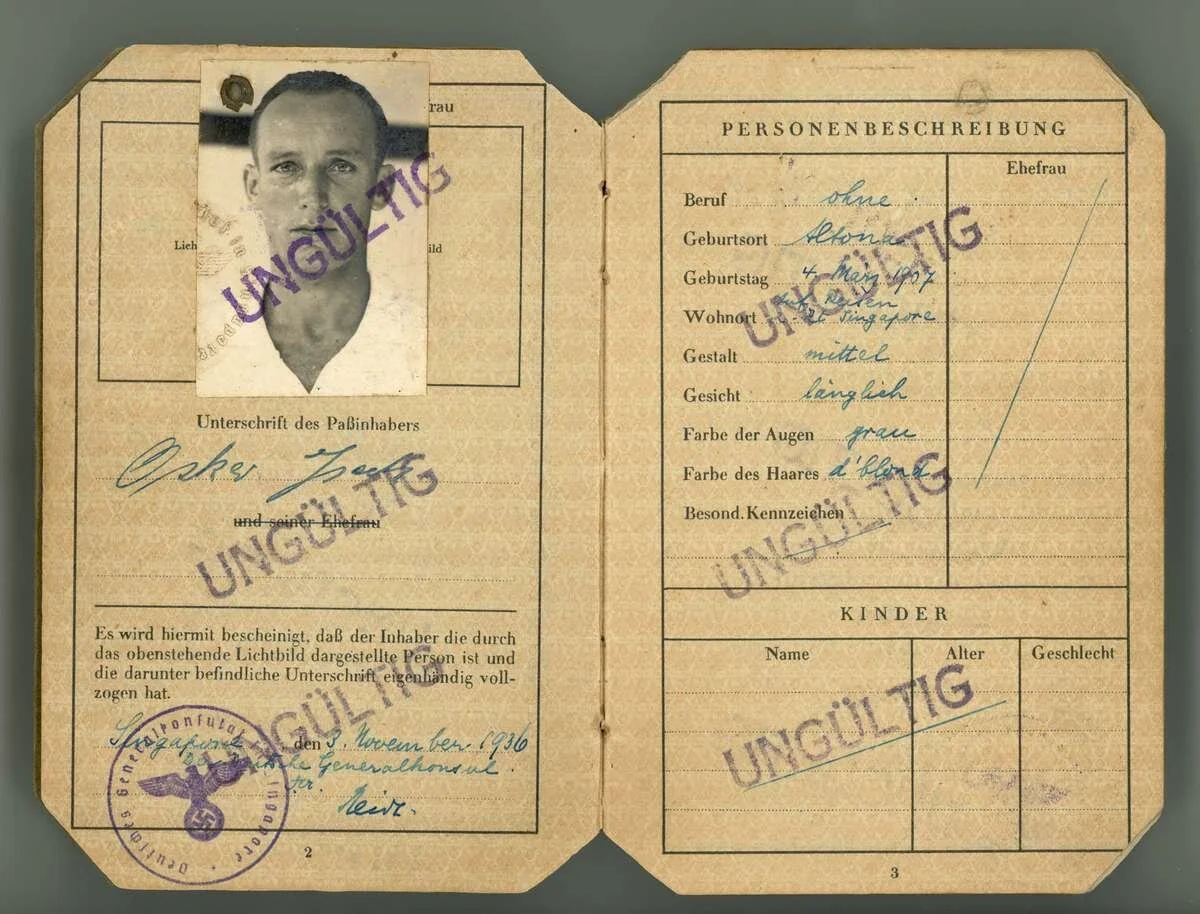

Oskar Speck’s passport. ANMM collection

As I was examining the letters, journals, photographs and reports of Oskar Speck, as though they were parts of a giant jigsaw puzzle, I started piecing together the life and the incredible voyage of this intrepid German, who spent seven years and four months paddling a collapsible kayak from his native town of Altona in Hamburg all the way to Thursday Island in the Torres Strait.

Oskar was born in 1907, one of five siblings. Just after graduation, he started working as an electrical contractor in a factory that closed in 1932 during the Great Depression. With no prospect of work, the keen canoeist and outdoor enthusiast saw this as an opportunity to take his collapsible kayak Sunnschien (sunshine) and venture to Cyprus to try his luck in the copper mines.

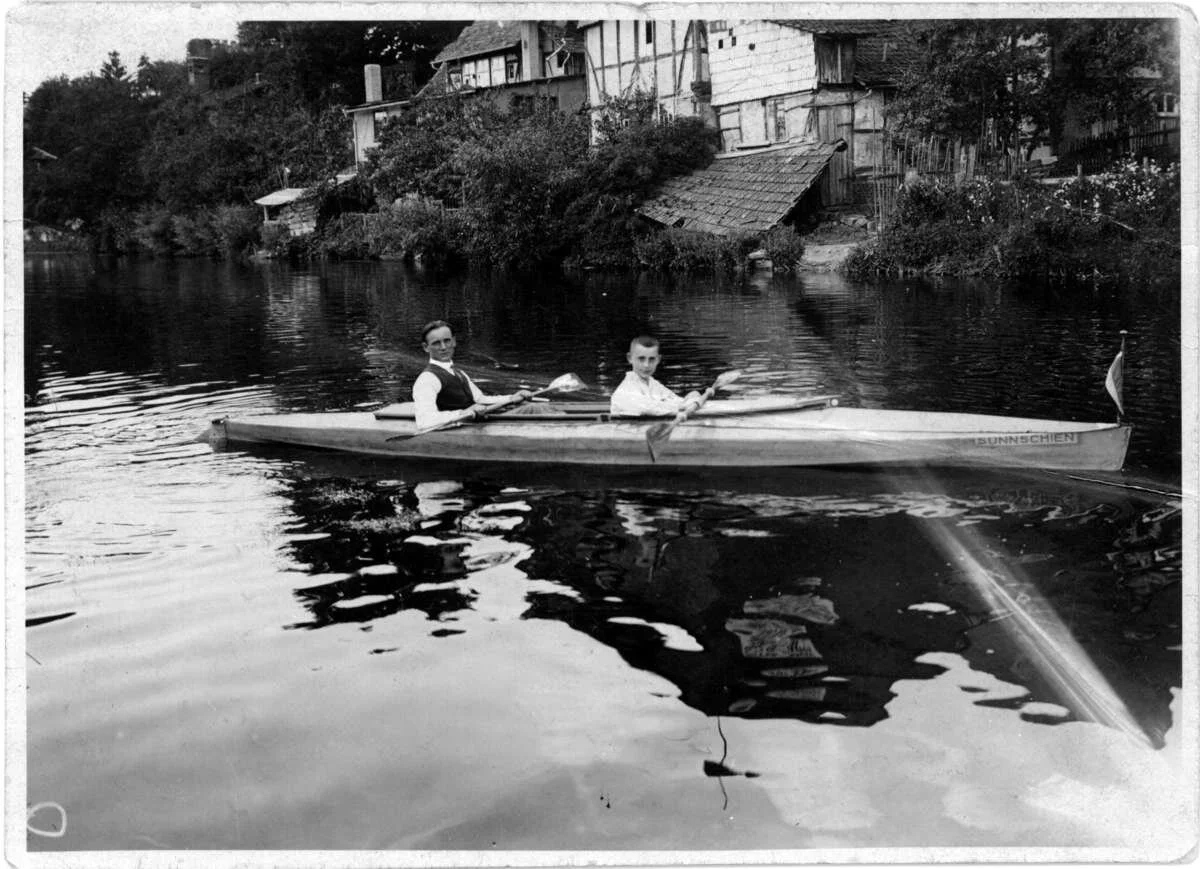

Oscar in SUNNSHIEN, Germany, circa 1930. ANMM Collection.

SUNNSHIEN was a double kayak produced by the German manufacturer Pionier Faltboots (which would become his biggest sponsor) which Speck modified for single use, leaving room for storage of equipment, clothing and provisions. The flexible wooden frame allowed it to be folded into a small bundle for carriage and storage.

With a small sum of money collected by the sale of his belongings and contributions from his family, Speck set off from Hamburg on 13 May 1932, when Hitler was almost unknown. Armed with a kayak, two paddles, a camera, film, clothing, a pistol, documents, sailing charts and a prismatic compass, he paddled down the Danube through central Europe towards the Mediterranean.

During his voyage he kept in touch with family and friends by letters. Through them he learnt about the changes of the political panorama in both Germany and the rest of Europe. He kept the letters with the hope of one day writing a book about his voyage.

‘We have had another round of elections last Sunday. I think it was the fifth this year. The result is nil. The Nazis lost a bit and the Communist gained a bit …’ (From a letter from his brother Seppl dated 10 November 1932).

Letter to Oskar from his friend Georg Puschel dated 1935. ANMM Collection

Once in Cyprus, he quickly realised that this nautical adventure was more enticing than working in the mines, so he decided to continue to Syria and then to challenge himself by paddling down almost the whole length of the Euphrates. ‘I wanted much more to make a kayak voyage that would go down in history’ (The Australian Post, 1956).

While waiting for a replacement kayak after his broke in the Persian Gulf, he contracted malaria, a disease that would accompany him for the rest of his voyage. Pionier replaced Oskar’s kayak four times in total, and in return, used Oskar’s adventures and photographs to promote their products.

He then continued to India and paddled his way along the coast. It was 1935 and Oskar was already a well-known figure in Germany, as many magazines and newspapers were reporting on his voyage. Capitalising on this and his good English he gave talks and presentations to mostly English expats who were more than happy to donate to the cause and recommend him to other connections living in Asia.

‘In Germany, I was a recognised kayakist before 1932. As my voyage progressed and reports of it went home from Cyprus, Greece, from India, I became acknowledged as the most experienced sea-going kayak expert in the world.’

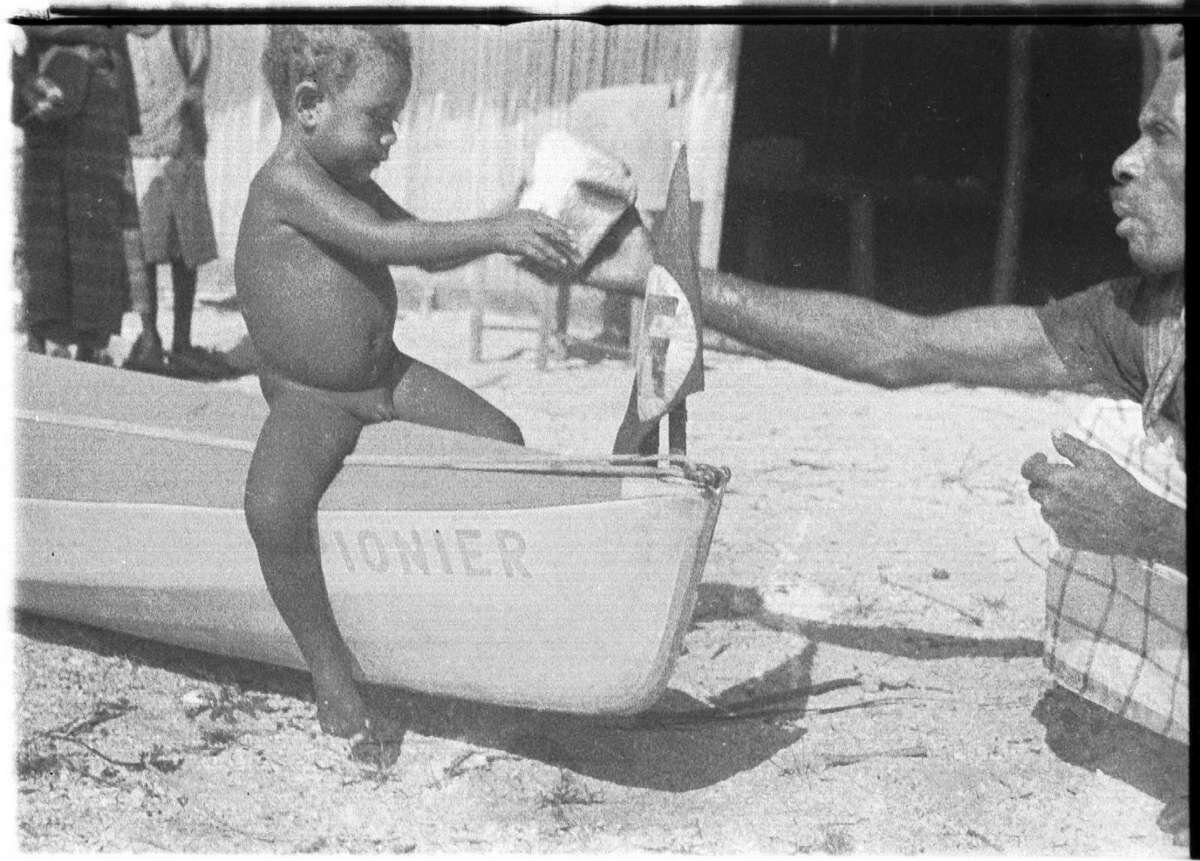

Crowds checking Oskar’s kayak circa 1933. ANMM Collection

During 1936 Speck paddled his way along the Bay of Bengal, Malacca Strait and the Dutch East Indies. While in Singapore, he collected another kayak and paddled on to Indonesia. During this time, he was pressing friends and papers to get more coverage of his story but the political turmoil in Europe and the Olympic Games were getting all the attention.

Malaria and the monsoon slowed Oskar’s progress and he only managed to get to the coast of Dutch New Guinea in 1938. Here, the authorities were unsure if the German visitor should be arrested or permitted to continue his trip. After more delays, he finally continued towards Australia.

Oskar in Papua New Guinea. ANMM Collection

On his arrival to Daru Island, the officer in charge decided not to arrest Oskar but instead let him complete his dream and reach Australia. But it was his luck that in September 1939 two constables were waiting for him at Thursday Island. After congratulating him for his feat, the officers told him that he was now classified as an ‘enemy’ and had to be arrested and transferred to an internment camp.

After a month in Thursday Island, he was transferred to Brisbane and then Tatura Interment in Victoria. He escaped the camp but was quickly recaptured and sent to South Australia until his release at the end of the war.

Toddler on SUNNSHIEN. ANMM collection

Oskar had kept all the letters and newspapers clippings in preparation for the talks and conferences he was to give and the book he was going to write.

‘So ended one of the most fantastic and dangerous voyages ever accomplished by an individual … I have reached my goal, but not one of the numerous doubters would ever find out and my modest success in reaching Australia in my folding boat would be swallowed up in the imminent global catastrophe’.

Sadly for Oskar, by the time he was ready to tell his story and show the world images of his amazing voyage, the world had moved on, so he never got to be the hero he dreamed of being.

Many Thanks to Sabina Escobar and the Australian National Maritime Museum for allowing us to reproduce this article