Classic Performance Part 1

Classic Q class racing to the Universal Rule

In this first of a five part series by Ian Ward, SWS is venturing into an area of the sailingworld that we haven’t really as yet explored. Ian writes …

As a custodian of a long heritage of classic yachts and their designs, I have sought to understand the fundamentals of the behavior, handling and performance differences between classic and modern yachts, which is encapsulated in the attached series of articles. I try to explain these differences and hope to convey what causes them, as well as look forward to what might be. I know these articles may be quite 'technical' and do not relate directly to 'wooden boats' but they certainly relate to 'classic yachts'

PART 1 – THE RULES

Classic Yachts

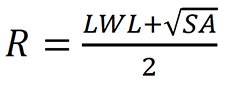

Designed and constructed in a previous era, we now regard “classic” yacht designs as iconic. Their graceful lines being very much a product of the racing ‘rules’ prevailing at the time, restricted simply by either their waterline length or sail area, while the Seawanhaka rule of 1887 included both where

but did not include displacement.

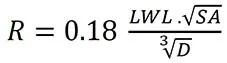

(R=Rating, LWL=Length at Waterline, SA=Sail area, D=Displacement)

KNOT-IN-IT racing under the Seawanhaka Rule

These were essentially open development rules, where the designer was provided utmost liberty to improve efficiency and design faster boats within quite liberal parameters. The combination of a fast boat and skilled crew won the race and advances in design were readily recognised.

They proved fast and efficient for their proportions, although these rules tended to foster excesses in sail area, overhangs and light construction, as no restrictions were placed on displacement and overall length.

To limit these excesses Nathanial Herreshoff introduced the Universal rule in 1903, which recognised the fundamental importance of all three key elements determining the driving force and resistance of a yacht. This simplistic rule required a trade-off between Waterline length, Sail Area and Displacement to optimise performance in accord with the formula:

although this relationship was not based on any measure of hull resistance or efficiency. As a result, yachts competing under the Universal rule were effectively penalised for low D/L ratio and high SA/D ratio, favouring instead longer waterline length, heavy displacement and relatively small sail area.

Size groups were set to encourage level racing between boats. From J class with 76’-87’ LWL through to S class at 17’-23’ LWL.

In Scandinavia the Square Metre rule was preferred, which arbitrarily limited the ‘nominal’ sail area, leaving scope to optimise length, beam and displacement, encouraging the gracious lines of these boats which ranged from 75sqm through 50, 30 to 10sqm to provide level racing, one of the most popular being the 30 sqm class. As the actual sail area was not fully measured, large overlapping headsails were the order of the day, along with extreme overhangs and light displacement.

Further restrictions on overhangs were subsequently introduced to the Universal Rule in 1905, which became the International Rule, leading to the popular Metre classes such as 12m, 8m, 6m and 5.5m.

These were essentially level rating classes, where optimisation of the hull and rig was rewarded as well as challenging the skipper and crew. It was easy to judge the best designs ‘to the rule’, as they were consistently fastest around the course, as no handicaps were involved. This concept has continued today in more refined box rules such as the Open 60, Class 40, TP52, Mini 6.5 etc.

One design

While these quite open development class rules created a marvellous proving ground. At times, the best of these designs could inspire One-design classes such as the International Dragon which suited those sailors wishing to pit their skills against each other, eliminating the design of the boat from the contest altogether. Some of these classes allowed adjustment of sails and rigs, while others were more strictly controlled in every aspect. One design classes have consequently become the most popular type of racing yacht, regularly updated with newer versions which reflect the latest design trends in the development classes.

Ratings

Despite the undoubted success of the International rule in producing efficient boats with great sailing qualities, it was also recognised that these classic development class yachts were not so suitable for cruising or ocean racing due to their long overhangs, low freeboard, light construction and narrow hulls with limited internal volume.

Rule makers on both sides of the Atlantic determined to remedy these perceived limitations by introducing the RORC and CCA rating rules for offshore racing, which further arbitrarily restricted certain features by introducing construction scantlings, even more limits on overhangs and encouraging specific rig configurations.

As these rules became more complex, loopholes inevitably opened, allowing designers scope to exploit them. This trend became even more excessive with subsequent IOR and IMS rules which, perhaps unintentionally, encouraged large distortions in the hull shape, rigs and instability to both ‘optimise’ & thereby circumvent the rules.

Consequently, winning races became a challenge to outsmart the rule maker as much as to produce a better boat. Unfair shapes with rule cheating ‘rating’ lumps and bumps, poor stability, structural failures and handling issues became the norm, as the design challenge was to find the fastest sailing configuration which would ‘appear slowest’ under the version of the rule applying at the time.

These new rating rules arbitrarily favoured lighter displacement, wider hulls with more form stability, lower ballast ratios and reduced surface area, leading to a completely new type of sailing craft typified as an ‘offshore dinghy’. The newer boats were significantly faster ‘for their overall length’ than their forebears although, they were not particularly competitive under the original Universal Rule to which the original classic boats were designed.

An obvious consequence of these new rules was that the older, heavier designs were excessively penalised for being ‘too fast’ under the new rules, hence they could not win under such a rating system and consequently became obsolete.

Handicaps

For owners, skippers and designers at the pinnacle of the offshore rating classes such as IOR, One Ton, Half Ton etc, this provided an ongoing fascinating challenge, but for owners of superseded boats, there was a desire for improved level competition where the design of the hull is offset by a suitable handicap, leaving racing as a challenge between skippers & crew, in a similar manner to one-design craft.

This has led to a concerted effort to use the results of tank testing, VPP and CFD tools to design an effective ‘handicapping system’ without the arbitrary distortions and excesses of the IOR and IMS rules, while avoiding the inbuilt obsolescence of development classes. IRC ratings have proven a wonderful innovation as an egalitarian handicapping tool as it caters for those who wish to race on a ‘level playing field', but with different types of boats. In principle, IRC predicts the actual performance of an individual yacht, consequently being design agnostic, as both fast and slow boats all have an appropriate handicap and can win races if sailed well.

This effectively negates the ability of the designer to be rewarded for producing a faster or more efficient boats, much to their chagrin. As improvements are handicapped and poor designs compensated, it is no longer necessary to design a faster or more efficient boat to win races as the idiosyncrasies of each design are catered for by these modern handicapping methods, leaving little room for designers to innovate or even find loopholes.

The very popular performance PHRF handicapping system has a similar effect to IRC, while PHS also allows for the ability of the crew. It seems that there is no longer a reliable method available to compare the efficiency of different yacht designs based on its fundamental proportions, other than within the narrow confines of box rules.

Unfortunately, despite the promise of equal treatment for all designs under IRC, it does rather appear that specific type forms of boat are still favoured, especially those with truncated ends and wide, light hulls. Once again leaving little room for classic designs in modern racing. As a result, an independent classic rating formula CRF has been developed to handicap Vintage, Classic and Modern Classic yachts.

Latest design trends Clearly, the quite different arbitrary rating and handicapping systems adopted over the years have hugely influenced yacht design trends. Strangely, it appears that as either a result of, by default, or perhaps in the absence of any other suitable guide, there is now a popular trend of comparing the relative performance of different designs by judging rather simplistically on the basis of ‘speed for overall length of the hull’. This latest unofficial design criteria is perhaps best encapsulated by the epithet coined by Julian Everett as ‘internal volume for marina fees’.

Despite the overall length of a boat having no direct bearing on its speed, the upshot is that the newer, lighter, truncated boats are clearly proven to be much faster by this measure, so they are quite naturally popularly considered and promoted as being more efficient design improvements. This is perhaps unsurprising, after all, most aspects of yachts are based on their overall length. Not only marina fees, but also the length description and category of the boat, class racing fleets, insurance costs, sales prices, shipping costs, club membership & slipway fees etc, are all based on the overall length of the hull.

As a result of this rather natural tendency to produce ever ‘faster’ boats for their overall length, they are becoming ever lighter, with relatively larger sail area and longer waterlines, in a similar vein to the effect of the excesses of the original length-based rules of the late 1800’s.

This trend seems to have forever changed the face of yacht design as truncated ends give the longest waterline length and therefore produce the fastest boats for their overall length. Light, wide hulls provide the greatest form stability for the least displacement, to hold up relatively larger sail area.

Hence the current design trends are somewhat predictable, demanding ever increasing righting moment in the form of wider hulls, live crew ballast, deep fin keels with lead bulbs, water ballast, canting keels and DSS lateral foils to support the ever larger rigs.

Despite the obvious fascination of the current breed of sailors for faster craft with more thrills, spills, fashionable shapes, super materials and technical complexity it is not so clear that these boats always perform to their potential, especially when compared on the basis of their fundamental proportions which is addressed in PART 2 of this series next week.