Classic Performance - Part IV

In this fourth piece by Ian Ward we look at what makes

A BALANCED YACHT

Rig Balance

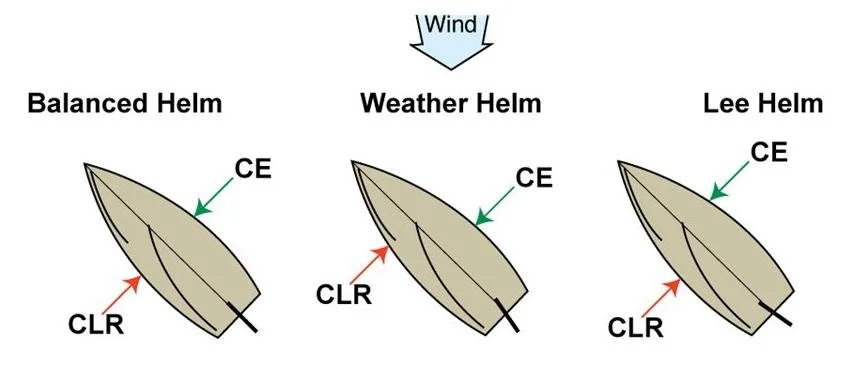

It is well known to sailors that the centre of effort ‘CE’ of the rig when sailing upwind needs to be aligned with the centre of lateral resistance ‘CLR’ of the hull for the boat to be ‘balanced’. If the rig is placed too far forward, the boat will have lee helm and if placed too far aft, it will have weather helm, even when upright. Both weather and lee helm, requiring correction using the rudder increase resistance and slow the boat.

Influence of the relative positions of CLR and CR on helm balance

The ability to trim sheets, adjust mast bend with the backstay, rake the rig, play the traveller, heel the boat, rake the centreboard etc. are all the subject of a huge range of texts on sailing technique and boat tuning which are aimed at maintaining this balance, keeping the boat under control and sailing fast. These techniques are typically used to counter any imbalance in the heeled hull or turning moment of the heeled rig to leeward and keel to windward.

Hull balance

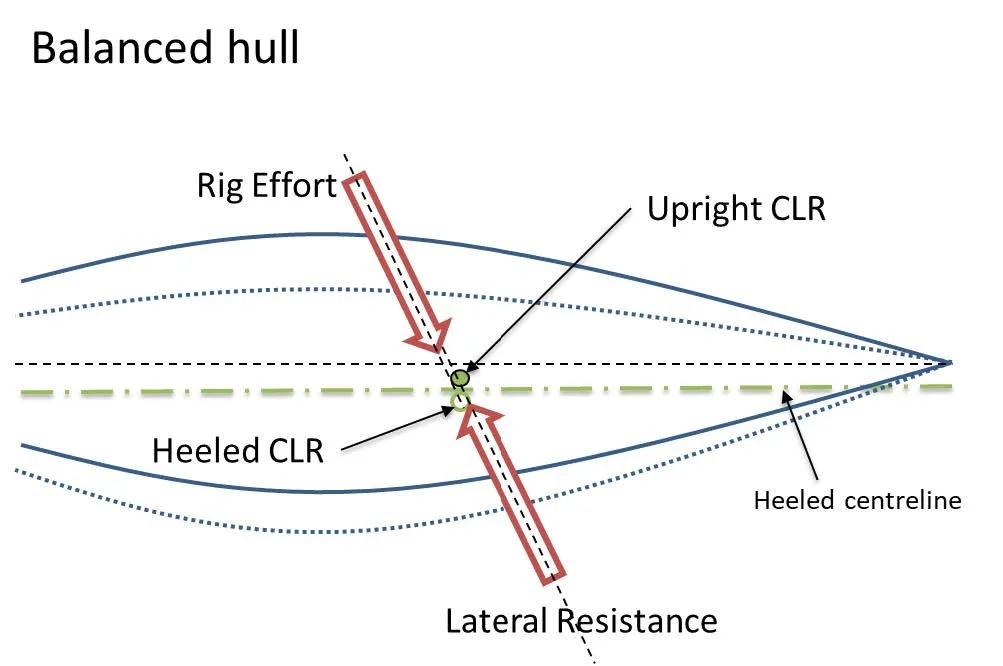

As a yacht heels, its hull shape below the waterline typically becomes asymmetric to the water flow, which alters the position of the Centre of Lateral Resistance ‘CLR’ of the hull, usually moving further forwards with increasing heel. This in turn induces a misalignment and imbalance in CE and CLR, resulting in a ‘broaching moment’, producing weather helm, which increases with increasing heel angle. This effect is rather like that of an asymmetric hydrofoil in which the centre of pressure moves forward with increasing angle of attack. It’s effect is akin to moving the fulcrum point of a beam balance arm, producing a large turning moment due to the force from the sails.

A relatively small imbalance of the hull can result in moving the heeled CLR forward, producing a significant ‘Broaching’ moment due to misalignment of CE and CLR.

As weather helm increases, the entire mainsail is eased to reduce the helm which reduces available power and increases drag. Twin large rudders aft and geared wheels are often employed to help the skipper maintain control which also increase drag. If the boat heels too far, it produces an irresistible broaching moment, which is exacerbated if the boat is also directionally unstable. It is at this point the skipper cannot resist the force on the tiller, or the rudder stalls and the boat broaches uncontrollably, sometimes rounding up into the wind and stopping altogether.

Many modern hull shapes developed for downwind speed tend to feature fine bows and wide flat sterns, typically exhibiting poor hull balance, which is a fundamental cause of weather helm, rounding up and broaching in these designs.

Too much heel angle on wide-stern unbalanced hulls causes weather helm, requiring a lot of correction from the rudder to keep the boat tracking straight.

A well-balanced hull however, retains a stable longitudinal position of CLR as it heels. This property is crucial to ensuring the balanced helm of a yacht. If the boat is also directionally stable, it is even possible for the hull balance to be matched to the turning effect of the heeled rig, enabling the boat to free-sail ‘hands free’ at any heel angle. Such boats can maintain full power at all angles of heel without the need to adjust the sails or increasing drag from corrective steering using the rudder.

In a well-balanced hull, CE and CLR remain aligned as the boat heels.

Typically, long narrow hulls such as those of classic yachts are well balanced, along with scow hull shapes and catamarans.

Well balanced hulls can typically be sailed with a tiller, small rudder and do not gather any significant weather helm as they heel .

It is also possible to achieve excellent hull balance in conventional cruiser/racer yacht hulls and over the years several techniques have been developed such as Turner’s metacentric shelf analysis used by Tom Harrison-Butler, Robert Clark, AA Symmonds, Douglas Phillips-Birt, Jack Welch and Wally Ward. More recently, John Ward developed the Intrinsic hull balance method which is applicable to a wider range of yachts.

These designers are admired for their well-behaved boats with good sea keeping properties, without the tendency to gripe or broach in heavy conditions.

Free sailing

A well-balanced and directionally stable yacht can actually ‘free sail’, where it can be sailed ‘hands free’ through gusts and lulls, gunwale down, responding to both lifts and knocks as it makes it own way across the bay. Where your role as skipper is purely to provide occasional guidance with finger-tip helm, to anticipate lifts or tack onto the next shift.

Most yachts can attain a temporary state of equilibrium, where sail trim is adjusted to produce a neutral helm. It is even possible with the helm lashed, that some yachts can ‘free sail’ effectively, even in a shifting breeze. The challenge arises when the wind strength varies, causing the boat to heel with the gusts, as any imbalance of the hull can induce weather helm. There are however some boats in which you can experience ‘pure free sailing’, where the boat naturally responds, maintaining harmony with the elements to sail itself in a wide range of wind conditions and heel angle with the helm released or even rudderless!

A ‘free-sailing’ yacht can even sail from hard on a wind, to a broad reach, just by setting the sails appropriately, without the need to touch the helm.

Well-balanced yachts and even catamarans can ‘free sail’ across a wide range of conditions ‘hands free’ or even rudderless!

Classic yachts naturally possess the key ingredients to be both directionally stable and well-balanced, providing the potential for them to ‘free-sail’. This is not the case for modern fin keeled designs with spade rudders, which are directionally unstable when the helm is released.

In PART 5 of this series the characteristics of ‘modern classic’ designs are discussed.