The Mignonette

The loss of the yacht Mignonette resulted in a court case that is part of law studies in both England and America.

Sketch of English bark Mignonette by Tom Dudley (1853-1900)

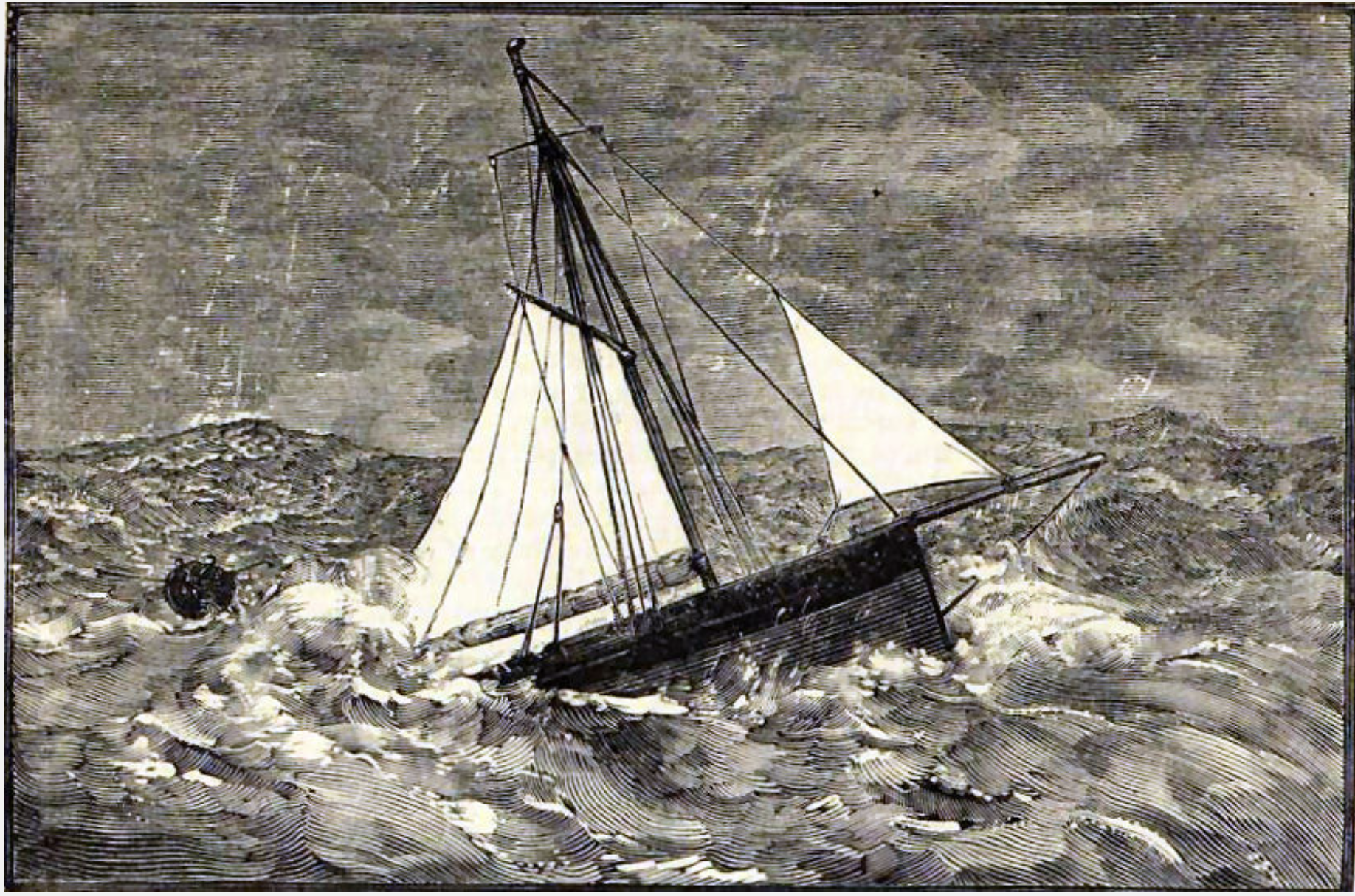

In 1884 two men appeared in court in Exeter, UK, charged with murder. The two had formed part of the crew of the 52ft, 19.43 registered net ton yacht Mignonette which had been bought by Jack Want, a Sydney lawyer and Commodore of the Sydney Yacht Club. He had been in England in 1883 and purchased the yacht before returning to Australia by steamer. The Mignonette had been built very strongly for the previous owner as a Dogger Bank fishing smack. It had a beam of 12 .4ft, depth of 7.4ft and was insured for £550, about half its actual value. Want had difficulty hiring a crew to sail his newly purchased yacht halfway round the world to Sydney, and it wasn’t until the following year that he found four men willing to undertake the voyage. They were Captain Thomas Dudley, the mate Edwin Stevens, Edmund Brookes and a 17 year old cabin boy named Richard Parker. The Mignonette left Southampton on 19 May 1884, and after calling at Madeira on 5 July was some 700 miles from Saint Helena, the nearest land, running before a gale. Dudley gave the order to heave to so the crew could get some rest, after which Parker was sent below to prepare tea. Almost immediately a large wave struck the yacht, washing away the lee bulwark and opening up the butt ends of the planks at the stern. The yacht began to sink, so the 13ft lifeboat was hurriedly launched, but was holed in its thin ¼ inch planking in their haste. The Mignonette sank within five minutes of being struck by the wave, the crew managing to save only some navigation instruments, no water and just two tins of food. These turned out to be two tins of turnips.

The Yacht Mignonette

A sea anchor was improvised, and on 7 July one of the tins of turnips was opened and shared. Two days later Brookes spotted a turtle which Stephens dragged on board. This and the second tin of turnips lasted about a week. The crew had failed to catch any rainwater, and began to drink their own urine. About 20 July Parker became ill through drinking seawater. Discussions on survival ensued until on about 23 or 24 July Dudley suggested that it was better that one of them die so that the others might survive. He suggested that they draw lots, but Brookes refused to take part. Dudley then suggested to Stephens that the obvious person to die was Parker. He was, according to them, dying and may have been in a coma. Parker was killed by Dudley pushing his pen knife into the boy’s jugular vein, with Stephens holding the victim’s legs in case he struggled. The three men then drank blood caught in a tin and fed on Parker’s body, with Dudley and Brooks consuming the most. They also managed to catch a little rainwater, and this and Parker’s flesh kept them alive until 29 July when they sighted a sail.

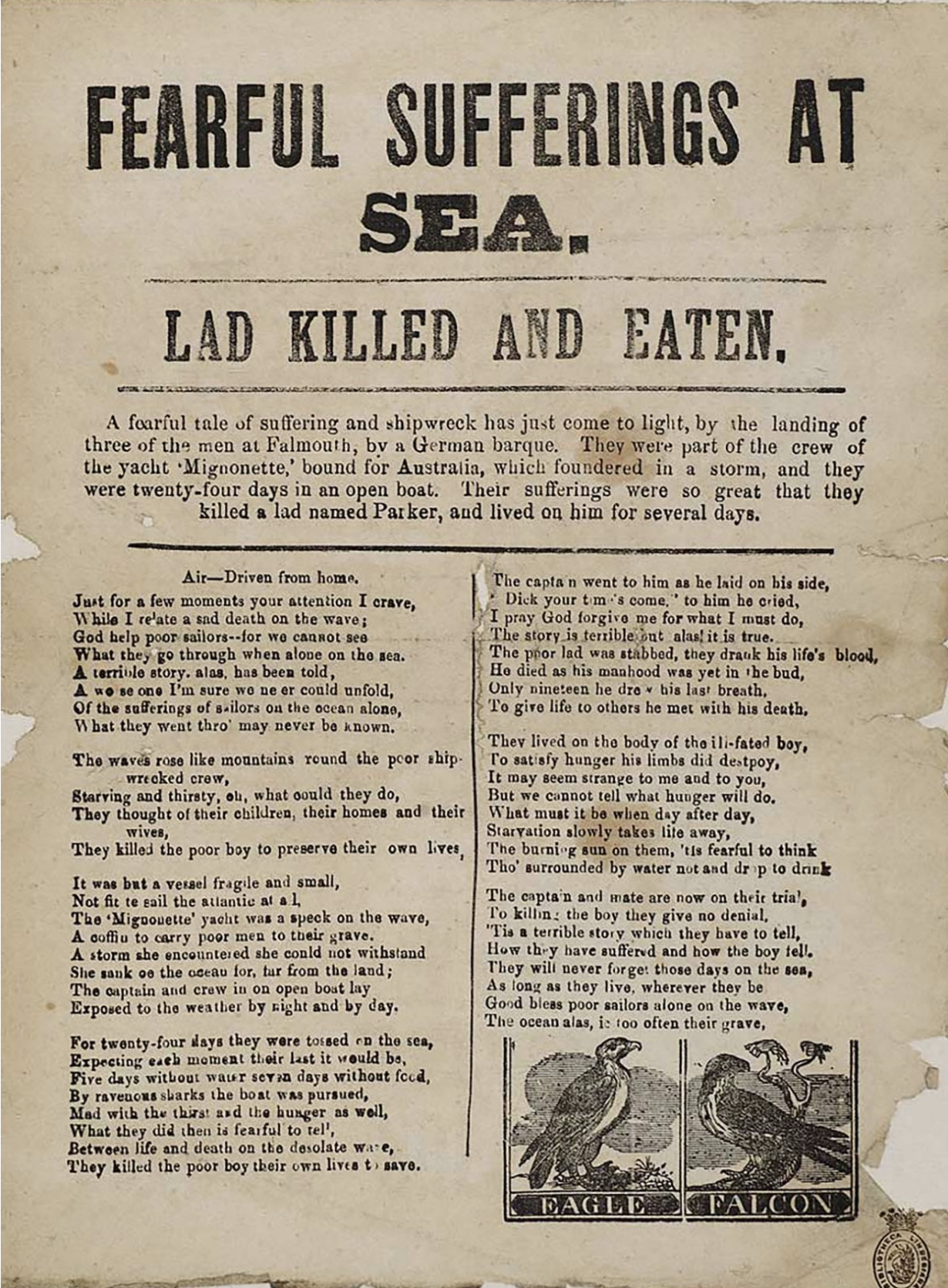

The German barque Montezuma picked them up and returned them to Falmouth, arriving on 6 September 1884. As was required by law statutory statements were taken regarding the loss of the Mignonette and what occurred subsequently. Both Dudley and Stephens were candid regarding the killing and cannibalism believing themselves to be protected by a ‘custom of the sea’. This was that the necessity to save lives was a defence against murder.

The authorities did not agree, and the Home Secretary, after consultation with the Attorney General and Solicitor General, decided to prosecute. Meanwhile, much to the annoyance of the Solicitor General, public sympathy had been firmly on the side of the charged men. The prosecuting lawyer realised that the public sentiment and a lack of witnesses (the only witnesses were the three men, and they had a right to silence) would cause serious problems for his case. He circumvented this problem by stating that he would offer no evidence against Brooks, and requested that he be discharge. Brooks was then called to give evidence as a Crown witness, and that evidence and that of those who had heard the survivors relate their story formed his case. The trial in Exeter opened on 3 November, and the men had a QC for their defending counsel, paid for by public subscription. Both Dudley and Stephens pleaded not guilty, but it was evident that the judge, Baron Huddleston, had made up his mind that they were guilty, and wished to settle the contentious custom for ever. The judge had in fact already produced a special verdict he had written previously without waiting for the jury’s decision. The two men were found guilty with the jury attempting to add facts to their decision. The judge disregarded these facts, ending his verdict with the statement: But whether upon the whole matter, the prisoners were and are guilty of murder the jury are ignorant and refer to the Court. The trial was then adjourned to be heard in London on 25 November 1884.

The Yacht Mignonette : Illustrated London News (London, England), Saturday, September 20, 1884; pg. 268; Issue 2370

Between the adjournment of the hearing and 25 November Judge Huddleston realised he had made a serious error-describing Mignonette as an ‘English merchant vessel’ and had altered that to read ’yacht’. This tampering with the written court record and a number of other factors resulted in a further postponement until 4 December. After some legal argument the court found there was no defence of necessity to a charge of murder, and Dudley and Stephens were sentenced to death, but with a recommendation for mercy. The two were sentenced to six months in prison, and were released on 20 May 1885. This case is still taught at Law Schools in England and America.

By an extremely strange coincidence the author Edgar Allan Poe had in 1838 written a story, The Narrative of Gordon Pym of Nantucket, a whaling novel in which a man named Richard Parker was eaten by fellow shipwrecked sailors.

It is believed that Poe took the name of Richard Parker for his character in the novel from the man hung in 1797 after the famous Nore Mutiny.

This article by Peter Worsley first appeared in the The Maritime Heritage Association’s Quarterly Journal. The Association is dedicated to preserving and promoting the maritime heritage of Western Australia.