Dead in the Water in 1866

Story by Russell Kenery, Illustrations by Andrew Murray

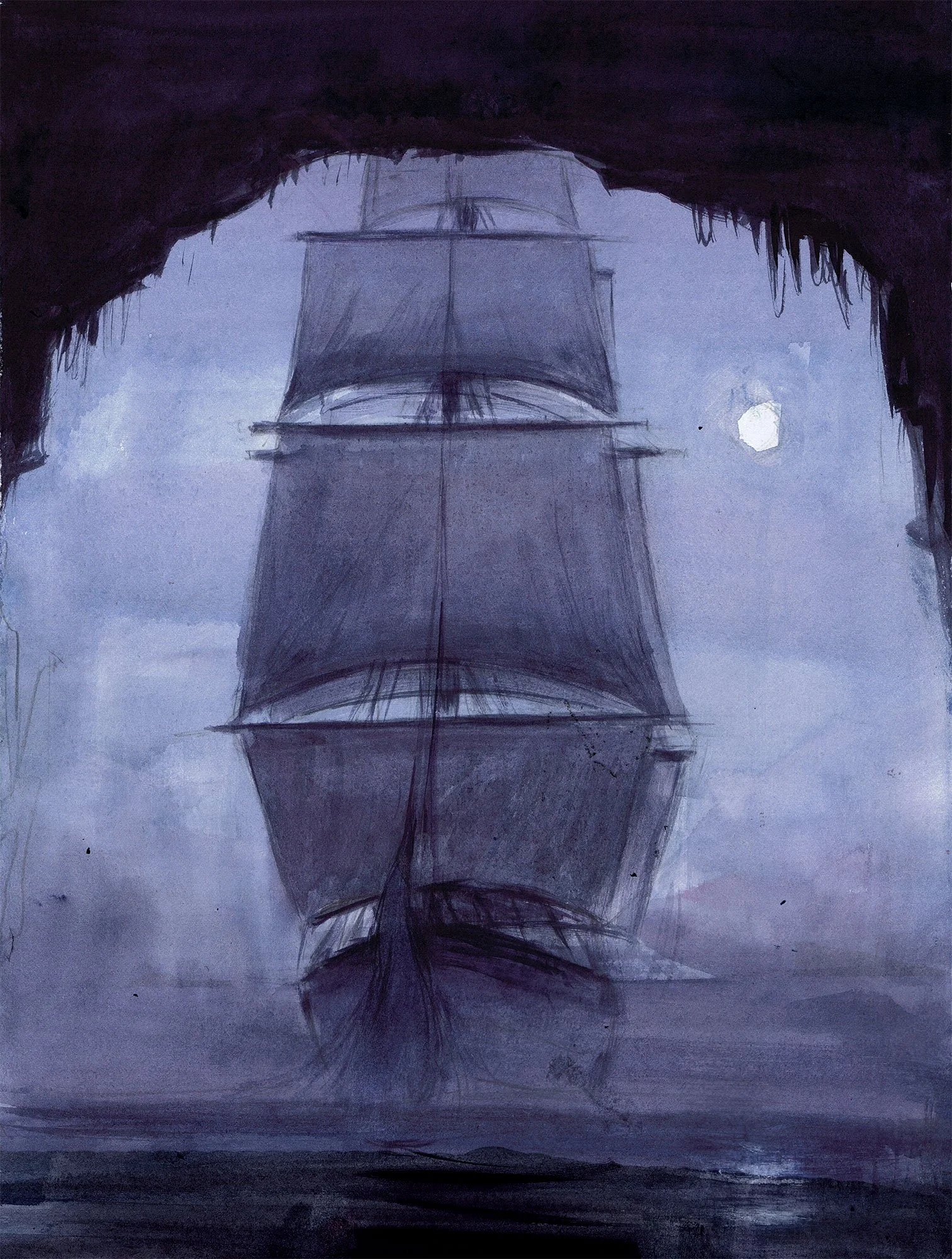

The big three-masted barque, General Grant, was becalmed south of New Zealand, then swallowed by ‘a horrible cavern’. When she sank, it triggered an astounding story of survival.

The three-masted 179ft GENERAL GRANT departed from Melbourne for London on 4 May 1866, with sixty-three passengers and crew. Captain William Loughlin had often sailed the “Great Circle Route.” From Port Phillip Bay, he headed southeast from the Bass Strait to pass below New Zealand and down south for the Furious Fifties to sweep them east to Cape Horn.

One week into the voyage, the wind faded, and a dense sea fog prevented navigation sun sights for some days. Laughlin knew they were near the Auckland Island archipelago, 250NM south of New Zealand, and the GENERAL GRANT could only blindly grope her way along. On the night of 13 May, the light breeze was barely sufficient to maintain steerage when a lookout suddenly saw land loom out of the fog on the port bow. Loughlin mistakenly believed this was the southwest cape of Auckland Island, so he swung to starboard to clear away to the southeast. Unfortunately, the land was Disappointment Island and soon, out of the fog, a line of cliffs loomed. GENERAL GRANT was heading directly for the western shore of Auckland Island. The wind fell away, stalling the ship in irons, the limp sails useless in the dead calm. The prevailing southwest current and a long swell relentlessly drifted GENERAL GRANT shoreward, then to her doom. A seaman swung the lead-line and found no bottom, but even if he had, it was too late. On leaving port ships unshackled the anchor tackle and stored it below to avoid anchor chains slamming on the bow in heavy seas: re-rigging anchors takes hours. The passengers were now all on deck, staring up at sheer 400ft cliffs that echoed back their voices.

A horrible crunch was heard out of the darkness as the bowsprit’s jib-boom extension snapped off against a protruding crag. GENERAL GRANT recoiled, slowly turning 180° until her stern crashed into the cliff, an impact that mortally damaged the rudder and broke the ribs of the helmsman. Rudderless, drifting, she again recoiled and slowly swung around to where the cliff-face opened into what one survivor called “the horrible cavern.” GENERAL GRANT was slowly drawn, bow-first, into an enormous sea-cave so large the mighty ship was swallowed whole. It was almost unbelievable. She paused momentarily as a topgallant snapped off on the cathedral-like entrance, then was washed relentlessly into utter darkness. As topgallants and spars scraped the roof and walls, they snapped and crashed to the deck along with rigging, chunks of earth, and rocks.

The GENERAL GRANT shortly before its horrible demise.

Loughlin had oil lamps lit, and their faint glimmer revealed a scene bordering on the absurd. The entire ship was in a massive chamber, later measured as 180ft high and 150ft wide, a situation so bizarre Loughlin gave no coherent orders for some time. Although the ship was taking water, Loughlin decided not to launch the longboats before daylight because the confused backwash from the heavy swell rolling in made it very dangerous for the small boats.

The rising sun brought an increasing wind and sea swell that forced GENERAL GRANT harder into the cave, where she ran aground at the bow. They launched two of the three longboats and lowered people by a rope off the stern into them, and both boats escaped the cave safely. But the steadily rising swell battered the mainmast down into the keel, causing more chunks of rock and rigging to smash down to the deck, and then GENERAL GRANT rapidly began to sink. Pandemonium broke out. Too many people piled into the last longboat, still on deck, and it swamped when GENERAL GRANT sank. Loughlin had climbed up the rigging to the mizzen-crosstrees and waved as he went down with his ship. A terrible crescendo of wailing rose in the massive echo chamber, as those still on board drowned, then faded to an equally awful silence.

The “horrible cavern” was photographed from out at sea in 1986 by John Dearling

The ship had disappeared entirely, leaving some flotsam and jetsam and two 23ft open boats overladen with survivors and provisions. The small craft fourteen survivors, but there was nowhere to land along the long line of sheer cliffs. They headed for Disappointment Island, a tantalising 6NM away. But both wind and current were against them, and they spent an exhausting night rowing to hold a position in the lee of a rock, today’s Needle Peak. It was a brutal 24-hours before they finally landed on Disappointment Island. It was nightfall, but they found water, shared small rations, then rested as best they could. When the weather became favourable, the two boats set off and rowed 15NM around the northern end of Auckland Island and found a sheltered cove known to the Southern Ocean sealers as Sarah’s Bosom; now known as Port Ross. They were fortunate to find a whaler’s shelter, but a fire was crucial for their survival. To their dismay, they found only a single match between the lot of them, and a survivor put it in his hair to dry. The castaways piled dry brush between rocks, and they struck the only match as a matter of life and death. It flared, the fire burned, and kept burning for the next eighteen months. They were also fortunate to catch pigs and goats left on the island as emergency food for needy seafarers - for exactly their situation. They also added shellfish, birds, seal meat, and grew potatoes.

Although safe for the moment, their prospects were bleak. They were castaways in the brutal subantarctic with no more than the clothes they stood up in, and one man died in the freezing conditions. Nobody knew they were there, and there was little chance of being found by a passing ship. Nine months after the shipwreck, three men with the GENERAL GRANT’s chief officer, Bart Brown, tried to reach New Zealand. It was 290NM away, across one of the cruelest seas on the planet. They covered one of the small boats with seal skins and decided the mainland was heading east-north-east. Sadly, it was west-north-west, so they were never seen again. Eventually, in desperation, the ten surviving castaways made model boats and set them adrift carrying appeals for help. As it happened, one landed on Stewart Island months later, around the time the whaling-brig Amherst rescued the castaways. It had sailed close to Auckland Island purely by happenchance.

The ordeal was over, but the tragedy continued. The hold of GENERAL GRANT had gold worth around $4 million in today’s currency, plus private hoards of successful miners from the Victorian goldfields. In salvage attempts, a further eighteen people died, until in 1960, the New Zealand authorities banned any additional operations. After claiming 91 lives in total, GENERAL GRANT lies undisturbed in its sea-washed cave, most likely for all time.