Dinghy Cruising and the Backpack

In 1968 a former British Royal Marine, named Colin Fletcher, wrote and published a book about backpacking in the Grand Canyon.

That book, titled The Man Who Walked Through Time, described Fletcher’s experiences, observations and thoughts when, in 1963, he walked the entire length of that portion of the Grand Canyon contained within the 1963 boundaries of the Grand Canyon National Park. He was the first person to accomplish this feat, “all in one go.”

The Man Who Walked Through Time, along with his later book, The Complete Walker, earned Colin Fletcher the title of “spiritual godfather” of the wilderness backpacking movement—which is still very much with us, alive and well, today.

I have fond memories of reading Fletcher’s book and those memories re-surfaced when I decided to write about dinghy cruising, due to the many similarities shared between dinghy cruising and backpacking—not the least of which is the awareness of and the meaningful connection with, the Natural World.

We all pretty much understand the meaning of “a backpack,” also known as “a rucksack” and, in England as “a Bergen.”

But what, exactly, is “a dinghy”?

For the activity of dinghy cruising a dinghy is, emphatically, not the 8 to 10 foot tiny boat that is kept on the deck or in davits or towed behind a larger sailing vessel.

My definition of a “cruising dinghy” is a small boat having a minimum length of 12 feet (Wellsford SCAMP design), with the length going up to no more than 18 feet. Anything longer begins to be a “day sailer” or a “pocket cruiser.”

Like most definitions, these distinctions are sometimes found to be flexible.

Q. What does dinghy cruising have in common with Traditional Sail?

A. More than you might think.

I would argue that a cruising dinghy, as defined above, is not just a rich man’s toy or even the necessary auxiliary to a larger vessel. Many modern cruising dinghies are the present day versions of small working craft used by working people over many centuries. These boats were used for fishing, crabbing, oystering and for everyday transportation of goods, animals and people, back and forth across large bodies of water.

All these efforts required skills, knowledge, experience and good judgement on the part of the boatmen—and the boat women.

A great deal of that skill and experience has been lost. This is due, in my opinion, to the prevalence of outboard engines that allow inexperienced people to get behind the wheel of a “power boat” and drive off across the water, ignorant of the foundational concepts of seamanship and boat-handling.

Dinghy cruising, like backpacking, focuses on moving through the Natural World using small sailing craft. This requires a return to the skill set, knowledge and seamanship of earlier times; times without internal combustion engines that give a false sense of security and omnipotence.

Q. Why would anyone go to the trouble, effort and inconvenience of walking through the difficult terrain of the Grand Canyon when they could so easily drive an air conditioned car along paved roads, stopping at designated overlook sites?

A. Because walking “through it,” as opposed to just “looking at it” puts you in touch with, allows and encourages you to understand—or at least to begin to understand—and to become one with, the Natural World.

Nothing else can do that.

Colin Fletcher died in 2007 after a long and productive life and his legacy of awareness lives on.

The present day analog of Colin Fletcher, as an advocate of dinghy cruising, is another Englishman named Roger Barnes.

There are several other advocates and enthusiasts of dinghy cruising, but for the sake of brevity I have chosen to focus on Roger Barnes, who I do not know, because of his video presence on Youtube, the many places he travels to for dinghy cruising and the particular type of boat he cruises in.

The purpose of this posting is to outline and attempt to explain the beauty, utility, fun, relevance and historical connections involved with dinghy cruising. I will not try to examine the large number of boats and designs available for dinghy cruising.

However, I will briefly draw your attention to a few designers, a magazine and a very good small business dealing with equipment suitable for dinghy cruising.

The magazine is Small Craft Advisor. The business, which advertises in SCA is Duckworks.

My short list of designers of cruising dinghy includes Francois Vivier, a Frenchman whose designs are now available in the U.S.

(More on Vivier below). Another designer is John Wellsford, a very talented and prolific designer; see his Pathfinder and SCAMP designs. Then, John Harris, also prolific and talented, who does business as Chesapeake Light Craft, many of his designs are available in CNC kits and flat packs with all necessary materials.

There are also good cruising dinghy designs available from Michael Storer, Phil Bolger and Iain Oughtred. Others, some contemporary and others having “crossed the bar,” have designs available through Wooden Boat magazine and Small Craft Advisor.

As stated above I am focusing on Roger Barnes. Please go to Youtube and look for his entire series of videos entitled “The Dinghy Cruising Companion.” When you find it I think that it will make you curious and happy.

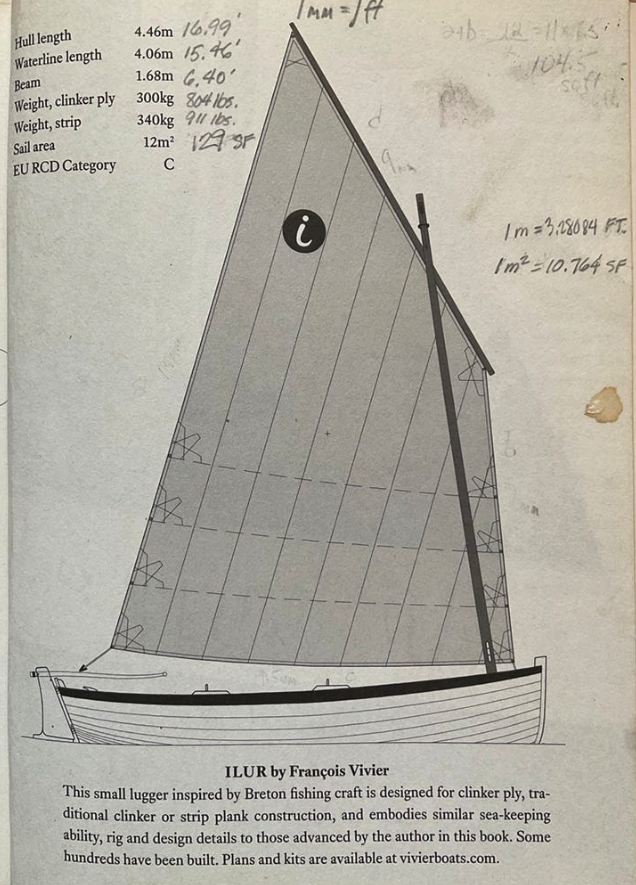

Barnes’ personal choice of a cruising dinghy (look for a separate video on his boat, which he bought in France) is a Francois Vivier design called ILLUR. This design is not a copy of any particular type of Breton small sailing craft, but its simple genius presents and incorporates traditional workboat design features that are important for cruising dinghy.

Relatively Small Size. The ILLUR design is 17 feet in overall length. This makes her big enough to sleep in-lying on an inflatable mattress on the floorboards. At the same time, she is small enough to be easily trailered behind a Toyota Corolla-size car, no need for a one ton dually pickup.

Spacious. ILLUR’s work boat ancestors had to carry 2 or 3 crewmen, nets, oars, anchors, extra cordage and, if lucky, large amounts of fish.

Stable, meaning well balanced, with a deep hull and a centerboard.The crewmen could stand up, walk forward to haul in the anchor, lower or raise the lug sail, and root around in the bilges for those tools that always end up down there.All of this was done without fear of capsizing or falling overboard.

Agile, refers to a combination of hull shape factors that allow the cruising dinghy to be rowed or sculled. If this doesn’t interest you it’s OK to use a small OB motor. Agility also refers to a hull shape that allows the boat to “take the ground”—meaning she is able to sit upright on her own bottom when the falling tide puts her on a mudbank. (Barnes illustrates and discusses the utility and convenience of this in several of his videos. Obviously, when you find yourself in this situation the seaman-like thing to do is to put the anchor into the mud bank and then walk down the beach to the boozer.)

Being spacious, stable and able to sit upright on the bottom all combine to enable you, the Captain, the Grand Poobah of your own, beautiful cruising dinghy to go places where larger vessels dare not go, for fear of running aground. This ability to explore creeks, bays and sloughs is generally known a “gunk holing.”

COST. Dinghies suitable for cruising such as ILLUR and her sister designs are not high dollar, hot rod racing dinghies, resplendent with fancy, complicated hardware, multi-colored cordage, hiking straps and Velcro.

They do not require large amounts of money to build, to buy, to refinish or to maintain. Nor do they require leasing a slip in an expensive marina—if you can find one. They will be perfectly safe, available and ready for use sitting on a trailer in your back yard, side yard, garage or drive way.

The neighbors will be curious and more than a little envious.

“The smaller the boat, the more often it is used.”

VERSATILITY. Because they are easily trailered, cruising dinghy scan go to windward at 60 MPH, i.e., travel wherever your car can pull them on a trailer. This allows you to go pretty much wherever you want—something you cannot easily do in a larger boat.

For example, you could trailer your dinghy, driving 1 or 2 hours, to the western shore of Lake Winipachuco, going to a public boat launch ramp, then rig her up, put her into the water and say goodbye to your spouse, friend, neighbour, sibling, etc., who will turn around and tow the now empty trailer to the eastern shore of the lake and leave it in the parking lot of the launch ramp there.

As you go out into the lake on your dinghy you are several miles and hours-or maybe even several days—away from your destination. But you are now on a “voyage of discovery”!

Your pre-voyage study of maps, charts, weather, etc. (just like Vasco da Gama) has revealed information about interesting places and things to see, places to avoid and places where you can trade with the natives for Moon pies, when necessary.

So off you go, on a small, manageable adventure where you can practice your skills, learn new ones-like gunk holing-and visit places that guys in plastic luxury yachts cannot enter.

If there is decent cell phone coverage you can call home, if you really want to.

In DINGHY CRUISING Part II I will review some ideas about equipment (simple is always best) and offer some thoughts on the virtue, elegance, power and practicality of the lug rig, especially the standing lug.

In closing, here is a quote from R.D. “Pete” Culler, master shipwright, craftsman, and boat designer of the old school. Pete said, “Experience starts when you begin.”

As always, all opinions and ideas expressed above are mine alone.

Duncan Blair

References:

Colin Fletcher biography on Wikipedia

Photos 1, 2 and 3: Sea-Boats, Oars and Sails, Conor O’Brien

Loadstar Books 2013, Originally published 1941