DUYFKEN- The Little Dove

With the DUYFKEN making appearance at the AWBF in February it seems like a great time to explore a little of her history thanks to Duncan Blair

DUYFKEN, Sailing free, with yards lowered on the hoists and sheets eased… “she doesn’t like flat sails.”

Many of us have watched brown pelicans gracefully skimming across the water, down low and almost touching the wave tops. Often, when they see or sense fish, they will fly upward to gain altitude and then dive straight down, crashing into the water, soon coming back to the surface with a beak full of fish and what looks like a smile on their faces.

That is a metaphor for this post. I plan to skim across the wave tops of oceanography, history, geography, mercantilism and the exploration of the Indian Ocean—ending up with a deep dive to go after some ideas and facts that I find to be interesting and useful.

Obviously, I am not an academic. I am a sort of shade-tree historian and anthropologist who enjoys the freedom to blog about what he thinks and share it with others, without any academic ambitions or illusions.

My purpose is to draw attention to some of the essential elements of sailing cargo trade routes of several hundred years ago, using the example of European powers in the Indian Ocean.

But first I need to acknowledge the contributions of two information sources. The first is the Australian sailor Alan Villiers (Born 1903–Died 1982. He went to sea at the age of 15.) I discovered his book Monsoon Seas almost a year ago and strongly recommend it (Monsoon Seas, Alan Villiers, 1952).

The second acknowledgement goes to Wooden Boat magazine, specifically a four-part series entitled “Replicas," published in 2003. The authors are William Gilkerson and Matthew P. Murphy. I became aware of the series about three years ago and obtained copies through the WB back issues office in Brooklin, Maine. I have returned to “Replicas” several time since then, sometimes sending copies to folks who I hoped would find them useful.

“Replicas” first made me aware of Duyfken, an authentic replica, right down to her trunnels, of a small, 16th century Dutch ship sent to the Indian Ocean in service to VOC, the Dutch East India Company. More on this later.

THE PORTUGUESE

The Muslim conquest of the land now known as Spain and Portugal began in the year 711 (the 8th century) and continued, ebbing and advancing, until the final years of the 15th century. Ironically and bitterly so, many of the descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese warriors who fought the Muslims went on themselves to “conquer” the peoples of the New World—taking religion and disease and bringing back gold and disease.

Henry (Enrique), Prince of Portugal, son of an English mother and son of King John of Portugal, brother to John’s heir, is known to history as Prince Henry the Navigator.

After military service against the Muslims Henry returned to Portugal, still a young man, to establish a famous school and library—a “think tank” for navigators, mariners, geographers, cartographers, and sea captains in Sagres, the extreme Southwest corner of Europe. He was reserved, taciturn and, most importantly, completely focused on expanding Portugal’s maritime exploration along the coast of West Africa and beyond: South, then East! His emphasis on gathering scholarly resources, information, facts and ideas about the world’s oceans was all the more important and interesting because at the same time that Henry was focusing on going South and East in order to get to the Indies, the Spanish and others were starting to seriously think about sending an expedition West, across the Atlantic, in order to find the Indies.

Henry’s progress was painfully slow; Villiers says of Henry that “His genius was constant in adversity.” His genius, as we now understand, was to conceive of “turning the flank” of Islam by attacking and taking away the economic foundations of trade with the Indies in order to bring those economic benefits to Portugal, thereby weakening Muslim control of Southern Europe.

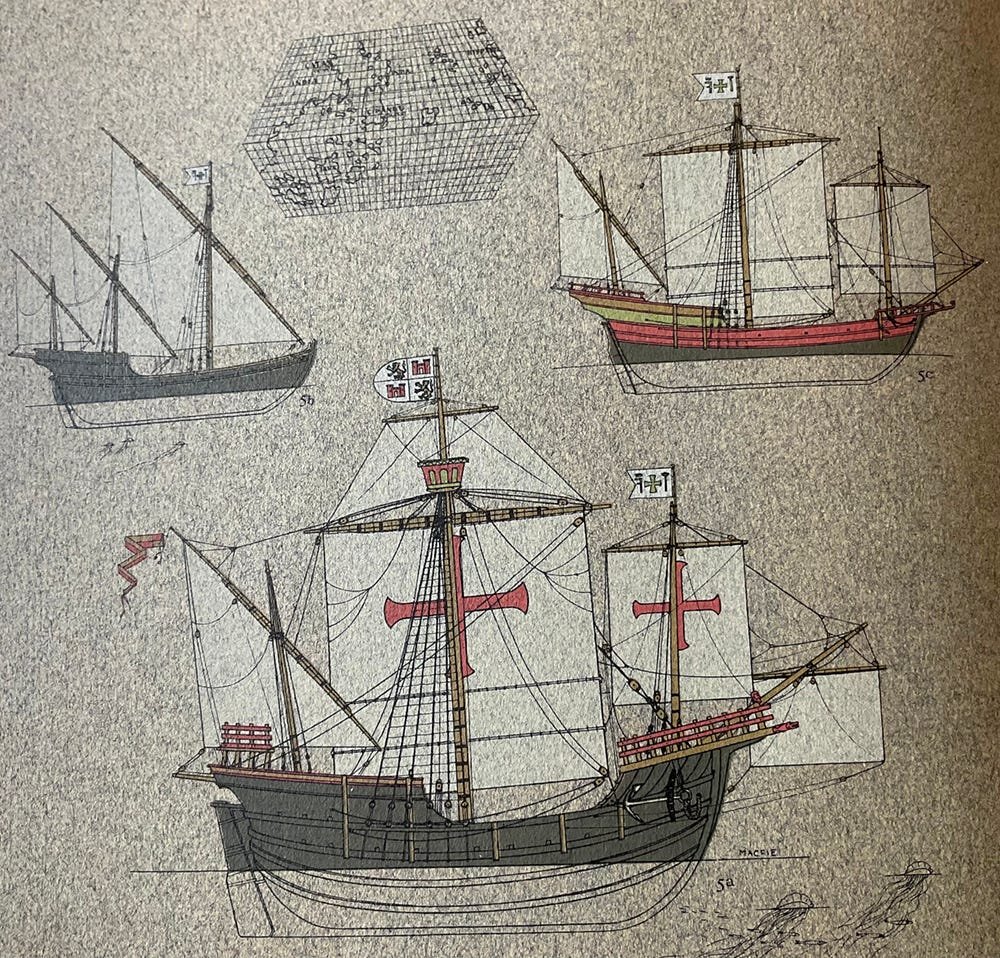

The first three ships of the Spanish expedition to the West left Spain in 1492, led by a Genoese sailor known to history as Cristobal Colon, aka Christopher Columbus. (See Illustration #1 Two caravels and a Nao.)

Two caravels and a NAO, 1492: Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria

Prince Henry continued to persevere, then, unfortunately, he died in 1460—unaware of Columbus’ voyage and discoveries. But what Henry had built in Sagres continued to function. Captains with familiar names such as Bartolomeo Dias, Alfonso d’Albuquerque and Vasco da Game continued to sail further south along the coast of West Africa, past the Bight of Benin and down as far as what is now called Namibia.

Part of Henry’s legacy was the development of the caravel ship design. He was not personally in the shipyard with an adze, measuring stick and string line but the research, information and experience of others that he caused to be gathered and analyzed at Sagres resulted in the new caravel design.

Caravels, not surprisingly, were carvel planked- edge to edge, with caulking in the seams. They proved to be stout and seaworthy.

Illustration #1 above shows two caravels—the two smaller ships and a Nao—the larger ship. Nao comes from the Latin “naves," meaning “ship." These three ships shown above are, in fact, the ships that Columbus had on his first voyage.

NINA—“the small one," has three masts, all with lateen sails—a style of sail brought to the Mediterranean centuries before Columbus and well known. Lateen sails are fore and aft sails which allow the ship to sail considerably closer to the wind than square sails.

PINTA ,“the painted one," has a lateen sail on her mizzen mast and square sails on her fore and main masts. This combination of lateen fore and aft sails with one or two larger square sails enabled the caravel, as a distinct type in both hull and rig, to take advantage of “leading winds,” coming from forward of midships as well as “fair winds” coming from abaft the midships line. This may all appear rather obvious today but 400 years ago it was a significant technological advancement, enabling the Portuguese mariners to widen their explorations beyond Africa and into the Indian Ocean.

The NAO shown is the Santa Maria.

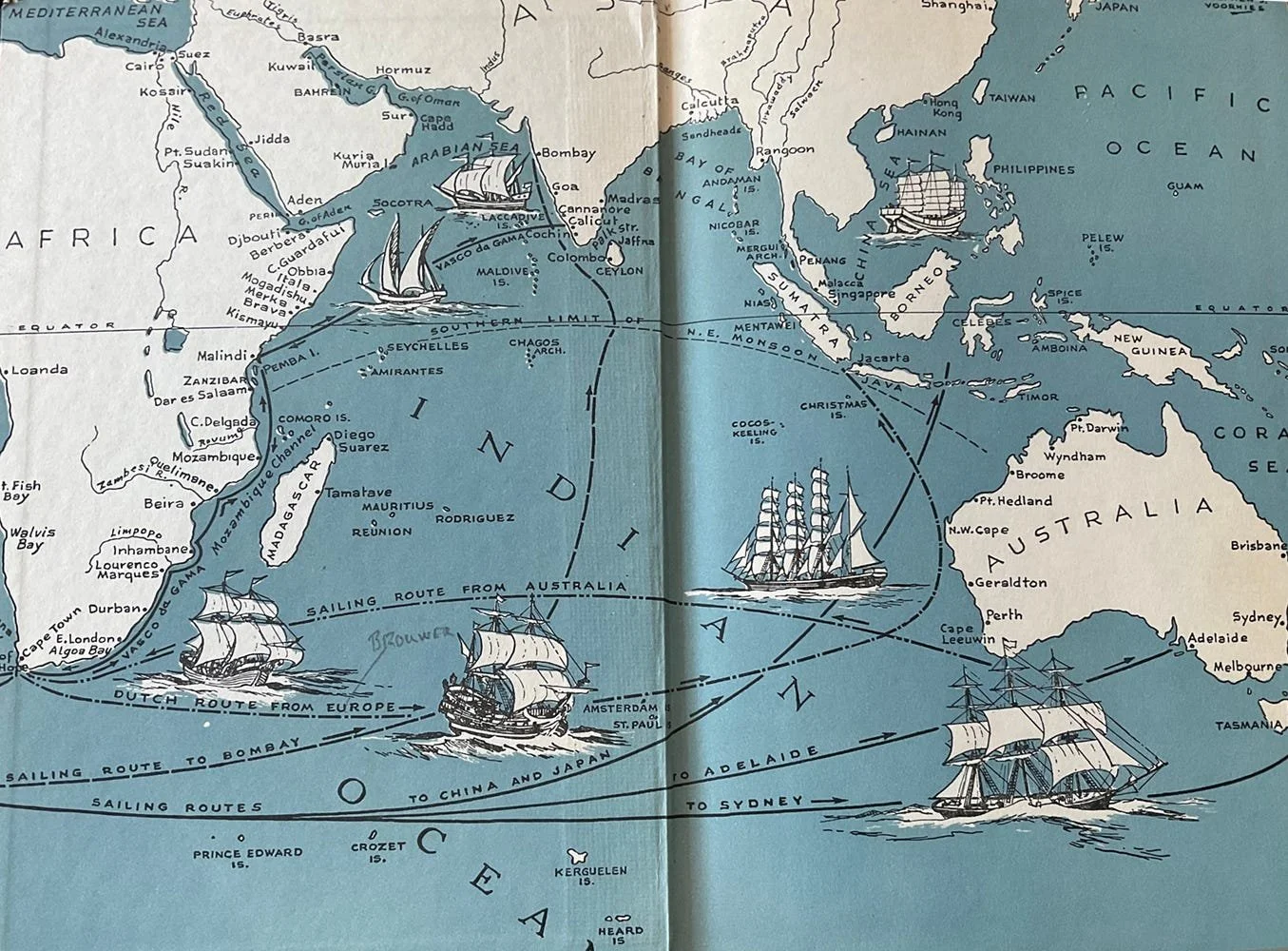

Villiers’ Map: Indian Ocean Trade Routes.

Illustration #2, above, is a simple map of the Indian Ocean taken from the inside cover of the book Monsoon Seas, written by Alan Villiers in 1952. (Disregard the clipper ships, they are not pertinent to this topic.)

The Cape of Good Hope, the southernmost point of Africa, is seen on the lower left. India is at 12 o’clock, upper center. Australia and Indonesia are on the right.

Villiers comments that “the wealth of the Islamic world relied not upon the trade and resources of Arabia, but upon control of the rich sea routes of the Indian Ocean. In Arabia there was little wealth upon which to found a world-dominating power.”

This is the crucial, factual reality upon which Henry the Navigator based his strategy of “turning the flank of Islam."

BARTOLOMEO DIAS

The last of the Portuguese seekers

Bartolomeo Dias made several voyages down the coast of West Africa before he was selected to command an expedition in 1487, 27 years after Prince Henry died.

Dias had under his command two caravels and a small store ship. Upon reaching Walvis Bay in what is now Namibia, Dias left the store ship and continued sailing South with the two caravels for 13 days.

Then he turned East, with a strong Westerly wind pushing his caravels along “fast as small albatrosses.”But his crews rebelled; they were tired, hungry, and frightened by being where no Portuguese mariners had ever gone before. They begged Dias to go North, so he did, possibly having a better understanding of where they were than the crews did.

The two caravels made landfall in what today is known as Mossel Bay, East of Cape Alguhas, which is itself East of the Cape of Good Hope, and clearly located in the Indian Ocean. Bartolomeo Dias, Portuguese mariner, ship captain and explorer had turned the flank of Islam.

His two ships turned around and sailed back North, back to Portugal.

Dias was later selected to command a ship on another expedition around the Cape of Good Hope under the leadership of Cabral. As their ships approached the Cape Dias’s ship was struck by “a great squall” and it sank, never to be seen again.

To this day there is no known portrait, drawing or “likeness” of Bartolomeo Dias- but his achievements are not forgotten.

VASCO da GAMA,1498

In 1498, just six years after Columbus’ first voyage, Vasco da Game led an expedition to the Indies that, for the first time in the history of Portuguese exploration, was motivated more by trade than by discovery. After several reverses and considerable adversity, including scurvy and the death of his brother who had accompanied him, da Gama returned in triumph to Portugal in the last month of 1499.

The cargo holds of his ships contained spices, ivory, silk cloth and delicate porcelain to grace the tables of wealthy aristocrats. Villiers characterized da Gama’s achievement with this statement—“He had sailed 24,000 miles to make the greatest voyage then known to history. Columbus was also in quest of the Indies but it was da Gama who found them.”

Once found, the trade routes were forced open by the Portuguese who established new trading centers, some of them listed below. Also see Villiers’ map of the Indian Ocean.

LOCATION, DATE ESTABLISHED

GOA, West Coast of India, 1510

MALLACA, N of Singapore, on West coast of Malay Peninsula, 1511

MACAU, Adjacent to Hong Kong, 1554

With the passage of time the Portuguese commercial empire in the Indies and what is now known as Indonesia expanded and prospered, reaching as far North and East as the coast of China. Then, like all empires, it weakened and eventually collapsed, to be followed by another, even more aggressive maritime power.

DUYFKEN off Banda, Indonesia, doing 8 kts

THE DUTCH

Mercantilism takes hold.

MERCANTILISM: An economic practice by which governments used their economies to augment state power at the expense of other countries.

In 1600 the British East India Company, nick-named John Company, was founded. It lasted until 1874.

In 1602, in Holland, the Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (United Dutch East India Company), hereinafter referred to as VOC, was founded. VOC lasted until 1875.

If you trust Wikipedia, which I do not, you might be interested in their statement that VOC is believed to be the largest company to have ever existed in recorded history.

VOC’s efforts were spread out over tens of thousands of miles of uncharted ocean. Their base was the city of Batavia, present day Jakarta, now in Indonesia, formerly called Java.

In 1611 a VOC sea captain named Henrik Brouwer pioneered what was to become the Dutch preferred route from Holland to Southeast Asia. It is known as the Brouwer Route. It is an interesting example of the boldness and ability of the Dutch seamen who grew up and learned their trade in the cold, stormy waters of the North Sea herring fishery.

It is deceptively simple. From Amsterdam, Holland, you sail South, all the way to the Cape of Good Hope, then you go still further South to approximately 40 degrees South Latitude. (16th century mariners knew how to find Latitude and had the appropriate tools to do so. Longitude was the challenge that would be solved in the 18th century with the invention of the chronometer.) Once at 40 degrees South you turn East. You are in, or at the very least on, the edge of the Roaring Forties, famous for their reliable and very strong Westerly winds and the big seas that they create. So you hitch up your trousers, tighten your belt, say a prayer to Neptune and run before, “sailing large," the Westerlies, going Eastward almost to the coast of Western Australia. Then you assure the crew that everything is good and decisively turn North, with just a wee bit of West, until you come to Java and Batavia, Simple!

I have no information on the route used to sail back to Holland.

Villiers says that one Dutch captain sailed back to Holland from Java by crossing the South Pacific, going East—about Cape Horn through the Straits of Magellan, then up and across the South Atlantic to the English Channel, North Sea and home to Amsterdam. Simply Amazing!

So, strong, capable ships, square sails and favourable winds being intelligently used by experienced and bold seamen who understood and trusted the simple utility of working with the winds that were available.

DUYFKEN fully rigged with working sail. Sprit sail beneath bowsprit.

Duyfken (See Replica of her in waters off Australia above).

Duyfken—Little Dove—was an actual VOC ship, 80 feet long, shoal draft and carvel planked. She had three masts and a total of six working sails, lateen mizzen, square sails on fore and main masts and what was known as a sprit sail flown under the bow sprit.She was fast, sturdy and had a relatively small crew of 20.

Her design was a “jacht," which in 16th century Holland meant “hunter” or “persuer." Her rig was that of a “pollaca.” [Pollaca or Polacre rig—A square rig of the Eastern Mediterranean in which the lower mast, topmast and topgallant are made of a single spar, the upper yards being lowered all the way to the deck for furling. Note: emphasis is mine and will be referred to later.]

She was built in Holland in 1595, before the start-up of VOC. She had sailed to Java in 1601 and was purchased there by VOC in 1603, then sailed back to Amsterdam. On that return voyage to Amsterdam, off the Southern tip of Africa ,close to where Dias’ ship had disappeared, Duyfken became separated from the other ships in the convoy and went on alone. She arrived in Holland two months before the other ships.

For hundreds of years there had been stories and legends floating around Europe about a mythical land mass somewhere in the Great Southern Ocean. It was referred to by scholars as “Terra Australis Incognita," but no European had ever actually been there.

When Duyfken left Bantam in the Java Sea she sailed South East across the Timor Sea, then across the Arafura Sea to a point of land now known as Cape York Peninsula—the southern side of what is now known as the Torres Strait. Duyfken’s captain, Henrik Jantzoon accurately surveyed and mapped a piece of the shoreline. By getting there in 1606, surveying and mapping, Jantzoon became the first European to “discover” Australia, the mythical land mass of the legends, and Duyfken had the honor to be the first European ship to go to Australia.

This historic event, this “discovery,” took place 164 years before Captain James Cook, R.N., on the ship Endeavor, “discovered” the North East coast of Australia in 1770 and claimed it for Great Britain, under whose rule it went on to become a notorious penal colony.

Alan Villiers, himself an Australian, says that to the Dutch mariners the continent of Australia was “nothing more than a navigational hazard” because they were so focused on the rich trade opportunities to be found in the Indies. In 1606, still in Australia, Duyfken suffered hull damage when she ran aground on a reef. The local VOC shipwright judged her to be “unrepairable.”

But, after several centuries, she was re-born.

DUYFKEN below decks, looking forward. “Bricks” are lead ingots for ballast.

Duyfken below decks, looking forward. “Bricks” are lead ingots for ballast.

For the rest of this post the name Duyfken will refer to the new, replica version.

REPLICA, DONE VERY WELL

Captain Cook’s famous ship, Endeavor, started her life in England hauling coal from Northumbria to London. She was commissioned into the Royal Navy and used by Cook for his several long voyages of discovery across the Pacific Ocean. A replica of Endeavor was built in Australia over several years, ending with her launching in 1993.

Supporters of the Endeavor replica, having assembled an outstanding team of shipwrights, riggers, caulkers and sail makers, began looking for another project.

What developed was a well structured, well conceived and well funded effort (not always the case with Replica projects), aimed at building a replica of Duyfken, whose story was known by marine historians and archaeologists, if not by most Australians.

(For observations on the politics and funding dynamics of replicas of traditional sailing vessels see my post on this site entitled “Why Some Boats are Honored and Others are Not," 14 April, 2022.)

Their efforts were successful; Duyfken was replicated, very carefully and very well. There were never any plans for her or even for her namesake. Her shape came from the mind, heart and experience of her original builder.

Pretty much the same can be said for the replica. Historical research, comparisons and a technology called Multivariate morphometric analysis of iconography was used “to project data into multi-dimensional space.” This is one of the many reasons I am happy not being an academic.

All this makes the process of replication of Duyfken sound more reductionist than it was. With the combined knowledge and experience from building wooden ships the shipwrights used wood(from the forests of Latvia),heat, spikes, trunnels, clamps and levers to form a hull that was historically correct, had sweet lines and was wholly reflective of the techniques of Dutch ship building in the 16th century. You could not ask for anything better.

Her 21st century captain said that “she sails like a bird.”

DUYFKEN top sails furled. Wind blowing Force 7

It is worth noting that Dufyken’s rigging, standing and running, is all hemp. Her sails are hand sewn and made of flax. Best of all, she is steered with a whip staff.

It is tempting to launch into my own analysis of her sailing ability, but that would be extremely presumptuous. I will, however, strongly suggest that you look at the many YouTube videos, and even better, get a copy of the book, To Build A Ship: The VOC Replica Duyfken. Author and photographer, Robert Garvey.

The text is good and the photos are outstanding. It can be found on Amazon and ABE. My new copy cost $27.

I find Duyfken to be both important and useful. Useful as a “time machine," taking us back much farther in time than most functional examples of Traditional Sail that exist today. Her importance lies in the fact that her presence as an artifact of experimental archaeology allows people to learn and understand how things were done; how sails were raised and lowered on a polacre rig, how an 80 foot long vessel was steered with a whip staff and how vast oceans were regularly crossed by what seem to us to be primitive vessels.

“There are more things on Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Duyfken, small as she is, also demonstrates a surprising turn of speed.

The fact that she does not have a lofty pyramid of sails and fiddle-string tight wire rope rigging makes her, to me at least, more approachable, relate-able, and friendly—small enough to comprehend.

Her size and 16th century atmosphere make her all the more impressive when you learn her history of crossing the Great Southern Ocean, the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel, not to mention the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. And she did all that with the rig you see on her today, without radar, electronics or an engine.

There are clearly useful lessons to be learned from the Little Dove.

DUYFKEN “Sailing like a bird”