MAORI LASS- “It just feels like a different world”

By Chris Crerar

When a 21-year-old Jan Tabler told her parents that she and her husband Jim were planning to set sail from Sydney to the USA on their 30-foot timber sloop, Maori Lass, they were so worried they purchased a brand new Bukh engine as a parting gift.

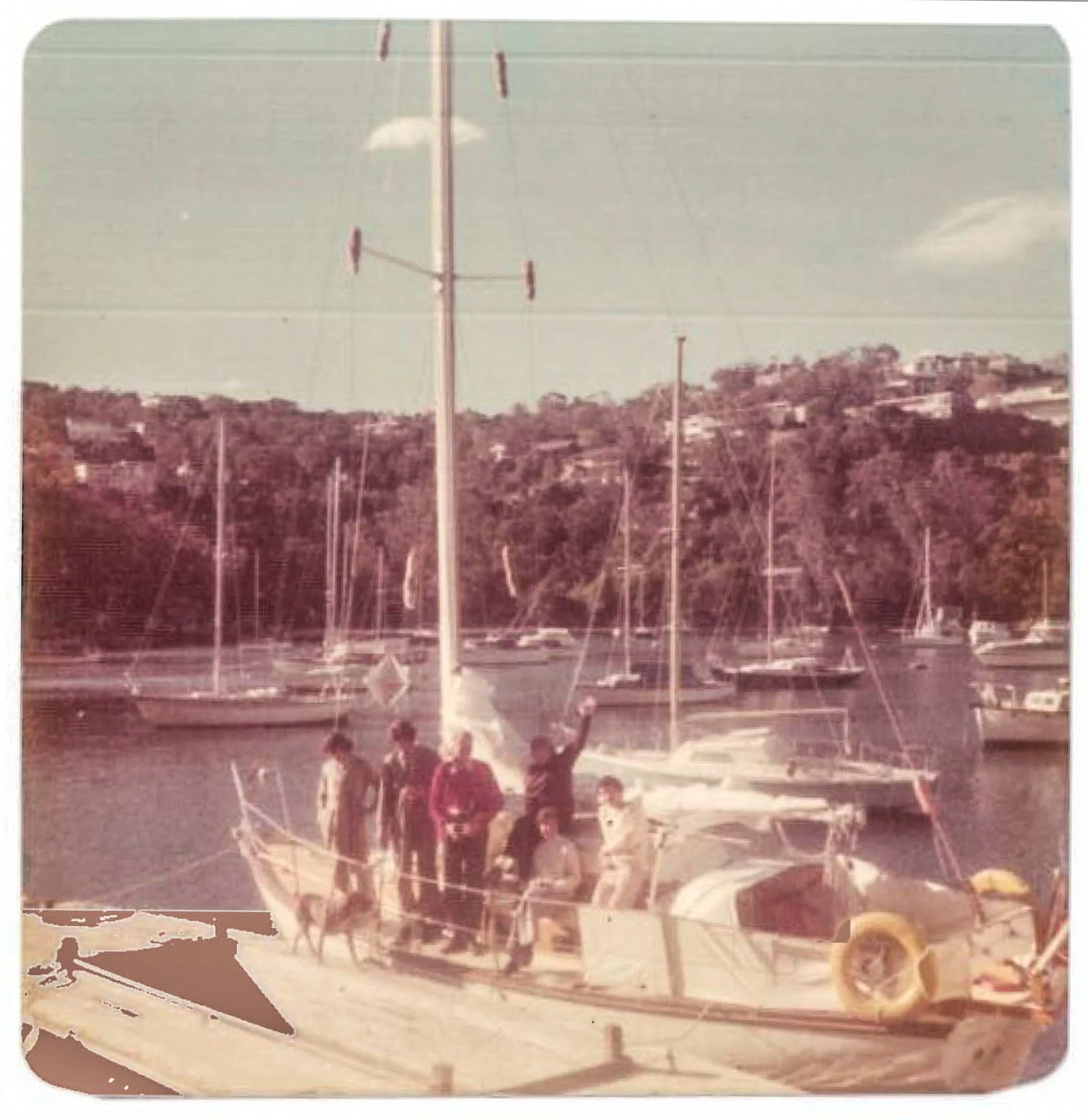

Leaving Castlecrag, Sydney, 11th July 1975

“My parents were mortified”, says Jan.

“That’s why we got an engine. They couldn’t see their darling daughter going out of the heads without an engine”.

“Dad loved fishing from a tinnie. Mum hated the water and couldn’t swim. It was against what they thought was a suitable thing for me to do”, Jan laughs.

Despite the high probability of causing sleepless nights for her parents, Jan and Jim threw off the lines at Castlecrag in July 1975, before a large gathering of family and friends, and set sail through the Sydney Heads, and north up the East Coast. They wouldn’t sail back into Sydney Harbour until November 1982.

As the latest custodian of Māori Lass, I’ve often tried to visualise the people who’ve sailed her before us, the far-flung corners of the world she’s been to and the rough weather she’s survived. Rounding the buoys in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel during twilight racing with the Kettering Yacht Club just doesn’t seem a suitable enough challenge for her. But each time the conditions have become hectic, Māori Lass has risen to the occasion, creating an unfolding realisation of her confidence instilling capabilities.

So, when SWS’ Mark Chew forwarded on an email from Jan asking if they knew where Māori Lass was now, I jumped on the chance to speak with her. I could see from Jan’s email to SWS that she was quite a character.

Referring to a Woman’s Weekly article published about their journey, Jan wrote, “It is rather inaccurate, you can’t sail to Mogadishu. And the comments about task sharing and our different roles on the boat are very sexist and frankly it is embarrassing. But it was fun to see Christine’s reactions to being on a small yacht”.

Now living in Gympie in the hinterlands of Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, Jan and I spoke for an hour and a half. Many gaps were filled, and incredible tales told, all through the lens of fondness for the little yacht that was home and a portal to the world for 6 years of Jan’s early adulthood.

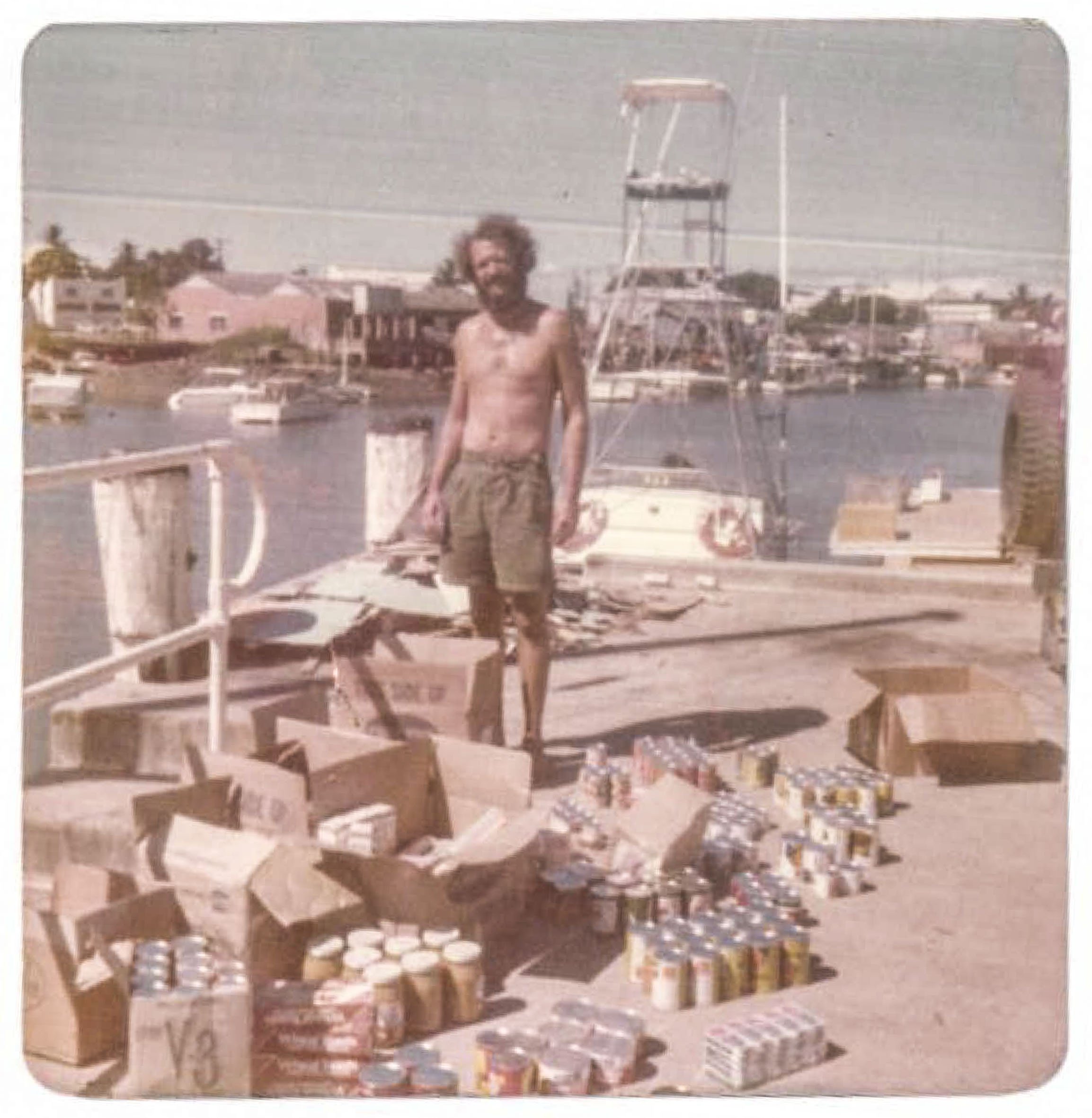

Townsville, sorting provisions to stack aboard. September 1975

Built by former New Zealander Ron Andrewartha and his family in the backyard of their North Hobart home in 1949-50, Māori Lass, was designed by another Kiwi, H.E Cox for a Christchurch businessman.

The design was published in the March-April 1947 edition of Seacraft magazine, and this is where Ron picked it up. Built with the classic Tasmanian combination of blue gum frames and celery top pine planking, the Andrewartha family were renowned backyard boat builders and sailors. Launched on the 15th September 1950 by a steam crane on Hobart’s waterfront, she was a club racer on the Derwent until 1970, when she was purchased by Port Hacking’s Chris Small and sailed to NSW.

When Jan and Jim found Māori Lass for sale in 1974, she’d passed through a couple more hands and was in a sorry state. Rotting decks meant that nobody wanted to buy her, and they picked her up for a song.

“Because the deck was leaking, the ply below it had delaminated and was hanging in strings. It was pretty horrific”, Jan says. “Nobody wanted to buy it because it looked so bad”.

“This will knock your socks off… when we bought it, we used to sleep in green garbage bags”, she laughs, adding that they only slept in them when it was raining.

They spent the next two years living on Māori Lass on a swing mooring at Castlecrag, working to save money and preparing her to sail back to Jim’s hometown of Corpus Christi on the coast of Texas.

While it’s not an activity that springs to mind when you think of Texas, Jim grew up sailing there and was experienced in seamanship and navigation. He built on his maritime knowledge and skills when he served as a submariner with the U.S Navy. He’d come to Australia to go ‘ranching’, or droving, but the lure of the sea and meeting Jan kept him on the coast.

“He really knew what he was talking about as far as sailing and navigation went”, says Jan.

Preparing for the trip, the pair read “masses of books”, all of which Jan still has.

They talked to yachties around Castlecrag and even hitch-hiked to Hobart for the finish of the Sydney to Hobart.

“We hitch-hiked down and took our sleeping bags. We slept in them on the finish line until they finished in the middle of the night. A couple of the organisers saw us sleeping there and said ‘oh, you must be very keen, come back for breakfast’. So, we went and met some of the racegoers”, Jan says.

A chance meeting back in Sydney with an around the world sailor from the USA helped them kit out Māori Lass for the journey.

“He was sailing on a beautiful big Scottish boat called the Ron of Argyle. All his companions had left as he was a bit notorious for shouting, and he came into Sydney alone”, remembers Jan.

“Whatever you want on my boat, I’ll sell it to you for a reasonable amount, he said. We showed him our bank account and he said ‘Oh my god”, says Jan.

“We came away with a life raft, bronze rigging bits, lanterns and a beautiful antique sextant”, says Jan. “And he got our bank account”.

Finally ready to depart, it was a rough trip up the east coast before they sailed across the Gulf of Carpentaria to Gove.

“We were going to go directly from Gove to South Africa, but I got really sick, so Jim decided the closest place we could go was Bali. We had no detailed charts or anything. We just winged it”, she says.

Bali .Officials checking our paperwork. July 1976

Also, without any paperwork to enter Indonesia, Jim feared the worst. He called his father back in the USA. Jim’s dad was a gynaecologist who happened to have once delivered a child of Henry Kissinger’s wife. With all the analogue speed of the 1970s, they soon had special access stamps in their passports.

“We got passports with a lot of good stamps. We could virtually go anywhere and do anything”, Jan says.

Their stay in Bali sowed a seed for a different kind of journey, Jan says.

“I really liked the people”.

“When we started out, Jim just wanted to do the big passages and get there quickly, but he came around to my way of thinking. That the people are what it’s all about really”.

Needing to re-group and raise some funds, they returned to Australia, settling in Darwin and staying for around a year.

Refit finished in Darwin at Dinah Beach July 1976

Much work was completed on Māori Lass during their Darwin stay, preparing the boat for whatever lay ahead. Suspect about the condition of the original timber mast, they swapped it for a car and installed the boat’s first aluminium mast.

Darwin. Delivering the new mast from the wharf to Dinah Beach November 1976

In November 1976, they set off once again, this time to island hop through Indonesia and further up into Southeast Asia, Jan was writing letters to later send home that surely would have kept her parents up at night.

From her Darwin to Singapore letter, dated September 1978, Jan wrote, “The wind that night blew even more, and the boat was going so fast she was surfing down the waves. The way to slow her down was tow a rope with a full plastic fuel container. We were pulling two of these that night and it did help to steady her down and the steering was ok. We kept having those unexpected baths though and were tucked up in our wet weather gear and tied to the cockpit. It’s a pity we didn’t have much moon as it would have helped.”

With their self-steering system not working from the outset of their journey, Jan and Jim were compelled to take turns in keeping watch. Their system of 4-hour watch rotations would frustratingly stay in place, despite attempts to repair the mechanism, until a replacement was kindly provided by Jim’s Great Aunt after they arrived in Corpus Christi.

Picking their way through the Indonesian archipelago, Jan’s letters home vividly capture another time. Her stories tell of the simple, traditional lives of local people. Of stilt villages over water, fishing fleets heading out at night and being tailed by fascinated children everywhere they went.

Jan says that Māori Lass’ modest size helped them connect with locals wherever they went.

“Because we’re on a small boat, they had something to relate to us. We weren’t just tourists coming”, she recounts.

“It all started because of Indonesia. The people were just wonderful. A little group of fishermen would always come out and hang off the boat”.

Without a depth sounder and limited charts, they would often anchor well off the shore, then later cautiously venture closer inshore to anchor near a village.

“You needed someone on the boat to let others know it wasn’t a free for all. And I can sharpen knives really well. We had this big knife collection and Jim would say, ‘now I’ve got to go to town just sit on the deck and sharpen knives. It made everyone really cautious, and I can now sharpen knives really well”, Jan says.

“It had to be, there weren’t any regrets about it, it just had to be. To make sure the boat was there when we returned, and we could continue with our journey”.

Jan says they followed this rule almost everywhere, but it curtailed their freedom to explore many of the places they were visiting together.

“We had very little stuff stolen as one of us was always with the boat. So, it was a tie”.

As Jan and Jim sailed north, they enjoyed extended stopovers on the Javanese island of Madura, Singapore at the Changi Yacht Club and Georgetown in Penang, where they spent considerable time repairing the Bukh, as it was literally shaking itself to pieces.

Day sailing off Changi, Singapore

In her letters home from this leg of the journey, Jan describes places yet to be altered by modernity, colonial grandeur and decay, filthy harbours, anthropologists studying village life, exotic food, and market life. Her descriptions are wonderfully evocative, making me wish I could press rewind and join them there on Māori Lass.

A close encounter with a group of armed and menacing Thai men, possibly pirates, off some small islands on the Malaysian-Thailand border reminded them that not everyone has your best interests at heart. Watched over by the machine gun wielding wannabe pirates, Jan and Jim were able to make their escape when a passing patrol boat rattled and distracted the Thais.

“We felt very fortunate that we got away from them because we knew there were pirates in the area”, says Jan.

A week of beautiful sailing north further embedded the rhythm of their days at sea.

“We did have a rhythm that we understood. I did the cooking and cleaning up. We did our four our watches. Jim was responsible for the navigation. We were on deck if we needed to do any sail handling. The sailing decisions were up to Jim, because he had all the experience.

I did a lot of sail repairs because we had really bad sails, while Jim did a lot of other repairs”, Jan says.

Navigating by sextant, listening to the BBC World Service, drinking “gallons of coffee and tea”, flying fish whipping by, and sunny, warm weather all combined to bring a dreaminess to this passage.

The historic port town of Galle in Sri Lanka was the next stopover, and an extended one it became. Staying at the colonial home of Don Windsor, with its sweeping verandas, and dining there at night with other visiting sailors, Jan and Jim were beguiled by Galle and the people.

With the sheltered port of Galle and skilled labour on hand, Māori Lass received some much-needed attention.

“The bottom needs painting and so does the interior. Labour here is $2 US a day here, so you can guess who’s not going to do the work on the boat for a change”, Jan wrote in a letter home.

She says that Don Windsor went out of his way to assist visiting sailors.

“He set up tradesmen to come down to your boat, to do whatever you wanted, whether you wanted something painted or carved. He had this little team of workers who would do a fantastic job for very little money”.

Falling under the spell of Sri Lanka saw them, and others, stay longer than expected. The approaching “no wind monsoon” season hastened all their departures west to Africa or the Maldives.

Jan and Jim headed straight for Djibouti and back to 4-hour watches.

“As with previous lengthy sails, we’ve developed a routine of sleeping, working, and steering. That ‘blessed’ self-steering has become the most useless article on the boat next to my evening dress”, Jan wrote.

Reading Jan’s letters home, they were clearly charmed by the French African atmosphere in Djibouti. They dined out under a starry night at a rustic local restaurant and admired the colourful gowns of tall Somali women contrasting against the dusty, glarey townscape.

Djibouti 1979. At anchor with Portuguese navy sail trading vessel Sabres

From there, they sailed to Hodeida in Yemen. Jan describes Hodeida as an exotic, friendly and colourful place that I can barely picture in my mind. Having travelled extensively in Southeast and South Asia, I could conjure images of Jan and Jim’s experiences travelling through Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka, but Africa and the Middle East remain exotic and other worldly in my mind. Thinking of the conflicts that have since wracked countries such as Yemen and Sudan, I can’t help thinking they were so lucky to visit when they did.

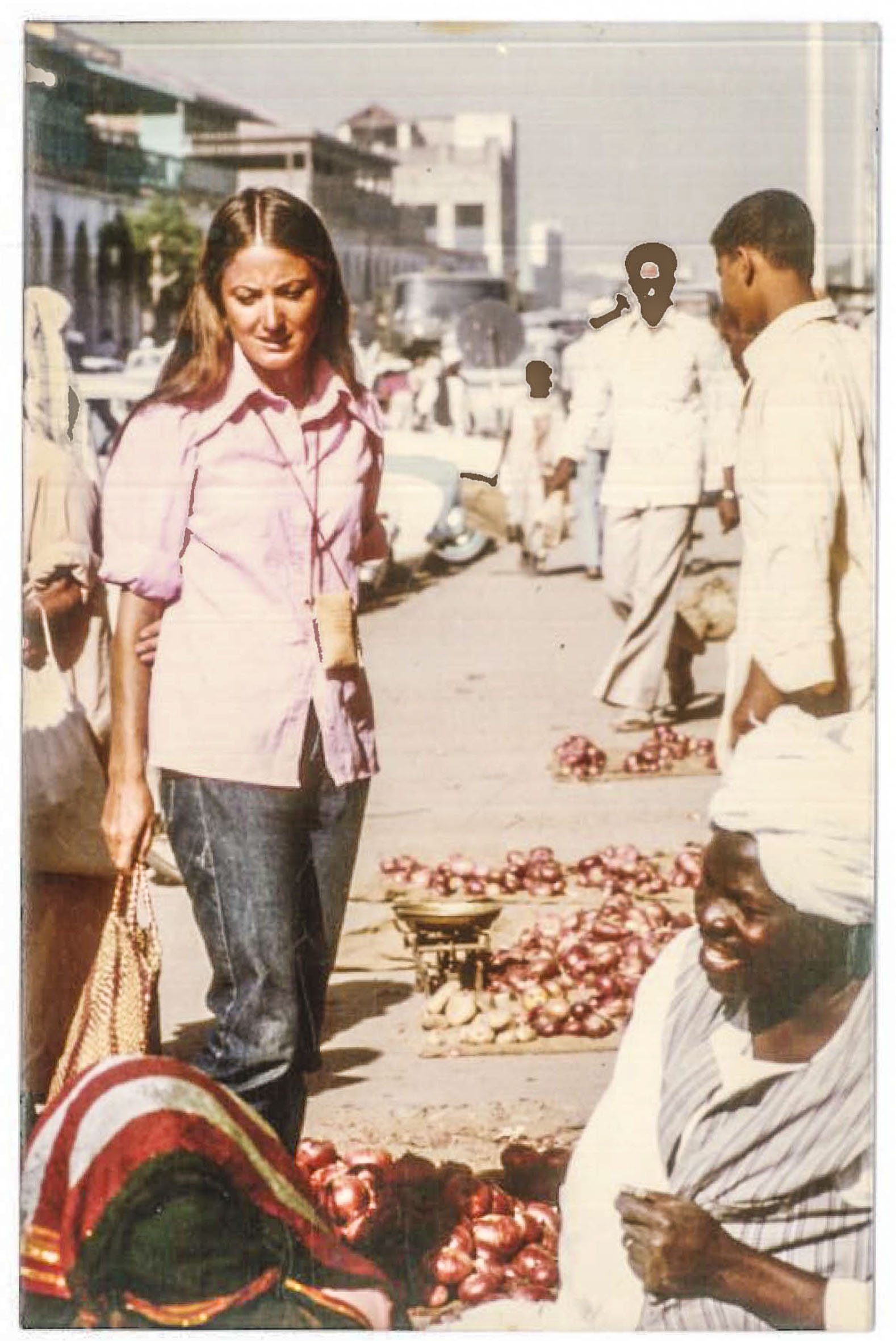

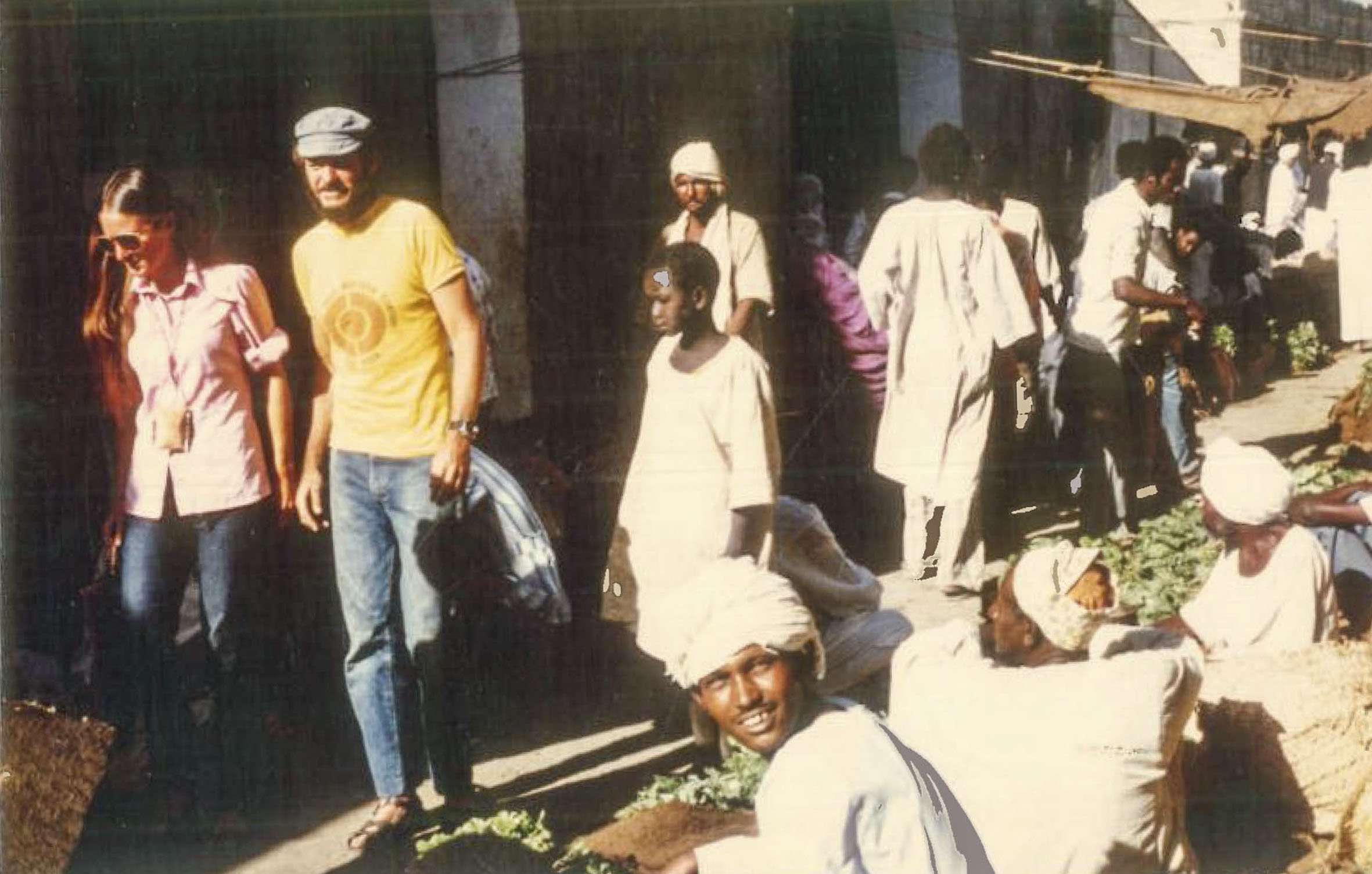

Port Sudan . Shopping for fresh food supplies at a street market.

Sitting in a café one day in Port Sudan, Jan and Jim met and Australian woman, who happened to be an Australian Woman’s Weekly journalist.

“The reporter Christine Osborne had been sent to Port Sudan to report on the refugee crisis and was being shown a false refugee situation and escorted to select locations. Christine thought that she wasn’t seeing the truth. Frustrated and tired she saw us sitting in a sidewalk cafe and stopped to say hi. At that moment she decided to switch her reporting mission and write about Māori Lass instead”, Jan says.

Port Sudan. Shopping for fresh food supplies at a street market.

Jan remains frustrated about the focus of Christine’s article and wrote at the time, “We both felt she missed the main ideas behind boat living and travelling. Her thinking and ours was different and we could not change her views. For example, she only wanted to know about the rough sea, action type things and what we felt deprived of on the boat. She didn’t think to consider how we cope from day to day to overcome (her) so-called deprivations”.

Reading the article, I see Jan’s frustrations, right from the opening paragraph.

“Weapons? We carry a .44 magnum. If people get impertinent, Jim takes it out and sits cleaning it on deck. But being a small timber boat, Māori Lass attracts little attention – it’s the super-flash yachts that get into trouble”, Jan was misquoted as saying.

Travelling through the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, Jan and Jim enjoyed many instances of warm hospitality from the crews of tankers and other commercial ships, both Australian and other nationalities.

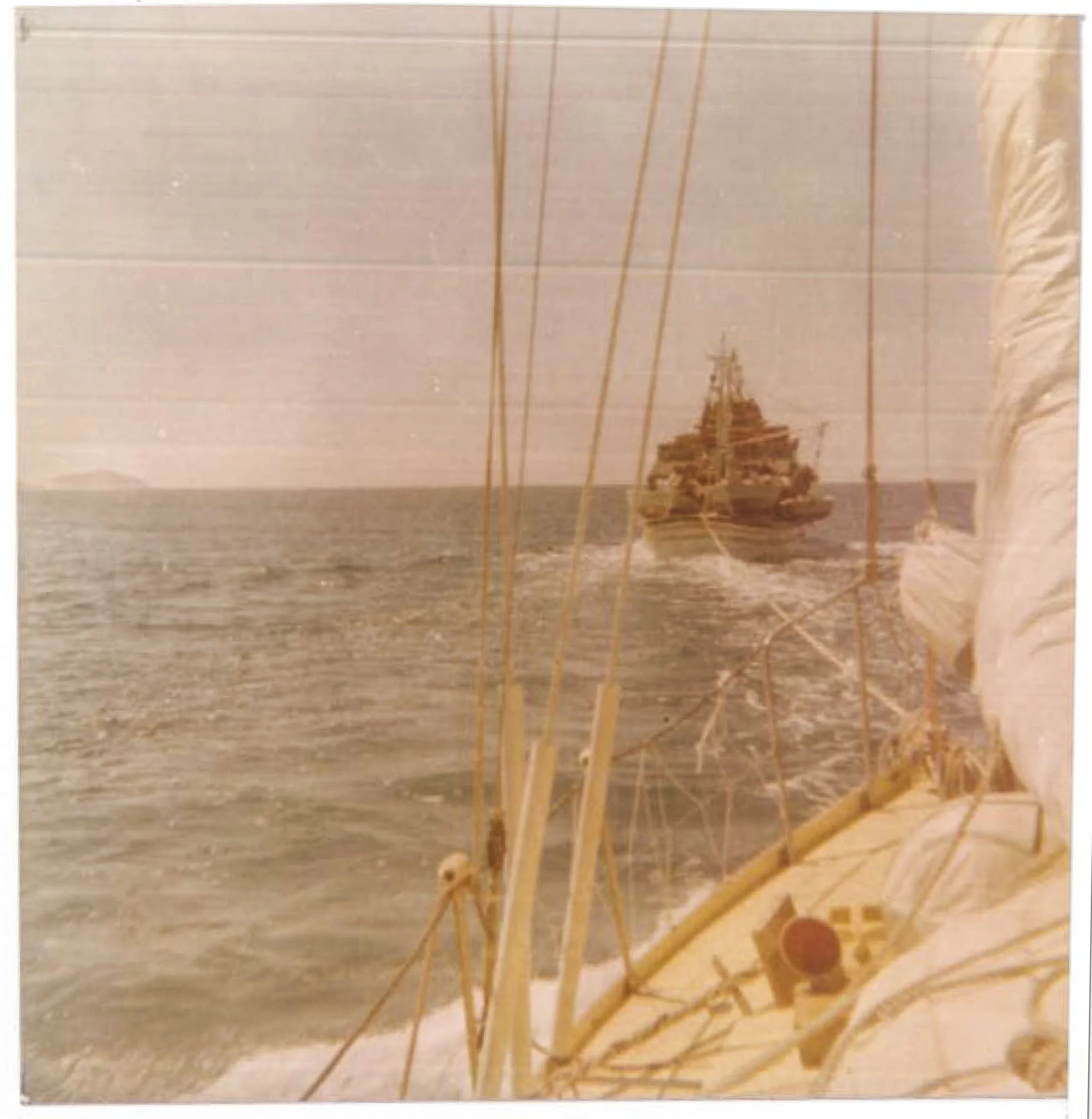

Egyptian fishing boat towing MAORI LASS to Suez. June 1979

“I’m overwhelmed by the generosity of the ships. One gave us water. Another Italian crew contributed to two yachts 10 frozen chickens, 300 eggs, fly spray, dishtowels, washcloths etc. We are madly trying to get through all the eggs. It’s funny that we went from none to plenty, costly to free in such a short space of time”, Jan wrote.

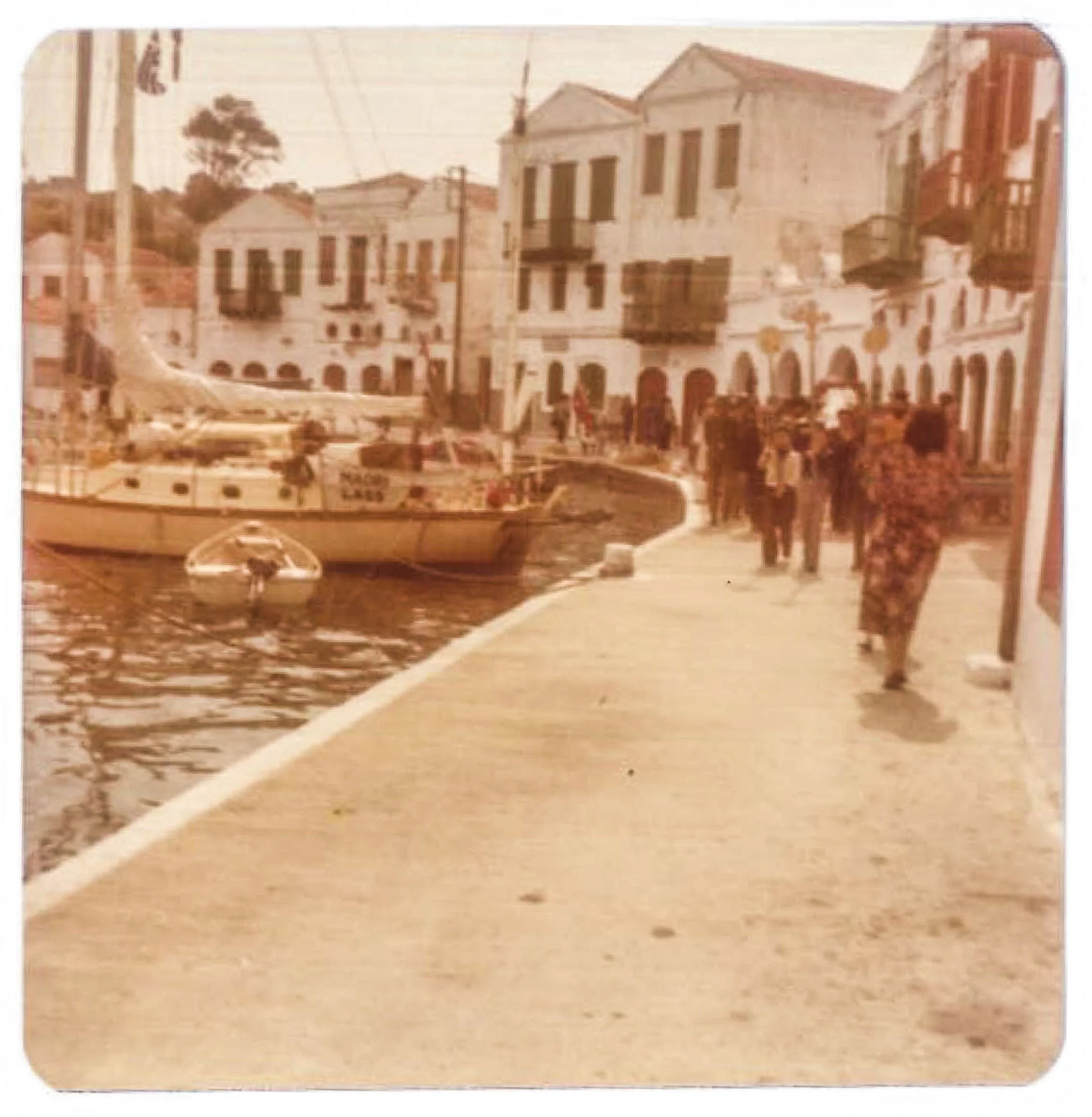

Kastellorizou, Greece

To keep your interest in continuing to read Jan’s story, and to stop it blowing out into becoming a book, I’ll condense their travels though the Red Sea, Suez Canal, Mediterranean and across the Atlantic. In fact, lets join them after their 22-day crossing of the Atlantic in the Caribbean.

Although the Caribbean in Jan’s letters to home sounds tropically idyllic, as we might all be able to imagine, she says that some incorrect paperwork meant that she was literally a “prisoner” and they had to stay and work in St Thomas in the Virgin Islands until the correct paperwork came through. In this era of instant messaging and electronic document transfers, it seems unthinkable that this took 3 months back in the 1970s.

Once the correct paperwork was in place, Jan and Jim were ready to depart for what was meant to be the final leg of their journey – across the Gulf of Mexico to Jim’s hometown of Corpus Christi on the coast of Texas.

Encountering a huge storm on their night-time approach to Corpus Christi, Jan wrote “I have never been so frightened”. Like a magnet drawing Jim home, the storm was pushing them towards the lee shore. Being pushed by 55 knots gales and surfing steep pitching waves, Jan and Jim had no choice but to “make a break for the shore”, despite the lead lights in the channel being out and no answer from port authorities on the radio.

Corpus Christi, Texas 1981

“We were absolutely exhausted when we got into the channel, and we didn’t get very far. The lead light was out, and we ran up into the mud on the side of the channel. And we just stuck, at a terrible angle”, Jan says.

“The wake from passing pilot boats kept splashing over the stern and into the boat. Everything was sodden”.

After that near ‘eleventh hour’ disaster, Jan and Jim were re-united with his family. They stayed just over a year, both working. Jim found work with a local shipwright, while Jan worked as a schoolteacher.

Ultimately, Jim missed the freedom of Australia and in June 1982, they departed Corpus Christi, heading back through the Caribbean towards the Panama Canal. Māori Lass was now equipped with a new and fully functioning self-steering device – a generous gift from Jim’s Great Aunt Emma Edwin.

With Jan now desperately homesick, after 6 years travelling the world, they decided to try to get back to Sydney for Christmas. Rewarding visits to the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean and Galapagos Islands, after passing through the Panama Canal, preceded a 24-day crossing of the Pacific to get home.

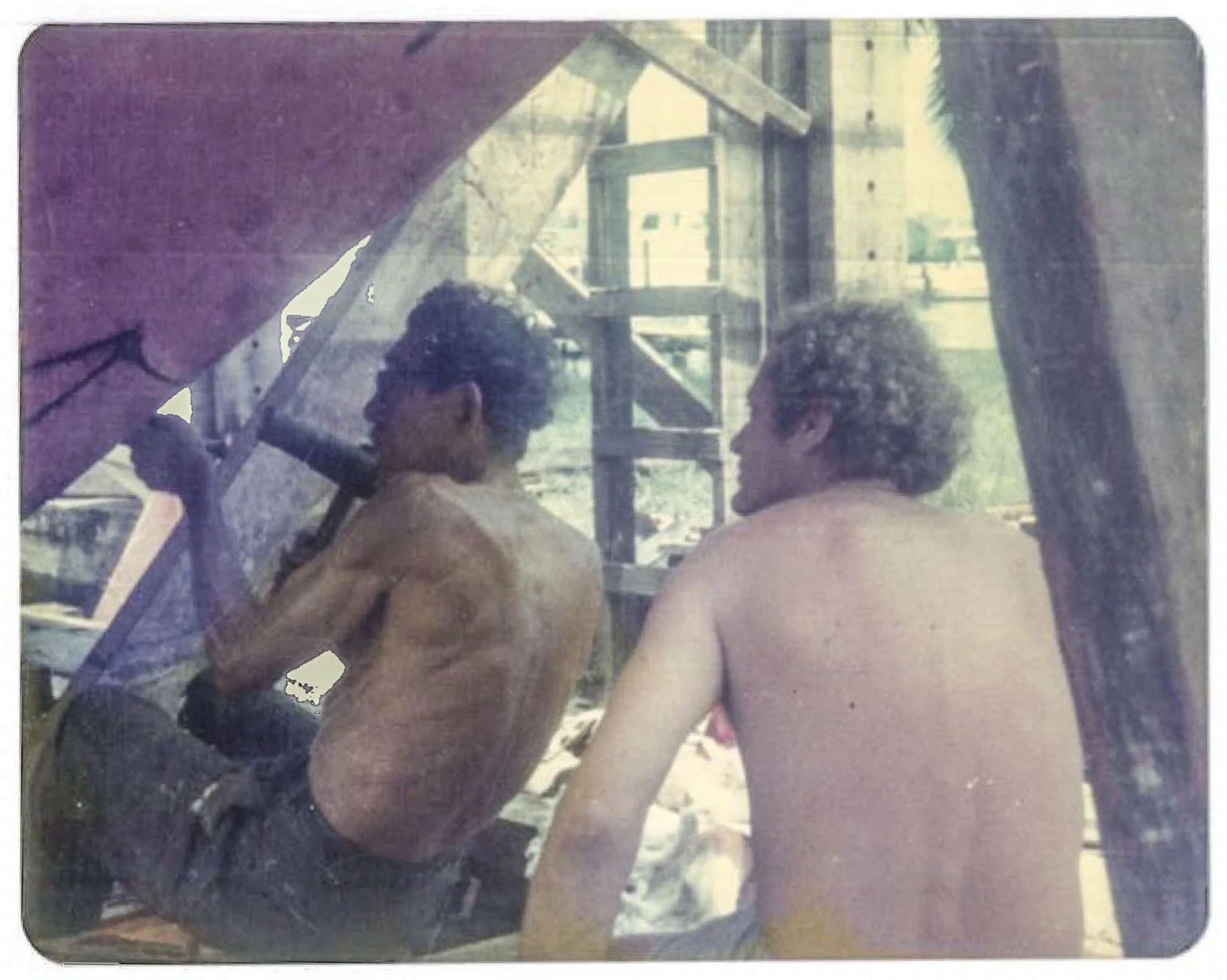

Repairing caulking in Panama. 1982

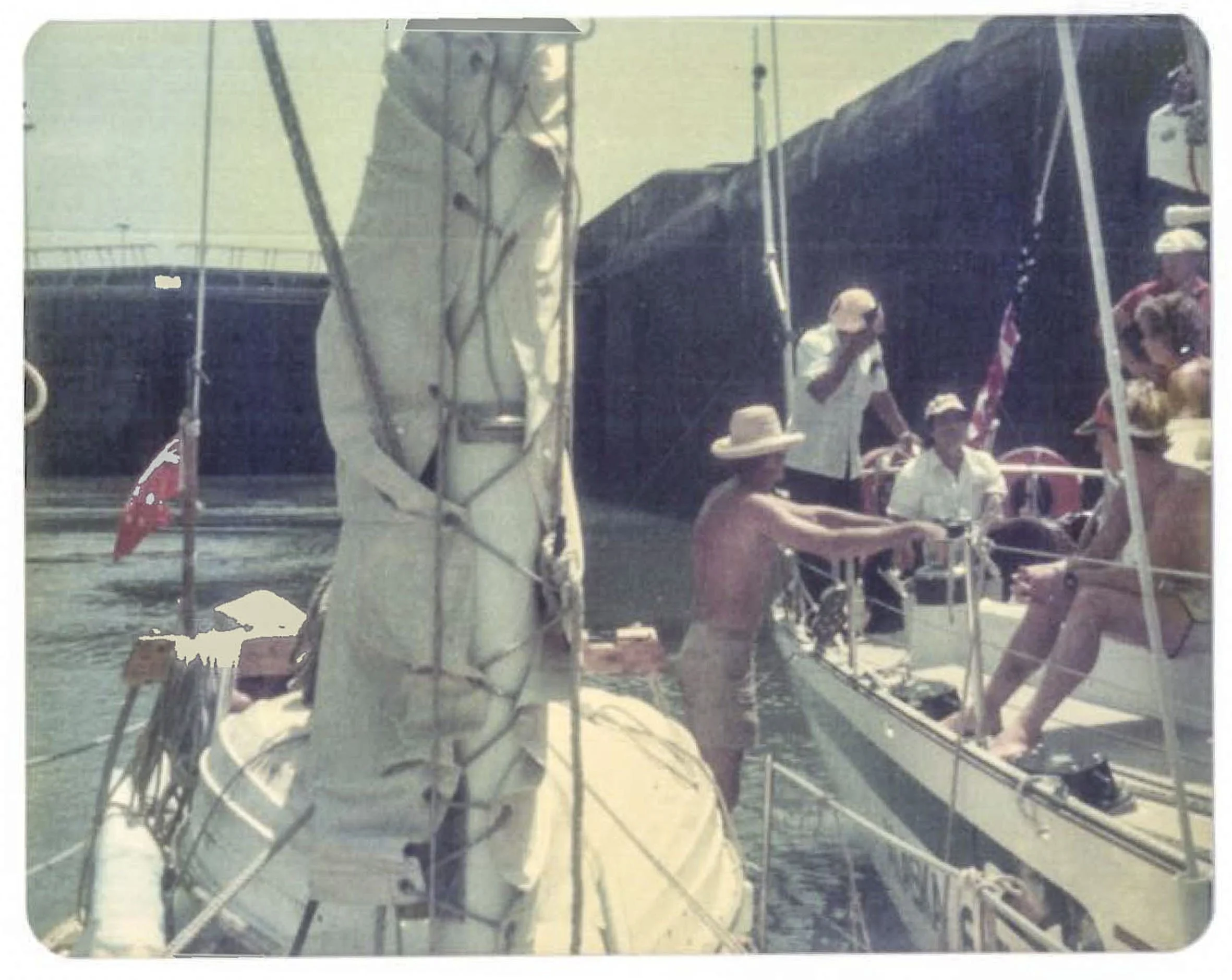

Passing through the Panama Canal. July 1982

Jan said the new self-steering system had made an enormous difference to their longer passages.

“We still take turns in sitting outside and being lookout, but meantime you can sit in the shade, read a book, or take a sea water bucket shower. We are not nearly as fatigued as we used to be”, she wrote.

Racing against the approaching cyclone season and a niggling feeling to re-enter the workforce, Jan and Jim stopped only a day or two in most places as they crossed the Pacific, apart from a stint of village life immersion on Hiva Oa in the Marquesas.

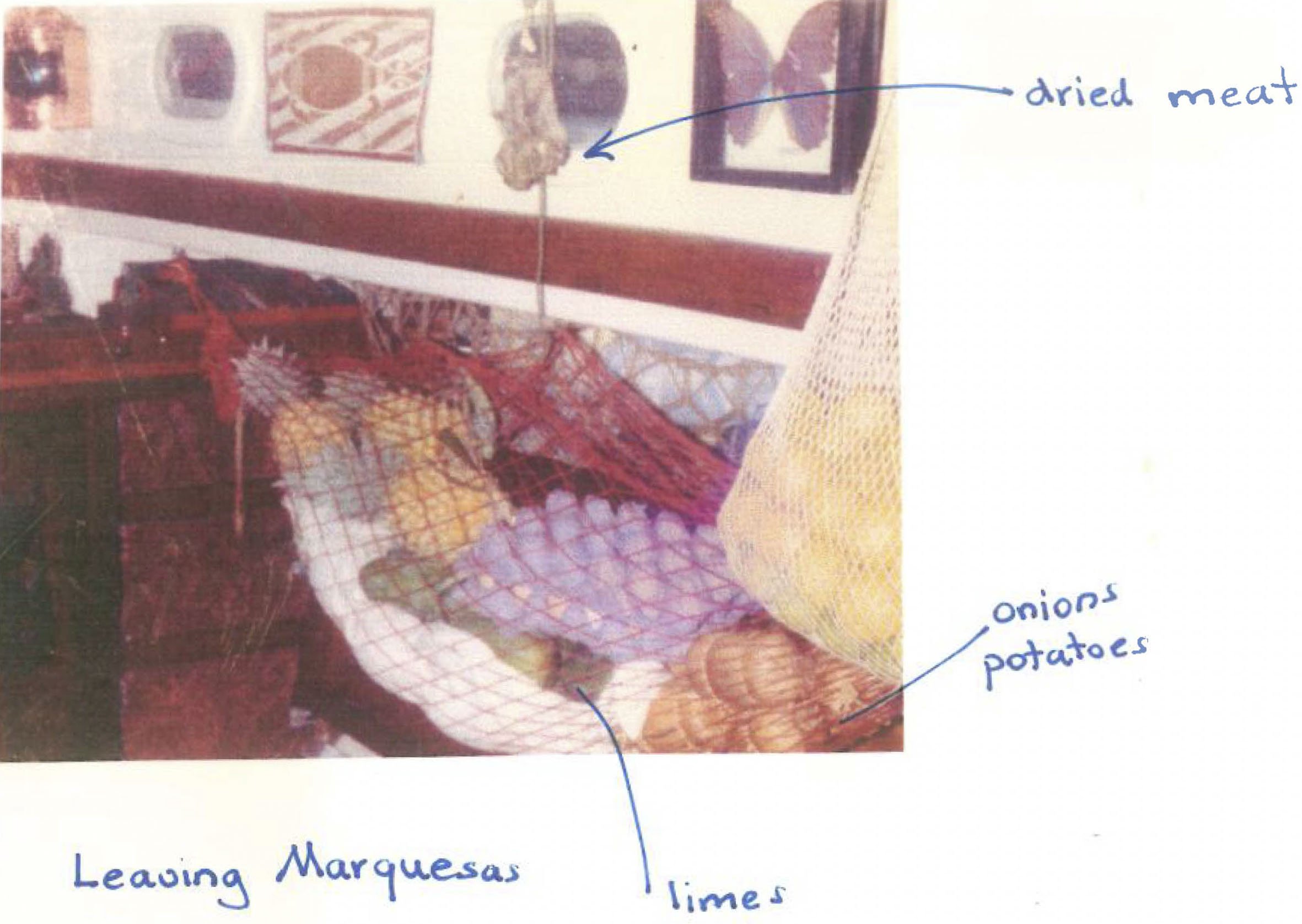

Inside MAORI LASS- Ready to leave the Marquesas Islands. 28th September 1982

“We will really be rushing the Pacific to be back in time for Christmas and avoid the cyclone season. It seems such a pity to stay only a few days in these fascinating places, but we really do need to put our backs to the grindstone for a while and join the wage-earners in NSW”, Jan wrote home to her parents.

After a full 6 years of global roaming on-board Māori Lass, Jan and Jim re-entered Sydney Harbour in November 1982, most probably to the great relief of Jan’s parents.

They’d made it back well in time for Christmas and glad to be back in Australia, but the life they’d just led still loomed large.

“We were all kind of sad to get off the boat, because that was the end”, says Jan.

“I soon missed the company of other sailors”.

Jan says there were to many serendipitous and inexplicable coincidental meetings with people connected to their lives or Māori Lass throughout their journey to detail here, but there was one final encounter that still amazes her.

“When we first sailed into Pittwater and Church Point, we stopped there and were just sitting on the boat when this man rowed past and said, ‘is that Māori Lass? Are you the couple that was in the Woman’s Weekly’, and he said, ‘my son used to own Māori Lass, I’ll come aboard and have a cup of tea’, as you do”, Jan Laughs.

He happened to be Chris Small’s dad, who lived on Scotland Island. His neighbour Robyn had a mooring available. They went to meet Robyn Smith, who to Jan’s great surprise, had been one of her schoolteachers. “It was just freaky how many things like that happened”, say Jan.

Jan and Jim moved to Queensland and took up teaching again. They kept Māori Lass on the Pittwater mooring for a couple of years before selling her.

Jan lost touch with Māori Lass for some years, until later custodians, Cheryl and Roscoe Barnett tracked Jan down and filled in the gaps.

“I hadn’t heard anything until Cheryl rang me and said, ‘are you the lady who....’”, Jan remembers.

Soon after Jan and her children travelled down to Pittwater and enjoyed a day of sailing on Māori Lass with Cheryl and Roscoe and their two children”, says Jan, remembering it as a wonderful moment.

Jan has since continued to keep an eye on Māori Lass, even travelling down to the Australian Wooden Boat Festival, the first time she was entered.

I just think it’s a wonderful boat and I’m happy to have people hear its story, but I don’t want to push myself in front of the story. It’s the boat’s story, not my story”, she says.

Reading back through her letters home Jan feels a different person to the 21-year-old who set off with her husband in 1976. “I can’t even believe it was me”, she says.

“It just feels like a different world, but when I read back through the letters, I can remember the incidents and the people”, Jan says.

As we wind up our conversation Jan tells me about her new loves of orchid growing and botanical art, but then reminds me of the connection she still feels.