Ngataki- A lesson in adventure for the 21st Century

I’ve done my fair share of adventuring through the South Pacific from the comfort of an arm chair thanks to a good book. I have devoured notable classics such as The Cruise of the Teddy by Erling Tambs, the adamantly told but ultimately discredited account of The Kon Tiki Expedition by Thor Hyerdahl and the arrogant, mildly racist and disconcerting In Quest of the Sun-The Journal of the Firecrest by Alain Gerbault.

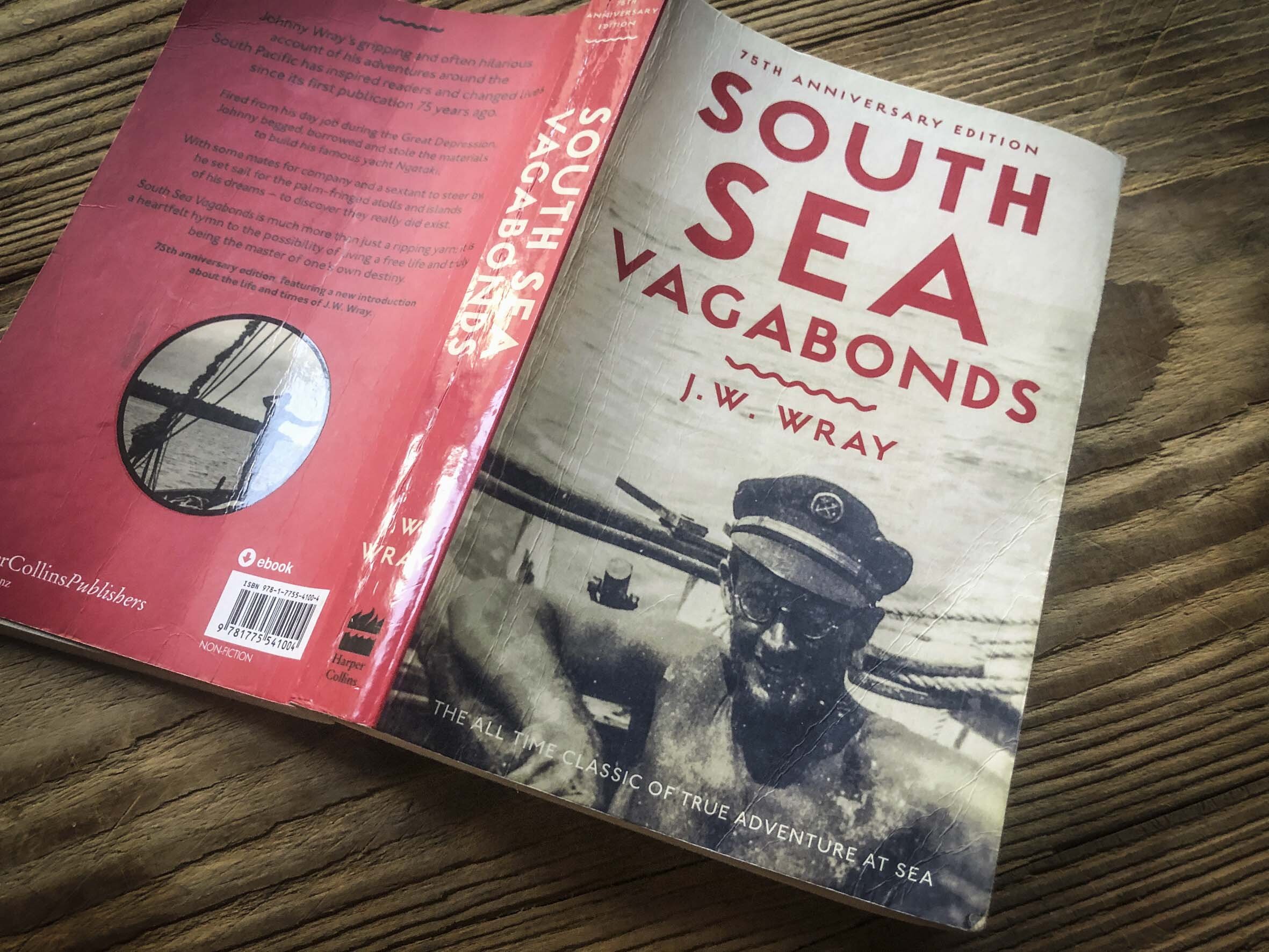

So, when I was given a copy of South Sea Vagabonds by Johnny Wray I assumed it was going to be another entertaining but outdated, perhaps pompous account of a privileged white man’s parade through the islands. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

What I found instead was an understated, self-effacing true story about the adventures of a young Aucklander that began during the great depression. The book nowadays has gathered almost cult like following from those who admire self-sufficiency and an almost naive expectation of what a motivated individual can achieve.

His form master at Auckland Grammar described his writing, as: "Conglomerations of facts occasioned by heterogeneous concatenations of stupid irrelevancies."

By the time he started South Sea Vagabonds he had become a charming story teller with an unembellished style that draws the reader into his world. This book only covers his life up until World War II and there were plenty more adventures in the late 1940’s and 50’s in his second boat. However it’s not the physical achievement of these amazing voyages that impressed me the most, but the attitude and resilience with which he followed his dreams. In this respect he should be seen as a true role model, his example made all the more important in times of over-regulation and risk adversity.

In 1932, young Johnny Wray, fired from a job he was doing indifferently, thought it a good idea to stay at home with his parents and build a boat in the front yard. He had precisely £8 10s to his name, no boat building experience, no tools and no materials.

Wray had the good fortune to be living in Auckland, in a society that was used to making do, being resourceful and not holding much store by the “proper” way to do things.

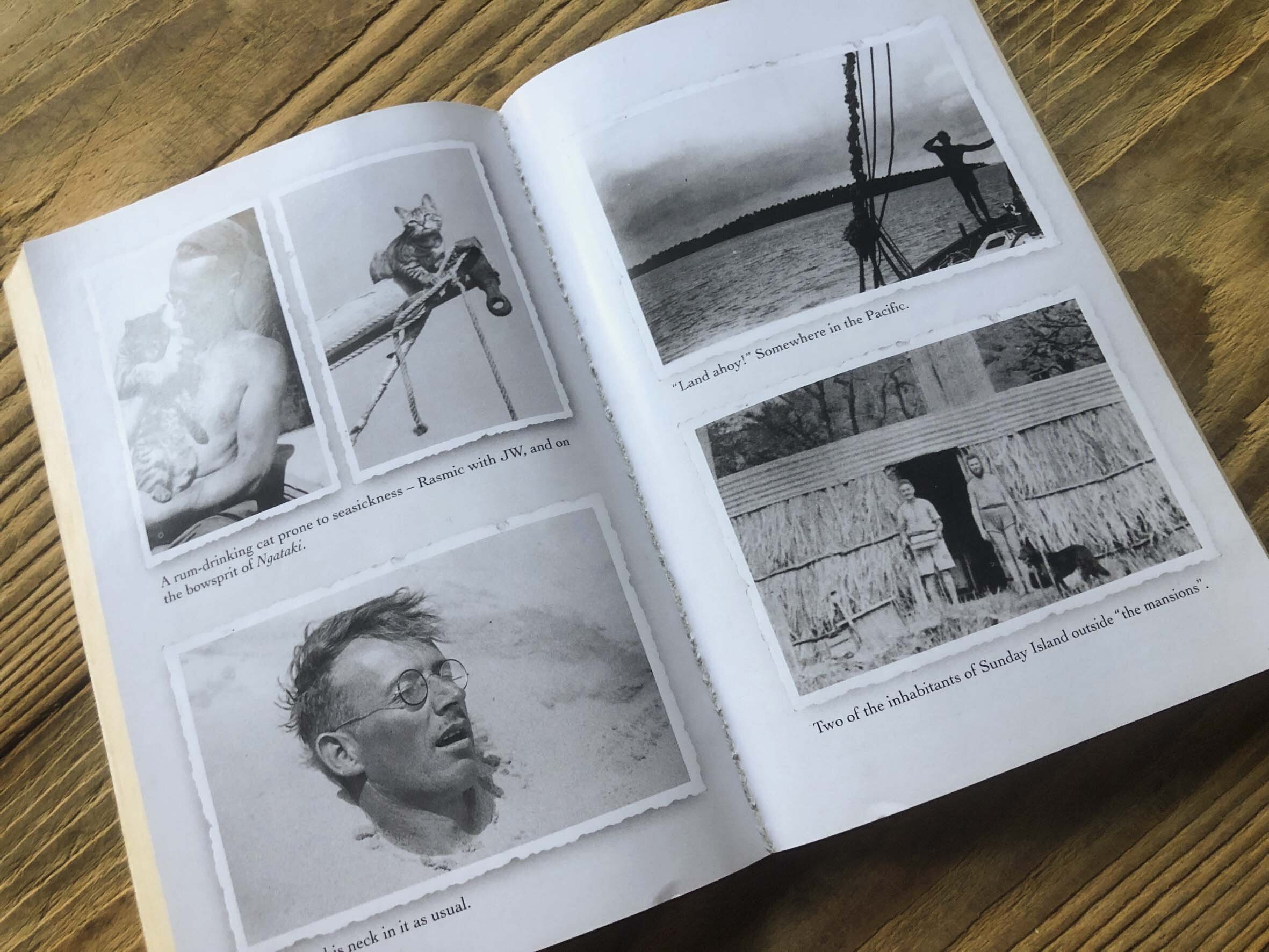

Wray collected timber from the beaches around Hauraki Gulf, using his friend’s boat to tow the massive logs home. He invented way of making do - building a solid boat at no expense all told with a charming turn of phrase.

I am not sure that I should reveal the process of the tarring and baking of the clinches, but, as I may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb, I am prepared to chance it.

One dark night you go along the road pushing a wheelbarrow containing a pick. Note: only bitumen roads more or less in the country are suitable. You look for places where the roadmen have been over-liberal and the tar is running into the grass on the side of the road. With the pick you scrape up strips of tar until you have enough and then you wheel it home. The next morning you melt up the night’s spoil in a kerosene tin. The tar melts and comes to the top and boils. You dip the clinches in it and hang them up to dry.

One afternoon, when your mother or whoever presides over the household has gone out shopping, you put the clinches in the family gas oven and roast them until they have a hard, enamel-like, black surface. It is advisable to keep a fire-extinguisher or a bucket of water handy, because there is liable to be an explosion, or at least a fire, if you are too liberal with the gas. The result, if you are lucky and have not been gassed, concussed, or burnt, is a good serviceable-looking, black-enamelled clinch.

He had a fortunate break when the salvager of the REWA a four-masted barque wrecked on Moturekareka Island, traded him some wood and materials for fresh food and relied on help from friends who lent or gave him tools and encouragement that kept him going through the long build.

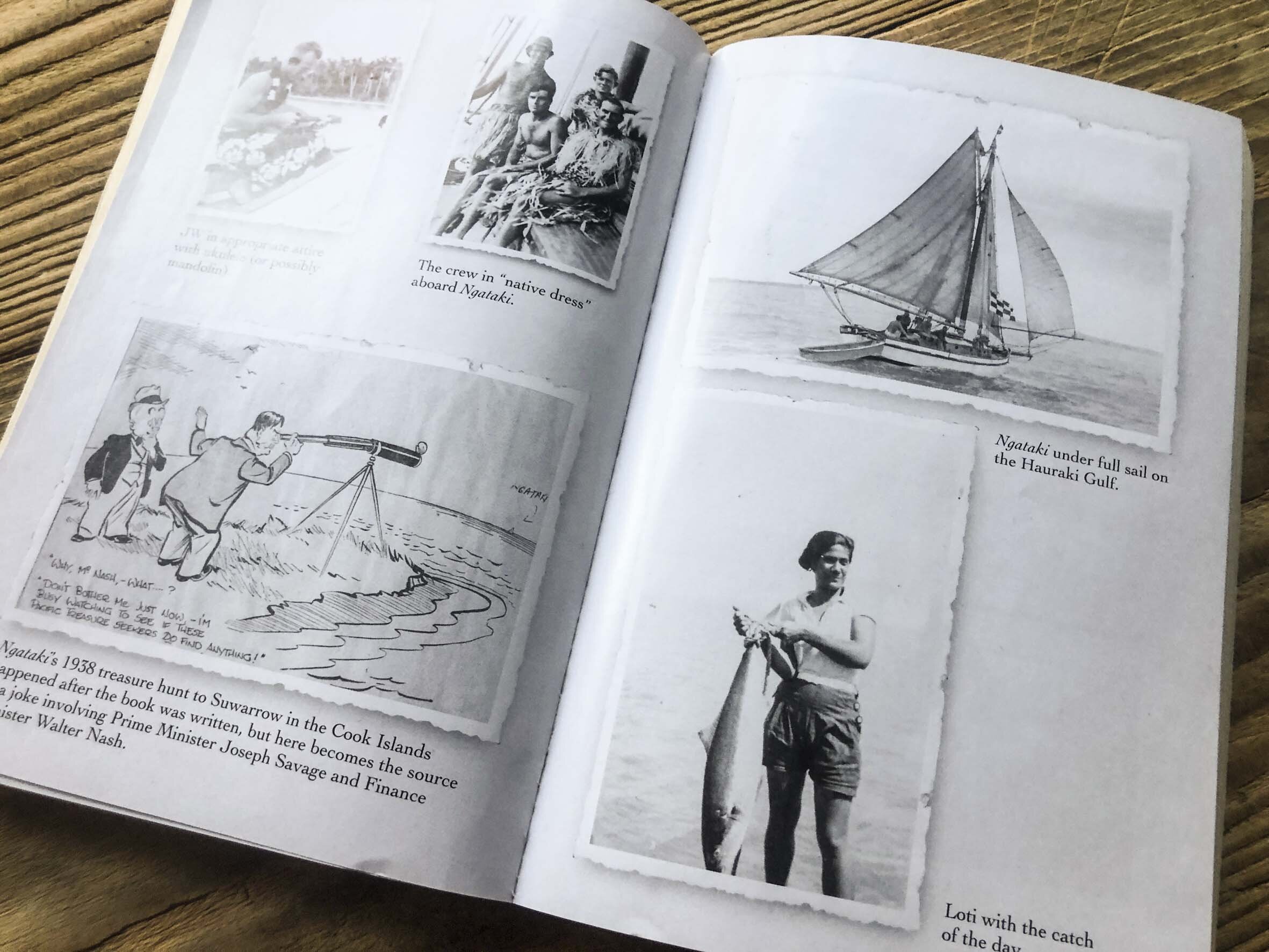

Wray settled on a name for his boat by looking through a Maori dictionary. There he found NGATAKI, which means “abode of the elite”, a strange choice as I’m sure he never saw himself as part of an elite.

In the same understated, knockabout way that he constructed his boat, Wray later pieced together this account of his travels. He not only cruised to the Kermadec Islands, Tonga and Norfolk Island but also got involved in some of the earliest ocean racing. Competing against one other boat, a ketch named TE RAPUNGA, currently being restored in Tasmania, they raced first from Auckland across the Tasman Sea to Melbourne. Then from Melbourne to Hobart. The latter event featured an unusual starting method:

My life in the Royal St. Kilda Yacht Club (now Royal Melbourne Yacht Squadron) revolved, I am afraid, mostly around the bar. I had patronized the bar fairly frequently during our stay and the bar was, I thought, a fitting place in which to start this next ocean race. So this was included in the racing rules: The crews of the competing yachts should be assembled at the bar of [the club] on the 23rd [of January]. The starting gun would be fired at 7 p.m. and the crews would consume a schooner of beer (for the benefit of the uninitiated, a “schooner” contains one imperial quart) as rapidly as possible. They would then run down the road and along the wharf and get under way.

Thus at 7 p.m. we were assembled at the bar of the Yacht Club, together with approximately half the population of Melbourne. The day had been spent largely in saying good-bye to our many Melbourne friends and as far as I was concerned, at least, the world had become a grand and wonderful place.

The starting gun was fired from the roof of the Club. Quickly we drained our schooners and said good-bye again. Not without some difficulty I headed my crew from the club. We raced across the road and along the wharf, to where NGATAKI was lying in readiness. The mooring lines were cast off, sails were hoisted and we began to move away from the wharf.

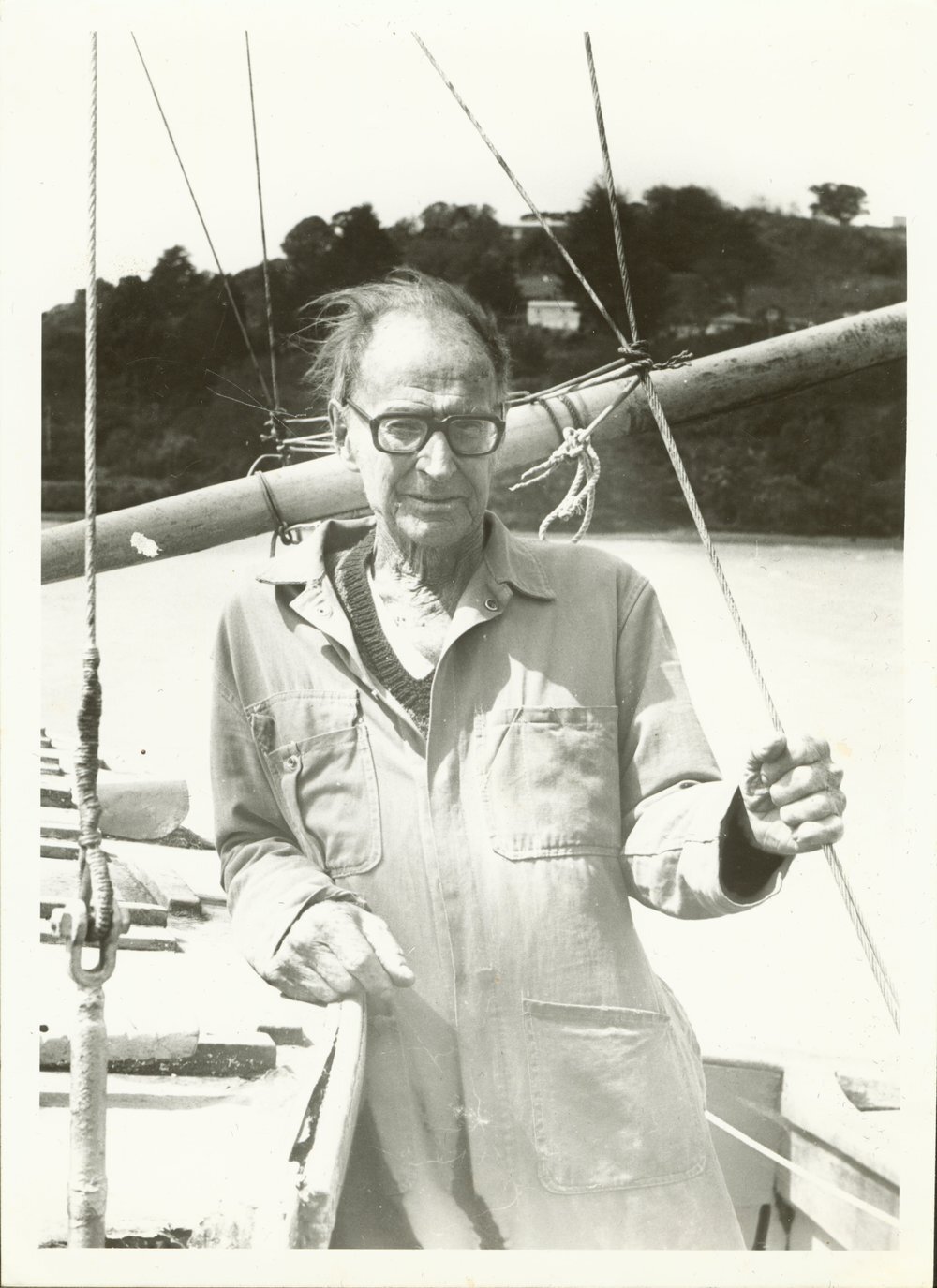

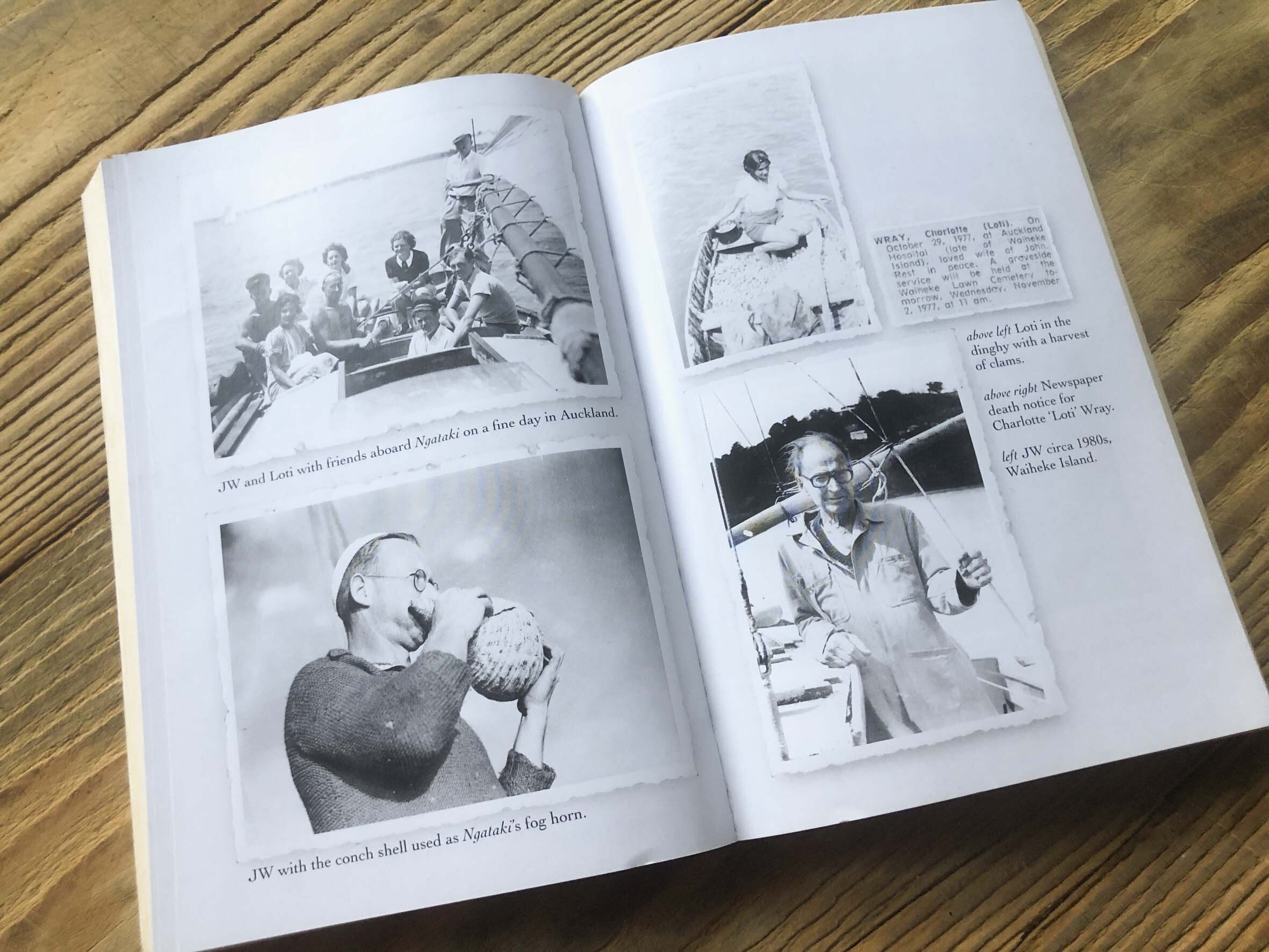

Although not part of this books story, when war came, Johnny enlisted in the RNZAF and was given the rank of Flight Sergeant. He spent the war years at Mechanics Bay and Hobsonville with the flying boat traffic that had a huge importance in the Pacific theatre. After the war he made his home on Waiheke Island with his Islander wife Loti.

Wray sold NGATAKI in 1946 and after several owners Debbie Lewis became its custodian and sailed it around the world before donating it to the Tino Rawa Trust in 2010.

In a way this treasure of a book, South Sea Vagabonds is Johnny Wray’s legacy. Or perhaps it’s the vessel that still floats in the harbour in Auckland for all to see. But I like to think that the most profound result of his extraordinary life is the changes he has made to the lives of countless men and women who he inspired to take the path less trodden.

//

EDITOR // Mark Chew