Harold Gatty-A Tasmanian Navigator

By Colin Denny

Harold Gatty 1931

THE GRANDSON OF AN IRISH HIGHWAYMAN, Harold Gatty became a pioneering navigator whose extraordinary skills and understanding of the visible universe made the world a safer place to travel.

Harold Gatty was born at Campbell Town on 6 January 1903, the third child of James and Lucy Gatty. James, the son of the convicted highwayman transported to Van Diemen's Land in 1842, was a well-respected school headmaster. James Gatty moved with his family to Zeehan on his appointment to a new school where, in 1915, St Virgil’s College awarded Harold Gatty a bursary. He left Zeehan for boarding school in Hobart.

Gatty’s St Virgil’s friend, Noel Monks, remembered the desperate loneliness of boarding so far from their families and homes. The wharf area became the boys’ playground where visiting ships stirred up dreams of adventure. Monks later wrote that the sight of the three-masted American schooner Omega sailing into Hobart made them determined to go to sea to see the world.

Gatty sat the Australian Navy’s entrance examination and joined an intake of 17 cadets at the Royal Naval College, Jervis Bay in January 1917. He struggled at the College and surprisingly, the man who was to become such a great navigator, admitted,

‘I encountered most of my difficulties mastering mathematics and navigation’.

At the end of the First World War, as the Navy demobilised, just 12 of the 17 cadets received postings. Gatty withdrew from the College without graduating and joined the merchant shipping firm James Patrick & Co of Sydney as an apprentice in 1920. Beyond the classroom, instructed by old sea dog Captain Allison aboard the SS Gabo, Gatty developed a real interest in navigation. As he stood watch at night, he wondered at the splendour of the stars of the South Seas and later recalled, ‘It is the finest possible school for instruction’.

Harold Gatty was apprenticed to SS Gabo in 1920 Photo: MMT, Slevin Collection, Gabo P_Sle_02_37

Returning to Hobart in 1924, Gatty gained his second mate’s certificate. He signed on with the Union Steamship Company oil tanker SS Orowaiti trading from California to New Zealand. Here he honed his navigation skills and experimented with new methods. The Pacific Ocean aroused his interest in the use of man’s own senses as an aid to traditional navigation.

The young deck officer became frustrated with the slow pace of advancement within the Union Steamship Company. He signed off and tried unsuccessfully to set up his own business first in Hobart and then in Sydney. Disillusioned with his failures in Australia, Gatty applied for an entry visa to work in the United States. His wife Vera and young son left for California but Harold worked on a coaster awaiting his own visa. When formalities were complete Gatty was reunited with his family on Christmas Eve 1927.

Gatty took a job as mate on the luxury schooner Goodwill, owned by US sporting-goods millionaire, Keith Spaulding.

Harold Gatty signed on as mate on the schooner Goodwill when he first arrived in the US Photo: NOAO/AURA/NSF

The following year he resigned to start a navigation school in Los Angeles. He taught mainly amateur yachtsmen and worked as a compass adjuster for both marine and aviation compasses. The latter work brought him into contact with aviators who wanted to learn to navigate. His school grew and he took on an assistant leaving him more time to research ways of improving aerial navigation. During his research, he met Lieutenant Commander Phillip VH Weems USN, a serving naval officer, who had already developed methods of teaching air navigation. The simplified procedures used tables of pre-calculated position lines called the Weems Curves.

The two navigators worked together on their research. Gatty had a mind for unravelling complex problems. An early invention was his air sextant, effectively a conventional sea sextant with a spirit level attached to create an artificial horizon, but his greatest invention was the Gatty Drift Sight.

One impediment to accurate navigation was the difficulty in determining the aircraft’s ground speed owing to the angle of drift occasioned by the wind. Gatty’s invention helped overcome the problem. It was a vast improvement on earlier instruments and formed the basis of the automatic pilot that was to become standard equipment for most aircraft.

When Weems transferred to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis to teach postgraduate navigation, Gatty took over management of the Weems navigation school in San Diego. In the textbook Weems System of Air Navigation, Weems credited Harold Gatty for the work undertaken in its compilation. He described Gatty as ‘a compass and map expert who has done more practical work on celestial navigation than any other person in the world today’. Gatty had refocussed from marine navigation as pilots throughout the world desperately sought new challenges and records. Many brilliant pilots needed good navigators and in 1929, Roscoe Turner a flamboyant former circus lion-tamer approached Gatty to navigate him in his attempt to break the US transcontinental record. In that first attempt adverse winds denied them the outright record.

Gatty’s most celebrated flight was with adventurer Wiley Post in a Lockheed Vega monoplane powered by a single Pratt and Witney Wasp engine. In 1931, Post asked the Tasmanian to join him in an attempt on the around-the-world record of 21 days held by the German airship Graf Zeppelin. Gatty accepted the offer and they took off in the Winnie Mae from New York’s Roosevelt Field on June 23, 1931. Winnie Mae landed back at Roosevelt Field after circumnavigating the globe in a flight lasting less than nine days. They received a hero’s welcome and were each awarded the US Distinguished Flying Cross, the first civilians so honoured.

U156797ACME – the original caption on 23 June 1931 read “Roosevelt Field, N.Y., Harold Gatty and Wiley Post, the two adventurous aviators who intend to circle the globe in ten days, took off on the first hop of their journey from Roosevelt Field, N.Y., to Harbour Grace, Newfoundland in the mist.” Photo: © Bettmann/CORBIS.

In January 1932, Gatty accepted the position of Chief Air Service Navigation Research Engineer with the United States Army Air Corps. He made it clear that he would not forgo his Australian citizenship so Congress passed a special act to allow him to take up the position. Gatty then set up the military celestial navigation schools that taught the officers who were to control US strategic air operations.

Maritime and terrestrial navigation requires two-dimensional coordinates. Once in the air a third coordinate comes into play — altitude. It was Gatty’s research and practical application that led to a solution to many of the complex problems associated with three-dimensional navigation.

Following the outbreak of the war in the Pacific in 1941 Gatty returned to Australia as Director of Air Transport for the South West Pacific with the rank of Group Captain in the RAAF. His work resulted in a remarkable improvement in the movement of supplies but in early 1943, following the defeat of Japanese forces in New Guinea, Gatty stepped down from the position and returned to the US.

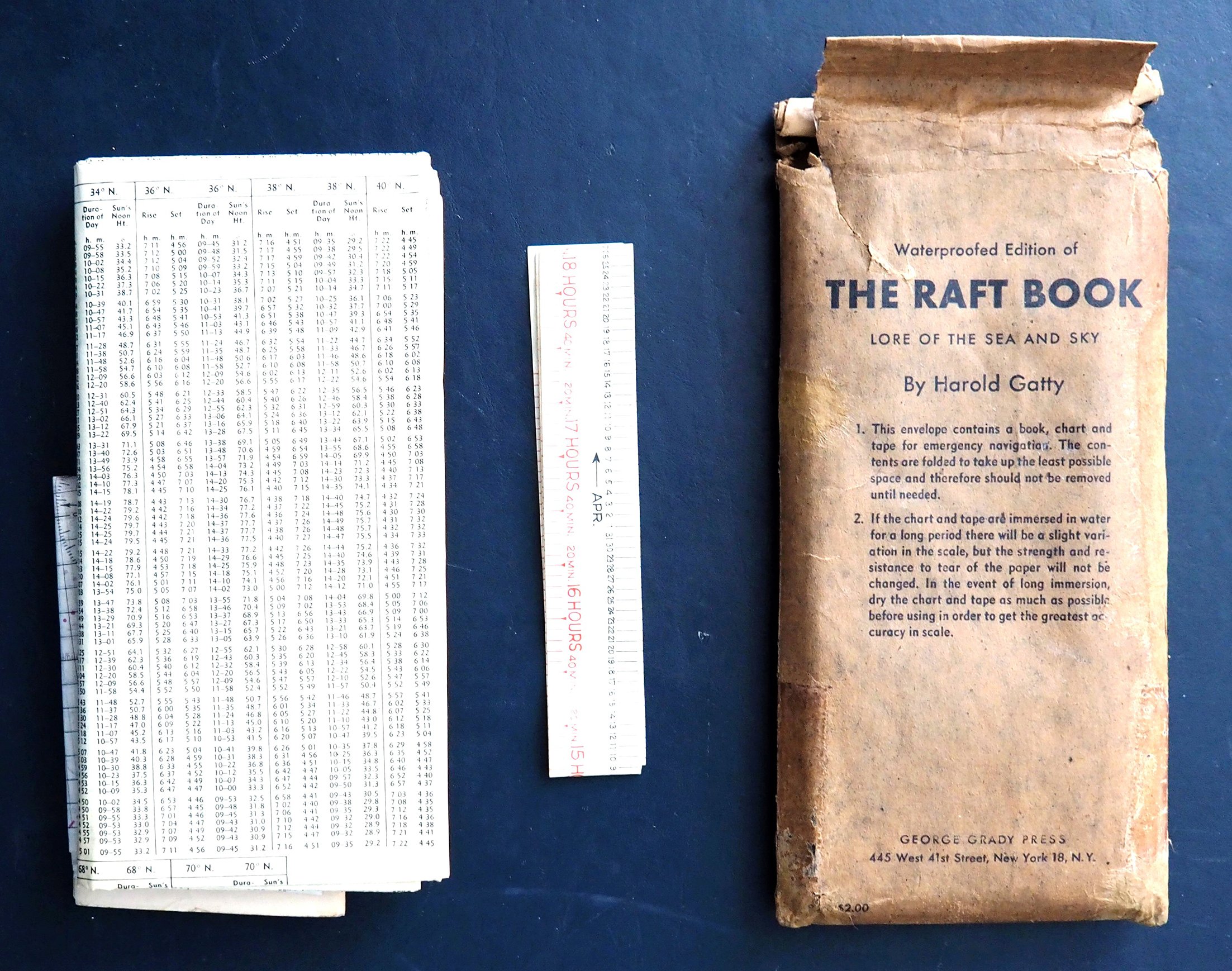

He set about writing a book for the US Navy to help downed navy airmen survive and navigate their life rafts. The emergency maritime navigation manual was called The Raft Book and was placed in the survival kits of every allied airman in the Pacific. (Click to enlarge)

After the Second World War, Gatty moved to Fiji to work. Here he wrote Nature is Your Guide, a book on navigation using natural senses and powers of observation. It was published after his sudden death by stroke in 1957 when just 54 years old.

On a visit to Annapolis in April 1968, this writer met the famous navigator PVH Weems who had been in business with Harold Gatty. Weems confirmed that Harold Gatty had developed many of the principles of three-dimensional celestial navigation for aircraft and said Gatty’s earlier research work was critical to the understanding of navigation in space.

Gatty is indeed a celebrated Tasmanian navigator.

Colin Denny’s interests include sailing and maritime history. He works as a volunteer at the Maritime Museum of Tasmania and his maritime history articles have been widely published.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2023 edition of the Maritime Times. Many thanks to The Maritime Museum of Tasmania for allowing us to re-publish.