ME, THE BOAT AND A GUY NAMED BOB: Cruising the West Indies With Dylan

This book was first brought to my attention by Mike Strong, custodian of the 1935 S&S LANDFALL. This review is reproduced by kind permission of its author, Charles Doane who runs the wonderfully rich, eclectic and informative site Wavetrain We strongly encourage you to visit.

Bob Dylan is of course a famously opaque character, and one of the more opaque episodes of his life concerns a certain boat he once owned. It is almost mythical, the stuff of legend among sailors in the Caribbean today. But it is in fact true: the last large traditional schooner built on the island of Bequia, WATER PEARL, launched in December 1979, was built for Bob Dylan. But not just for Bob. He had a partner, Chris Bowman, originally from California, who has now shared the full story of Dylan’s career as a West Indies schoonerman in his wonderful memoir Me, the Boat and a Guy Named Bob.

Bowman more or less accidentally fell into the life of a seafaring vagabond when he was young, starting first in the Seychelles in the western Indian Ocean. After crewing across the Atlantic with a mad Mexican named Francisco in a tiny unfit boat that lost its rudder halfway over, Bowman arrived in the Caribbean and soon enough was in a boat of his own, a small, nearly derelict local sloop, CORSAIR, that he found on a beach in Prickly Bay, Grenada. He and a friend sailed CORSAIR up to Bequia in 1975 and barely made it. They ended up sailing the boat hard on to the beach there to save it from sinking.

It was a propitious stranding, as Bowman had landed right in the middle of Bequia’s boatbuilding scene. He soon was tight with master builder Loren Dewar, sailmaker Lincoln “Bluesy” Simmons, and the whole tribe of locals who were then keeping the traditional craft alive. With their help Bowman soon repaired CORSAIR, but then went on to build himself a new boat from scratch, a 40-foot gaff sloop he named JUST NOW.

JUST NOW under sail, looking much like a cutter. In the old island parlance any craft small enough to haul up on a beach when not in use is a boat; anything bigger is a vessel. A sloop is any vessel with just one mast

To my mind the most interesting part of this book is Bowman’s granular description of the process of building JUST NOW. The forays into “the bush” to find appropriate shaped trees, felling them by hand, and man-hauling out the raw lumber. Framing up a hull on a beach, with nothing but eyeballs and hand tools to make it fair. Traveling to Guyana to buy and mill silver bali lumber for the planking. The wheeling and dealing necessary to lay hands on hardware and get it shipped to Bequia. It’s all fascinating stuff. Well worth the price of admission alone.

I was also amazed and pleased to find several familiar names in this text. Steve Hollis, known to many as the master of Ocean Sails in Bermuda, who was then cruising the islands on his Venus ketch ZEPHYRUS. Klaus Alvermann, who circumnavigated the world aboard the tiny, but famous boat PLUMBELLY he built in Bequia with Loren Dewar in the 1960s. The enigmatic and super-resourceful Henry Wakelam, Bernard Moitessier’s best buddy and partner-in-crime from the earliest phases of his career. Reid Stowe, the semi-mystic longest voyage record-holder of whom I have often written in my blog. Chris Doyle, who went on to publish his now-ubiquitous Doyle’s Guides to the Caribbean. Sally Erdle, founder of Caribbean Compass, the popular local sailing magazine (which I understand she is now trying to sell, in case you’re interested). To name only a few.

But don’t get me wrong. The parts about Bob Dylan are very interesting too. He and Bowman fell into their partnership quite haphazardly. Soon after he finished building JUST NOW, Bowman happened to be visiting family in California and reconnected with an old buddy there who happened to be working for a high-powered contractor who was then building a house for Dylan in Malibu. Bowman showed his friend photos of the boat he’d just launched in Bequia, his friend showed these to his boss, and the boss was soon obsessed with the idea of owning a big traditional boat built in Bequia. He convinced Dylan to go in with him on it, and together they commissioned Bowman to build them a 63-foot schooner on the beach in Bequia in just a year.

Over a year later, not surprisingly, the boat wasn’t finished. The contractor got snappy and wanted to bail, and Bowman saved the situation with a compromise: he gave the contractor JUST NOW in exchange for his half-share of the unfinished schooner.

“Well, I guess we are partners now,” Bowman said to Dylan after the swap was agreed to.

“Yeah… I guess we are,” answered Dylan. “Hang on a minute and I’ll get you my numbers.”

The schooner WATER PEARL in the earliest stages of construction

Chris Bowman and a co-worker scoping out lumber for the boat

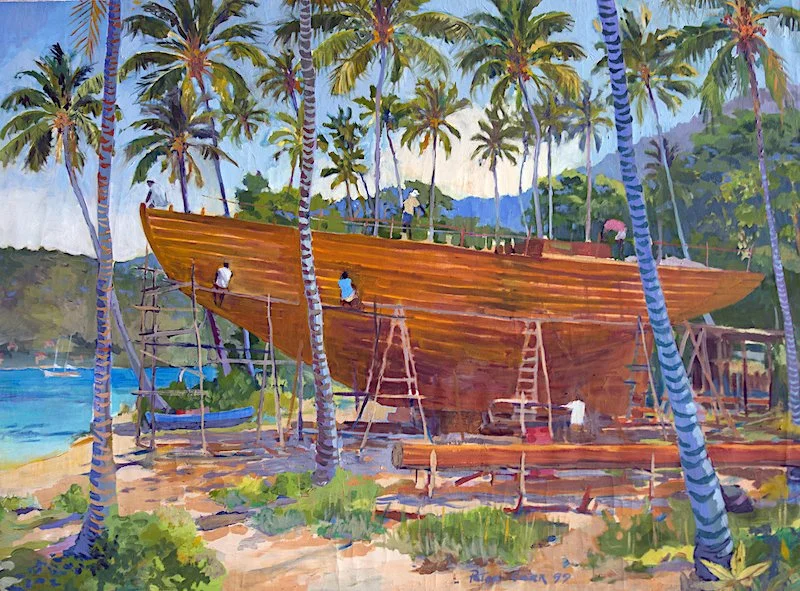

Painting by Australian artist Peter Carr of WATER PEARL after her planking went on

Launch day! Much of the island turned out to help haul the big schooner off the beach

Launch day, another view. Dylan, alas, was not in attendance

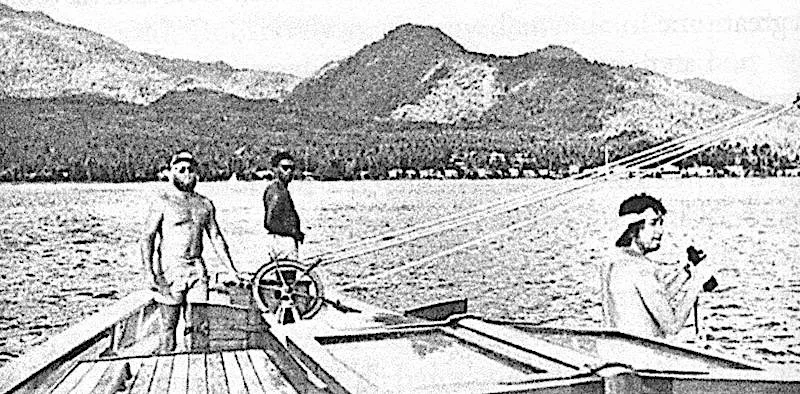

WATER PEARL post-launch, underway

With Bob onboard. That’s him on the right with the binoculars. Bowman’s at the wheel. The island in the background is Dominica

Over the several years Bowman owned the boat with Dylan it’s fair to say he got to know the man better than most. He shares much of this knowledge with his readers, but still he makes it clear that Dylan, at his core, is unknowable. Bowman understood very quickly that the famous troubadour was shy and diffident around strangers and avoided social situations that put him at the center of attention. One of my favorite scenes in the book, after Dylan first starts visiting the schooner, is when Bowman is taking him ashore to a party on Bequia and realizes if they come in together, Dylan will likely be mobbed by curious locals. So he stops in the anchorage at PLUMBELLY, and leaves Dylan to visit with Klaus Alvermann, while he continues on alone. I, for one, wouldn’t have minded being a fly on the wall aboard PLUMBELLY that night! Later Klaus and Dylan snuck ashore separately and Bob got to join the party without anyone really noticing.

One of the interesting things about Bowman’s relationship with Dylan is that it seems Bowman in fact spent more time in Dylan’s world than Dylan spent in his. Early on the singer invited his schooner buddy, and later Bowman’s wife and young daughter as well, to join him on tour. In all Bowman traveled with the star on three different tours and got a fine bird’s eye view of life on the road with famous rock stars.

The sad end of the story is that Bowman ultimately lost WATER PEARL on a reef near the Panama Canal entrance in 1988. There’s been a lot of speculation over the years as to how exactly this happened, and Bowman here finally tells the tale in full. He makes it clear his willingness to share it publicly has been a long time coming. In a review that perhaps already has too many spoilers in it, I’ll save you this one to marvel over when you read the book for yourselves.

WATER PEARL soon after the wreck in Panama. Despite dogged efforts on Bowman’s part, she never got off the reef

Dylan’s reaction when he first heard what happened was, perhaps not surprisingly, pretty sanguine.

“Man,” he told Bowman, “it’s like that reef has been sitting there waiting for you since the very beginning.”

First thing I did after reading this book was watch this great 2015 documentary, Vanishing Sail, about traditional boatbuilding in the West Indies. I recommend you drop a few dollars and do the same! It’s a beautiful film.

The story of Water Pearl is briefly mentioned at 45:11 to 48 minutes in. If you do watch you’ll notice that Nolly Simmons (son of Bluesy Simmons) disparagingly describes Bowman as having been an apprentice on the project. This is unfair, to say the least. Nolly and Bowman were in fact equal partners on their side of the original deal to build the boat, then had a falling out after Bowman became a co-owner with Dylan. Nolly, it seems, still hasn’t gotten over it.

And on a personal note: I spent some time with Bob Dylan once during the time he owned Water Pearl. About 1984 or ‘85, I’d guess. But this wasn’t in the West Indies. It was in a traffic jam on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, a few blocks north of Grand Army Plaza. We were stuck in two separate vehicles, side by side, for many long minutes. Bob was in the backseat of his car, which otherwise was filled with orthodox Sephardic Jews. Me and my friend Tom Gilbert, immobilized alongside in my old Ford Courier truck, tried hard not to gape at them too much.