PHINISI

By Charlie Salter

Borobudur temple Bas-relief Java 8C. Photo van Kinsbergen 1874 Tropen Museum

INDONESIAN WOODEN BOATS

Traditional wooden boatbuilding and seafaring are integral to the long history of an archipelago of islands that became Indonesia. For more than a thousand years boats have underpinned trade, fishing and communication between these islands. Indonesia as a nation state is a post war construct, but historically linked by its geography and culture. As recent as the 20C Indonesians were governed by Dutch and Japanese overlords, while always maintaining their loyalties to island regencies with their different traditions, religions and languages.

This is Australia’s northern neighbour that we sadly ignore except when making a holiday dash to Denpasar. From an aeroplane you can often see tiny outriggers fishing and navigating by experience far out to sea, when you still have hours to go before landing. Early in the morning, from your breakfast deck, you might see the local village fishing fleet returning to the beach with a depleted catch being carried away in baskets to the roadside or market. By lunch you might have taken a ride in a local Junkung before flying to Flores to board your luxurious Phinisi dive cruise.

Jungkung C1970. Photo Tropen Museum Amsterdam

Tourism has coloured our simple understanding of Indonesia. Yet Indonesians have a rich and sophisticated cultural history mixed with Chinese and European influences from sea trading. The Dutch East Indies Company or Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC) privately colonised and exploited the islands for hundreds of years. This would be like Australia being colonised by Google today with the blessing of the US government. The tiny volcanic islands of Banda, initially the only producer of nutmeg, were fought over by the Dutch and English, devastating the local inhabitants. Years of valuable spice trading brought European maritime design to the archipelago, especially to shipping ports in Makassar South Sulawesi (Ujungpandang, Celebes) and Ambon in the Moluccas.

At the same time, large fleets of Makassan Praus would arrive with the annual North-west December monsoon along the Arnhem and Kimberly coasts of Australia. They came to harvest trepang (sea-cucumber), a luxury product in China. The Makassans set up camps to process, dry and smoke the trepang before returning on the South-east trades during the winter. Local indigenous tribes worked with the visitors stockpiling pearls, turtle shell and sandalwood to trade in the following season.

In the last 15 years Australian archaeologists have been documenting the interaction between Australian aborigines and the Makassans. New work is being done on the rock art of the Kimberley and Groote Eylandt that depict European and Makassan designed ships, including two masted trading schooners.

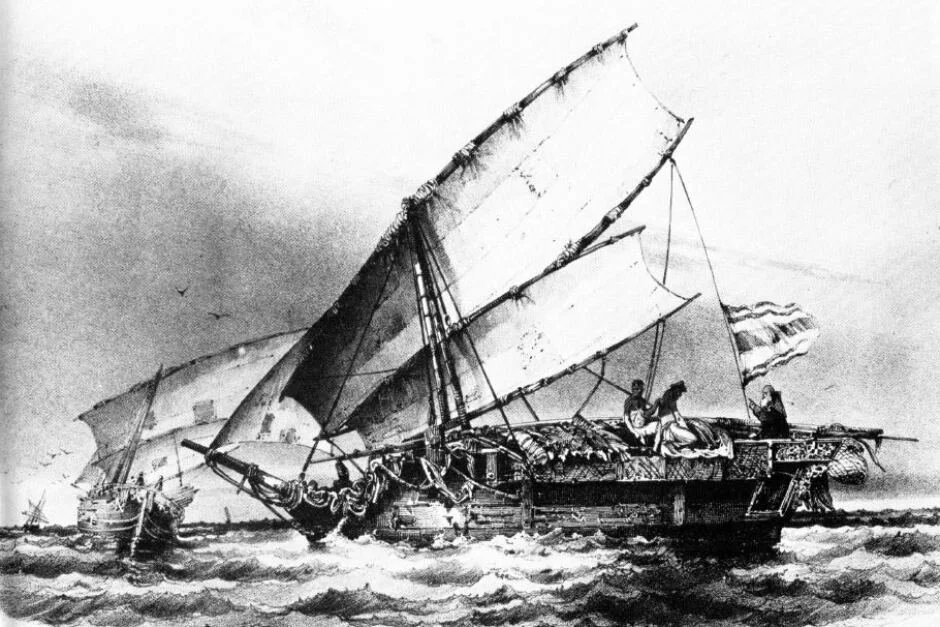

Makassan Praus. Etching from 1836

INTANGIBLE HERITAGE

In 2017, this rich Indonesian maritime history was included in UNESCO’s Intangible World Cultural Heritage List. The citation recognised the cultural significance of the “Art of Boatbuilding in South Sulawesi” that is best known for the Pelari and more recently Phinisi boats. Horst Liebner, a German scholar of Indonesian maritime history describes;

“The underlying tradition of shipbuilding and navigation was a knowledge system operating for 5000 years by the peoples of S E Asia and Pacific Ocean. They developed the hardware and software necessary for intentional sea travel, the very techniques that allowed them to colonise and be colonised ....... Ships are the most complex artefact routinely produced prior to the Industrial Revolution ... fit to go from one country to another allowing intermingling of cultures and interchange and adoption of foreign ideas and methods”.

Indonesia, unlike many Asian countries has preserved its craft traditions, often discarded and lost as 20C governments were keen to modernise. An example is my years of experience with Javanese carpenters. They would build large roof trusses, using only hand tools and instinctive estimates of structure. I only provided the span, ridge height and if the roof was finished in tiles or lightweight corrugated sheet. Large timber flitches were beautifully scarfed and jointed on the ground and chain winched to the wall. Mechanical bolts and stitching plates are not necessary.

Scarfs are done, now for the dovetails. Sanur beach Bali 2020. Photo by the Author

PALARI or PHINISI

The wooden Palari, now commonly called Phinisi, is still built by hand and eye on the tidal flats and beaches of South Sulawesi. This boat has become an imaginary symbol of maritime Indonesia. It still serves as a basic cargo ship while being casually used in advertising promotions. The nostalgia is played up to tourists, with advertising for cruising, dining and diving on a 5 star spice trader. Liebner acknowledges the romance, even in the UNESCO citation, but has done serious work tracking development and influences on wooden boat design in the archipelago. His work shows the Phinisi is not one type from one time, but like most things maritime, ever evolving and adapting both western and eastern influences. Liebner’s work demonstrates that the Phinisi hull and rig are quite unique to this South Sulawesi boat.

Phinisi with timber cargo, Kalimantan 1983. Photo Jeffrey Mellefont ANMM

Palari at Makassar 1932. Photo Geoffrey Ingleton ANMM

PHINISI RIGS

Malay sailors were the first to use a lug sail. Variations of this rig are still used today. These are square sails set fore and aft and tilted down at the end. They can be pivoted sideways, which makes it possible to sail downwind or into an oncoming wind at a tacking angle. From a distance the tilted shape makes it look triangular and similar to a lateen sail, with a single top yard which was developed by the Polynesians to the east and Arabs to the west.

The Makassan paduakan rigs were a manoeuvrable variation of the traditional oblong tanja sails with an upper and lower spar used and documented from the 8C. By the early 18C, Indonesian rigs started to follow European trading Toops of the Dutch East Indies Company. From the early 19C European gaff schooner rigs started to appear on military and commercial ships in the Indonesian archipelago. These could easily out-sail the local Junkung or tanja rigged Praus especially in monsoon season.

The Phinisi are often incorrectly compared to gaff schooners, as both set seven to eight sails on fore-and-aft masts along the centreline of the hull. However, Liebner notes, the sail arrangements on a Phinisi are unquestionably non-Western. The mainsails are lashed to the masts then pulled out like curtains along lateral spars already fixed to the masts, and not, as on a typical schooner, raised with the gaff. While this seems a small detail, the sail handling is very different and adapts the rigging and functions of the earlier tanja rigs.

Grayhound with Lug rig

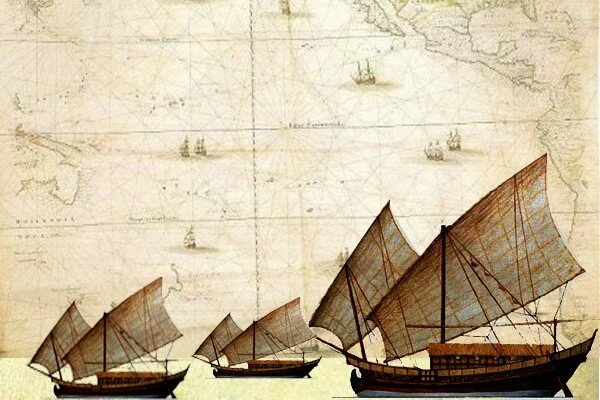

Paduakan rigs in the Celebes 1863

Palari with “curtain” sails. Celebes 1923. Tropen Museum Amsterdam

PHINISI CONSTRUCTION

Most boatbuilding in South Sulawesi today is done along the beach at Tana Beru. Here hundreds of vessels are at different stages of construction. The Phinisi hull form, length and beam come in a huge range of dimensions. These are not documented with drawings or controlled with templates but come naturally out of the master shipwright’s knowledge. An 18C observer noted;

“Shipwrights build their praus, which they call Paduakans, very tight, by first doweling the planks together, and later fit framing timbers to the planks. In Europe we build reversely; we set up the framing timbers first, and fit the planks to them afterwards.”

The Sulawesi construction method and order are opposite to western methods. Western tradition forms the hull shape by establishing a sequence of curved frames or templates at stations along a laid keel. The frames or ribs are then sheathed with pre-sawn planks.

The Sulawesi Phinisi builds the shell first by assembling planking before fitting the internal ribbing and framework. The shape and lines of a hull must be read from the run of the planking alone. The planks are carved to shape with the changing geometry using sequences of shorter planks. The plank patterns, stipulating exact placement, length, shape and joint are well known to the master shipwright. As the planks are fitted, they are doweled together. To achieve symmetry, it is normal to cut pairs of mirrored larboard and starboard planks from a single timber log, here described by a 19C traveller;

“To make each pair of planks used in the construction of the larger boats an entire tree is consumed. It is cut across to the proper length, and then hewn longitudinally into two equal portions. Each of these forms a plank by cutting down with the axe to a uniform thickness. Along the centre of each plank a series of projecting pieces are left, standing up three or four inches, about the same width, and a foot long. These are of great importance in the construction of the vessel”. These raised thicknesses or tambuku along the plank allowed the later fitting and lashing of the internal frames and ribs.

Here then is the intangible uniqueness of South Sulawesi shipbuilding.

Laying plank patterns and dowels. Photo Prof. Sarah Ward Tana Beru 2018

Followed by the frames. Photo Prof. Sarah Ward Tana Beru 2018

Square stern, central rudder and prop. Photo Prof. Sarah Ward Tana Beru 2018

MODERN PHINISI

After hundreds of years and mostly since the 1970’s further adaptions have been made. The original double ended boat with two aft quarter oar rudders have been replaced by a central rudder and square stern. The broad stern is needed to house the motor to make an efficient trading ship. This fundamentally changes the loads and stresses and requires adaption of the faming from traditional designs that relied mostly on the integrity of the planking or shell.

The boatbuilders are in South Sulawesi for good reason. They have direct access to the best timber resources. Kayu Ulin (ironwood) is perfect for planking below the waterline while Sappanwood is the preferred material for dowels. These precious resources are almost exhausted in Sulawesi and better controlled by logging management. Many traditional shipbuilders are moving west to Kalimantan (Borneo) where there are still resources of Ulin and Bankirai timbers suitable for the work.

Like many traditions, the magnetic metropolis is luring young people away from Sulawesi. Very few labourers working today in the shipbuilding villages will have actually seen a traditional Pelari or Phinisi. Further, the masters or Panrita Lopi are old and few. Reaching this knowledge status is a long hard apprenticeship that few people wish to follow.

Phinisi boats are still used to ship goods but also fitted for tourism. These are expensive cruise ships mostly based in Labuan Bajo Flores. Often the hull is built in Sulawesi then towed to Flores where it is lavishly fitted out. The sails and quarter oars are added as decoration, while the powerful motors can get you to the dive sites in Banda or Raja Ampat in West Papua in a few days. If you have a fistful of US$, SWS can recommend Alila Hotels Phinisi Purnama.

Unloading a Phinisi in Manado, Sulawesi 2015. Photo Beat Presser SEA Globe

Alila Purnama KLM FULL MOON. Labuan Bajo Flores 2018. Photo by the Author

55m Phinisi charter KLM PRANA in Labuan Bajo. USD 87,500pw. Photo Atzaro

CREDITS

SWS acknowledge the detailed research work of Horst Liebner and Jeffrey Mellefont of the Australian National Maritime Museum.