Ropes, Boots and Adventure.

In the second-hand bookshops I sometimes frequent, I’ve noticed that the “Maritime” section is often very close to the “Mountaineering” books. It’s not an alphabetical thing. I think it’s just that the bookshop owners believe that the two disciplines have a lot in common, (too much fresh air, an element of danger, isolation, fear etc) and so a potential shopper who is interested in one, might well be interested in the other.

The view over Bathurst Harbour from the top of Mount Rugby

A few years ago, we took FAIR WINDS down the West Coast of Tasmania and spent a few days in one of the most magnificent harbours in the world, Port Davey. There is a small, almost fully enclosed anchorage called Iola Bay, on the south side of the Bathurst Narrows and from here it’s an easy dingy ride across to a little beach in Starvation Cove (more information on this naming story please!) which is the start of the 770m climb to the top of Mount Rugby.

Apparently Parks Tasmania are no longer maintaining the track, but even when they were, it was more of a bush bash than a case of following the path. The views from halfway up were spectacular. I’ve no idea what the views from the top were like because as should be expected in this part of the world, the clouds closed in just as we approached the summit. It was just a tough day’s walking and an unremarkable achievement, but I’ve often wondered why the activities of trekking/climbing and small boat sailing are not more frequently combined. There are overlaps in attitude, aptitude, equipment and geography that to me make a two-part land and sea adventure very appealing.

There are a few shining examples of where the two disciplines have intersected either by necessity or by choice.

The Three Peaks Race

The UK’s Barmouth to Fort William Three Peaks Yacht Race is a unique event combining sailing, running and a little cycling that has become one of the toughest long-distance events in the world.

The adventures of H.W. (Bill) Tilman, the climber and sailor who lived in Barmouth, was the inspiration behind the idea, which was conceived by his doctor, Rob Haworth. Rob spent many hours talking to Tilman about his adventures, and as a result came up with the idea of spending his holidays doing a “mini Tilman”, sailing from Barmouth to Fort William and en route reaching the top of each of the highest peaks in Wales, England, and Scotland by foot.

The idea of making it into a race came from Rob Haworth’s partner, Dr Merfyn Jones. Sitting around the kitchen table on a winter’s evening in 1976 Rob recounted his idea for his holidays. Merfyn heard him out and then said, “wouldn’t it make a marvellous race”.

They set out a rough map using kitchen utensils, with bottles to represent the mountains, and worked out the logistics. Merfyn spent his spring break checking out the course, a committee was formed from local people interested in sailing and Bill Tilman was invited to be the race president.

This was a fortunate choice since it was Tilman who, when the race rules came up for discussion said, “why not let them just get on with it”. There were some rules of course, crews were limited to five, the use of yacht engines was not allowed except when entering or leaving harbour, boots had to be worn on the land sections and no additional transport was allowed.

Seven teams took part in the first race in 1977, and it took those entrants just over 5 days to sail 389 miles, climb the 3 peaks and walk or run 73 miles. Unusually monohulls and multihulls raced together without handicap for the first 11 years. In 1980, HTV made an hour-long documentary about the race, which did much to spread the word; and entries were thereafter limited to 35 due to restrictions in the harbours used. At this time the race finish was moved to Corpach.

After several years the multihulls began racing in their own class and in 1999 the race was restricted to monohulls only. In 2019 Multihulls then returned to the race.

For the sailors, the Race includes many seamanship problems not normally associated with yacht races: the crossing of Caernarfon Bar, the treacherous Swellies in the Menai Straits, the rounding of the Mull of Kintyre, the whirlpools of the notorious Gulf of Corryvreckan, and finally the narrows at Corran where the ebb will stop the boat dead in the water.

Thus, a well-found boat is needed and much meticulous planning and preparation is required for success. Yachts are not designed for rowing and to get the best out of oars, which many boats carry, special fittings are needed. The talents of the runners and the sailors must be combined – teamwork is essential.

The runners, both men and women, include some of the finest fell runners and marathon runners in the country. Generally, marathon runners don’t much care for running up and down hills and fell runners are equally averse to running on roads.

The mountains present problems of their own; there is always snow on Ben Nevis, even in June; wind, rain and mist can make conditions atrocious. Added to which many have to do their running in the dark and for those who suffer from sea sickness they do not even start the runs feeling at their best. The faster the yacht sails the quicker the runs come round. For the leading boats the runners usually have to do the first two stages for one 24-hour period.

The Race is a journey through much of the finest scenery in Great Britain. Barmouth itself lies at the mouth of the Mawddach estuary described by Wordsworth as “sublime”. The Race has attracted competitors from all over the UK, Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Eire, Norway, the United States, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, South Africa, and Australia; and has spawned other 3 Peaks yacht races not only in the UK but also Australia, Hong Kong, and other parts of the world so that today, 3 Peaks Yacht Racing has become a genre of its own.

Every type of yacht has taken part from 88-year-old prawners to expensive trimarans specially built for the race; even the stars of the BBC series ‘Howard’s Way’ – Barracuda of Tarrant and Alien. Gareth Owen, a three-time winner of the race, was a national, European, and world champion in dinghies, when not at work as a Merseyside policeman. Several skippers have skippered yachts in round the world races, and many others have sailed round the world. Robin Knox-Johnston was another past competitor as was Brian Thompson who was said by many to be Britain’s top offshore multihull sailor.

Between 1989 and 2013 there was an Australian version of this event. The course took teams from the northern Tasmanian port of Beauty Point to Hobart in the south. Three sailing legs and three endurance running legs took the yachts and their teams past some of Tasmania's spectacular coastal scenery including the highest sea cliffs in the Southern Hemisphere soaring some 300 metres.

· 90 nm to Flinders Island (settlement of Lady Barron) in Bass Strait where two runners proceed to the top of Mount Strzelecki (65 km run; 756 m ascent);

· 145 nm to Coles Bay where two runners scale Mount Freycinet (33 km run; 620 m ascent); and

· 100 nm to Hobart on the River Derwent where two runners top Mount Wellington (33 km run; 1270 m ascent)

Shackleton and South Georgia

A new young adult non- fiction book has recently been released called “Shackleton’s Endurance” It joins a whole bookshelf of accounts written since the ill-fated expedition which took place over 100 years ago. Most of us know of the extra-ordinary feat of endurance, navigating in open boats across the Southern Ocean to South Georgia but because of the magnitude of that part of the expedition I think the achievement of crossing the mountains, having sailed so far, is of equal substance.

Here’s an account from the Arctic Heritage Trust

Their 16-day ordeal at seal was over, but they were about to face a further challenge …The exhausted six-man crew had reached South Georgia, and Shackleton realised that the boat was in no shape to make a further journey to the whaling stations on the other side of the island. They instead made a shorter six nautical mile voyage to a beach at the head of King Haakan bay, where they beached the James Caird and overturned it into a shelter, which they nicknamed Peggotty Camp after Peggotty’s boat home in David Copperfield by Charles Dickens.

George Marston painting of Shackleton and the JAMES CAIRD landing on South Georgia

Shackleton had determined that the only way they could reach the whaling station at Stromness was to cross the island on foot, a feat that had never been done. It was clear that Vincent, McCarthy and McNish were in no condition to make the crossing, so Shackleton, Worsley and Crean would cross the island and send help for the remaining three. They were ill equipped for such a crossing, wearing only threadbare clothing and boots. They threaded screws through the soles of their boots for extra grip in the snow and ice and to remain nimble they carried only enough provisions for three days.

The trio were delayed from setting out when a storm hit on May 18. By the following morning the weather and cleared and at approximately 3am they set off into the unknown …

At the end of the first day, the trio had ascended 3,000ft and could see Possession Bay to the north. They realised they needed to get to the bottom of the valley before nightfall, which brought devilish fog and rapidly dropping temperatures, spelling certain death. They attempted to cut steps into the ice to make their way down, but Shackleton quickly determined that this was hopeless. He then suggested the unthinkable – they would step off the precipice in front of them and slide down.

They could see very little, and the slope could have easily led to a sheer drop of thousands of feet, but they were out of options. The three men coiled up their pieces of rope into three ‘pads’, Shackleton sat in front, Worsley straddled his legs around Shackleton, and Crean sat behind Worsley doing the same. Without pausing, they launched themselves into the unknown below. In Worsley’s own words:

“We seemed to shoot into space. For a moment my hair stood on end. Then quite suddenly I felt a glow and knew that I was grinning. I was actually enjoying it. It was most exhilarating. We were shooting down the side of an almost precipitous mountain at nearly a mile a minute. I yelled with excitement and found that Shackleton and Crean were yelling too. It seemed ridiculously safe. To hell with the rocks!”

The slope began to level out and their speed slowed to a stop. Worsley estimated they had travelled approximately 3,000ft down the slope in about three minutes. The men shook hands, and Shackleton wryly commented, “It’s not good to do that kind of thing too often.”

After a brief break for a well-earned hot meal, they continued on their way…

Shackleton, Worsley and Crean were exhausted, and their nerves frayed. They had survived their makeshift sled ride down the mountain but were still a long way from Stromness and getting there was largely an act of guesswork. After another six hours or so of hiking they reached the crevasses of a large glacier, however there were no glaciers at Stromness Bay.

They took stock for a moment, huddled together in the lee of a large rock. Shackleton suggested that they take a half hour nap. Within a minute both Worsley and Crean were asleep. Although he was exhausted, Shackleton knew that if he too slept, they would likely never wake up. He waited five minutes before shaking his companions from their slumber to resume the march, telling them that they had slept the full half hour. They made their way toward a gap in a line of peaks, and as dawn approached, they saw the water of Fortuna Bay below and beyond that the mountains that they knew surrounded Stromness Bay. They shook hands once again, a silent celebration of another goal reached. As they prepared breakfast Shackleton thought he heard the sound of a whistle from the whaling station. The three ate their breakfast in silence, listening for the sound. At exactly 7am the whistle sounded again.It was the first sound of humanity they had heard in over a year.

The three men began the descent towards Stromness, with Shackleton suggesting the most direct route. The route became dramatically steep, and they had to cut steps into the ice once again. A blizzard would surely have lifted them off the exposed slope, but the weather held in their favour.

Upon reaching the shore of Fortuna Bay with great difficulty, they proceeded on to what they thought was level ground, only for Crean to break straight through ice into a frozen lake up to his waist. They lay flat to distribute their weight and made their way off the fragile surface.

As they approached the whaling station, in typical gentlemanly fashion, the trio attempted to make themselves presentable, in Shackleton’s words ‘for the thought there might be women at the station made us painfully conscious of our uncivilised appearance.’

They came across two youngsters, the first humans they had seen in nearly eighteen months, who ran away at the sight of them. The station manager, who had entertained them when the ENDURANCE’s crew had first arrived at Stromness, did not recognise them as they appeared on his doorstep. After recounting the details of their ordeal to the manager they were finally able to bathe, an experience that Worsley described as ‘worth all that we had been through to get’.

Frank Worsley and Lionel Greenstreet looking across South Georgia Harbour, with the ENDURANCE below

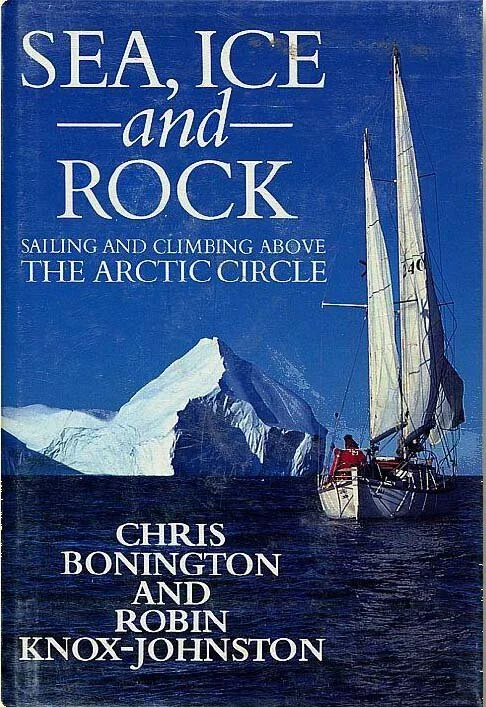

SEA ICE AND ROCK

This is perhaps the most poignant example of how the worlds of stone and water overlap but retain their peculiar qualities.

When leading mountaineer Sir Chris Bonington was researching Quest for Adventure, his study of post-war adventure, he contacted Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, the first person to sail single-handed and non-stop around the world, for an interview. This simple request turned into an exchange of skills, which then grew into a joint expedition to Greenland’s unexplored Lemon Mountains. “Sea, Ice and Rock” is the story of this epic journey.

This 1992 article from the UK’s Independent Newspaper explains their relationship beautifully.

Mountaineer Chris Bonington is best know for scaling the summit of Everest in 1985. He has also pioneered routes in Britain and the Alps and written many books, including Quest for Adventure and Everest the Hard Way. Robin Knox-Johnston began his sea career in the Merchant Navy. In 1968-9 he was the first to circumnavigate the world single-handed, in his yacht SUHAILI He broke the transatlantic record, taking 10 days to reach the Lizard from New York. The two teamed up to sail and climb in Greenland, recording the trip in their new book: Sea, Ice and Rock.

CHRIS BONINGTON: We met on the television programme, The Krypton Factor. I wasn't that fit - I'd just had two ribs out, and I remember looking at the line-up for the assault course and thinking, well, I can see Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the polar adventurer, will beat me. But never mind, I'll come second - after all, that tubby sailor Robin Knox-Johnston will be no trouble] My ego took a dent when Robin shot off like a rocket and came second. I ended up coming third.

In 1979 I was working on Quest for Adventure, a study of post-war adventure. I called Robin to ask for an interview and he said would I like to join him for a sail. I could show him some climbing techniques and he could show me the rudiments of sailing.

It was the first time I'd been on a yacht. We sailed for a while and then anchored. Robin's wife and daughter stayed on the boat, and we paddled to the shore to exercise Robin's skills at climbing. The route was quite difficult, and I was impressed at how steady Robin was in tricky conditions. He just padded quietly along. After a bit we arrived at this huge drop. I asked Robin if he had ever climbed before. He hadn't, so I showed him. When I had finished, Robin very politely asked if he could go down the way he was used to climbing down ropes on his boat. He was used to using his arms. I wanted him to use his legs. I wasn't too happy about it, but he lowered himself down quite safely.

It was during that sail in Skye that Robin and I built the foundation of a very real friendship. His proposal that we should combine our skills on a joint trip to Greenland was just an extension, on a rather grand scale, of our voyage to Skye.

Robin impressed me immensely as a leader. Traditionally, the skipper makes all the decisions. But Robin made a point of consulting everyone before a decision was made. Most of the time, nobody dared to advise him, but it was nice to feel you were part of the decision-making process.

To be frank, I found the sailing trying and very boring. The moments of crisis which we had on the way back were easy to deal with: the adrenalin pumps and you get all worked up. The bit I found difficult was spending day after day in the middle of the sea.

I am a land-lover and not really a do-it-yourself type of person. Robin, in contrast, is a natural sailor and seemed to enjoy monkeying around the engine or mending the lavatory. I was aware that Robin didn't really need me. To be honest, I felt a bit useless at times. I found that very trying. The crew was also packed very close together: six people on a 32 ft yacht, designed to sleep four. At least when you're on a mountain expedition you have a chance to get away from each other.

When we reached Greenland and it was my turn to 'lead' the expedition, I found it difficult taking on the responsibility for Robin's life. There were many instances climbing together when, if Robin had fallen, he could have pulled me off with him. I had to watch for that constantly.

I underestimated how difficult the Cathedral - Greenland's highest mountain - would be. Robin isn't a natural climber, which made his efforts even more impressive. The first time we tried to reach the pinnacle, we were on the go for 24 hours. On the way down we were dropping asleep on 50 degree slopes, 1,500 feet above the ground.

Robin went to hell and back, but he totally put his confidence in me. He just followed. When it got too difficult and I realised we'd have to turn back, he accepted it. I also knew that Robin was worried about the boat: whether we'd be able to get it through the ice, whether it was in one piece. Yet he was behind us having another go at climbing the mountain.

The only time there was a near-crisis was on the yacht on the way home. We were taking it in turns to be on watch. I was supposed to get up at 4am for my shift, but Robin decided not to wake me. He felt he could do it himself. On my previous shift the night before I'd almost dropped asleep. I felt that he didn't trust me - I felt insecure, and I said so. Robin immediately reassured me that I'd jumped to the wrong conclusion.

The very next day we were sailing through an extremely difficult passage. The winds were tricky and once again it was my turn to be on watch. I was aware that if I made a mistake, I could take the mast out, which is horribly expensive and a real nuisance. It was difficult sailing, but I got through. I felt terrific but I also appreciated Robin's faith in me. He'd trusted me with his most precious possession - his yacht.

While we enjoyed the Skye trip, we didn't really know each other until the end of the Greenland expedition. I found that underneath his bluff exterior, Robin was a kind-hearted, sensitive person. While he enjoys company, he is also capable of the most extraordinary solo voyages.

ROBIN KNOX-JOHNSTON: When you're at sea or halfway up a mountain there'll be a point at which you realise that your life is in someone else's hands. An awful lot of Chris's friends have died mountain-climbing, and yet he's still alive. Knowing that I was about to embark on something strange, for which I had no expertise, I needed someone concerned with safety, someone I knew I could trust. When I was with Chris, I felt comfortable when he took charge. He didn't expect me to be an expert. He just wanted me to do the best I could. If Chris said I could climb a surface, I believed him. I knew he was the right person to go to Greenland with.

On board the ship Chris always pulled his weight. I made a point of teaming him up with a very reliable seaman so that he could ask as many questions as he wanted without feeling intimidated. But when we got on land and Chris took over, there wasn't a noticeable difference. He didn't say: 'Right, I'm in charge.'

The time I got nearest to challenging his authority, I was 3,000 feet above ground. I was stretched across a rock, my clumsy great boots on a ledge as wide as your finger. Chris kept saying: 'I've got you] I've got you]' I was on the end of his safety rope, but I could see an awful lot of his feet on the ledge above me, so I thought: 'I'm not so sure he's got me all that well]' I was feeling around for a handhold and suddenly Chris said: 'What are you doing?' I said, 'I'm looking for a handhold.' He said: 'You don't need to - use your legs.' I thought, you may rely on your legs, but as a sailor all I'm able to rely on are my arms.

The views from the Cathedral were like scenes from fairyland: brown mountain tops coated with splodges of snow. Clean, crisp - just beautiful. Knowing that nobody else had been there before gave it a mystical appeal. We were explorers] The only sounds we could hear would be the shatter of a falling rock every 10 minutes or so.

There were difficulties. I was very conscious that, while I could manage if Chris was unable to do his part sailing, he wouldn't be able to get up the mountain if I didn't keep up with him.

At one point I suggested that Chris should go on. He was getting worried about whether we'd be able to reach the top. I felt I was holding him back. 'You go on,' I said. 'I'll stay behind and admire the scenery.' Chris refused: 'You don't split a party up' was all he said.

So I concentrated on watching Chris, trying to memorise where he put his hands and his feet so I could keep up with him. The only thing I can remember thinking was: 'There are 3,000 feet below me. What am I doing here?'

There's a greater warmth in our friendship for having survived the trip to Greenland together. Trust and respect have been tested. We have very different approaches to handling things, but we can slot into each other’s company easily. Our age makes it easier. We're not young people who are perhaps more awkward with each other. We have nothing to prove. -

If you have a favourite story that combines climbing and sailing or perhaps you have had your own adventure then let us know. We’d love to here from you!