“Sail she by da leech, mon!”

Part Two of Duncan Blair’s musings on the joys of the gaff rig.

(Read part one HERE)

My second post of June discussed the advantages and joys of the gaff rig. This post will look at the gaff rig from a different perspective; not the beautiful, big-boned Bristol Channel Pilot Cutters of England or the shoal draft fishing smacks of the eastern United States and the Gulf Coast.

I have chosen to highlight the working sail of the Bahamas, specifically gaff rigged sloops and schooners, all of them traditionally built by hand using local timber. They were rough looking but very capable.

I also want to pay more attention to the dynamics of the gaff sail. To do that I will be calling on a book entitled The Sailmaker’s Apprentice—A Guide for the Self-Reliant Sailor, by Emiliano Marino (see References below.)

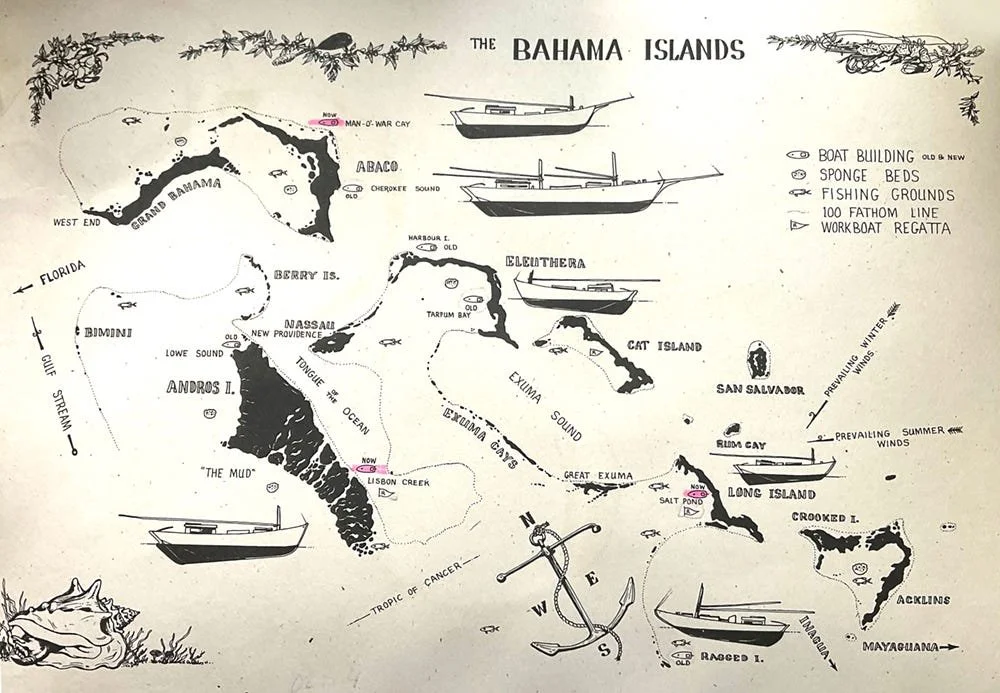

Map of the Bahamian Islands, from the book Bahamian Sailing Craft, by William R. Johnson Jr. (See References below)

Marino boldly states that “There is little doubt that the gaff rig is the single, most versatile, efficient, manageable, safe and sea-worthy rig that has yet to sail the seven seas... From it’s presumed origin in the 16th century Netherlands... the gaff rig went on to dominate commercial sail and yachting into the 20th century. It remains unexcelled as a working rig...” More on this below.

I have chosen this somewhat fanciful map, drawn by the author, because it shows the many islands, cays and reefs that make up the Bahamas. Please note that the anchor serves as a compass rose, that the seasonal prevailing wind arrows are at the 3 o’clock position and that there is no distance scale.

We all remember the importance of San Salvador from elementary school; it is shown just to the West of the prevailing wind arrows. To me, this is an old fashioned map and maybe intentionally so, because it shows us what the map maker finds to be important and I admire him for taking that personal approach.

William R. Johnson Jr.’s map demonstrates just how important working sail was to the inhabitants of the islands, for hundreds of years. In addition to fishing, smuggling and subsistence agriculture, trade—the daily hauling of diverse cargoes, was a vital part of the Bahamian economy that did not and could not rely on a road network. Being surrounded by water had both advantages and disadvantages.

The relatively short distances from the Bahamas to Florida, Cuba and the island of Hispaniola opened up the trading, legal or otherwise, to even more markets.

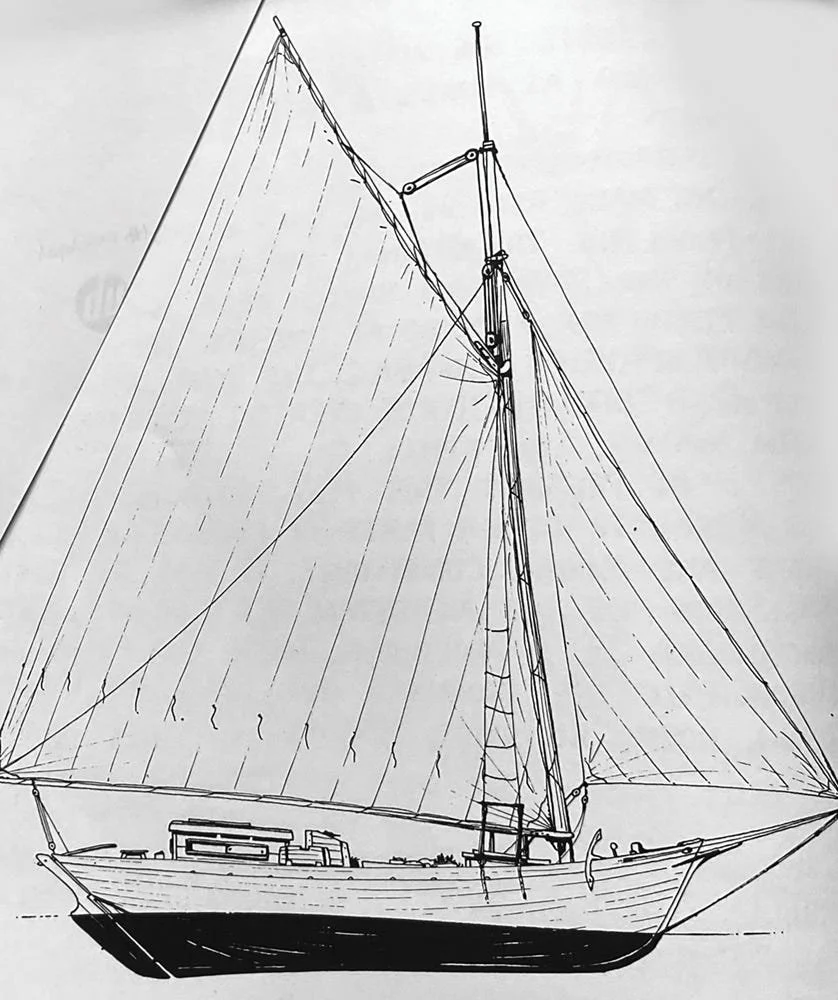

Gaff rigged Smack boat BSC, pg.2

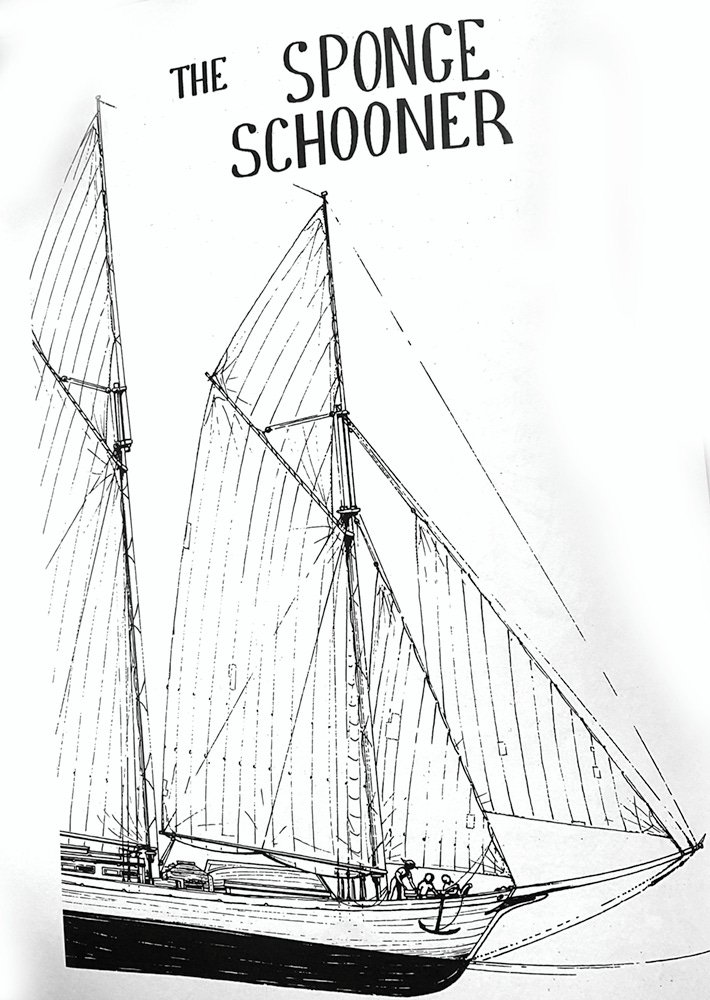

Sponge Schooner BSC, pg. 24

Sponge Schooner running before the wind. BSC, pg.36

Johnson made these sketches in the 1950s and 60s, while cruising the Bahamas in his small ketch, “Island Girl”. The accompanying text is, to me, a simple, honest and useful example of non-academic cultural anthropology.

The drawings themselves are a valuable record of boats, rigs, construction techniques and details of a working sail culture that was still hanging on in the mid 20th century. The description and drawings of the sponge schooners, their crew and methods is worth the price of the book. (I paid $20 for mine several years ago.)

THE GAFF SAIL

Emiliano Marino states categorically that, “Flat is faster and less powerful, Full is slower and more powerful.” I understand this to be a simplified description of the aerodynamics of sails made by a master sailmaker.

Put yourself in the place of a Bahamian skipper whose gaffer is hauling a heavy cargo of mixed goods; timber, people and quite possibly barrels of rum. Which sail type, Flat or Full, would you prefer?

Slowness just might also be considered an advantage when trying to navigate through shoals, sand bars and coral heads. Marino goes on to say “One of the wonderful things about sails is that, for better or for worse, they do not function in one plane. The apparent wind flow may not be the same as the apparent wind aloft—and if not, the sail must be adjusted or trimmed to different angles at different heights.

Given the importance of working sail to the Bahamian economy it is safe to assume used sails that were FULL. Not all of them were gaffers, to be sure. The Bahama dinghy, not a true gaffer, nonetheless has a sail shape that is demonstrably FULL.

Full, as used by Marino, refers to the volume of the sail, created by building in CAMBER; think of the baggy, light air Drifter sails used as light air headsails in today’s sail boats.

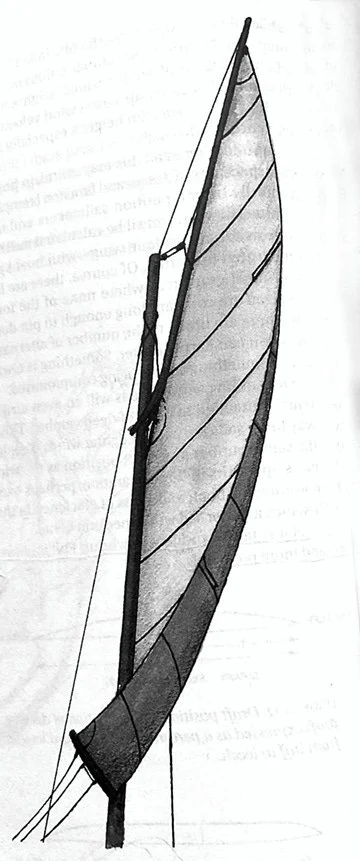

Taken from The Sailmaker’s Apprentice, shows Leech Twist in a gaff sail.

Marino’s caption for this drawing states, “The true wind is often stronger aloft and the apparent wind angle is therefore farther aft, so some twist may be desirable. Too much twist is to be avoided, however.”

A gaff vang is the prescribed, but seldom used, way to avoid or at least reduce gaff twist. To do this it would be attached to the aftermost end of the gaff and brought down to the after deck to be belayed, or possible led a short distance forward through a turning block, allowing it to be more conveniently handled and belayed from the cockpit.

The existence of True Wind (TW) and Apparent Wind (AW), as well as their importance to the aerodynamics of sailing is well known, especially in the contemporary sailing world of racing hydrafoils capable of doing 50 knots.But the point of this post IS NOT that TW and AW exist, while moving around, back and forth, along the surface of the sail.

The point of this post IS, emphatically, that the complex interplay of wind, sails, hull shape and water have been understood for centuries by ignorant, but not stupid, working class seamen with little or no formal education; people who have grown up and lived all their lives in cultures and societies where working sail was commonplace. There are many examples of this but I will simply mention Phoenician seafarers in the Middle Sea, the Mediterranean and the Lapita seafarers/explorers of Indonesia and Polynesia.

The daily use of and dependence upon working sail inevitably created a huge body of experience-based knowledge and “folk wisdom” about all aspects of sail.

About five years ago I was reading some comments made on-line in the Woodenboat Forum. One of the participants told of being on the Caribbean island of Antigua- not all that far from the Bahamas-at a classic boat regatta. What caught my eye was his story about a grizzled Antiguan sailor, on a gaffer, who yelled across the water, while sailing, to a sailor at the helm of another gaffer.

The words yelled across the water were: “Sail she by da leech, mon. Doan choke she. Let she breath!”

I think that those twelve words shouted across the water to another boat are a quintessential example of the prosaic folk wisdom of traditional working sail. As such, the knowledge was not learned by reading books, or going to class or watching Youtube videos.

To be sure that the vernacular words are clearly understood, I offer my own translation:

She means Her

Doan means Do Not

Da means The

Mon is probably best understood as “Dude”in modern parlance.

This results in”Sail her by the leech, Dude. Do not choke her. Let her breath!”

My interpretation of the meaning is this; Be Aware!, Listen to what the sail shape is telling you.

Do Not oversheet, Slack off on the sheets.

Trim the sails to optimize Fullness, then allow the Fullness to help you find the “Sweet Spot” of Power.

I understand these twelve words to be an offer of advice, based on the collective experience of centuries. We should all be so lucky as to have such advice given to us.

PAU

As always, all ideas and opinions stated above are mine alone.

REFERENCES:

Bahamian Sailing Craft, Notes, Sketches and Observations on a Vanishing Breed of Workboats, by Willian R. Johnson, Jr. Second edition, Tortuga Productions, 2000.

The Sailmaker’s Apprentice, A Guide for the Self-Reliant Sailor, by Emiliano Marino, McGraw Hill. 1994.