schooner henrietta

THE MAGIC of PARALLEL LIVES

Schooner Henrietta on Domain Slip Hobart 1939. The Maritime Museum of Tasmania

In 1941, the ashes of a master mariner from Massachusetts were scattered at sea over the shipwreck of his schooner in Port Phillip Bay. The site is the mile wide reef extending off Point Cook just 7nm from Williamstown, his destination. He had sailed with his wife from Cape Cod to Sydney arriving in 1938. A Russian émigré also arrived in Australia that year. His ashes were scattered at the same location in 2014.

Before being lost on the Point Cook reef in 1940, the magic of the Grand Banks schooner HENRIETTA, brought these two people together. Pete Sawyer was the American owner and captain and Jules Feldman at a loose end in Sydney, joined the crew. Both remained in Australia by circumstance, one making significant sacrifice to the war effort and the other surviving to make an important contribution to sailing journalism and publishing.

View of Port Phillip Bay looking south with Point Cook below Altona Bay

PETE & DOROTA SAWYER

Captain Bailey (Pete) Sawyer was a master mariner growing up in Cape Cod Massachusetts after the first world war. He went to sea as a young man on merchant vessels travelling across the Pacific to Hong Kong and Helsinki through the Baltic. He enrolled in the New York Nautical School where training was on traditional square-rigged ships. After graduating in 1927 with a specialty in gyroscopic compass navigation, Pete made several arctic survey trips along the Labrador coast in a schooner called ARIEL where he was first officer and eventually the ships master.

Pete married Dorota Flateau, an Aussie girl from a farming family near Apsley in Western Victoria. Together they purchased HENRIETTA, the 112’ LOA and 22’ beam Grand Banks fishing schooner with plans to refit her and sail to Australia. These schooners were famous Canadian and American deep keeled working boats. They were designed for commercial cod fishing and fast sailing to the Grand Banks off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. The design of Errol Flynn’s ZACA was based on a Grand Banks Schooner. See SWS HOBART to HOLLYWOOD 3rd June and ZACA & the FISH 9th June 2021.

Henrietta with her square yard sail by Jack Earl. Courtesy Feldman family

With expectation of Pacific winds and currents predominantly from east to west, the Sawyers refined the schooner rig using Pete’s knowledge of square-riggers. They extended the topmasts to carry larger topsails and added a bowsprit to carry the staysails and jib further forward. This allowed for a square sail set below a yard with triangular “raffees” above for downwind sailing in light air. The HENRIETTA could now carry 7,000 sq ft of sail. Below decks the fishing holds and bunks for 20 crew were converted for cruising, adding a main saloon and comfortable staterooms.

In August 1937 Captain Pete Sawyer, his Australian wife Dorota and a crew of eleven, set sail on HENRIETTA from their homeport in Truro, Cape Cod Bay. Dorota was an accomplished navigator and charted an Atlantic route south through the Strait of Magellan in Chile to the Pacific. They turned north with the Humboldt current to join the west flowing South Equatorial flowing to the Australian coast. In October 1938, after 14 months at sea, they arrived in Sydney and continued down to Melbourne to meet family.

Dorota and Captain Pete before departure 1937. Phipps Family Collection

Dorota taking a sun shot in the Pacific 1938. Phipps Family collection

INVITATION to a FISHING CRUISE

While the Sawyers were sailing across the Pacific to meet family in Victoria, Jules Feldman was studying in Shanghai. By November 1938 he sought refuge in Australia from the Japanese military occupation of China. Sydney University did not accept his qualifications to continue his studies so he answered an invitation to join HENRIETTA on “fishing trips” to Tasmania and the Barrier Reef in 1939. He hoped to remain with the schooner and get to America on the Sawyers return voyage but remained in Australia, becoming a journalist and later an important magazine publisher.

Invitation to crew published in Australia. Phipps Family collection

EAST COAST SURVEY

Pete’s experience of arctic survey work on the ARIEL secured commissions for HENRIETTA while in Australia. In March 1939 she completed a 3 week scientific and survey trip of the Furneaux Group in Bass Strait for Melbourne University. These islands are well known today as Flinders, Cape Barren and Clarke Islands. HENRIETTA then sailed on to Hobart for maintenance knowing they would be spending 3 months from May on a hydrographic commission along the Great Barrier Reef.

Henrietta on Domain Slip Hobart 1939. The Maritime Museum of Tasmania

The purpose of the second trip was far more serious than the fishing trip they advertised. The Australian government was following the expansionary interest of imperial Japan after the invasion of China in 1936. Japanese merchant vessels and fishing boats, crewed by disguised naval officers were regular visitors along the eastern seaboard. They were documenting coastline, navigation passages, anchorages, lighthouses and fortifications. With few detailed maps available of the large Australian coastline, HENRIETTA was commissioned to investigate and extend the limited charts of the Barrier Reef. Some say these were no more advanced from Cook and Flinders own charts.

Using a small flat bottomed motor launch lowered from the deck, the Sawyers documented at least ten new navigable channels through the reef. They arrived back in Sydney in September 1939 to find their plans for a return voyage to America would change with the declaration of war. After a short time in Sydney HENRIETTA was brought south to Geelong.

HENRIETTA’s WAR

The Sawyers offered the schooner to the Australian Navy but it was declined. However, the Port Phillip Sea Pilots were considering it as a pilot vessel. In preparation, Pete organised to bring the boat from Geelong to Williamstown for dry-dock maintenance with three mates from the Air Navigation School in Laverton.

A half-day 35NM motor-sail to Melbourne is a regular passage for Port Phillip Bay sailors. Some 150+ boats made the same trip from Geelong’s Festival of Sails only last weekend. On the 28th September 1940 HENRIETTA departed Geelong without the Port Phillip Bay charts on board. The Sea Pilots had removed them for review and updating.

After leaving the Hopetoun Channel near Portarlington, HENRIETTA stood well out, taking regular depth soundings and enjoying clear weather and good visual sight of the low lying western shore. After Werribee, the crew could clearly see the line to Point Cook, Altona and Gellibrand. Soon an unexpected southerly change came through bringing heavy rain squalls and a lifting wind, driving the schooner to the lee shore. The weather blocked visual sight of the very flat landscape and any markers, especially the red can-buoy (Dumb Joe) at the eastern end of Point Cook reef. Peter Taylor describes the situation onboard;

“Slightly worried about the lack of vision over the bay, the tension on the schooner eased up as the crew sighted a ship unloading at the Explosives Pier south of Altona. The vessel, they assumed, would be in a safe depth of water, so a course was set towards it. What the HENRIETTA’s experienced skipper and navigator didn’t realise, because of the missing charts, was that the Point Cook reef extends east for a mile offshore. This put the reef directly between the schooner and the vessel unloading explosives. They were still travelling at 6 knots, in what they thought to be deep water, when she ran aground on the reef around 5pm. HENRIETTA drew 13 feet of water while the depth over the reef at the time was 8 feet. An ebbing tide and increasing wind ensured she was stuck fast and trapped”.

Henrietta stuck fast on Point Cook reef 1940. Phipps Family collection

From the Harbour Masters Report, the alarm was raised and the Harbour boat No 3 left Williamstown’s Anne Street pier at 19.30. After rounding Gellibrand point they encountered heavy seas and rain squalls but reached Point Cook by 20.30. They could not locate HENRIETTA in the failing light against the “loom of the trees” and returned. They sailed again the following morning with the Ports and Harbours launch VICTORY reaching the schooner at 11.30. The crew had survived overnight onboard, knowing she was severely damaged and taking water. The rescue boat “embarked the owner and three other men about 00.30pm”.

Brett Hilder, one of the crew described their long cold night in his Navigator in the South Seas, published 20 years later;

We tried to get her off by going astern, we laid out the anchors to seaward, and passed a message ashore by a launch for a tug to try to get us off at about 9 p.m. when it would be high water. In the meantime the wind increased to a gale, being part of a cyclone and the ship was driven further on to the reef.

About dusk she suddenly filled with water and the seas started to break heavily over her. It seemed likely that she would shake down her masts and spars as she broke up, so we launched the two little dories over the side and secured the painter. One of them broke adrift in the rising seas, and the other, which contained our good uniforms and cameras, was filled by a wave which broke right over the hull. I went over the side to save the gear and found the water nearly freezing, as it was midwinter. After the gear was saved, the dory capsized and broke adrift; both dories were picked up five miles along the coast, which was disturbing news for our waiting wives.

I was all for swimming ashore while we still had some strength, but we were failing rapidly from the cold, the lack of food, and our exertions. During the long stormy hours of the night we lit distress flares, but without any effect, and we finished the night in the main rigging wrapped in a sail to keep out of the freezing seas. We were finally picked off the bowsprit at noon the next day by the same launch we had spoken to the day before, manned by a stevedore from the explosives anchorage at Altona. We returned to work next day very sad at the loss of the ship, which was the apple of Pete’s eye and he had to sell the broken hull for £10. Only three months later Pete was himself killed in a crash and, later, our C.O., Dal Charlton and I had the sad job of scattering his ashes over the site of the wreck.

The schooner was considered unsalvageable and abandoned. HENRIETTA had survived 20 years in the dangerous waters of the Grand Banks, then a 20,000NM voyage to Australia only to found within sight of Melbourne on a shallow reef off Cheetham’s saltworks (Mermaid brand) at Point Cook. The captain was an experienced seaman and navigator, let down by an unfortunate oversight in preparation and the always unpredictable Port Phillip weather. Fair warning to sailors using Navionics and weather models.

Looking north across Altona Bay from Point Cook today. Photo Goinferalonedayatatime

PETE SAWYER’s WAR

After the Barrier Reef trip, Dorota returned to her family’s farm in western Victoria. A baby girl was born to Pete and Dorota in Melbourne’s Mercy Hospital in December 1939. Pete volunteered for military service, despite America not yet joining the war. He enlisted in the RAAF in July 1940, training flight navigators at Laverton near Point Cook, earning his pilot’s wings, before being transferred to a Navigation Unit in Parkes NSW. Exactly 4 months after the loss of HENRIETTA, Pete was being transferred as a medical patient from Parkes to Mascot. His Avro Anson crashed in the Blue Mountains 60k west of Sydney, killing Pete and the four airmen onboard. That same week his schooner was finally broken up during a severe storm in Port Phillip Bay.

JULES FELDMAN

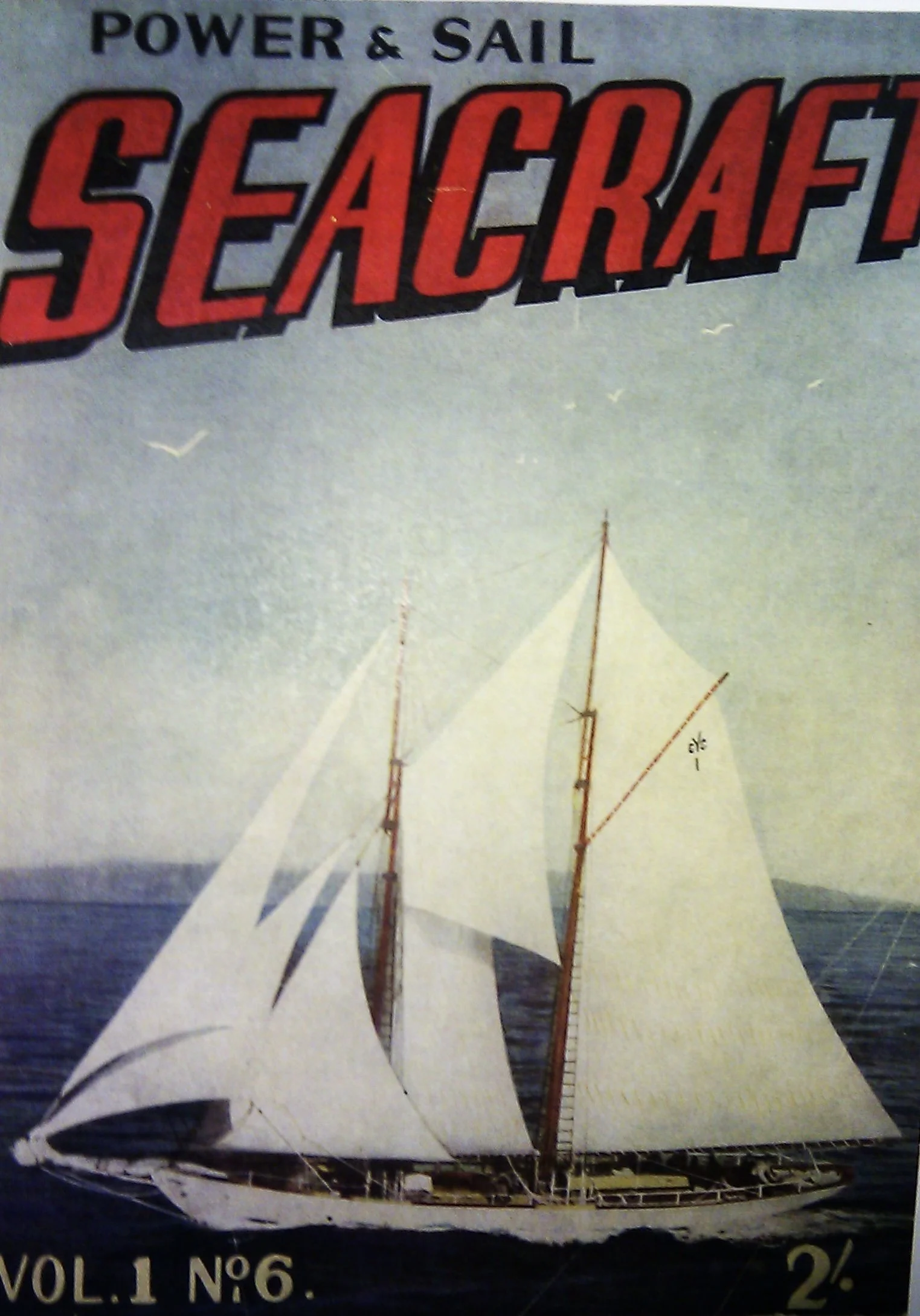

Jules always said his 6 months sailing on HENRIETTA with the Sawyers in 1939 was the making of him. The rejection by Sydney University set him on a new path. He developed a love of sailing and met people Like Lou d’Alpuget and Jack Earl who became important colleagues in the post-war sailing community. Jules never lost his love of the schooner putting a stylised image on an early cover of Seacraft magazine. Sandra, Jules’ wife, generously allowed us to publish the wonderful painting of HENRIETTA done by the marine artist and sailor Jack Earl, a long-time friend of Jules.

Henrietta on an early cover of Seacraft. Peter Costolloe collection

Sandra scattered Jules’ ashes over HENRIETTA in March 2014. Her edited obituary here is a wonderful read. Like Pete Sawyer, she reveals a young man who ended up in Australia by circumstance of war, but stayed and made a real contribution to sailing.

“Born in Siberia in 1919 of Russian parents, Jules Feldman spent his childhood in China and Paris. In Shanghai he had completed two years of an arts course at St John's American University (assoc. with UCLA Berkeley) when the Japanese occupied the campus. A vitriolic letter from Jules to the China Daily News was discovered and his investment-banker father asked Cecil Bowden, the Australian Trade Commissioner, to support his application for a student visa. He arrived in Australia in November, 1938. His intention to continue study failed when Sydney University refused to accept his baccalaureate and UCLA acceptance letter, stating matriculation was an essential entrance qualification.

So Jules joined the crew of the Henrietta, a schooner out of Massachusetts on a world cruise. His intention to apply for a work visa in South Africa or the US failed when the Henrietta turned around in Cairns with the pregnant skipper's wife, arriving back in Sydney on September 3 to war in Europe.

A friend's successful appeal to Prime Minister John Curtin gained Jules permanent residence. Living aboard Henrietta in Rose Bay (Sydney), he was befriended by Lou D'Alpuget, who offered him a job on The Daily Telegraph reporting the 18-footer racing.

After war service as an aircraft fitter, then a year in Vanuatu logging for Pacific reconstruction, Jules returned to the Telegraph in 1946. In 1948 he joined Hudson Publications as managing editor for Seacraft and Outdoors & Fishing. When Colin Ryrie joined Hudson as advertising manager, together they produced the first 11 issues of Wheels before starting out on their own.

On Monday March 22, 1954, in an empty office in Bridge Street, Sydney, Jules Feldman, 35, and Colin Ryrie, 24, formed their company Modern Magazines Pty Ltd launching their new magazine Modern Motor.

The post-war 9 million Australians were experiencing a car shortage. Most motorists drove used cars and did their own repairs. Roads were abominable, the Hume Highway a narrow pot-holed bitumen strip with one-lane bridges. The average weekly wage was $30 and a Holden cost $2046.

Hearing of another motoring magazine in the pipeline, the race was on to hit the stands. Jules' formula, reflecting foresight and diversity, went on sale on May 9, selling a record 50,000 copies.

Determined their monthly magazine would be first with news and tests, they approached GMH in May 1956 for details of the rumoured first new Holden since 1948. When GMH denied all knowledge, Jules and Col entered Pagewood in greasy overalls and took "scoop" photos - selling 90,000 copies. Modern Motor scooped every car model made in Australia from then on.

When Ford flew Jules over the You-Yangs proving ground for the official opening, he sketched an entry point to spy on preview models. In February 1972 they scooped the complete range of Falcons.

In 1965 Modern Magazines began an extraordinary expansion, launching Modern Boating, Australian Cricket, Australian Golf, Australian Motor Cycle Rider, Hi-Fi Review, Rugby League Week and Electronics Today. Movie magazine, Audio Trader and Australian Camera were all launched before Jules retired in 1975, following the tragic death of Colin Ryrie three years earlier.

Jules, a thorough gentleman, always breaking news but never a confidence, leaves behind a huge body of work, a multilingual library indicative of his wide interests, a fascinating autobiography, an anthology of poetry, legions of former readers and a loving family and friends”.

MEMORIALS

Epiphany mural in St Mary of the Harbour MA. Robert Douglas Hunter

HENRIETTA’s name board (from the bow) is at Altona Homestead Museum. Her rudder was recovered and displayed in a Melbourne restaurant (now lost).

Pete Sawyer’s ashes were scatted over the site by Squadron Leader Arthur Charlton and Flight Lieutenant Brett Hilder, two of the crew who survived the reef. Hilder later published a book Navigator in the South Seas that included his sketches and experience on HENRIETTA.

A memorial to Pete is in St Mary of the Harbour at Provincetown, Cape Cod Bay. This little shingle church celebrates local seafarers and artists with beautiful murals and a wall plaque of Mary cradling a Grand Banks schooner.

Jules Feldman’s wife Sandra arranged for his ashes to be scattered on the sea above HENRIETTA at Point Cook reef in 2014.

Sketch of the long night with Henrietta’s bow stuck fast. Brett Hilder

CREDITS

Peter Taylor for his research and pamphlet The Wreck of the Henrietta. Self-published in 2006

The Phipps family are custodians of the Sawyer Collection. Photos Peter Taylor.

CYAA’s Peter Costolloe assisted Sandra with Jules’ ashes and SWS with generous information for this story

Navionics location of Henrietta for scattering JF’s ashes 2014. Image Peter Costolloe