Tsumanis in Sydney Harbour

by John Jeremy from the newsletter of the Sydney Amateur Sailing Club

An undersea volcano erupted in spectacular fashion in Tonga on Jan 15th -Japan Meteorology

The morning of Sunday 16 January dawned with the prospect of another beautiful day on Sydney Harbour running the Sunday series races in CAPTAIN AMORA, a task much enjoyed by the race management team. This day was, however, different.

There was a current tsunami warning as a result of the enormous volcanic explosion and eruption in Tonga. People were advised to keep clear of the shoreline and be aware that there could be strong currents and unexpected eddies. Indeed, the night before, tsunami surges had been recorded on the coast of NSW and there was the possibility of more for some hours.

SASC Committee Boat CAPTAIN AMORA- Image thanks to SASC

The tsunami and air blast from the volcano were felt all around the Pacific Rim and, indeed, the world. In this day and age the SASC has a management plan for just about anything, but not for tsunamis. Even during the 2000 Sydney Olympics we had a Whale Management Plan but no Tsunami Management Plan.

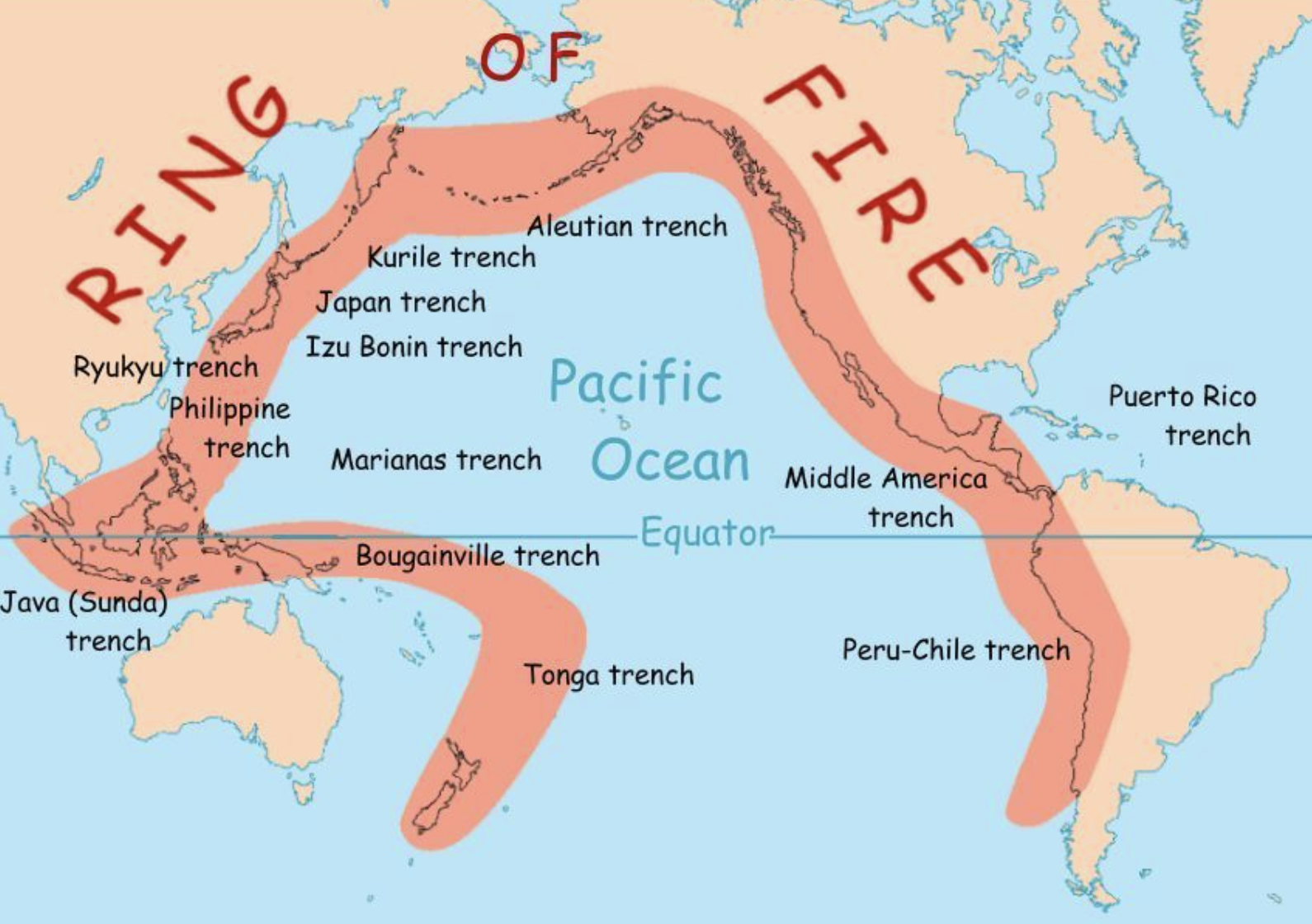

Tectonic plate boundaries some 8,000 km long lie to the east, northeast, north and northwest of Australia and all are capable of generating tsunamis affecting the coast of Australia. Tonga lies directly on top of one of these boundaries. Tsunamis are usually generated by earthquakes in these subduction zones — tsunamis generated by volcanic explosions are unusual but have proved devastating in the past, like the eruption of the Indonesian island Krakatoa, located in the Sunda Strait, which occurred in 1883. It has been postulated that a violent eruption of Krakatoa in 535 resulted in global climate change for several years with crop failures, famine and millions of deaths worldwide. Australia has been affected by tsunamis 55 times since European settlement including seven this century, the most recent in March 2011 following the Tōhoku earthquake in Japan. They were generated by events as far away as South America, Japan and Alaska, as well as closer locations like New Zealand and Indonesia.

The Ring of Fire is a string of volcanoes and sites of seismic activity, or earthquakes, around the edges of the Pacific Ocean.

One of the biggest occurred on 23 May 1960. The Valdivia earthquake in Southern Chile occurred on 22 May and was the largest earthquake yet recorded at 9.4 to 9.5 on the moment magnitude scale [1]. The tsunami generated by this event arrived on the NSW coast on the morning of 23 May. I remember it well — I was in the ferry KOOLEEN on the way to work on Cockatoo Island when the tsunami arrived in the harbour. The ferry was attempting to berth at the Greenwich Point wharf as strong currents were producing large wakes around the wharf piles. KOOLEEN finally managed to secure alongside (with only one line, as was the usual practice) when the current reversed swinging the ferry away from the wharf and breaking the mooring line. After some manoeuvring, KOOLEEN was finally secured.

MV KOOLEEN in 1983 off Greenwich wharf- Photo Hippomenes

I seem to recall that during the event the water level in the harbour rose and fell about two feet in some 20 minutes. The speed of the current observed in the harbour February 2022 ranged from 6–30 knots depending on location. The largest reported current, 30 knots, came from Iron Cove near Balmain and The Spit in Middle Harbour [2]. On Cockatoo Island there was concern that the surge would flood over the entrance of the Fitzroy Dock, which was empty but unoccupied at the time. The extraordinary event at the Hunga Tonga–Hunga-Ha’apai volcano must surely remind us that it is prudent to take tsunami warnings seriously. Perhaps the SASC needs a Tsunami Management Plan after all.

1. The Moment Magnitude Scale was devised in 1979 and is the authoritative magnitude scale for ranking earthquakes by size. It is similar to the Richter scale devised in 1935.

2. Measurements and Impacts of the Chilean Tsunami of May 1960 in New South Wales, Australia, State Emergency Service, 2009.