Well Written - Part III

In this third of our six part of our series on underrated maritime texts, we bring you the final chapter of one of the great voyaging stories, “The Cruise of the Teddy”

Its sad finality, will haunt anyone who has owned and loved a sailing vessel.

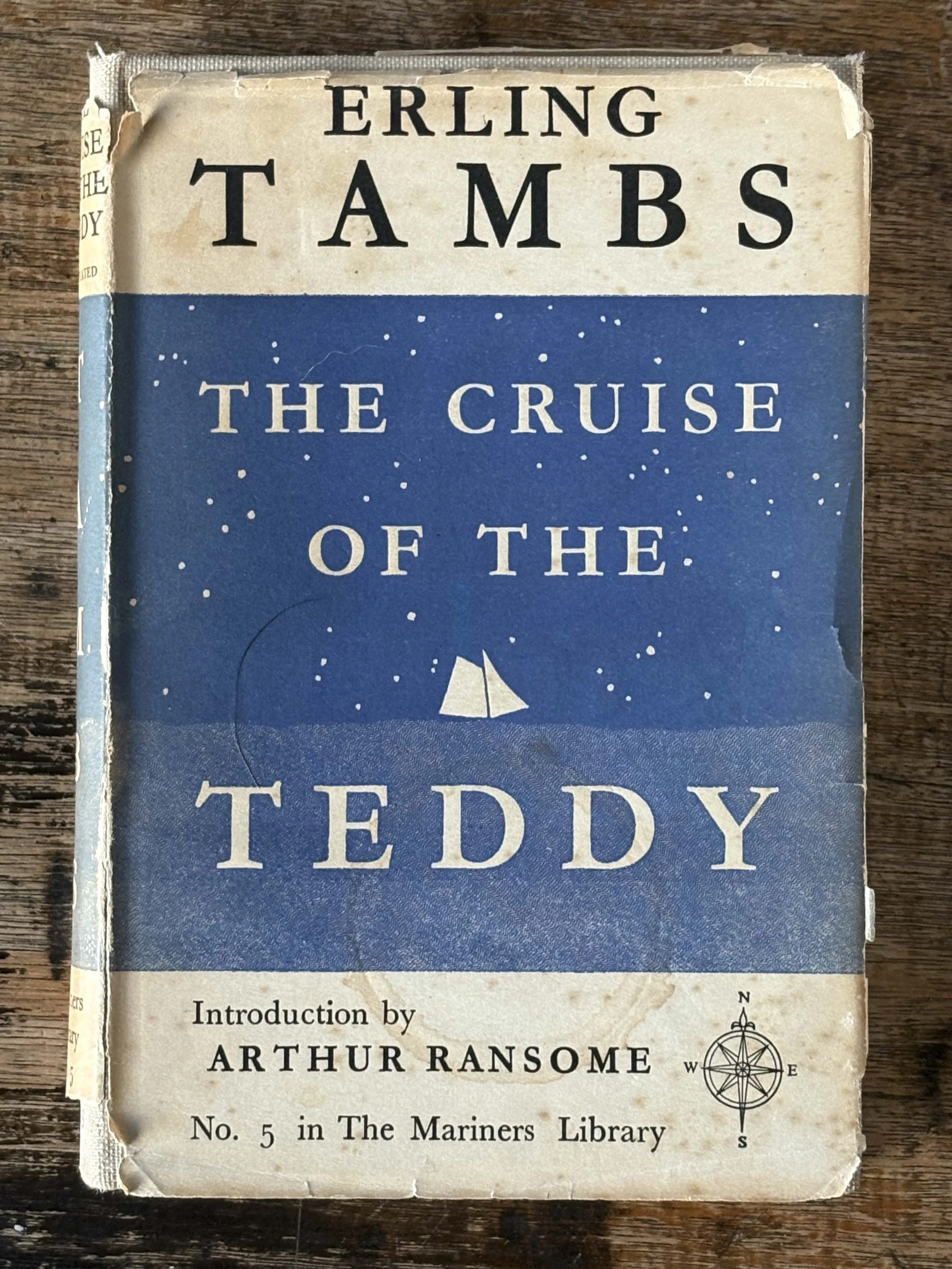

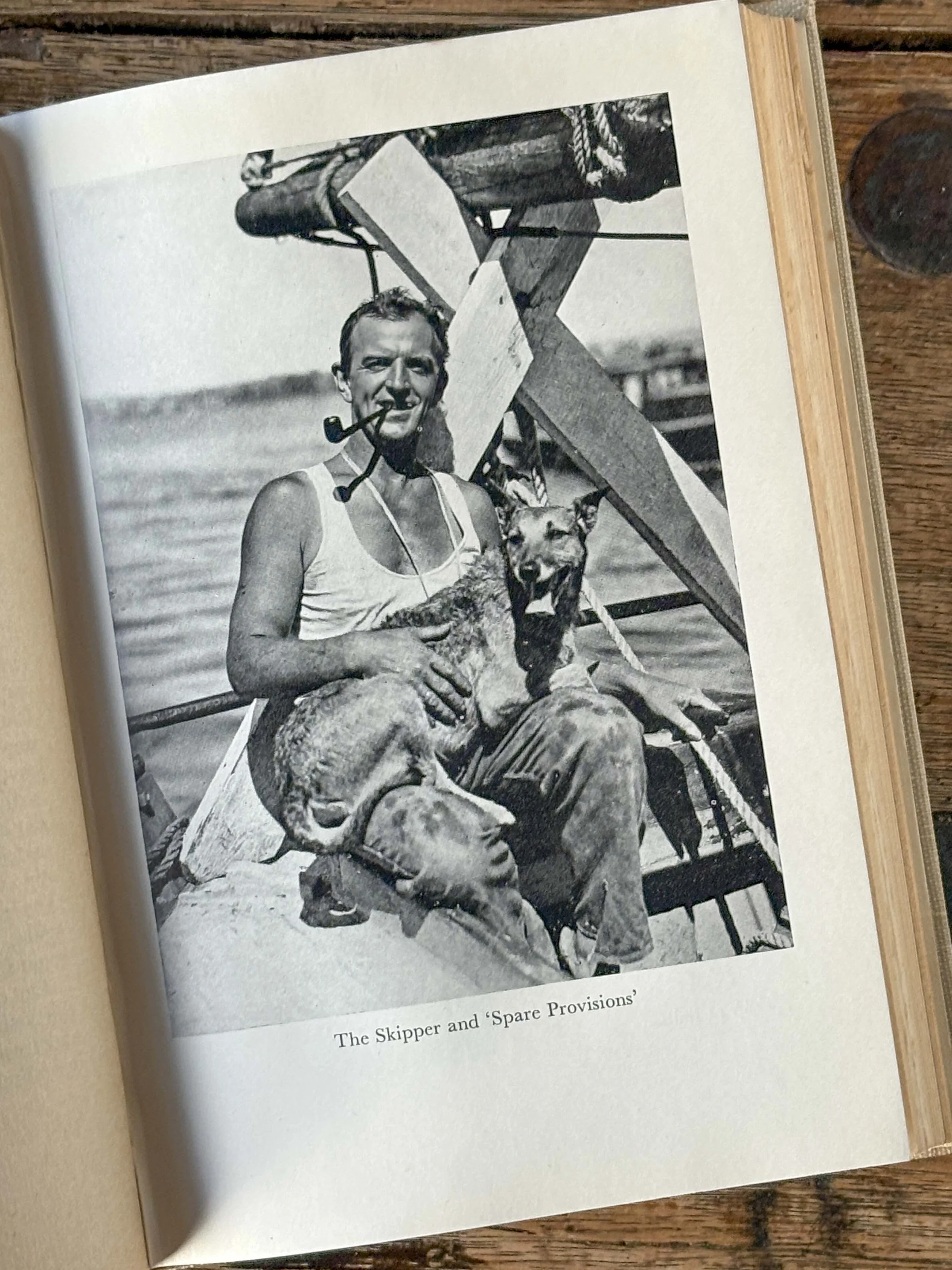

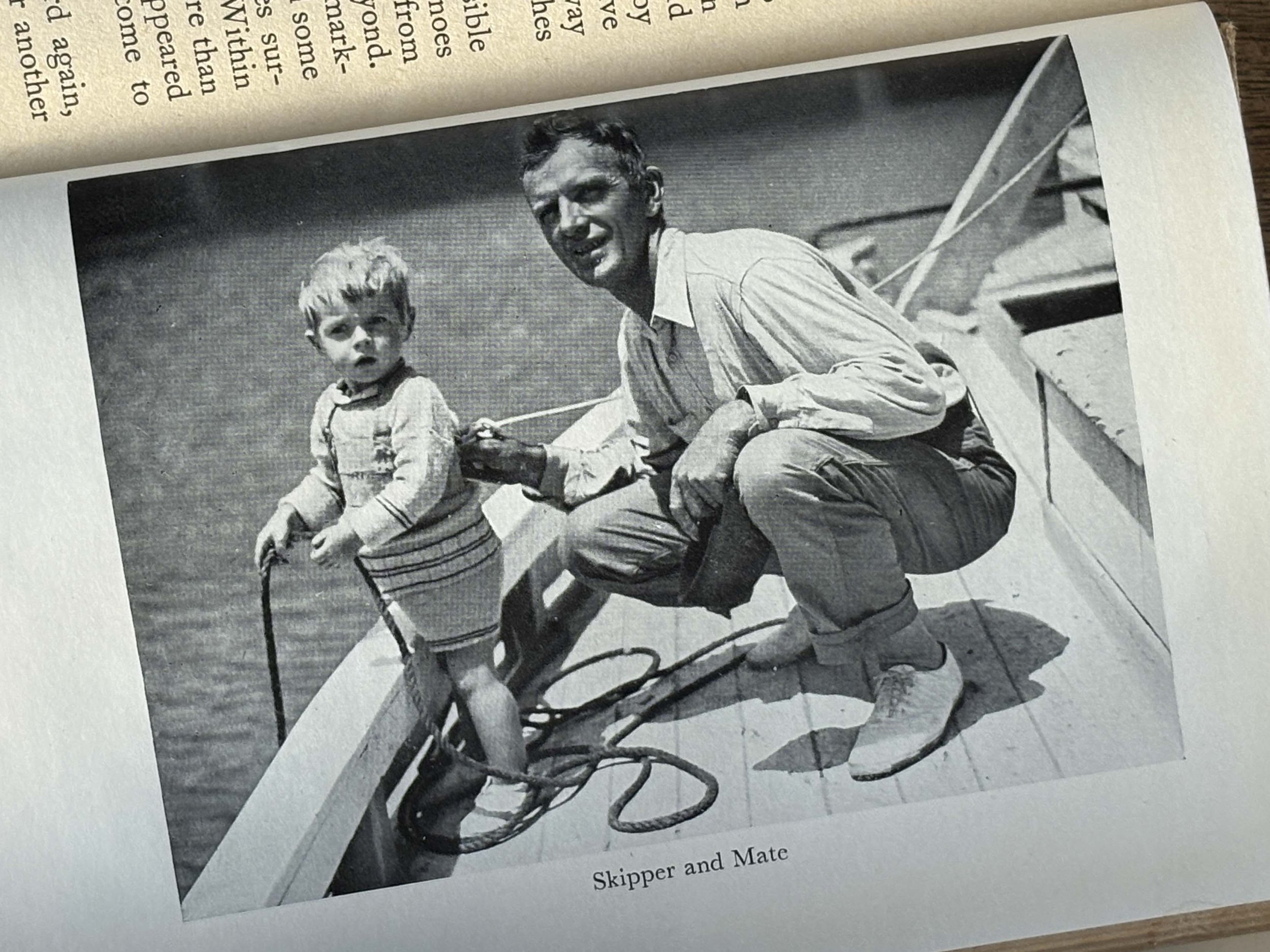

Erling Tambs was born in 1888, in Larvik, Norway, the sixth child in th family. Tambs lost both his father and a brother in a sailing accident, an event that might have put a lesser person off the idea of going to sea. Following a stint as a merchant seaman, in 1928, shortly after marrying Julie Jørgensen, they left Norway in the, TEDDY, a Colin Archer-designed pilot cutter, on a journey around the world. They took a dog known as “Spare Provisions”. Tambs’s voyage wasn’t just sailing expeditions—they were part of a broader lifestyle rooted in adventure, exploration, and writing. His children were born along the way; Tony, in the Canary Islands and daughter Tui, in New Zealand, where his adventures ended.

CHAPTER XXIX - Teddy's Last Voyage

The farewells were over.

We had cast off the last mooring rope and shaken the last friendly hand. Slowly, very slowly we glided away from the boat steps. A navy pinnace offered to tow us past the harbour wharves. When, after belaying the tow-rope, I again turned my gaze towards the landing stage, I saw that the crowd on the wharf was thinning out. Perhaps a score of friends still kept on waving: Mick- Jim -Nurse- Brownie- Cobs- Gibbie - Fred

I suddenly felt a pang of regret, as I realized that should probably never see again those lovable people who had favoured us with the rare and precious gift of their friendship. Yet, I could not stay. I am not made to live in a well-ordered community for long. I am a wanderer....

"It's like a book, I think, this bloomin' world,

Which you can read and care for just so long,

But presently you feel that you will die

Unless you get the page you're readin' done,

A turn anther-likely not so good;

But what you're after is to tune 'em all.'-KIPLING

More than thirteen months had elapsed since we first entered the harbour. Many times since then had we sailed in and out, on the Trans-Tasman Race, on our cruise to Tonga, many times. On the whole they had been thirteen happy months.

Now TEDDY cut her furrow through the waters of the Waitemata for the last time. To starboard arose the well-known cone of Rangitoto, visible from seaward at great distance. To port the sunny splendour of Cheltenham Beach glided by. We tried to pick out the trees sheltering the little house which had been our home for four months. Bathing maidens waved their towels in farewell.

Rangitoto Beacon sped by. Three hours later we sailed through the tide rip in Whangaparoa passage, and as dusk settled upon the surroundings it began to blow from eastward. TEDDY rolled.

The cabin was flooded with farewell presents; in the galley paper bags and packages of stores tumbled about. They should have been emptied into boxes and tins and properly stowed before we want to sea. ln the bustle of farewells we had found no time for such details. Truly, we were hardly ready for sea. Also we were tired. We decided to run into Mansion House Bay at Kawau for the night.

Kawau is a beautiful little island some thirty miles from Auckland and a favourite goal for week-end excursions. There is a little pier in Mansion House Bay, alongside of which I could moor the boat without going to the trouble of anchoring. This latter was as essential consideration, seeing that the anchor was securely lashed in the forepeak and the chain stowed away in the stern.

When, about ten at night, we made we made TEDDY fast to the pier, it was pitchy dark. Kawau had gone to sleep.

Rising the next morning we found that the easterly had developed into a hard gale from NE. We were in no particular hurry to get to Brisbane, our next destination, so, instead of roughing it outside, remained in the sheltered comfort of Mansion House Bay.

For three days the gale lasted, but by Wednesday morning, the 9th of March, it had exhausted itself and we departed. Leaving the shelter of the cove, found a disappointingly light breeze of southerly wind blowing outside. The tides were at their maximum, running strongly northward and setting us backwards almost as fast as we could beat to windward against the light wind.

However, after several hours of sailing, we contrived to weather the reefs and thence lay south of Kawau, heading well to windward of the southern point of Challenger Island, little rocky islets quarter of a mile long in a north and south direction which is separated from the south-east end of Kawau by a narrow channel

The gale had left heavy swell, which broke thunderously over the rocky ledges of the point.

The breeze seemed to freshen a little as we were approaching these rocks, but the tide was setting strongly to leeward, so that when we were within hundred yards off the point, it was obvious that we could not weather it. The point then lay east of us and TEDDY headed SE. I therefore put the helm down order to go about.

Strange! She would not obey the helm. The wind had suddenly died out. However, TEDDY was still moving ahead; she still had sufficient headway to respond to the rudder, and there was no sea. Here, on the western side of the point the water was almost smooth. Smooth indeed, abominably smooth! Glassy, like the polished surface of a river, where it hastens towards precipice.

I tried again - drove the tiller hard to leeward, again and again. No response! Consternation seized me: the current had TEDDY in her power! With accelerating speed we were driven towards the point, on the other side of which the swell rose to gigantic breakers, which, hurling themselves against the rugged obstacles with thundering fury sent rumbling waterfalls of foam over the rocky ledges. Sunken rocks off the point showed their frothy fangs, thirty, twenty yards away. The tumult was deafening. Oh, how I hated then, those rocks, these breakers, those snarling fangs, threatening, sneering, evil, inevitable….

I rushed forward and ran out the heavy sweep, tore and pulled and rowed with impotent rage. My wife cast off the halyards. The sails came clattering down.

Like a mill-race the current swept round the point.

Then the sweep broke.

I grabbed the spinnaker-boom in a foolish attempt to stop a weight of twenty-five tons driven onwards at five knots’ sped. A desperate man will do stupid things.

Now we were close against it. We felt the lift of the surge. Cold breaths of moisture-laden atmosphere chilled us. My heart shrank within me. TEDDY’s end was near.

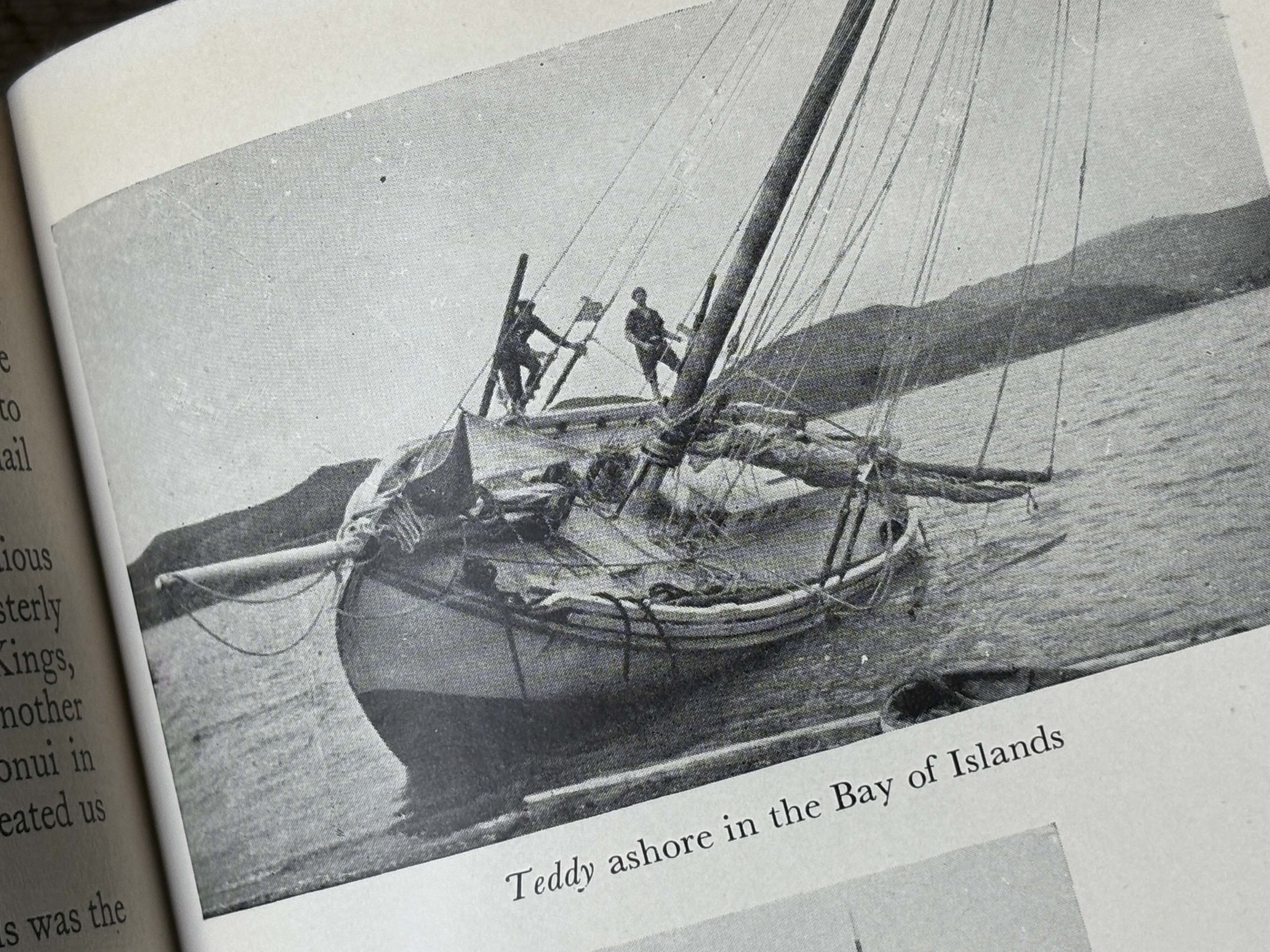

We struck the first time. I felt how the rocks crunched beneath our keel. TEDDY heeled over, hard, then, righting herself, was lifted again and carried onward, past the point, right into the breakers....

I shouted to my wife to fetch little Tui from out of her bunk in the cabin. The same instant TEDDY was seized by an enormous wave, lifted high, and with one big sweep thrown sideways against the rugged rocks. Then everything seemed to happen at the same time. Planks crushed, spars splintered. Rumbling-crashing-shrieking-rushing waters -and above it all the thundering roar of ten thousand unfettered demons of the waves.

Sometimes buried in foam so that we lost our breath, sometimes clinging to an almost perpendicular deck, when the sea was on the return, we needed all the presence of mind that we could muster. The main boom had come adrift. One of the topping lifts had jammed in a block sheave aloft, keeping the heavy spar suspended just over the cabin coamings and leaving it to sweep wildly from side to side, hardly twenty inches above the deck, whenever the boat rolled. The boom was like a huge club swung with deadly intent by a cunning giant hand.

To dodge its shattering blows, we were continually forced to flatten out on the foam-swept deck.

Tony in his canvas harness, tied by a short rope to the rail, was in immediate danger. I succeeded in undoing his rope and then, in that fraction of a second when the main boom hung still, while gathering momentum for another sweeping assault, I ventured to leap on to the rugged face of the rock. It was a desperate chance. For one terribly long moment I hung by one hand, with the other attempting to support Tony, whose grip around my neck was gradually loosening, while the rush of returning water seemed to load insufferable tons of weight on to us. The next moment I found a foothold and climbed on to the ledge, where I left Tony with strict orders to grab a hold and hang on. Then I returned to the boat.

Again and again the receding surf would drag the doomed boat away from the cliff, brutally tearing her trembling timbers over an uneven rocky bottom, bumping her, ripping her with jagged teeth and leaving her heeling to seaward with the lower part of a precipitous deck submerged in surging foam and the mainboom-end swinging insanely about in the milky whirlpool. Then the next wave would pick her up and dash her against the rocks with the full force of her own weight. Oh, how I suffered!

I had taken Tui from Julie and told the latter to jump ashore, as soon as a chance offered. With my wife ashore to receive the baby, our chances of saving her would be all the better, I judged.

My wife slipped, or jumped short, or was washed overboard, none of us knows exactly how it happened. I only knew that I saw Julie disappear in the seething foam between the boat and the rocks. I saw my wife being whirled about is the churning, roaring surf amid countless jagged spikes protruding from the rocks. At intervals I saw her head, a foot or an arm above the seething waters, now close to the cliff now away out. I saw her clinging to the rocks in a desperate attempt to climb up even while the next breaker came thundering in. I pointed seaward shouting for her to try to swim clear of the surf Then the breaker was upon her. I could do nothing until I had saved Tui. There was no place on the boat where I could leave the baby even for ten seconds without committing her to certain death. As it was, I had sufficient reason to fear that Tui would drown in my arms ere I could bring her ashore. But it is hard to see one's best friend fighting a desperate battle for life without being able to come to her assistance.

However, Julie had not been battered to death against the rocks. She came to the surface again and grabbed hold of the main sheet, but before I could tend her a helping hand, the boom ran out jerking tight the sheet and hurling my wife away.

Somehow I contrived to bring Tui ashore. Hurriedly I handed her to Tony, instructing him to look after her and not to leave her, no matter what happened. I then hastened to the rescue of my Julie.

But in the meantime she had achieved the seemingly impossible feat of swimming clear of the surging breakers. With infinite relief I saw her making for a large piece of floating timber on the sheltered side of the point, meantime using the broken sweep for a support. A motor launch I had not previously noticed had put out a dinghy to go to her assistance. She called out to me in a voice which showed that she was very much alive. Well, she had certainly proved her mettle.

Tony, too, had behaved like a hero. Without a word he had taken his duties like a man, sitting on the rocks where I had left him in charge of Tui. He never budged, even when the breakers washed over them occasionally. In all my misery, I could not help feeling proud of him.

Spare Provisions had also been washed overboard. I had seen the poor dog fighting in the surf, but could do nothing for her. However, she had saved herself, limping and bleeding she joined our line group of castaways.

The fishing launch brought us back to Kawau. When the family had been put up at the Mansion House, I returned to the wreck to see if anything could be salvaged. It proved impossible; the seas were continually sweeping over the hull, which was waterlogged and badly strained. Her flag, the proud ensign of the Royal Norwegian Yacht Club, awarded her for her merits, was still flying, half mast, where it had jammed is the rush of events. “As if TEDDY bemoaned her own end!” said one of the fishermen. I felt differently. To me it seemed as if my noble boat mourned not her own funeral but the end of a beautiful dream and the misfortune of the master who loved her.

I turned away. I had seen her dear and pretty lines for the last time.

When I returned on the following morning Teddy- my kingdom- had vanished.