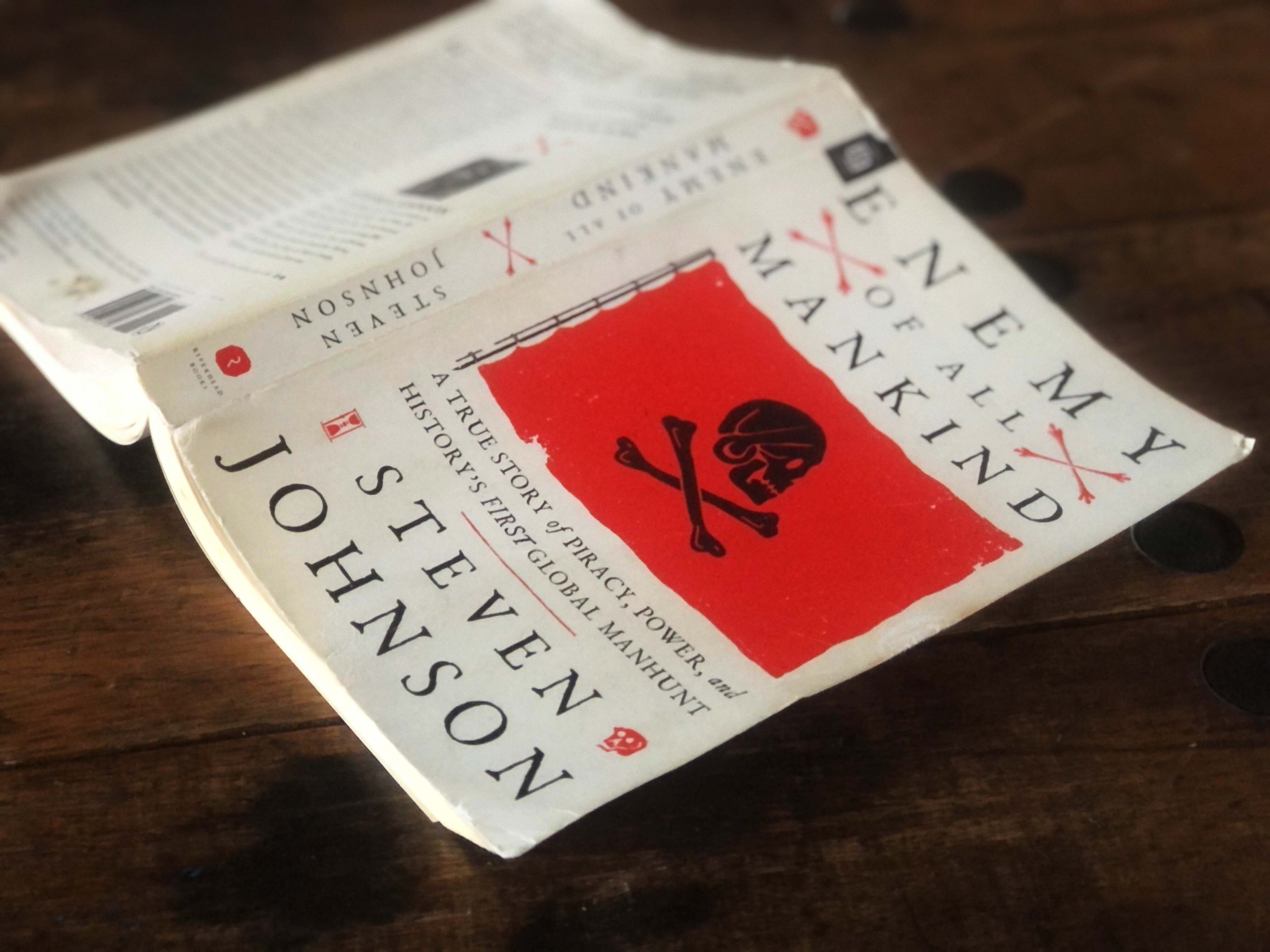

“The Enemy of All Mankind”

This book review by John Gapper was first published in the Financial Times in 2020

When the English pirate Henry Every seized treasures from the 1,500-ton GANJ-I-SAWAI (GUNSWAY), owned by India’s Grand Mughal Aurangzeb, off the coast of Surat in September 1695, it was the heist of the 17th century. It was also “one of those rare moments where multiple long arcs collide in spectacular fashion”, writes Steven Johnson. Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he? The polymath American journalist and popular historian is an old hand not only at retelling fascinating stories but also at wringing every last drop of significance from them. He did this in The Ghost Map (2006), his book about John Snow’s discovery of the cause of cholera in 1854, and now repeats the feat with “Enemy of All Mankind.”

English pirate Henry Every, notorious for the violent capture of the Indian treasure ship the GANJ-I-SAWAI in 1695 © Everett Collection

Johnson is a bit of an adventurer himself, sailing interdisciplinary seas to lay his hands on pieces of information wherever he can find them. But his material is genially attributed to its sources, and he has such a narrative gift that he deserves clemency. From the 17th-century craze for Indian calico to the speed at which the hulls of wooden ships rotted, it is all here. Curiously little is known about Henry Every, despite becoming the world’s most famous pirate, lauded by balladeers and pursued across oceans by the East India Company but never brought to justice. Reputedly born in the village of Newton Ferrers near Plymouth, he took up the romantic if hazardous life of a Devonshire pirate on his notoriously speedy ship, the FANCY. While eight of his crew were later hanged for mutiny, after a jury had obstinately cleared them of piracy in what was intended as a show trial in London, Every himself vanished. His character and motives are obscure, save for a brand-building letter he wrote in 1694, insisting, “I Have Never as Yett Wronged any English or Dutch, nor Never Intend while I am Commander.” Claiming to be “An Englishman’s Friend” was astute, for the line between pirates and privateers such as Sir Francis Drake, who boarded Spanish vessels with official sanction, was blurred. Steal foreign treasure out at sea, and the Crown might overlook your methods. “To be a pirate meant that you were simultaneously beneath contempt and on a thrilling road to respectability — even to knighthood.” It also resonated on the streets, where pirates became celebrities through the medium of song.

“French, Spaniard and Portuguese, the Heathen likewise

He has made a war with them until that he dies,”

ran one ballad celebrating Every. It was sung after he led a mutiny on a trading convoy financed by James Houblon, a member of parliament with ties to the East India Company.

Henry Every and servant

Aside from patriotism, pirates gained popularity for their democratic ethos. “Every man shall have an equal vote in affairs of the moment,” declared one pirate code. Their executive pay structure was much flatter than modern companies too, with the captain and the quartermaster (a kind of chief operating officer) receiving two shares of any spoils to one for each member of crew. A pirate’s life had drawbacks, including a high risk of disease in crammed cabins where viruses spread easily — social distancing was impossible on a 17th-century galleon. But when onshore wealth was held by aristocrats, and venture capital was being poured into global trade, the risk-reward ratio of being a high-seas raider was attractive.

The cannon shot from Every’s ship that broke the GUNSWAY’s mast was heard around the world. GANJ-I-SAWAI meant “exceeding treasure” in Persian, and Every’s pirates found gold, silver, jewels, ivory and saffron worth £20m at today’s prices, torturing the crew to locate it all. They also found dozens of women wearing hijabs, reputedly including one of Aurangzeb’s granddaughters, who were on a pilgrimage to Mecca from Persian-controlled India. Every was reported at the time to have married the granddaughter on the spot, “having found something more pleasing than jewels” — a version of history that is, as Johnson notes, “implausible at best”. The other GUNSWAY women were subjected to brutal mass rape, an act that “transgressed the most cherished of the Universe Conqueror’s possessions: his fortune, his faith and his women”.

The East India Company, facing expulsion from India amid outrage, turned its crisis into an opportunity by pledging to guard the seas against pirates. The trial was part of an official effort to maintain its foothold by punishing the pirates. As the lead prosecutor told the jury, Britain faced “the total loss of the Indian trade, and thereby, the impoverishment of this kingdom”. It was a crucial moment for Britain’s future empire, Johnson argues, drawing on Philip Stern’s book about the East India Company, The Company-State (2011). It turned into a naval force and later, at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, a conquering army. An English pirate’s violent robbery led the way to his country’s seizure of a continent.

John Gapper is editor-at-large of Nikkei Asian Review

“Enemy of All Mankind” should be purchased from a local bookshop such as this one